Female Rage in Art

Since Auguste Toulmouche’s 1866 masterpiece The Reluctant Bride recently captured the internet’s attention, discussions about female rage...

Martha Teverson 6 May 2024

How is it possible that a 1000 acre industrial site in Dearborn, Michigan, with ninety three buildings that include blast furnaces, mills, a glass plant, a power plant, an assembly line, one hundred miles of railroad track, and even its own docks, can be the source of an artistic endeavor spanning its entire lifespan? If it is the car manufacturing goliath of the Ford River Rouge Complex, then the answer is quite simple: anything is possible!

The Ford Motor Company began creation of the plant in 1917, with the intention of having some of the production for its vehicles being undertaken in this ideal spot, along the River Rouge. By 1928, the complex was completed and it formed the largest integrated factory in the world. The Ford River Rouge Complex was the epitome of production line techniques and the pride of the Ford Company. Historian, David L Lewis said of the plant: “By the mid-1920s, the Rouge was easily the greatest industrial domain in the world” and was “without parallel in sheer mechanical efficiency.”

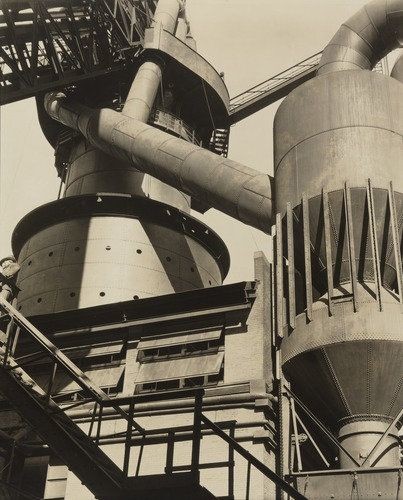

It is the efficiency of the complex that appears to have been the source of inspiration for artists since its inception through to the present day. In 1927, American artist and photographer Charles Sheeler was invited to photograph the Ford River Rouge Complex, as it became known. He did this on behalf of an advertising company, NW Ayer & Son, to make an “extensive collection of pictorial photographs of the plant”. Following his six week visit to the plant Sheeler commented: “The subject matter is incomparably the most thrilling I have had to work with.”

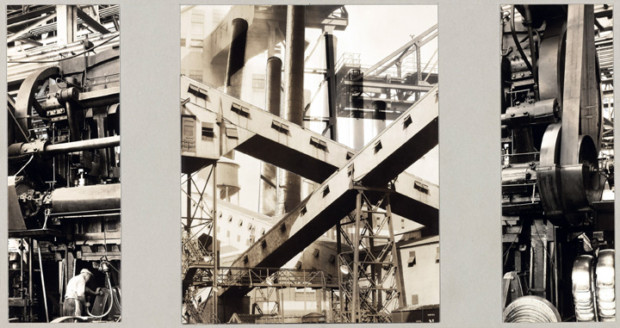

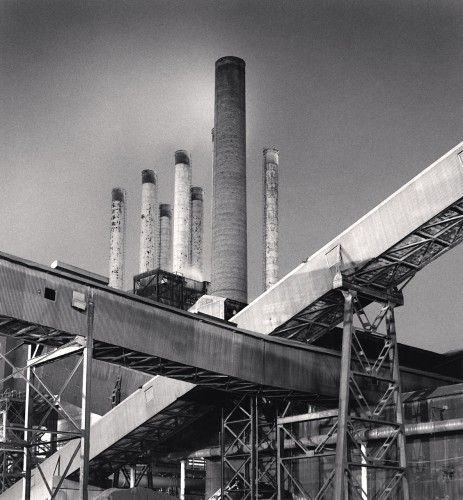

The collage, Industry, demonstrates why Sheeler found the harsh mechanized world of car manufacturing at the Ford River Rouge Complex so ‘thrilling’. The clean lines of the smoke stacks behind the crisscross shapes of the conveyors in the foreground divides the image diagonally to give a strong center to the work. Meanwhile the two narrow panels on either side are two halves of the same image of the stamping press. The might of the machine is given the added power when you see the tiny, solitary figure feeding the press.

In true ‘precisionist’ style, Sheeler was not looking to put forward a social commentary; there are few workers shown in his photographs. The realism here is more of an abstract nature. Sheeler revels in the power of the machinery and the form of the architecture. Furthermore, by distilling this form, he is bringing to the fore the sublime beauty of the shapes.

In terms of his painting, by the 1920s Sheeler was already known for his interiors, still-lifes, and landscapes of Americana. However, his trip to the River Rouge did have a detrimental effect on his painting output. In a letter to a friend he wrote: “As for painting – I am tempted now and then to buy some interesting colors or canvas. I hope they don’t deteriorate before they are used.”

In his time away from painting, he came to the realization that using photographs to create the compositions for his paintings was a way to put onto canvas what he had seen through the camera’s viewfinder.

Although the photographs to some of the paintings have been lost, the two ‘landscape’ paintings that Sheeler produced clearly demonstrate how the wide-angle lens would have supported the magnificence of the site.

The aptly named ‘American Landscape’ shows a panoramic view of the plant, with the boat slip in the foreground. This can be seen in the photograph Sheeler took of the Salvage Ship in 1927.

The horizontals of the painting divide the canvas into three distinct areas. Small touches, such as the ladder in the bottom right hand corner, add a sense of mystery to the composition. The stillness contrasts with what would be a busy working scene – only the billowing smoke and the tiny figure running along the track give a sense of movement. The scene could almost be described as ‘idyllic’.

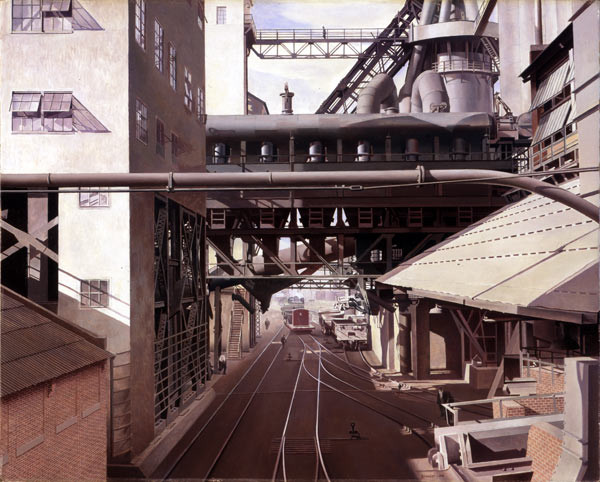

The same sense of an idyll is also replicated in Classic Landscape from 1931. The ‘ice cream’ palette employed by Sheeler, in this image from the other side of the cement plant silos, simply exudes serenity. The smoke mingles with the clouds in the perfect blue sky. The rail tracks diagonally divide the canvas and draw the eye speedily into the distance and break out of the canvas and into the imagination.

In his photographs as well as his painting, Sheeler avoided the hustle and bustle of the working world of the plant. Here in City Interior, Sheeler again takes the enormity of the buildings and, by populating it with only a few figures, he conveys the cathedral-like feeling of the different layers before us, leading the eye skywards in a series of horizontal planes.

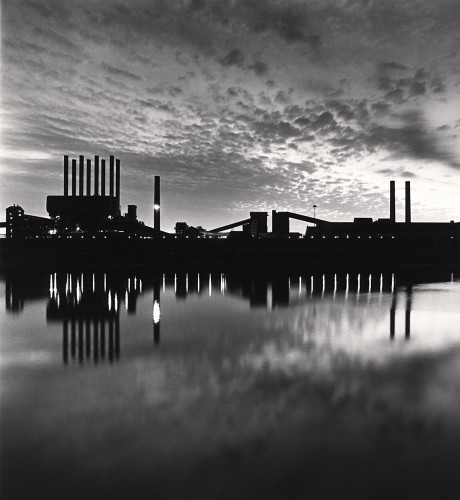

At the beginning, it was mentioned that the Ford River Rouge Complex has inspired artists since its inception; Diego Rivera completed a set of murals of the plant in the 1930s; Robert Frank photographed the workers of the plant in the 1950s. However, the plant has continued to inspire and, more recently, the British photographer Michael Kenna spent four years from 1991-1995 photographing the plant, having followed in Sheeler’s footsteps.

In his photographs, Kenna brings the industrial drama of the plant to the fore. Although the plant is still active, much of it is falling into disrepair. Kenna creates a sense of melancholy emptiness. In a recent interview with Wanderlust magazine Kenna said: “Parts of the Rouge were active and quite dangerous, with moving cranes, trains, and enormous containers of molten steel and slag. Other parts were disused and quiet, rusting and decaying, with vegetation growing around abandoned machinery. Ships would come in and out the harbor. The scenery constantly changed depending on the conditions.”

Photographed through steam and smoke, from low angles and in long exposures in the evening light, Kenna continues the legacy that Sheeler began by showing us the precision of power and might of the industrial landscape coupled with a sense of its gradual decay.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!