Blood in (and as) Art

One of the first known expressions of human creativity, the Lascaux cave paintings, were created with blood, a material that has remained significant...

Kaena Daeppen 10 June 2024

Art history is painted with shades of prohibition—works banned, artists silenced, and masterpieces under attack. From centuries past to the cutting edge of today, the canvas bears witness to tales of censorship. Join us on a whirlwind tour through some of these stories from the last sixty years and discover a museum boldly showcasing a collection of forbidden art.

The beauty of art lies in its inherent permeability. Artists possess a unique gift—they can delve into nearly any discipline or issue, often taking on the role of activists like the feminist-activist art collective Pussy Riot. Yet, the effectiveness of any disruptive act is often met with a response in kind. It’s this very dynamic that transforms these pieces into potent subversive devices, challenging the status quo with artistic fervor.

Pussy Riot at Lobnoye Mesto on Red Square in Moscow, Photograph by Denis Bochkarev via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

From censorship driven by political or religious ideologies to artworks labeled as pornographic, the repercussions of actions taken against them stand as stark examples of threats to freedom of expression. It may seem surprising, but addressing censorship in art remains a pressing and contemporary issue, and the pieces that will be introduced shortly have been entangled in cultural wars, sparking media controversies.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio is a powerful exploration and celebration of the male homosexual sadomasochistic subculture. The portfolio’s thirteen meticulously composed images challenged societal norms and showcased Mapplethorpe’s transition to a more mature style. However, this series became a central point of controversy during the artist’s retrospective exhibition in 1989, The Perfect Moment, against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis and Mapplethorpe’s death from the disease. As a result, the show faced intense censorship. The Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled the exhibition in Washington, D.C., and the next venue in Cincinnati experienced police raids and obscenity charges. This controversy became a focal point of America’s “culture wars,” creating intense debates on freedom of expression and government funding for the arts.

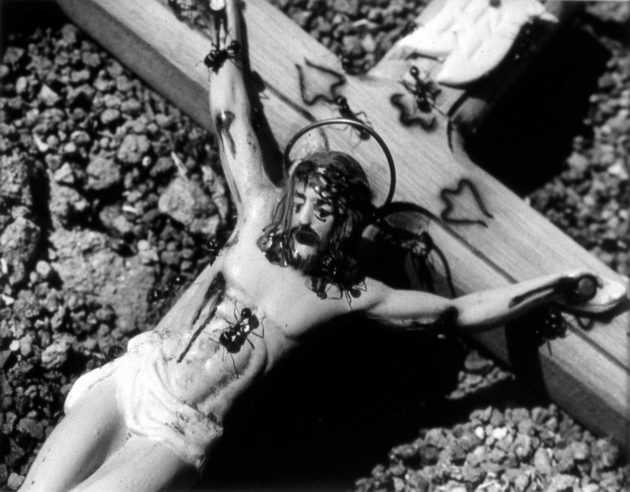

Andrés Serrano, Piss Christ, 1987, Museu de l’Art Prohibit, Barcelona, Spain.

Piss Christ captivates with an air of mystery featuring an image that initially conceals one of the most widely reproduced Christian iconographic images. Yet, simultaneously, it unfolds as distinctly disquieting upon closer inspection. Andrés Serrano is known for his provocative use of human corpses and bodily fluids in art. Certainly, this is his most controversial piece: a photograph featuring a crucifix submerged in a glass container of what was claimed to be the artist’s urine. Even if Piss Christ was a piece winner of an award partly sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts, it also ignited the late 1980s and 1990s culture wars, drawing criticism for its perceived blasphemy. The controversy reached its peak when the work was exhibited in 1989, with senators denouncing the government funding, leading to death threats, hate mail, and a cut in the NEA’s budget.

Despite facing vandalism and opposition, Piss Christ endured, symbolizing the ongoing debate on artistic freedom, freedom of speech, and the boundaries between art and sacrilege. In a surprising turn of events in 2023, Serrano was invited to meet with Pope Francis in the Sistine Chapel. Furthermore, the pope blessed him and acknowledged his Christian artistic expression, signaling a shift in perception from controversy to acceptance.

The crucifix is a symbol that has lost its true meaning—the horror of what occurred. It represents the crucifixion of a man who was tortured, humiliated, and left to die on a cross for several hours. In that time, Christ not only bled to death, he probably saw all his bodily functions and fluids come out of him. So if Piss Christ upsets people, maybe this is because it is bringing the symbol closer to its original meaning.

Interview With Andres Serrano by Jun 4, 2014, Last Updated Dec 6, 2017.

Another artwork that faced censorship for religious reasons was A Fire In My Belly, a video attributed to artist David Wojnarowicz. To clarify, the piece is a 4.16 minute film which was never finished as that. This version was specifically created for the exhibition Hide/Seek in 2010 at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC by its curator Jonathan David Katz and the artist Bart Everly.

The video contained a controversial 11-second segment recorded by Wojnarowicz in 1986 during a trip to Mexico which contains ants crawling over a crucifix. This specific footage raised questions about artistic interpretation, curatorial intentions, and, regrettably, the challenges faced by the collective in confronting the AIDS crisis.

Animals allow us to view certain things that we wouldn’t allow ourselves to see in regard to human activity. In the Mexican photographs with the coins and the clock and the gun and the Christ figure and all that, I used the ants as a metaphor for society because the social structure of the ant world is parallel to ours.

Interview with David Wojnarowicz in 1989

The controversy began when criticism from conservative groups, notably the Christian News Service, led to political condemnation and calls for removal. The Catholic League, politicians, and media pressured the Smithsonian, resulting in the film’s removal by Secretary G. Wayne Clough. As a result, the Association of Art Museum Directors criticized the Smithsonian, and arrests occurred during protests. Despite not being reinstated at the National Portrait Gallery, the film returned to future exhibits. The Warhol Foundation withdrew funding for the Smithsonian, prompting reflections on handling the controversy.

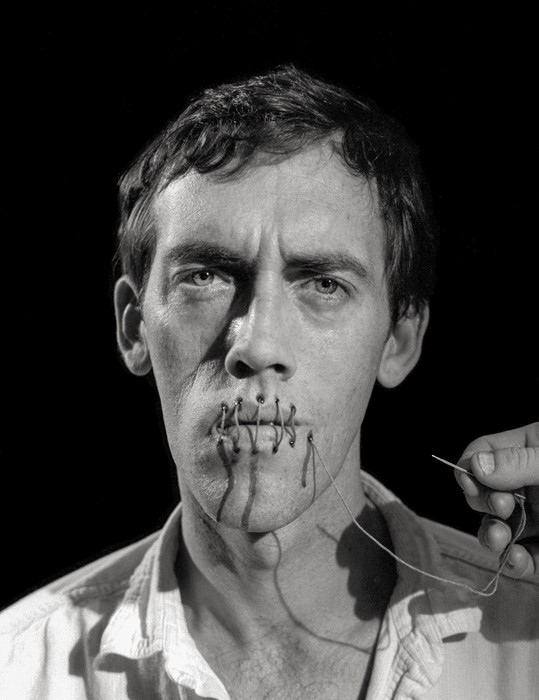

Andreas Sterzing, David Wojnarowicz (Silence=Death), 1989/2014, Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 2020. © Andreas Sterzing.

David Wojnarowicz’s body of work stands as a powerful testament to the artist’s unwavering commitment to freedom of artistic expression. As a multifaceted creative force, Wojnarowicz fearlessly intertwined personal narratives, his battle with AIDS, and fervent political activism in his art. Interestingly, Wojnarowicz not only faced censorship during his lifetime but also addressed it directly in pieces like David Wojnarowicz (Silence = Death), photographed by Andreas Sterzing, and the fact that his work has been censored in the last 15 years attests to how it remains strikingly relevant today.

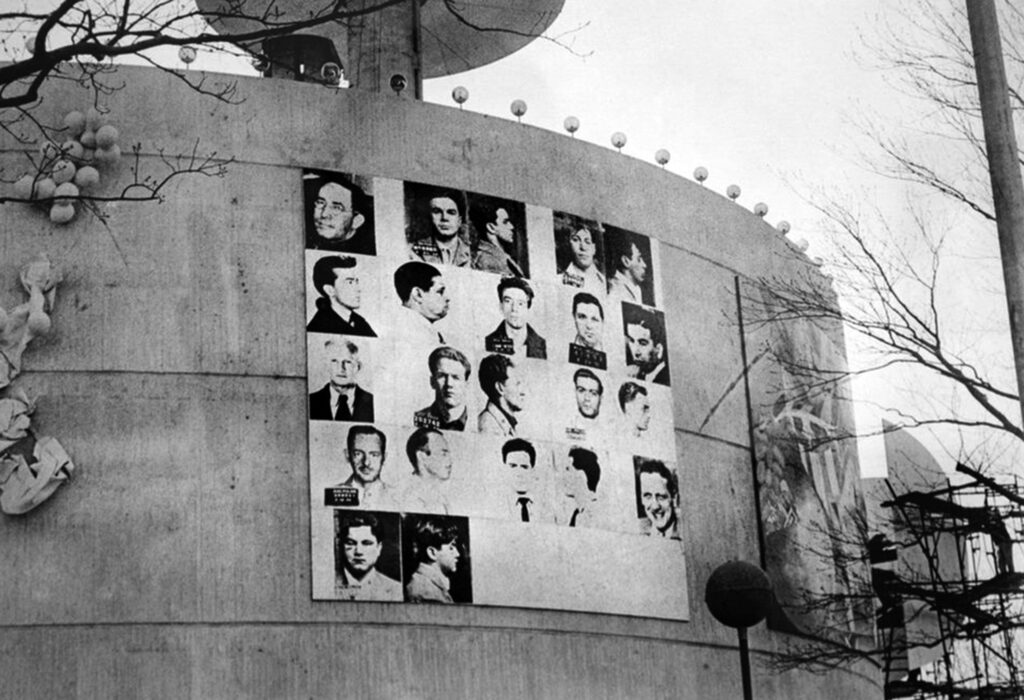

Andy Warhol, Thirteen Most Wanted Men, 1964, New York, USA. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

In 1964, Andy Warhol was invited to participate in the World’s Fair. For the occasion, he had to create “something related to New York” to be installed on the facade of the New York State Pavilion. Being his only public art ever created, the mural featured enlarged mug shots of criminals from a police department booklet, taking the influence of Duchamp’s 1923 work Wanted, $2,000 Reward. But just after a few hours of being installed, the piece led to objections, notably from Governor Nelson Rockefeller who accused the piece of insulting to his voters. In short, the images showed mostly men of Italian descent, which were at the same time the main voter constituency of the Governor. Consequently, the mural was covered with silver paint just 48 hours after unveiling. Government officials cited concerns about the images’ impact, and various reasons were later speculated for its removal, including Warhol’s dissatisfaction and potential legal issues. Despite its brief public display, the work sparked discussions about censorship, political sensitivity, and Warhol’s artistic commentary.

Andy Warhol, Mao (complete set of 10 works), 1972. Artsy.

But like other artists, Andy Warhol’s artworks have not only faced censorship during his life. In 2012, the Chinese authorities prohibited the display of Warhol’s paintings depicting Chairman Mao during the Andy Warhol: 15 Minutes Eternal exhibition. This was a major retrospective marking the 25th anniversary of Warhol’s death. The tour, featuring over 300 artworks, including iconic pieces like Campbell soup tins and portraits of Marilyn Monroe, had encountered controversy due to its inclusion of ten Mao depictions. The ban disappointed Eric Shiner, director of The Andy Warhol Museum, who emphasized Warhol’s mainstream influence in Chinese contemporary art.

Andy Warhol’s Mao series blended synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink, presenting a unique twist on his iconic repetition. Despite assertions of non-disrespectfulness, the iconic portrayal hinted at irreverence, causing China’s decision to exclude these works from the exhibition. The censorship sparked discussions about art, politics, and the intersection of cultural symbols (even if knock-off copies of Warhol’s Mao works could be found for sale in tourist markets across China).

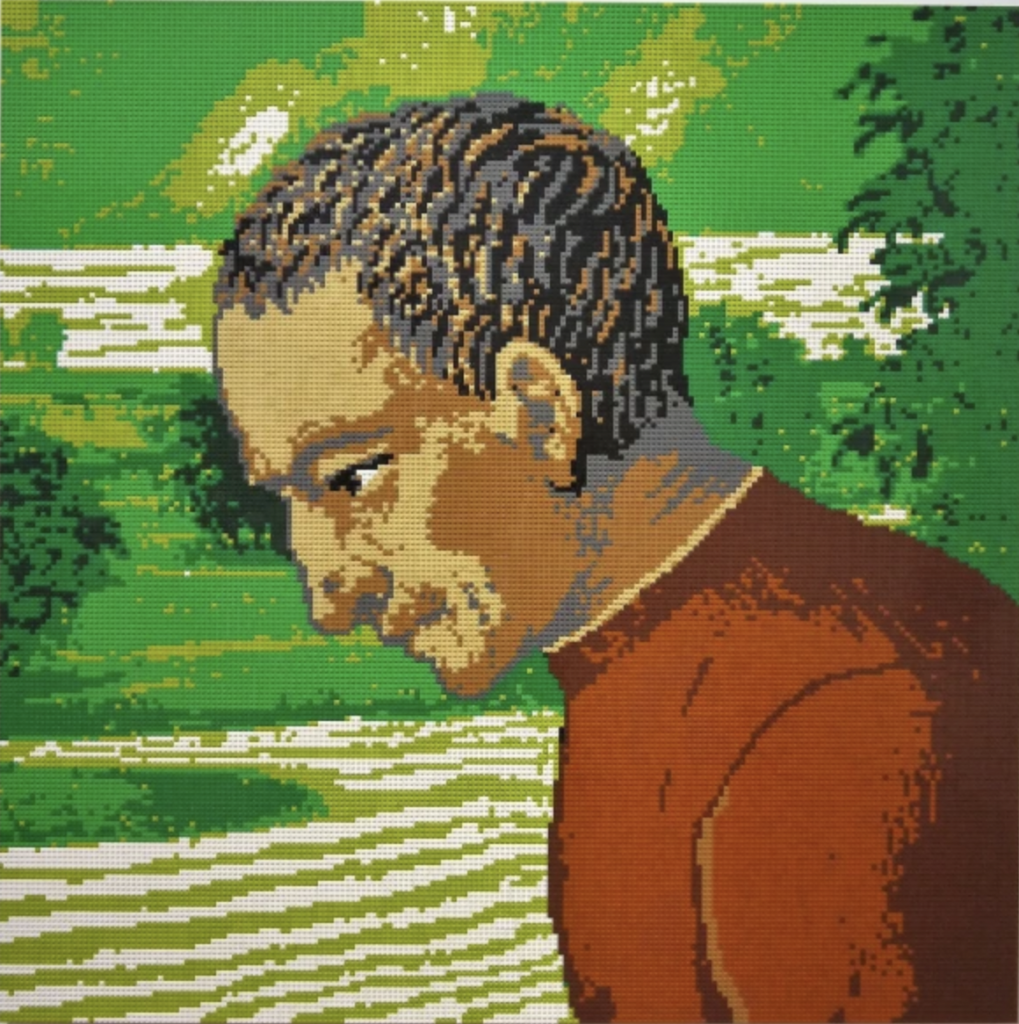

Ai Weiwei, Filippo Strozzi in Lego, 2016, Museu de l’Art Prohibit, Barcelona, Spain.

But when it comes to China, its most recent widely known case of repression against artistic expression is undoubtedly the story of Ai Weiwei. Born on August 28, 1957, Ai Weiwei is a Chinese contemporary artist, documentarian, and activist. As a vocal critic of the Chinese government’s stance on democracy and human rights, Ai Weiwei investigated corruption and cover-ups, notably the Sichuan schools corruption scandal. In 2011, he was arrested for “economic crimes” and detained for 81 days without charge. Despite facing oppression, Ai Weiwei’s resilience and creative activism continue to leave a profound impact on the global art scene. Since he departed from China in 2015, he has resided in Berlin, Germany; Cambridge, UK; and Portugal with his family.

However, the artwork brought to this compilation is not related to his country of origin. As strange as it seems, the ultrafamous Danish company Lego decided not to provide Ai Weiwei with pieces to create a series of artworks in 2015. The artist was creating a series of portraits of dissidents using the pieces, but Lego refused to provide them, claiming they did not want to participate in any kind of political initiatives. It was thanks to the public’s cooperation that the artist was able to complete the series.

Still from Yoshua Okón, Freedom Fries: Still Life, 2014. Yoshua Okón.

The video installation Freedom Fries: Still Life by Mexican artist Yoshua Okón faced censorship at the Tin Tabernacle Gallery in London. Exploring the dehumanizing impact of the corporate environment, the artwork uses a McDonald’s setting to symbolize the alienation of the body within consumer culture. The video depicts a semi-nude loyal customer of McDonald’s lying on one of the franchise tables while a worker cleans the window from outside. Particularly, the gallery chose to exclude this piece from an exhibition due to the depiction of a semi-nude body of an obese woman. Despite an offer to replace the work, Okón declined, underscoring the impact of censorship on addressing the loss of bodily control within the neoliberal framework.

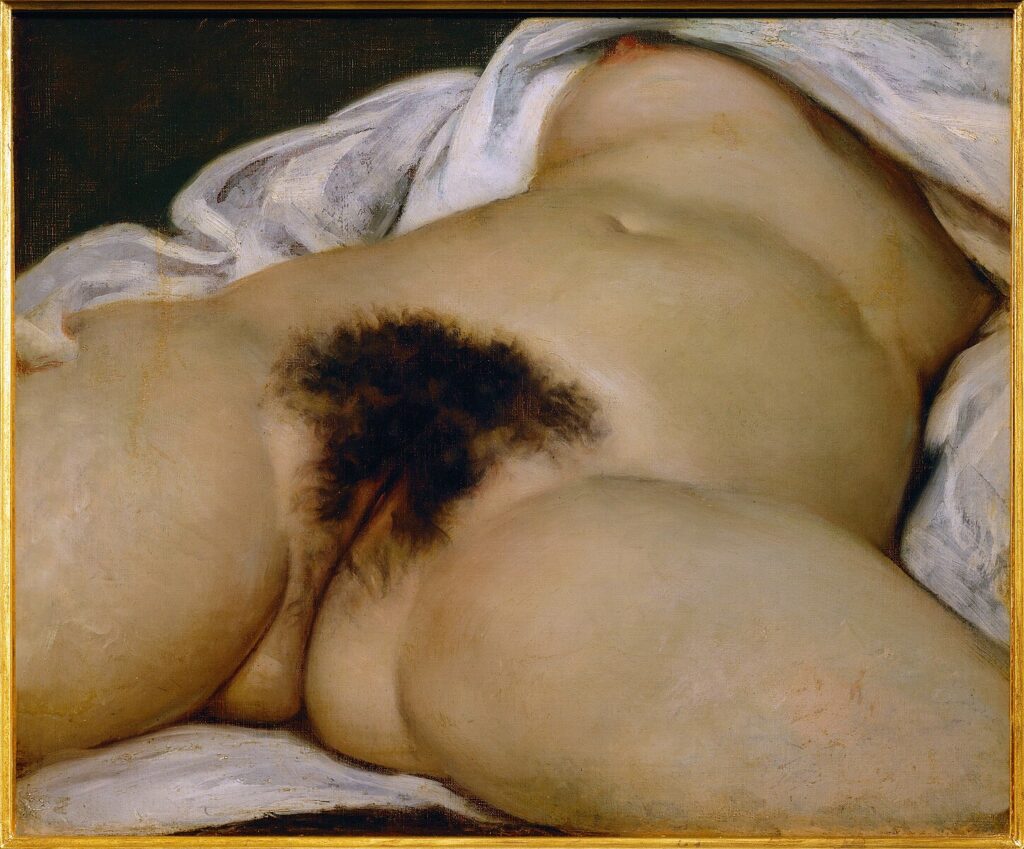

Gustave Courbet, The Origin of the World, 1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

In the present day, the landscape of art censorship has evolved with technological advancements and the proliferation of social media. While the internet provides artists with new platforms for expression, it has also become a battleground where artworks face rapid scrutiny and potential suppression. This contemporary context adds another layer to the ongoing dialogue about artistic freedom, as the intersection of technology, politics, and public discourse continues to shape the boundaries of expression in the art world.

The case of Gustave Courbet’s painting The Origin of the World adds a vivid brushstroke to this problem. An eight-year legal battle between Facebook and a French teacher, Frédéric Durand, unfolded after he posted an image of the realistic depiction of a woman’s genitals on his profile in 2011. Despite Facebook’s “Community Standards” permitting artworks featuring nudity, Durand faced account deactivation. The dispute highlighted the challenges of reconciling artistic expression with platform policies. Simultaneously, social media is increasingly becoming a vital channel for art dissemination. It seems contradictory that contemporary artists must maintain active profiles on platforms like Instagram to be recognized in the public sphere, while these platforms continue to limit artistic freedoms in the digital realm.

This last reflection leads us to the following example of censorship. Furthermore, it is interesting to analyze the two previous cases from a gender perspective. Notably, Instagram consistently censors images featuring women’s nipples, while male nipples remain unaffected (a policy resulting in the “free the nipple” movement). Similarly, there are instances of censorship (as we have seen, not only on Instagram) where female bodies have been censored for not conforming to normative standards of whiteness, thinness, or “perfectly shaved” female bodies. What makes this situation even more disconcerting is Instagram’s paradoxical stance, allowing explicitly sexual content while censoring genuine artistic expressions.

Several instances of censorship on Instagram are featured in the book titled Pics or It Didn’t Happen: Images Banned From Instagram. The artists Molly Soda and Arvida Byström chose to showcase 250 images out of more than 1000 submissions received through an open call to fellow artists on Instagram who had experienced cancellation. The outcome: a book that serves as a memorial for images expelled from the social media platform, highlighting a concerning infringement on the right of expression and, particularly, a significant stigma on the female body. Some of the artists featured in the publication include Isaac Kariuki, Rupi Kaur, Amalia Ulman, Lee Phillips, and the creators themselves, Arvida Byström and Molly Soda.

Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung, Statue of a Girl of Peace, 2011, Museu de l’Art Prohibit, Barcelona, Spain

The final artwork on the list is a piece that led to censorship within an exhibition dedicated to the theme of censorship itself. The Aichi Triennale, an exhibition exploring Japan’s history of art censorship, faced its own ironic fate in 2019 as it succumbed to censorship after just three days of operation. The exhibition, titled After ‘Freedom of Expression?’, was closed due to numerous threats received by the organizers. The artwork at the center of the controversy was a life-sized figurative sculpture, Statue of a Girl of Peace (2011), by Korean artists Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung. The sculpture depicted a “comfort woman,” one of the Asian women forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military during World War II. The shutdown, deemed a “historic outrage” by the curators, came in response to threats that included messages of violence, with one person threatening to set the museum on fire. The incident underscored the fragility of freedom of expression and triggered debates on the role of public officials in protecting artistic expression.

Museu de l’Art Prohibit, Barcelona, Spain. Courtesy of the museum.

Cases of censorship in art, in all their forms, seem to have been in the media spotlight in recent years, especially due to the rise of the extreme right in many countries. Now, some of these artworks and 200 more can be visited at The Museu de l’Art Prohibit (Museum of Forbidden Art) in Barcelona. This museum showcases the comprehensive collection of Tatxo Benet, who, since 2018, has been collecting artworks that have faced censorship, prohibition, or condemnation for political, social, or religious reasons. Its headquarters is Casa Garriga Nogués, a modernist-style house in the center of Barcelona. From works that satirize politicians, such as Eugenio Merino’s portrayal of the dictator Francisco Franco dressed in full military uniform inside a vending machine, to pieces that condemn male violence like Falkova’s Evermust’s Evermust, this is a must-visit museum claiming to be a triumph of freedom of expression.

Gareth Harris, Censored Art Today, Lund Humphries, 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!