10 Facts You Didn’t Know About Anthony van Dyck

Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish Baroque painter of remarkable skill, left an indelible mark on art history. His signature style of refined portraits and...

Jimena Aullet 24 October 2024

Francisco de Zurbarán was one of the major Spanish painters of the 17th century. He is especially known for his religious subjects and for the Caravaggesque tenebrism of his paintings – which is precisely why he is also known as the Spanish Caravaggio.

Francisco de Zurbarán was born in Fuente de Cantos, Spain, in 1598. At 13 years old, he began his apprenticeship with Pedro Díaz de Villanueva in Seville. Zurbarán stayed in the city from 1614 to 1617. It was also during this period that Zurbarán befriended Diego Velázquez, who was also an apprentice in Seville at the time. They still kept in touch for years later.

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Apparition of Saint Peter to Saint Peter Nolasco, 1629, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

After the end of his apprenticeship, Zurbarán went back to his native province (Badajoz) and established himself in the city of Llerena. At 19 years old, he became a father. His first daughter from his first wife, María Páez, was born in 1618. María might have died in the birth of their third child in 1623. In 1625, Zurbarán married his second wife, Beatriz de Morales, and two decades later, he got married for a third (and last) time to Leonor de Tordera. His several marriages were not an unusual occurrence at the time.

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Immaculate Conception, c. 1630, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

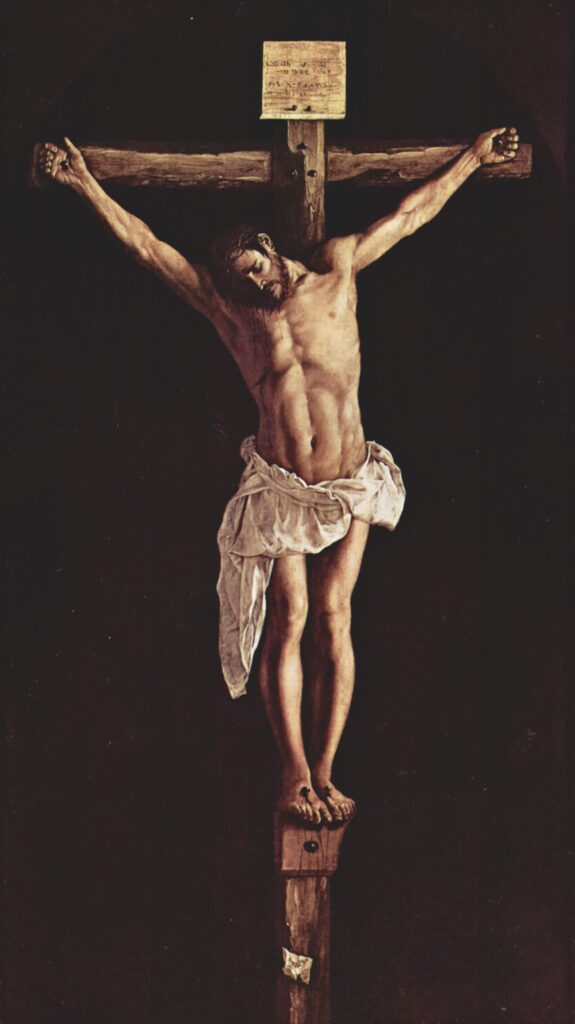

None of his paintings from before 1627 are known to us. Christ on the Cross is his first main signed and dated work in the tenebrist style. Tenebrism is marked by an intense contrast between light and dark. The term comes from the Italian word ‘tenebroso’, which means dark, gloomy, or obscuring. In this type of painting, significant areas and details are illuminated, standing out against the darkened ones. Often against a background of intense darkness that offers no distractions from the image’s focus, the dramatically lighted forms are emphasized.

In this painting, the figure of Christ emerges from the dark background, which is devoid of usual narrative details such as the presence of the Virgin Mary or other mourners. The focus of the viewer is directed solely to the body of Christ in his sacrifice – it is as if the lit figure is emerging from the darkness into our space as viewers. The anatomical realism of the body brings a very humanized aspect to it. At the same time, it is also idealized in quiet and graceful beauty.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Christ on the Cross, 1627, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Zurbarán painted around 30 images of Christ on the Cross – it was one of his central themes. This one, in particular, was so admired by his contemporaries that, because of it, he later received an invitation from the City Council of Seville to live again in the city.

Zurbarán became Seville’s official painter in 1629, starting the most prestigious decade of his career. In the 1630s, commissions from outside of his city began to increase. His workshop exported several paintings to South America, and a commission from Philip IV marked a trip to Madrid.

In the 1640s, though, things started to decline. Zurbarán kept working but, affected by Seville’s social and political environment, artistic commissions went downward. The city was suffering from unemployment and poverty, and a great plague reduced its population by almost half in 1649. Perhaps in search of work, Zurbarán went back to Madrid in the 1650s, dying there in 1664.

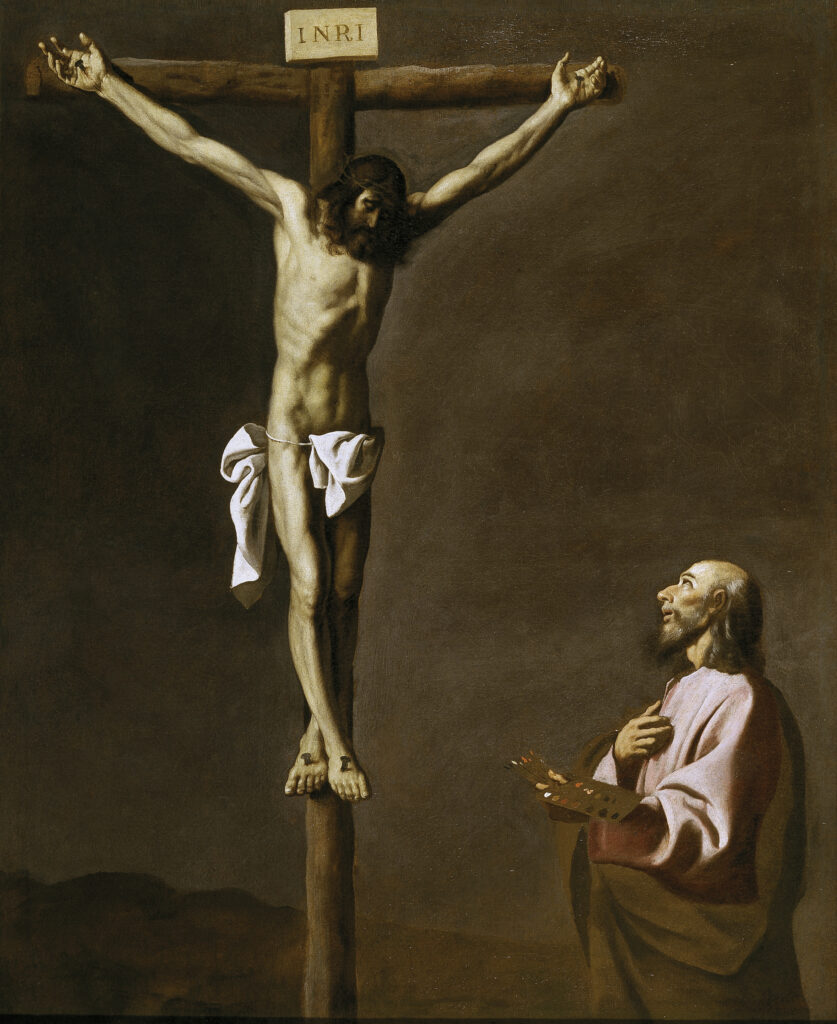

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Crucified Christ with a Painter, c. 1650, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Zurbarán painted for monarchs, but his main patrons were Spanish religious orders (at times, he even lived in the monasteries he worked for). His religious paintings met the needs of the Counter-Reformation, which aimed to combat the Protestant Reformation and revive the Catholic spirituality. Zurbarán’s devotional realism was emotionally powerful and inspiring, thus serving the Catholic Church’s desire of touching the souls of the faithful.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Agnus Dei, 1635-1640, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

This painting may look like a mere still-life, but it actually carries a more profound religious meaning. Here we see a lamb with its legs tied up together. He is very still, but he is not actually dead (as is expected of still-life paintings). It is as if he is waiting for his sacrifice. He is resigned – not fighting against it, but accepting his fate. In this painting, Zurbarán brings emotion to what could simply be the still-life of an animal about to become a meal. In the context of 17th-century Spain, this image would easily suggest to the viewer the idea of the Lamb of God (Jesus Christ, the best-known sacrificial image of the Catholic Church).

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was one of the most prominent Italian Baroque painters. He is best known for the use of theatrical light and dramatic chiaroscuro in his paintings. Caravaggio was very influential at his time and the term Caravaggism is used to describe paintings that were executed in his naturalistic and dramatic style.

Left: Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Francis in Meditation, 1639, National Gallery, London, UK. Wikimedia Commons (public domain); Right: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Saint Francis in Prayer, c. 1606, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

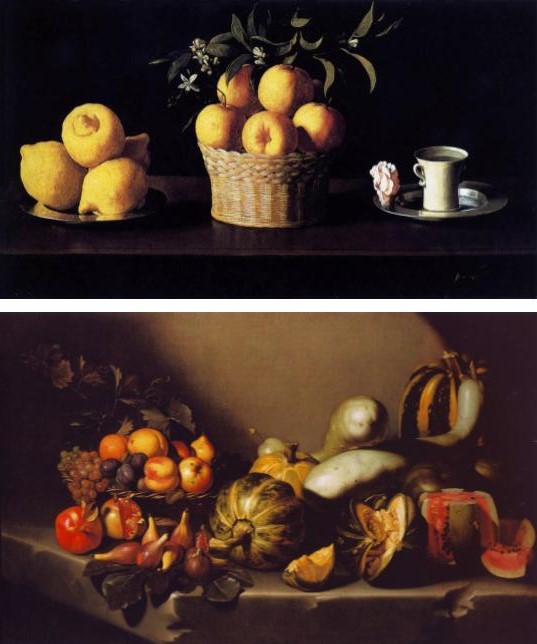

Zurbarán’s style follows the tenebrist characteristics of Caravaggio’s last works. His brushwork is looser than the Italian’s, but we can notice the similar use of dramatic and theatrical light in both artists. Zurbarán’s realism is a bit more reserved – his paintings have been described as austere and spiritual – and his use of contrast is softer. These tenebrist and Caravaggesque characteristics mark years of Zurbarán’s career until around 1635, when some changes in his style can be seen (perhaps influenced by his friend Velázquez’s example).

Top: Francisco de Zurbarán, Still-life with Lemons, Oranges and Rose, 1633, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain); Bottom: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Still Life with Fruit, c. 1603, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!