The Greatest Male Nudes in Art History (NSFW!)

Nudity started being an important subject in art in ancient Greece. The male body was celebrated at sports competitions or religious festivals, it...

Anuradha Sroha 19 November 2024

From Kylie to the Kardashians, bums seem to be big news. But that’s not modern selfie culture – the female body, especially buttocks have been a symbol of fertility and beauty since early human history and this is perfectly mirrored in art. As Meghan Trainor sings “it’s all about that bass.”

Modern women face a daily barrage of misogynist, hopelessly unattainable images of womanhood. It’s good to remember that womanly bodies come in all shapes and sizes, so let’s take a moment to celebrate that cellulite.

The Venus of Willendorf has exaggerated buttocks, hips, and thighs. Made of oolitic limestone, she is just over 11cm (just over 4 inches) tall and can be held in the hand. She is over 25,000 years old from the Paleolithic Period. Academics suspect she is a goddess/deity figure – a symbol of well-nourished fertility.

Modern excavations at the 4th century Piazza Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily revealed one of the richest collections of Roman mosaics in the world. This one above was found in the master bedroom!

Peter Paul Rubens is, of course, the undisputed master of the fleshy bottom. In The Judgement of Paris we see a kind of beauty contest between Venus, Juno and Minerva, the prize being the golden apple in his hand. These large, fleshy goddesses look confidently in command of their bodies and their sexuality.

Three equally confident beauties appear in Rubens’s The Three Graces. This skillful signature style earned him the term ‘Rubenesque’ for portrayals of realistic, sensual flesh. Rubens didn’t stick to the rigid female archetypes of so many male artists, and the playful, plump, dappled derrieres of his women are a joy to behold.

Rubens painted Venus in Front of the Mirror around 1613, an image re-visited by Diego Velazquez some 30 odd years later. Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus is more slender, with darker hair than the more rounded Rubens and without adornment. It is quite a departure from the classical depictions found in other works.

The Rokeby Venus is the only surviving nude by Velazquez. Nudes were rare in 17th century art – remember the Spanish Inquisition was policing the art scene! This painting is famous for being attacked by Suffragette Mary Richardson in 1914, but it was fully restored. She said she didn’t like “the way men visitors gaped at it all day long.”

The legacy of the Rokeby Venus is seen clearly in Manet’s Olympia. She doesn’t make it into our shortlist as she is sitting on her bottom, looking out at us. But suffice to say Manet’s stark portrayal of a ‘real’ woman caused a huge stir when it was released to a Parisienne audience.

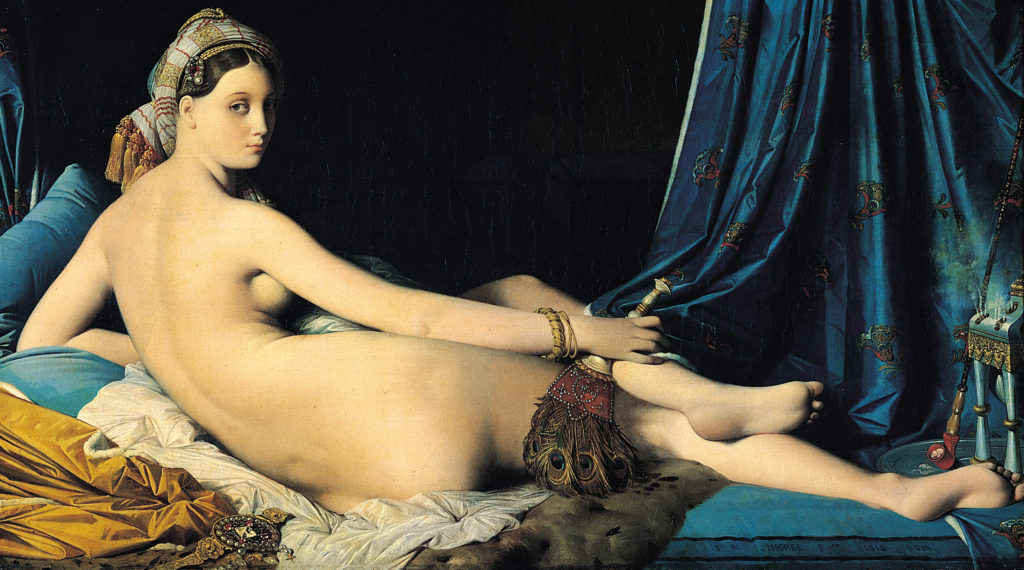

Another image that drew strong criticism was La Grande Odalisque, the most famous nude by painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in 1814. The long, sinuous lines of this woman bear little resemblance to anatomical reality, a distortion derided by contemporary critics. Now it is hailed as the first great nude of the modern tradition.

Moving away from traditional representation of the nude figure in painting, Paul Cezanne painted a whole series of bathers, singly or in groups from the 1870s onwards. His large The Bathers is considered one of his finest works and was an inspiration for the Cubist movement.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau stayed with the grand manners of the past when he orchestrated a whole host of frolicking nymphs in his painting The Nymphaeum in 1878. These are not really flesh-and-blood women – they are visions of perfection. They have impossibly smooth skins and perfectly proportioned bodies, but I have included it here, just for the sheer number of bottoms!

Pablo Picasso was the first to deconstruct the butt with Desmoiselles d’Avignon. See how the graceful curves of Rubens have become sharp and jagged. These women seem dangerous rather than welcoming, but this is still the male gaze we are dealing with here. Picasso was no feminist!

In the twentieth century, it seems we fell out of love with flesh. Or at least with the celebration of its gloriously feminine form. However, let’s end with South America’s Fernando Botero, whose women have a voluptuous glory that is marvelously celebratory. Enjoy!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!