Canine Companions: Famous Artists and Their Beloved Dogs

There’s nothing like the bond between a passionate creator and their loyal four-legged friend. Let’s explore the heartwarming...

Jimena Aullet 10 February 2025

The idea of birds in art probably brings to mind John James Audubon, the 19th-century ornithologist who wrote and illustrated the landmark series The Birds of America. However, Audubon was far from the only person to ever portray birds in art. From ancient history to the present day, birds have appeared in paintings, prints, metalwork, ceramics, and even entire rooms.

Martin Johnson Heade, Cattleya Orchid and Three Hummingbirds, 1871, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Small, vivid paintings of hummingbirds flitting among tropical flowers are the calling card of American artist Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904). Heade was friends with the great American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church but chose to do something rather different with his artistic career. Like Church, he traveled in the tropics, particularly Brazil, and fell in love with the natural scenery there. However, he chose to focus on the small-scale, rather than the monumental like Church. Heade’s works are equal parts exotic landscape painting and still life, though he also painted Hudson River School-style landscapes. Later in his life he moved to Florida and painted the natural scenery there.

Martin Johnson Heade, Two Hummingbirds above a White Orchid, c. 1875-1890, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA.

Heade loved hummingbirds, and who can blame him? He painted them over and over again, often in combination with orchids and other tropical flowers. During his 1863-4 visit to Brazil, he created a series of 16 works with the fitting title The Gems of Brazil; 15 of them depict hummingbirds.

Supposedly he painted all the birds from life. This is certainly a more humane practice than killing and stuffing them, as some other artists did. However, anybody who has ever seen a hummingbird in real life will know that they flap their wings so fast as to appear blurry to the naked eye. In a time before high-def cameras with quick shutter speeds, it’s a wonder that Heade managed to capture his hummingbirds in so much detail.

Several images from The Gems of Brazil were eventually made into chromolithographic reproductions, though Heade’s plans for an Audubon-style book never came to pass. He just continued on painting more hummingbirds instead. His original paintings for the series, along with the notes for his abandoned book, now live at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, 1876-1877, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Photo by Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

These peacocks are so fabulous that they have an entire room dedicated to them! The Peacock Room is a full-room work of art by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who characteristically titled it Harmony in Blue and Gold. He designed and executed it for the English industrialist Frederick R. Leyland, for whom it was both a dining room and showcase for his collection of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. Several of the dark blue walls are decorated with magnificent gold peacocks, painted in a style inspired by Asian art. Even the ceiling and shutters have decorative motifs reminiscent of a peacock’s plumage. The room epitomizes the sophistication of the Aesthetic movement at its finest. It also includes an easel painting by Whistler, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, depicting a young woman in Japanese-style clothing and setting.

Despite the glory of the Peacock Room, Leyland was apparently not a happy customer. He sold the entire room to the American collector Charles Lang Freer in 1904. Freer had it disassembled, packed up, and shipped to his home in Detroit, Michigan for re-installation. He used it to display his own, more diverse collection of porcelain from all over Asia. Freer gave the Peacock Room to his eponymous Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (now part of the Smithsonian) when it opened in 1923. This necessitated another de-installation and transplant of the room.

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, 1876-1877, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Photo by Slowking via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0). Detail.

There are three possible ways to display the Peacock Room – without any porcelain, with Chinese blue-and-white porcelain as Leyland had it, and with Freer’s assorted Asian porcelain. Each arrangement reveals different details of the decoration on the walls, ceiling, shelves, shutters, wood paneling, and trim. In 2011, curators compared old, black-and-white photographs to Freer’s porcelain collection in museum storage to identify each piece and put it back in exactly the same place Freer had displayed it. This short video explains the painstaking process and satisfying results.

Terracotta skyphos (deep drinking cup), mid-5th century BCE, Greece, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Depicting birds in art is a truly ancient tradition. The ancient Greek goddess Athena – Minerva, in the Roman tradition – had an owl as her symbol. Athena was the goddess of wisdom, so it’s no coincidence that the owl has become associated with that trait as well. This explains why the owl appears all over ancient Greek art and is particularly abundant in painted pottery. Judging by the example above, ancient vase painters seem to have realized the expressive potential of owls’ enormous eyes just as well as we do in the present day.

Tetradrachm with the Head of Athena (obverse) and an Owl (reverse), Athens, 449–393 BCE, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA. Photo by the author.

Athena’s owls also appear on metal objects like coins and statues, either alongside Athena or separately. This tiny silver coin from Athens, Greece – Athena’s city, of course – depicted Athena on one side and her avian representative on the other.

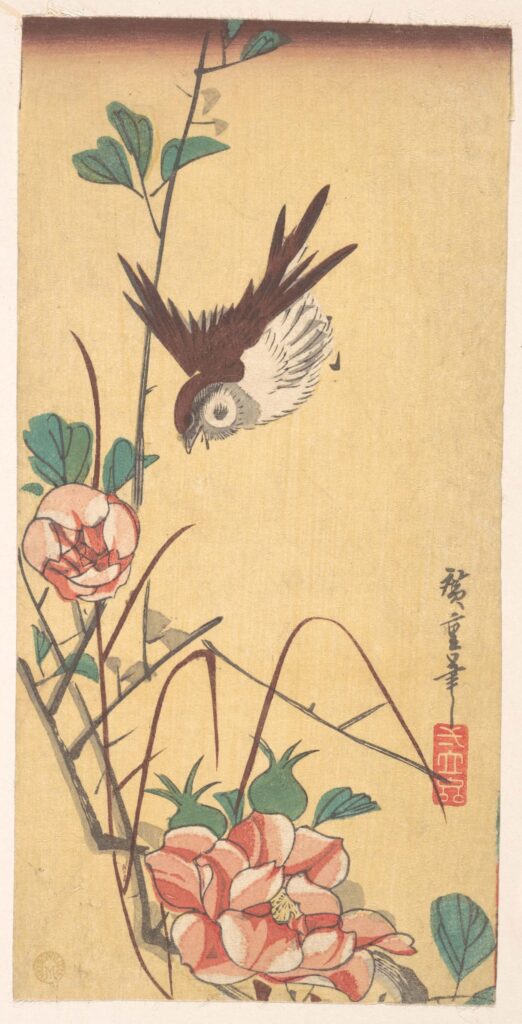

Utagawa Hiroshige, Roses and Sparrow, c. 1833, woodblock print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

In Japanese and Chinese printmaking, bird and flower prints found great popularity. Called kacho-e in Japan, it is an entire genre subdivided according to what sort of flowers are involved. Such images represent the changing of the seasons but also relate to spirituality, with the bird representing the soul. Flowers and birds in Japanese art can appear in subtle, monochrome prints or long hanging scrolls like this cheerful sparrow diving towards a rose shown above. They may utilize various styles and degrees of naturalism.

Although kacho-e is separate from ukiyo-e, the “floating world” genre better known to the western world, many of the same artists practiced both. These include Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), the author of this particular print above, and the great Hokusai (1760–1849). Kacho-e has ancient roots, but like ukiyo-e, it flourished during the Edo period (1615-1868). The image of sparrows and dandelions below, by Hokusai’s student Teisai Hokuba (1771–1844), was a privately-printed image known as a surimono, which was commissioned by a group of poets. Hokuba’s style differs quite a bit from Hiroshige’s.

Teisei Hokuba, Spring Rain Collection (Harusame shū), vol. 3: Sparrows and Dandelions, ca. 1820, woodblock print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Vessel in the Shape of a Bird, 100 BCE/500 CE, Moche, Trujillo, north coast, Peru, ceramic and pigment, Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

The Moche was a set of related cultures that flourished in Peru during the first millennium CE. Art lovers particularly celebrate them for their prolific pottery tradition. The Moche used molds to create pottery vessels, often in complex shapes, which they colored with red and cream slip. Much Moche pottery has distinctive “stirrups” – curving handles from which the spouts emerge. This pottery often takes on the fully three-dimensional forms of people and animals, including – you guessed it – birds. They may appear in naturalistic form, as in the unidentified bird above. However, they sometimes take on anthropomorphic qualities instead, like the fabulous owl pretender shown below.

Vessel in the Form of an Owl Impersonator, 100 BCE/500 CE, Moche, North coast, Peru, ceramic and pigment, Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!