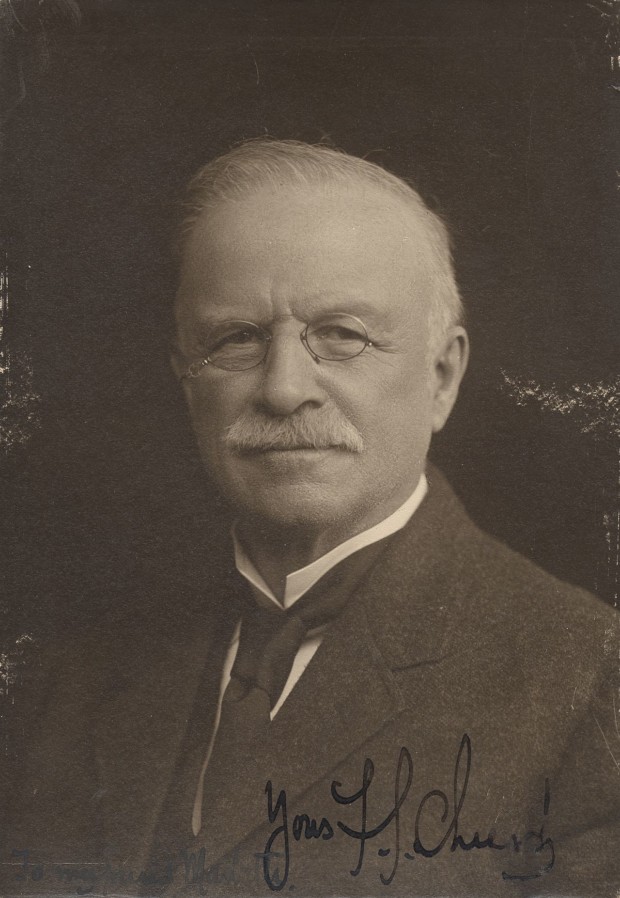

A lifetime of training could not have prepared Frederick Stuart Church for 1863. But his works of fantasy that came after clung to and perhaps even dictated national Romantic bent: idyllic portraits of women and animals existing in perfect harmony.

Only eighteen years old, Church enlisted in the Chicago Mercantile Light Artillery. He knew his parents were grooming him to be a businessman. He had prospects with the then-fledgling American Express Company, having worked for them since thirteen. What he didn’t know was that he would be amongst the twenty percent of men from his battery to survive the American Civil War.

Church’s Light Artillery was directly involved in some of the heaviest battles of the war’s western theatre. Hauling cannon by land and water over the course of three years, they participated in such storied battles as Sherman’s March to the Sea (a slash and burn campaign that set fire to much of the American south) and the Siege of Vicksburg, considered by some to be the turning point of the war. At one point, his battery refused to fight as infantry, spending thirty-five days in a military prison.

When peace finally prevailed in 1865, Church returned to Chicago, but he left his business intentions behind. Instead, he headed to New York and began etching, eventually becoming a staple of the publication Harper’s Weekly. In this high era of American etching and genre painting, Church set himself apart with his dreamlike depictions of animals and young women.

In his time, the soldier-turned-painter portrayed highbrow socialites and intrepid travelers to personified birds and tamed jungle cats. However, what remains particularly distinct about his work is the sensitivity and innocence with which he handled his scenes. Having witnessed so much horror and death, he preferred to create idyllic worlds wherein the natural relationship between humans and beasts was in balance.

The high romantic themes of his work contain imagery that prevailed in U.S. illustrative and painted art at the time. “A Symphony, Nineteenth Century” depicts a woman playing a stringed instrument to a cupid who lies above her, almost perched. Ivy inquisitively crawls past them both, as well as floating above along a nearly invisible wall. If this was a Greek bas-relief scultpure, the woman might be holding a lute; in the case of “Symphony,” it’s a banjo of sorts.

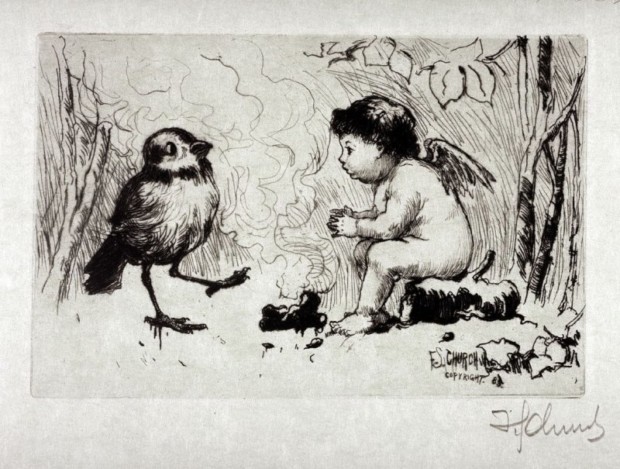

“A Cold Morning” is a similar scene, though in this case a cupid – surprised by a visitor – shares the warmth of small fire with a baby chick. Smoke wafts between them, and the bird raises a foot; is it to better warm it or slowly back away?

“Two Birds” is a rare example of a piece by Church that doesn’t portray a woman. While the careful attention to value and form apparent in “Symphony” remains, Church’s lines are stiffer and sometimes more erratic. The legs of the birds walk stiffly, resembling the grasses behind them. Their reflections in the water are nearly invisible; a shadow cast to their right is a swirling cross-hatch that dares to take the viewer out of the scene altogether.

With the Civil War finally over, it there was likely a prevailing sentiment in the U.S. towards a past time, a peaceful one that emphasized beauty, harmony, and music. This would have increased demand for Church’s works, providing him ample opportunities to explore these themes.

Two of his predominant subjects – women and wildlife – appeared in the same frame together more often as time passed. “Woman and a Crane” creates a rhythmically balanced composition in which a woman’s bent and crossed legs mimic the rigid passé of a standing crane. Both are at rest, consilient in action and form. They face each other, at once the observer and the observed.

Meanwhile, at bottom right, most likely the same woman is sketched, flanked by two massive cats, probably tigers. While the power in the top image comes from its equilibrium, the strength in this sketch comes from the beasts. The woman, placed squarely between them, keeps her head down while the cats’ eyes are up and vigilant. The tiger to the left opens its maw, possibly in warning; they appear to be her guards, and she their queen.

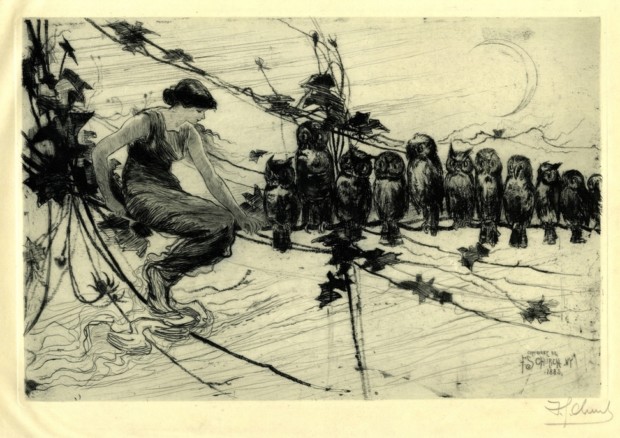

Church’s compositions of women and animals evoked both strength and harmony simultaneously. “A Lesson in Wisdom” seems to exist in neither space nor time; the woman’s feet dangle into the water (or mist), leaving tenuous ripples behind them, while the moon shines overhead in a thin crescent. Though the owls are far greater in number, they all remain balanced on their perch. One is left to wonder who is imparting wisdom to whom, since the birds gaze at the woman whereas she herself stares downward. Is she looking at the first owl or past it at the expanse below?

Painting afforded Church a different method with which to achieve the tenderness he often strove for in his etchings. He played with both disguising the brushstrokes and making them evident, creating either a soft, universal luminance or a wind-blown dynamism indicative of a dream.

“Supremacy” depicts a walking embrace between a woman and a lion in almost impressionistic color. The sky, pink and purple, is reflected in the diaphanous gown that wraps the woman. Near her legs, it matches the lion’s mane, itself the same golden hue as the fields in the background. Her arm over his head, he nuzzles into her, quite literally attached at the hip.

Harking back to the famous Hellenistic sculpture, Church’s “The Viking’s Daughter” strongly resembles the pose of the Nike of Samothrace. Though her arms are not outstretched like the statue’s, at first glance it seems as though she shares the Nike’s widespread wings. Upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent that this is instead her flowing, golden hair. The same wind carries a flock of gulls behind her, completing the winged illusion.

The daughter’s pose is certainly more relaxed than that of Nike, but her power comes in the wind that follows her. She and the earth remain in balance, largely in the painting’s palette. As in “Supremacy,” her dress bears the colors of the land and sky around her, an ambiguous field at dawn. She appears to have risen with the sun and the wind, calling the first of the birds to wake with her. Were they beckoned with the flute by her side?

This is the penultimate example Church’s perceived relationship between humans – or perhaps just women – and animals. Whereas the Nike was a goddess, the Viking’s daughter is a mortal; yet the close resemblance between the two suggests that the divinity of the gods is here on Earth. This woman doesn’t need wings – appendages of either a goddess or an angel – to be holy. The earth will exalt her so long as she exalts the earth.

From a straight and narrow path, to a life ravaged by war, and back again to the countryside, Frederick Stuart Church painted from the fantasies of his soul. He saw in the young women he portrayed a wisdom and dominion that reflected in the natural world, drawing the two almost inexplicably to each other. His was an imagined reality just close enough to the truth that one hopes it could be real. Church brought about peace – if not an end to conflict, a peace of mind – by first creating it on the canvas.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City published a fun article on a collection of Church’s notes to friends, on which he sketched himself (supposedly) as a bear, amongst other drawings.