Summary

Florine Stettheimer, an American artist, was celebrated in her time but has been overlooked since. A recent biography debunks myths about her life and work.

Florine Stettheimer’s Unique Style

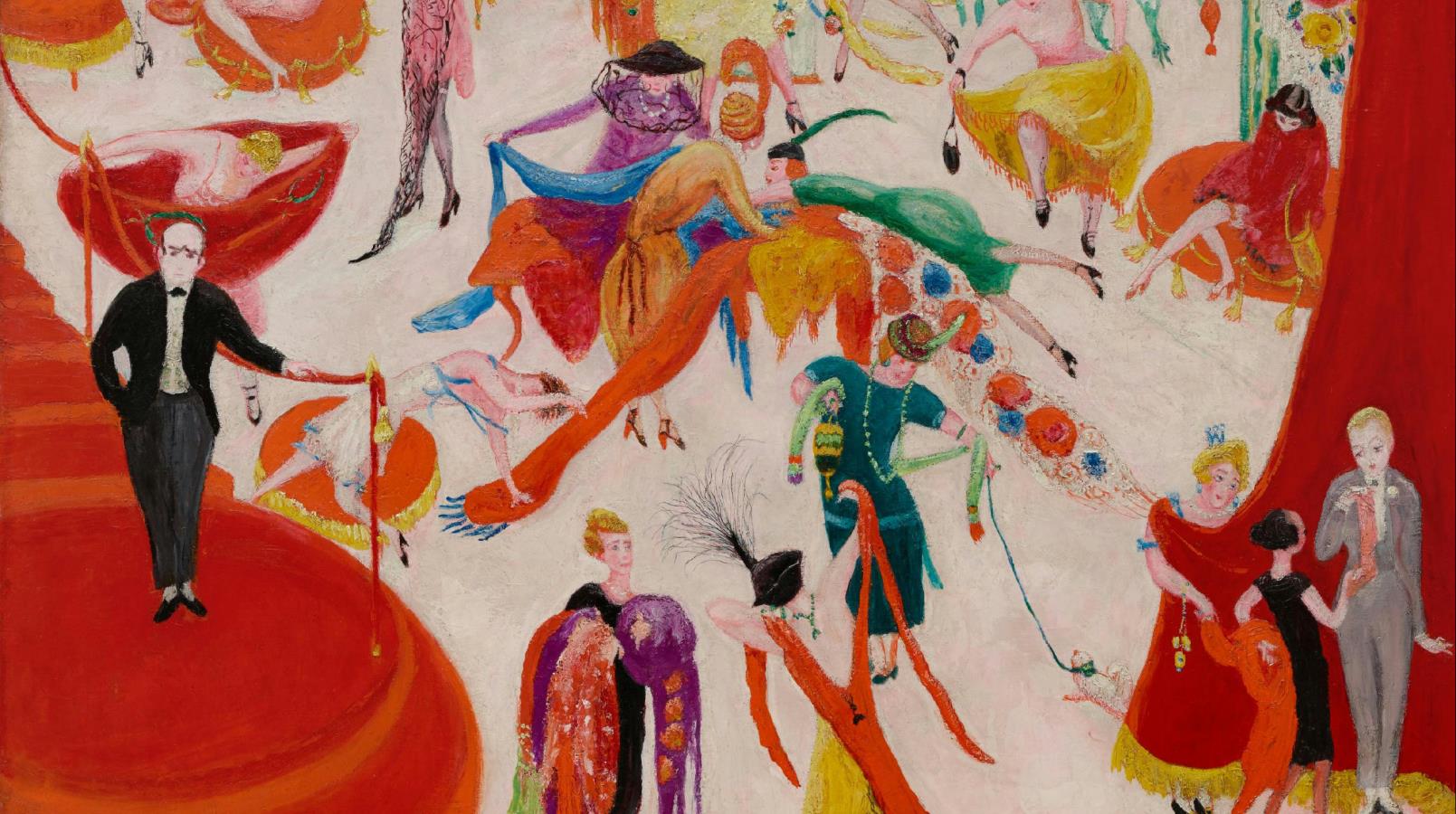

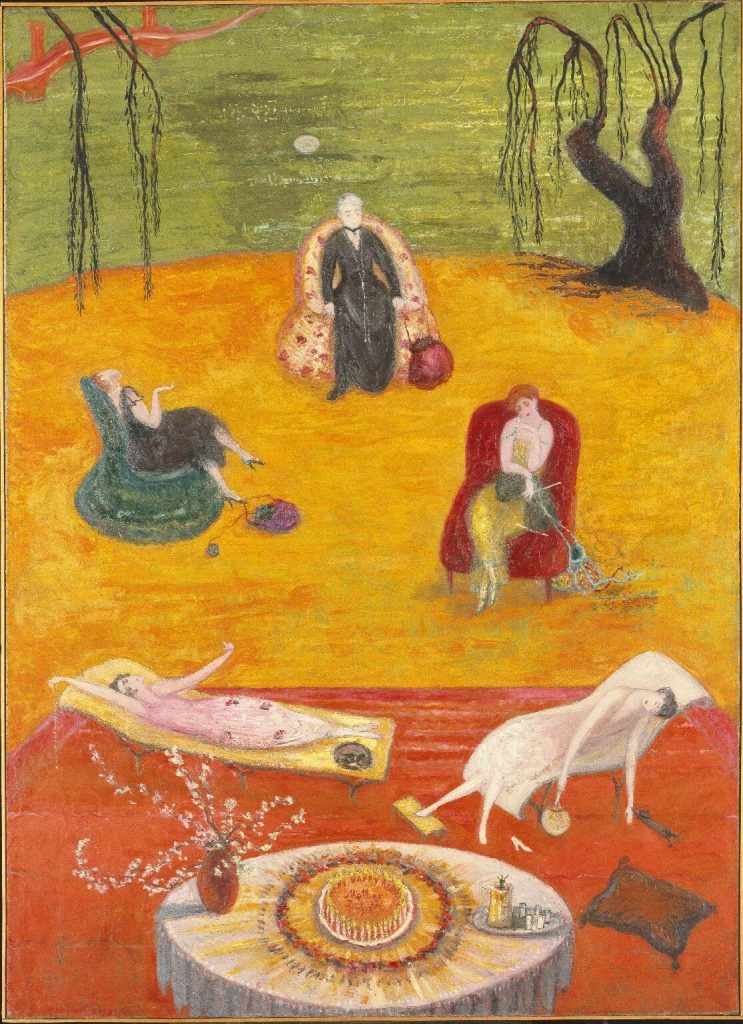

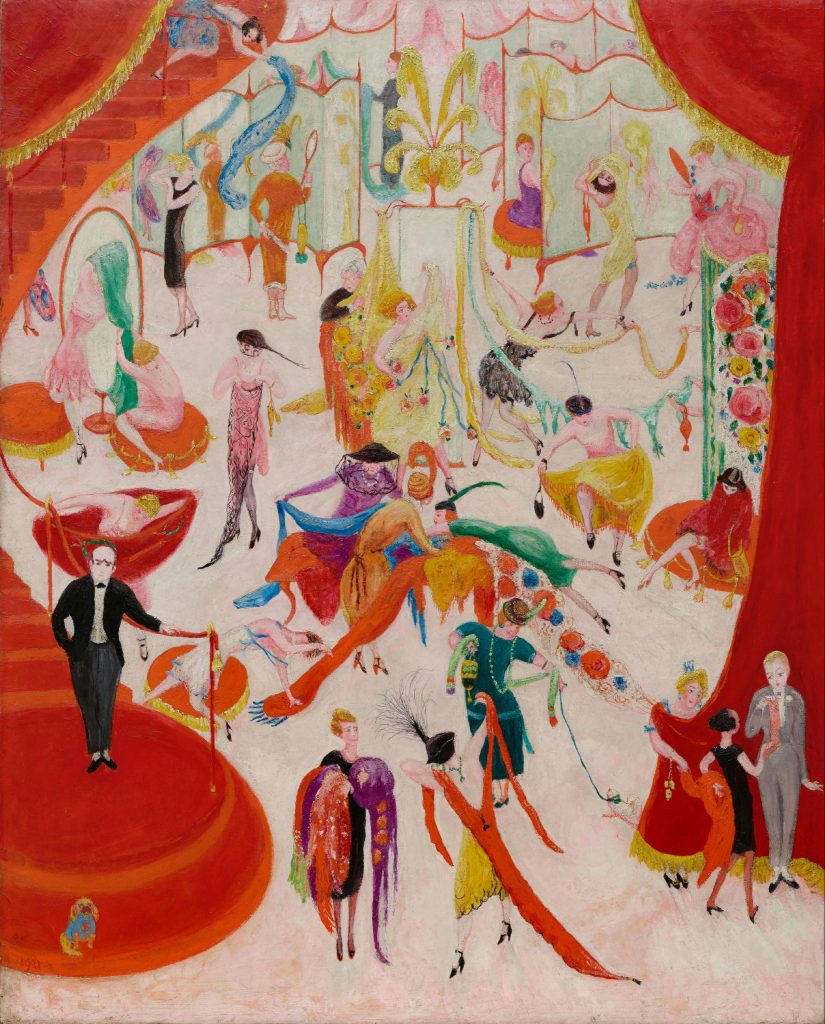

Stettheimer’s whimsical, lanky figures and their exaggerated poses make her paintings easy to identify. They remind me of the comical figures painted into the margins of medieval manuscripts because of their lengthened proportions and unusual postures.

Rendered in bright colors, her works use busy, intentionally distorted compositions that condense space and time to include multiple places and events on the same canvas. Inspired by Rococo Revival, 20th-century mass media, and New York City, her paintings are elegant and kitschy in equal measures. She frequently included words as key features of her images and signed them in whimsical places. It can be fun to hunt around to spot her signature.

Florine Stettheimer, Heat, 1919, Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Naive on Purpose

Despite her folk art-esque style, Stettheimer was far from untutored. The daughter of wealthy Jewish parents, she studied art in Europe, where she lived with her family until the start of World War I, and at the Art Students’ League in New York. As her early works demonstrate, the naive style of her mature career was her choice, not her skill level. She was also well versed in historical and modern European art and payed homage to both Manet’s Olympia and Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in her work.

Teasing About Modern Life

Florine Stettheimer, Studio Party (Soirée), c. 1917-1919, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

Stettheimer’s subject matter most often centered around her two social circles — upper-class Manhattan and avant-garde salon society. Along with mother, Rosetta, and sisters Carrie and Etta, she made artistic and literary friends like Marcel Duchamp and Carl van Vechten.

The Stettheimers hosted salons and parties for their rarefied circle in their city and summer residences. Like many of her great artistic predecessors, the artist included her own likeness in dozens of her paintings, where her trademark red stilettos distinguish her. Her family and close friends made frequent cameos as well. A flaneur-type observer of society, Stettheimer’s inclusion of her own image in so many of her paintings has sometimes been interpreted as acknowledgement of her own participation in the social pageantry she satirized. She clearly had no problem with a little self-flattery, as she portrayed herself at the same youthful age throughout her entire life.

More Than Meets the Eye

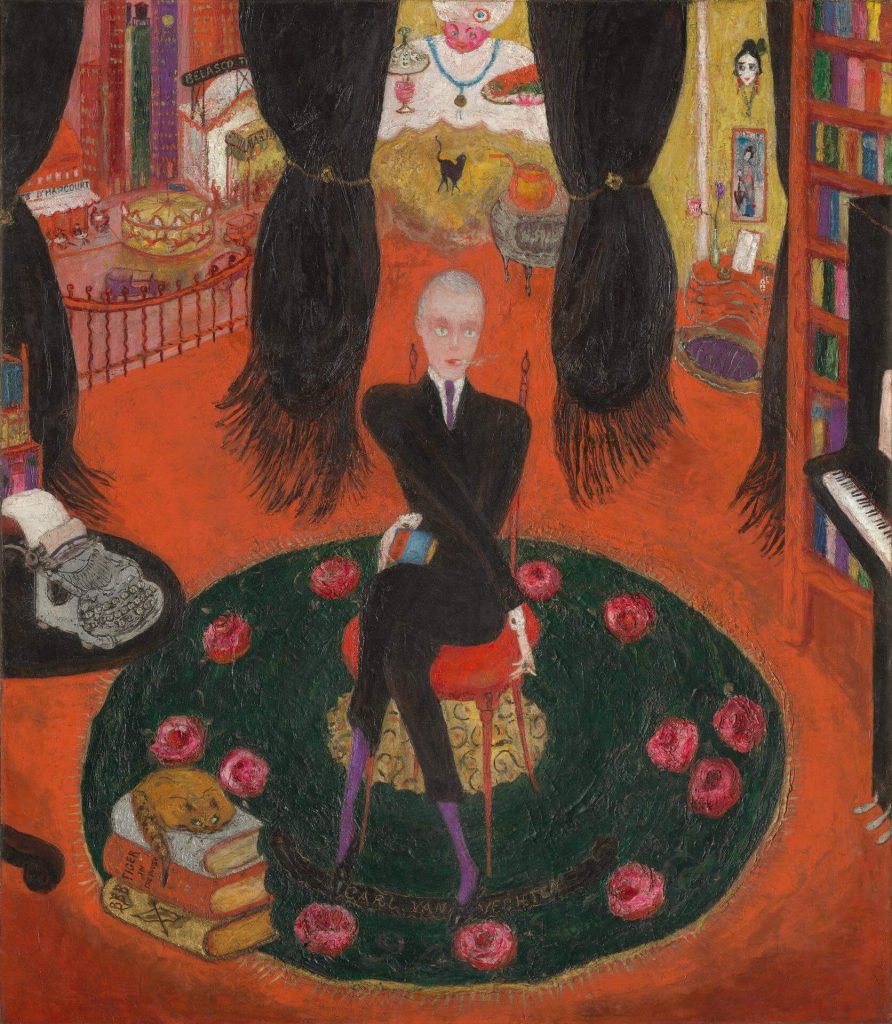

Florine Stettheimer, Carl van Vechten (1880-1964), 1922, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

On the surface, Stettheimer’s paintings of birthday parties, days at the beach, and beauty contests gently parody the charades, habits, and preoccupations of her time and place. However, her exuberant tone and idiosyncratic style distract from her deeper, more insightful commentary. Stettheimer never overtly addressed social or political issues in her painting but instead included subtle hints of topics such as sexism, racism, LGBTQ+ issues, and antisemitism. You can only find them if you know what to look for, and they may have been lost on some of her contemporaries.

For example, her portraits of several gay friends include coded references to their homosexuality, like the red tie and purple socks in Portrait of Carl van Vechten. Titling a painting of the Jewish Stettheimer family and their Jewish and Catholic friends enjoying the beach, Lake Placid was another subtle comment, as the Adirondack resort was notoriously intolerant at the time.

She visited the African American side of the segregated beach at Asbury Park, New Jersey, and painted the beach-goers with all the same individuality and celebration she did her white subjects. The list of such gentle commentary in her work could go on and on.

Paintings like her Nude Self-Portrait have also led some people to consider Stettheimer a pioneer of the “female gaze“, seeing her paintings as some of the first to truly depict both male and female forms from a woman’s perspective (and sometimes for a woman’s enjoyment). Complicating the matter, she painted another scene (Studio Party, Soirée, shown above) of both men and women looking at her nude self portrait.

Florine Stettheimer’s Greatest Hits

Florine Stettheimer, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921, Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer, 1951, 1951-27-1, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Stettheimer’s most famous works are the four paintings in the Cathedrals series now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They are The Cathedrals of Broadway (1929), The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (1931), The Cathedrals of Wall Street (1939), and The Cathedrals of Art (1942). In her characteristic manner of collaging together people, places, and ideas (something literally spelled out in words), these large canvases simultaneously celebrate and parody four major components of 20th-century Manhattan – entertainment, commerce, finance, and art. Artist Joan Snyder rightly described them as showing Stettheimer’s “cinematic sensibility”.

However, my favorite Florine Stettheimer painting is Spring Sale at Bendel’s, a scene of comic pandemonium at a New York City department store. The weightless and graceful figures give an elegant, choreographed feeling to the chaos of the scene. I wonder what Stettheimer would think of a 21st-century Black Friday sale.

I also enjoy her series of thickly painted flower paintings called “eyegays” (nosegays for the eyes). She made one each year on her birthday, based on a bouquet she had personally picked and arranged for herself.

Poetry and Design

In addition to painting, Stettheimer also practiced interior design and wrote poetry. Her delightful, clever, often snarky poems were meant for private enjoyment, but her sister Ettie published them under the title Crystal Flowers after Florine’s death. Surviving photographs of her various homes and studios are all that now remain of her furniture and interior design skills; they record a campy aesthetic that embraced lace and cellophane in equal parts. In the 1930s, she designed the sets and costumes for Four Saints in Three Acts, an avant-garde opera featuring a libretto by Gertrude Stein and score by Virgil Thomson.

Debunking Stettheimer Myths

Florine Stettheimer, Bowl of Tulips, 20th century, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

In her new book, Bloemink debunks the ubiquitous myth that Florine Stettheimer did not participate in traditional art exhibitions. It is certainly correct that she only had one solo exhibition in her lifetime and declined numerous subsequent offers for such shows. However, she participated in tons of group exhibitions throughout her career; Bloemink lists 45 in the back of the book. These included annual exhibitions at the Society of Independent Artists, the first Whitney Biennial, three MoMA exhibitions, and several shows abroad.

On most occasions, she appeared alongside the most celebrated artists of the day. This revelation and several others in the book disagree with everything previously written about Stettheimer, yet they seem thoroughly backed-up by documentary evidence.

It is true, however, that she did not sell her work. Despite taking her art career very seriously, her wealth meant that she didn’t need to actually sell art to support herself. She preferred to keep her creations close by, asking inflated prices for her works when they appeared in gallery exhibitions to discourage potential buyers. After her death, her sister Ettie distributed them to major art museums across the country, according to Florine’s wishes.1 Columbia University got the bulk of the deal.

Reclaiming Florine Stettheimer’s Reputation

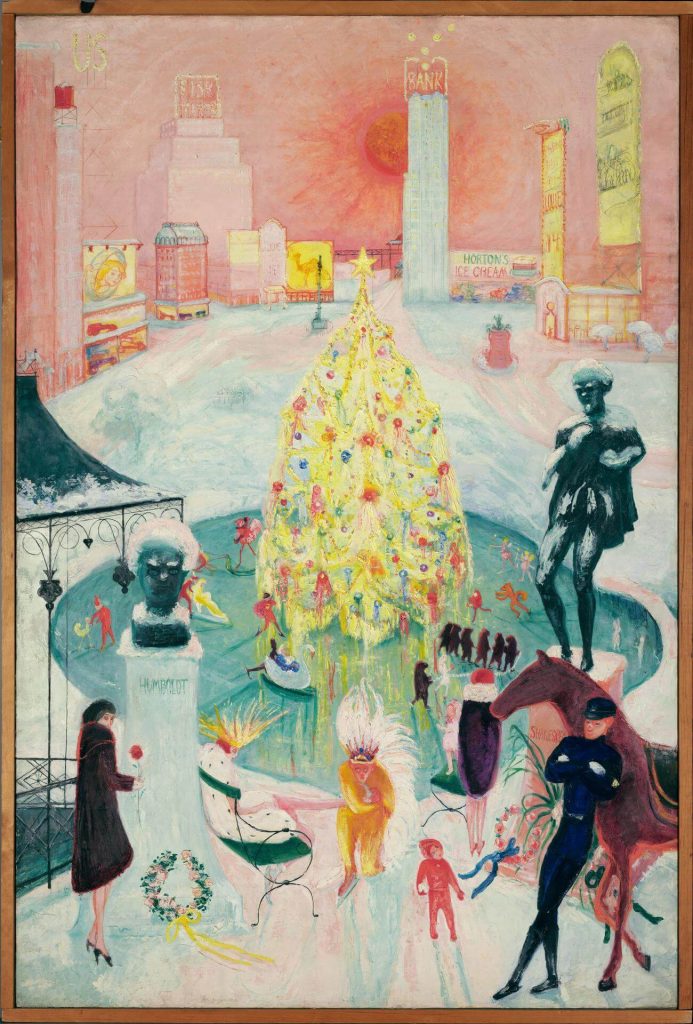

Florine Stettheimer, Christmas, c. 1930-1940, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

By Bloemink’s account, Stettheimer enjoyed great respect from her fellow artists. Her good friend Duchamp even curated her 1946 retrospective exhibition held at MoMA after her death.

The biography includes numerous references to artists and curators begging her to lend a work to an upcoming exhibition, claiming that no show of great modern art would be complete without her participation. Hyperbole aside, Stettheimer clearly held a position of great esteem during her lifetime. If she’s been overlooked and misinterpreted in the nearly 80 years since her death, and if her works have been relegated to museum storage and called frivolous or insignificant, the fault belongs to later generations. Her contemporaries understood and appreciated her just fine.

There’s no question that Florine Stettheimer was an individual. She clearly had her own point of view and wasn’t afraid to slyly express it. She was clever and quirky, and I think that’s what attracts so many people to her paintings. As interest in Stettheimer’s art has slowly returned over the past few decades, people have finally started to understand that she wasn’t a batty old lady, but rather an intelligent and sophisticated woman. She commented on the important issues of her day while keeping things light and joyful. And her art is a heck of a lot of fun!