Three paragraphs. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City introduces the exhibition Joan Miró: Birth of the World, with three paragraphs.

The first paragraph ends with the following sentence:

“…Miró’s intense engagement with poetry, the creative process, and material experimentation inspired him to paint The Birth of the World.”

The third paragraph says that MoMA:

“…situates The Birth of the World in relation to other works by the artist to shed new light on the development of his poetic process and pictorial universe…Collectively they testify to Miró’s ongoing quest to express ‘that moving poetry which exists in the most humble things.’”

Based on this introduction, I was hoping to learn more about the connection between Miró’s visual art and ‘that moving poetry.’

I struggled to find the connection, but no worries. This collection of Joan Miró’s paintings and sculptures is magnificent. I recommend it to anyone with even a remote interest in this great artist. The art is so wonderful, it does not need an interesting theme to warrant attention. As I walked through the exhibition and looked at painting after painting, I soon realized I was going to read very little about Miró’s ‘poetic process,’ but I didn’t care; I was able to cast my disappointment aside almost immediately.

In so doing, I freed myself from the shackles of a curator’s vision and experienced each work of art from my own perspective. The Birth of the World has always reminded me of Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World, painted decades later. Both paintings tell a story, even if the story is unknown to the viewer. The horizon line of both paintings, assuming a nonrepresentational painting is able to have a horizon line, is high, almost reaching the top of each canvas. The object that is the center of attention in the foreground is small and crisp. This is true for Christina, unable to rise to her feet. The viewer, along with Christina, looks ahead at the field of grass that seems to go on forever until one sees the shacks in the distance. Miro paints a small white circle in the foreground of his composition with a black straight form beneath it. With a small leap of faith, one can see a figure on her knees, unable to get up, looking at a seemingly unending expanse of nonrepresentational space. The viewer’s eye then travels to the black triangle and the small red circle to its right. Nonrepresentational space, whether it is off in the distance or merely higher up in a flattened space, can create the same mood as a representational space can create. Other than the three small objects described above, this world has vague shapes moving about, resembling black misty clouds with white light seeping in the middle of the canvas, leading to what?

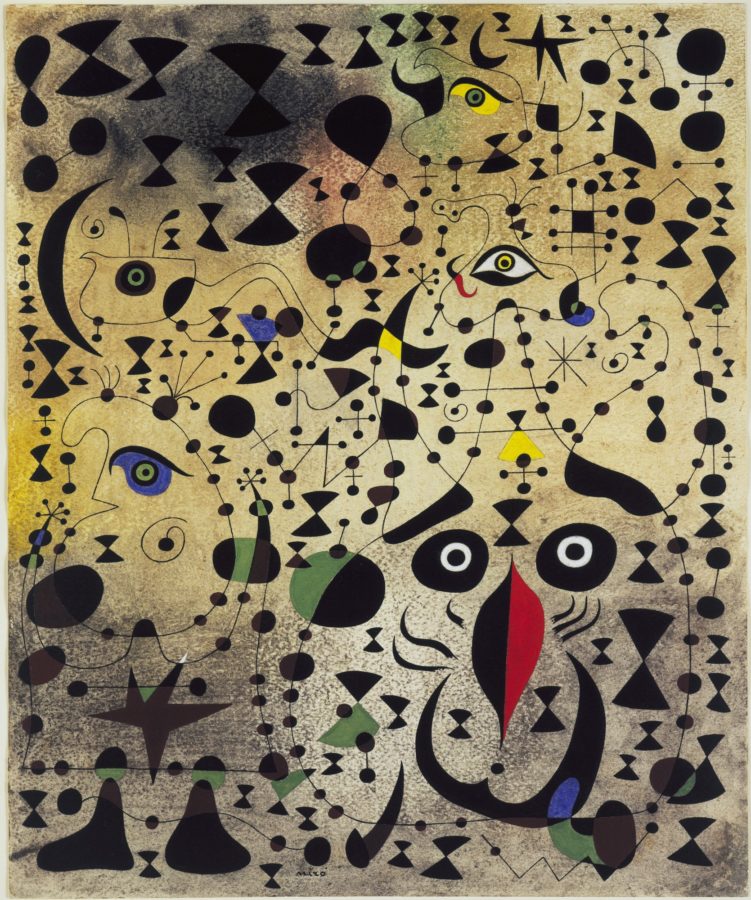

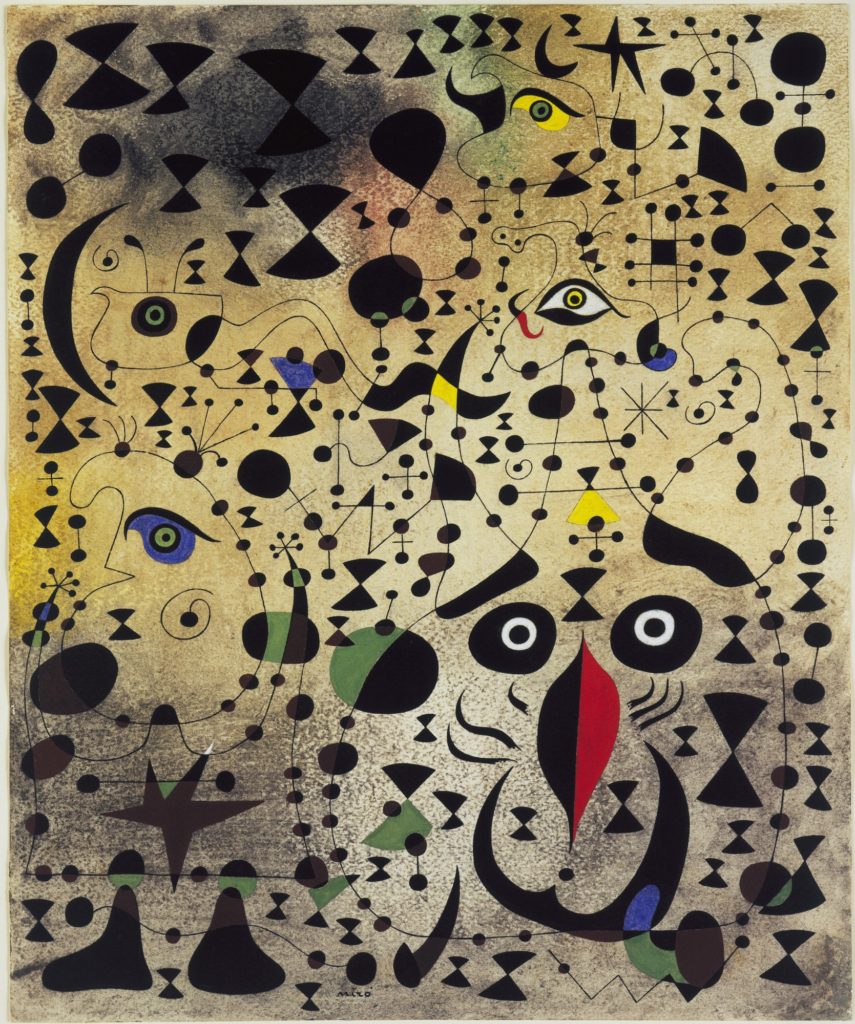

Miró’s compositions have the rare ability to work just as well when only part of the canvas is seen at one time. I noticed this while I was taking pictures of some of the paintings. One example of this phenomenon is Bather, from 1932. From a distance, the bright orange form of the bather turns yellow; the biomorphic shapes are opposed by the background that is white in one area and dark blue, orange’s complement, in another. However, cropped images of this painting have strong compositions in their own right. Many artists struggle with design, but with Miró, the final product shows no evidence of struggle. The Beautiful Bird Revealing the Unknown to a Pair of Lovers is another example. With this painting, the cropped images have a different mood from that of the full size painting. This is because the black shapes are larger in the cropped version; the organized harmony of what seems like hundreds of small crisp black forms dancing with one another in the full size painting is lost, but the beauty of the shapes is such that even when enlarged, they are strong enough to create a beautiful composition nonetheless.

MoMA’s description of The Family, from 1924, provides a glimpse into Miró’s thought process:

“‘I make no distinction between painting and poetry,’ asserted Miró. Adopting similar creative techniques to those of his poet friends, Miró developed a vocabulary of visual signs that could be compared to words. In drawing The Family, hieroglyphic forms symbolize a father, mother, and young child ‘glimpsed,’ as Miró described, ‘in the intimacy of their home.’ These imaginative characters are carefully placed within a faintly visible grid, in which the mother’s plant-like body acts as an anchor. The small flames extending from her heart, Miró indicated, stand for maternal love.”

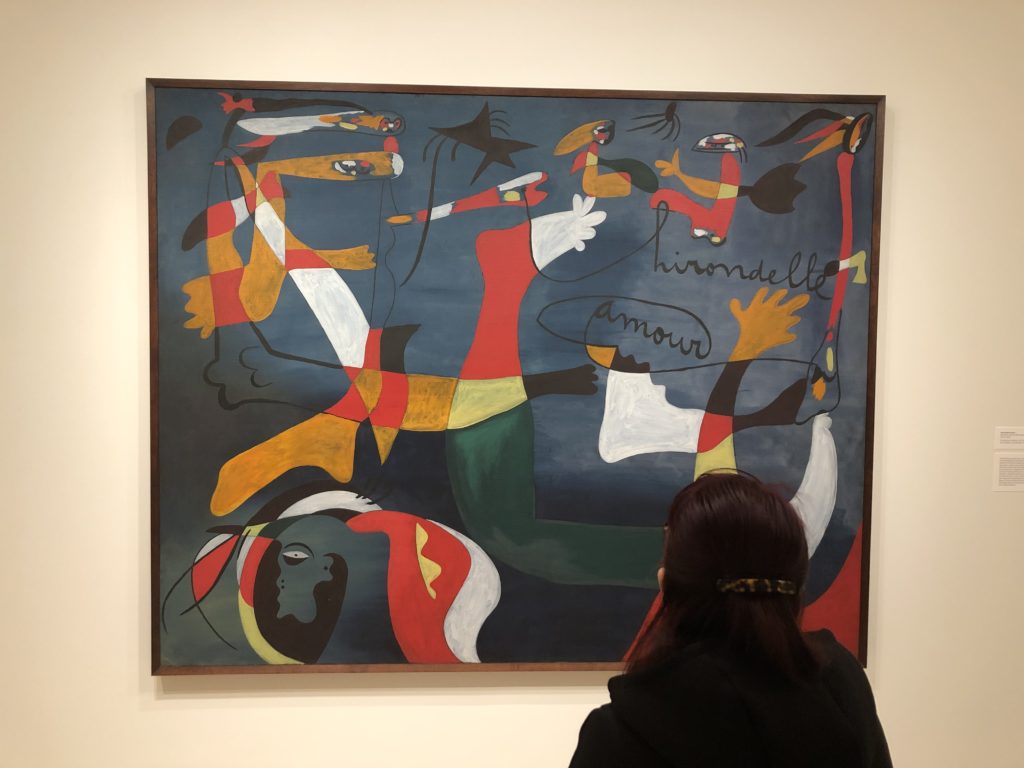

Another beautiful painting, Hirondelle Amour, from late fall 1933-winter 1934, is accompanied with the following description:

“This painting’s sinuous lines, exuberant forms, and interweaving of visual and verbal motifs epitomize the fluid exchange between painting and poetry in Miró’s work.”

However, MoMA needs to do more than make reference to Miro’s poetic vision. It needs to better articulate what that poetic vision is. Miro associated with many poets; I understand that. Is the connection based on Miro’s use of symbolism? Poets use similes and metaphors to describe a feeling or a person or an idea indirectly. Is Miro’s use of circles and triangles and other symbols poetic because his painted forms are one step removed from the objects they represent?

MoMA hints at the meaning of this exhibition with its description of the exhibition on its website.

“’You and all my writer friends have given me much help and improved my understanding of many things,’ Joan Miro told the French poet Michel Leiris in the summer of 1924, writing from his family’s farm in Montroig, a small village nestled between the mountains and the sea of his native Catalonia. The next year, Miro’s intense engagement with poetry, the creative process, and material experimentation inspired him to paint The Birth of the World.

“In this signature work, Miro covered the ground of the oversize canvas by applying paint in an astonishing variety of ways that recall poetic chance procedures. He then added a series of pictographic signs that seem less painted than drawn, transforming the broken syntax, constellated space, and dreamlike imagery of avant-garde poetry into a radiantly imaginative and highly inventive form of painting.”

This description provides more of a clue about the poetry-painting connection than anything else in the exhibition. Even with this, I want to go deeper. On the same page as the above quote is a short video that has a poem written by Jacques Prevert, a longtime friend. There is a mirror in the name Miro, Prevert writes. Prevert tells us about “dragging the cloak of morning along behind” and “the black sun collapses into the cellar of dusk.” These are beautiful images.

Maybe in my quest to explore the answer to the question inspired by this exhibition, I am able to arrive at a sense of understanding after all. Maybe my initial critique of this exhibition was the first of many steps I needed to take first. By the way, MoMA does a beautiful job of presenting the artwork. I highly recommend this exhibition, especially for those of us who wish to immerse ourselves in the art of one of most prominent artists of the twentieth century.

Joan Miro: Birth of the World is on view until June 15, 2019.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0870707256″ locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/51h4ks5Eu8L.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”82″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”3836529238″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/41xwO7DSk2BL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”91″]