For centuries, China was one of the greatest and wealthiest civilizations, and perhaps it is now returning to its historical position. Artist Fu Wenjun witnessed the recent rapid changes and that’s why his art is positioned on the border between the two worlds of tradition and technological developments.

When I was a child I had this romantic vision of China as a place with people working on rice fields, wearing conical hats and drinking tea in pretty tea houses. When everything started being made in China I thought that the country was nothing else but factories with people working for next to nothing making goods for the rest of the world. I felt sorry for China.

Then, in 2012, I arrived in the 15-million-strong sprawling city of Guangzhou and realized that the country is none and all of these things at the same time. I discovered a China of diverse cultures, hospitable people, delicious food, nice weather and of course interesting art. Nothing was how I expected it to be, especially the technological advances including high-speed trains, avant-garde architecture and a well-developed underground system, leaving the European cities not so much in the centre of the world any more. There was a significant amount of poverty there as well. It saddened me, but overall I felt amazed by China.

China has experienced rapid industrialization, which started only about 35 years ago, and has managed to transform itself from a vastly impoverished agricultural land into a formidable industrial powerhouse. Artist Fu Wenjun (born 1955) witnessed the recent rapid changes and maybe this is why his art is positioned on the border between two worlds: tradition and technological developments. In his own words:

I tell the viewers an old-style tea house still exists in my hometown. Drinking tea, talking about the world, is always a way of life in this ever-changing city. The world is changing so fast, but maybe not for everything, everyone, everywhere.

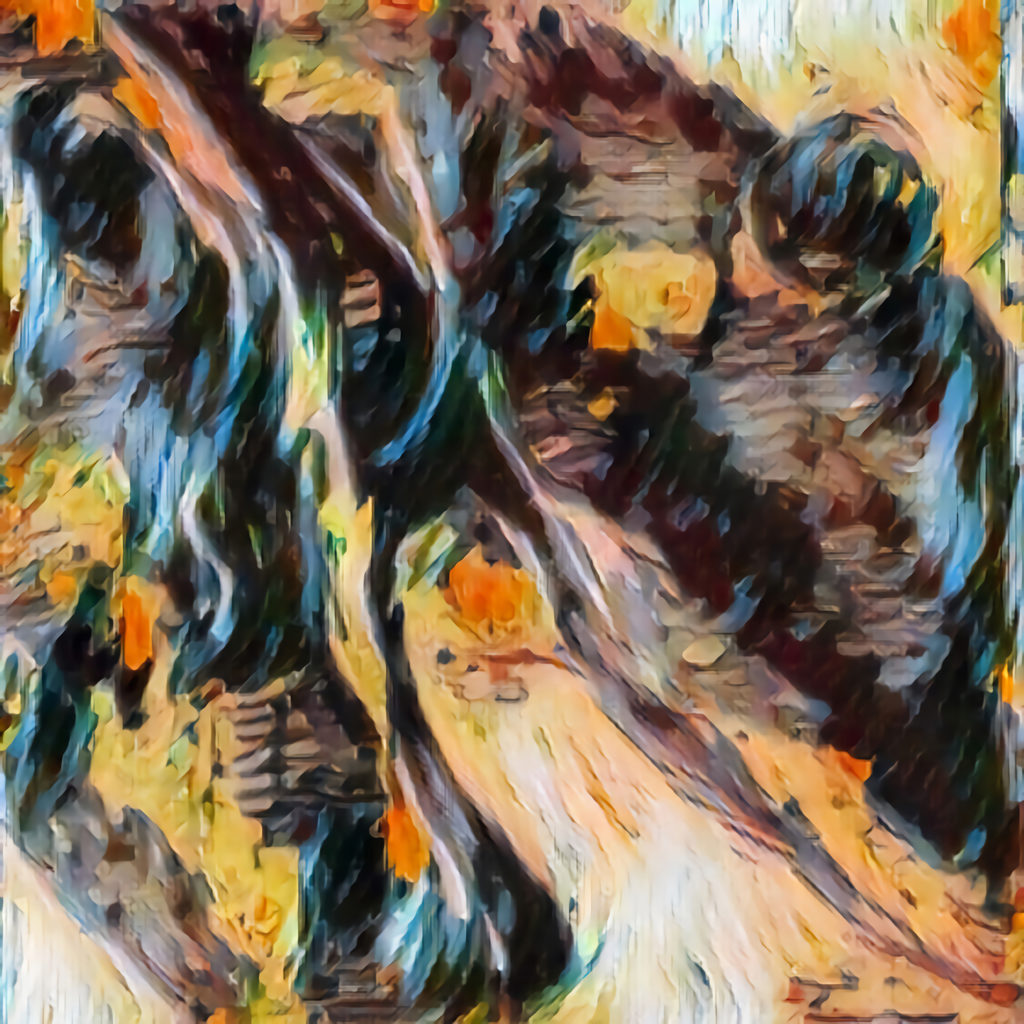

This feeling of nostalgia is present in Wenjun’s semi-abstract series Misplacement (2017–2018), which refers to the traditional Chinese ink art. After Fresh Rain in the Mountain (2017–2018) is a square photograph with abstract black lines, sprawling across a white background, reminiscent of spilt ink. For more than two thousand years, ink has been the dominant medium of painting and calligraphy in China.

Since the early 20th century, however, this tradition has increasingly been challenged by practices introduced from the West. Wenjun does not actually use ink but rather embodies an inky aesthetic using a technique he developed himself: digital pictorial photography. He combines painting elements, digital manipulation and multiple-exposure of photographic images. He takes many photographs during his travels and uses them as a raw material. After returning to his studio, Wenjun manipulates the images by digitally splitting them, recombining and superimposing them on each other. Wenjun originally studied painting at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, one of the most prominent art academies in China, but later started using a variety of media:

The study of painting opened to me the door of art and I never gave it up. Then I found photography very interesting. For contemporary artists, a single medium cannot meet our needs of artistic expression (…) Multi-media and interdisciplinary creation is a must choice. I also work with sculpture, installation, digital art and now my works are mainly mixed media.

Among artists that Wenjun considers important for his practice are Westerners Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, Man Ray and Ansel Easton Adams, but also Chinese artists such as Zao Wou-Ki and Qi Baishi.

Abstraction is not new in Chinese art. In fact, the abstract expressive potential of a brush stroke lies at the very core of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Wenjun benefits from this heritage of abstract and symbolic qualities of Chinese painting. He has also engaged with Western nonfigurative art. In that sense, Wenjun’s practice combines the East and the West. His Misplacement and Human Nature for Food (2017–2018) could be Western works because they are very abstract, but actually in their essence they remain Chinese. For Wenjun, abstraction represents inner landscapes just like the traditional Chinese literati paintings did.

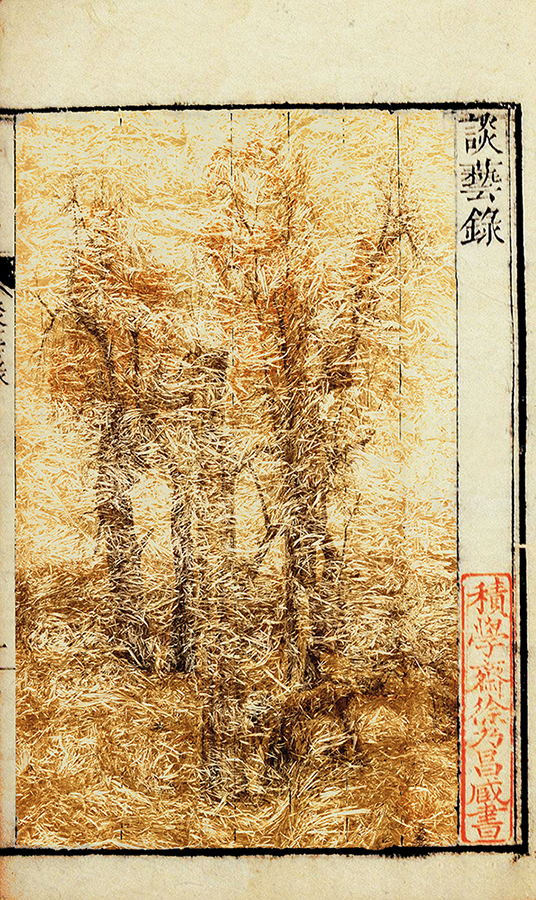

Wenjun admits that he has no preference between abstraction and figuration and it is more a spontaneous choice. His series A Wind from Yesterday (2016–2017) superimposes pages of woodblock printing from the Song Dynasty (960–1279) with photographs of trees, and it is printed on archival Giclée paper. The final effect looks like a contemporary version of traditional Chinese landscape painting. Mao Qiuyue wrote that Wenjun’s art has some of the main characteristics of Chinese traditional art, including the contrast between cavalier and focus perspective, the concentration of ink smudges and colors, and a mixture of vividness and subjective expression.

Images are monochromatic, with contours of trees slightly blurred and disappearing into the mist in an almost Impressionist way. Recognizable elements like Chinese characters are also present. Traditionally, this kind of painting put emphasized the harmony between man and nature, as per Taoist and Buddhist concepts, and the same intention seems to be present in A Wind from Yesterday. The artist reinterprets tradition and celebrates the Chinese aesthetic of “classic elegance” using contemporary means such as photography and photographic postproduction.

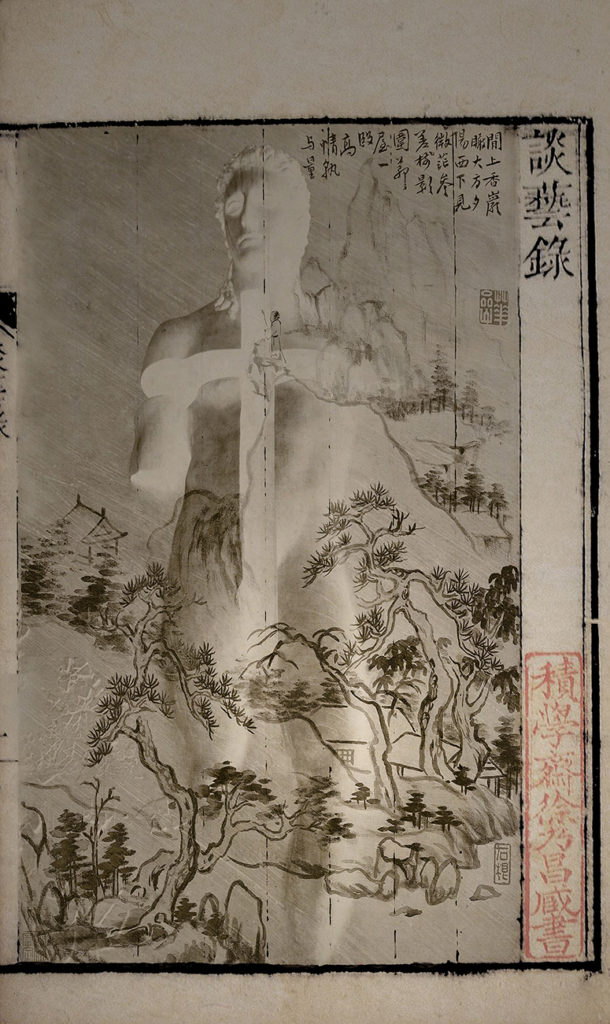

Many of his figurative works mix Western elements with Chinese tradition, such as his series Harmony in Diversity (2016–2017), where Wenjun uses a similar technique as in A Wind from Yesterday, but this time combines Western classical sculptures with Chinese ancient painting.

Images of marble statues of Venuses and Apollos emerge from Chinese mountainscapes, with hills, trees, houses and waterways. Colors are monochromatic, mainly black and white with distinct Chinese writing and a red seal. The writing, indecipherable for a Westerner like me, presumably has been taken from the original Chinese scroll. Peng Feng wrote about this series that it is a metaphor for dialogue between Chinese and Western cultures and indeed, thanks to Wenjun’s superposition technique, these two different aesthetics seem to be harmonious. Wenjun admitted that:

We live in a world people are easily and closely connected. Fully taking advantage of the conveniences the era provides, keeping an open mind to other cultures, could make me stand higher and see far. The more I know, I find that there are many commonalities in different cultures.

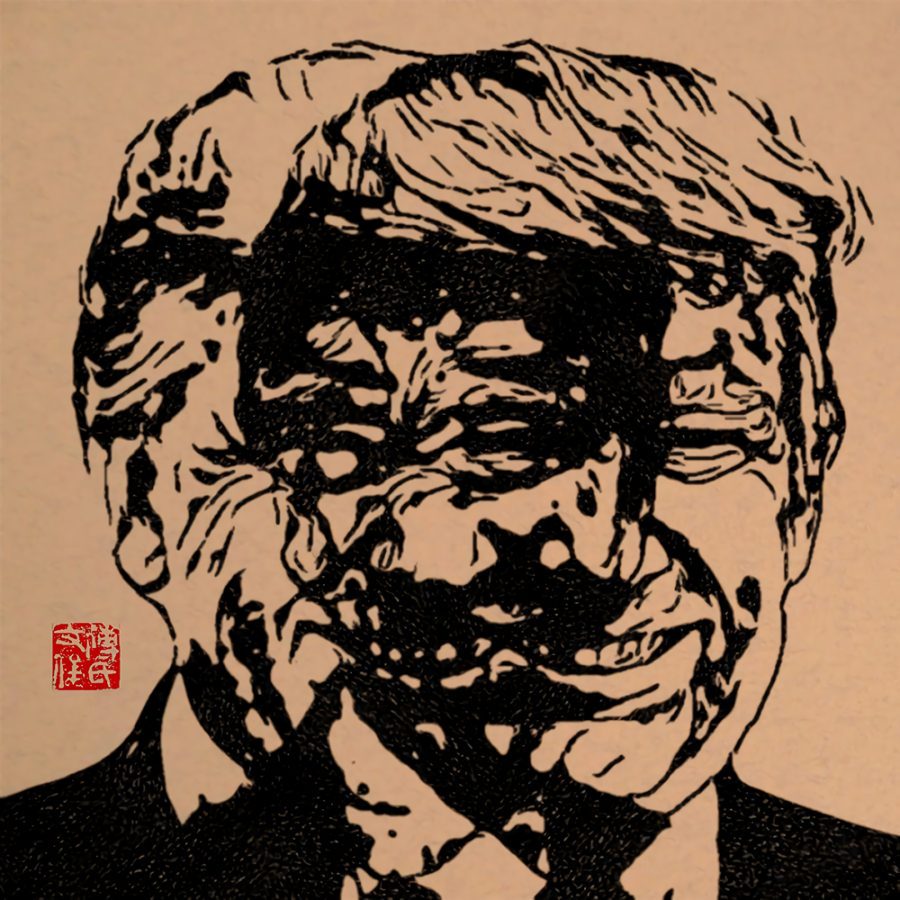

Wenjun’s latest series Passage of Time (2019), although made in his digital pictorial photography technique, stylistically refers to Chinese ink painting, but thematically to Pop Art. In this series, the artist has taken imagery from mass culture and media, such as portraits of Theresa May, Donald Trump, Osama bin Laden and Mona Lisa, and stripped them down to simple black contours, similar to those seen in street art stencils. Portraits are multiplied, deconstructed and superimposed on each other, creating uncanny, almost monstrous portraits – perhaps this is the artist’s reflection on the complicated state of today’s world politics.

Wenjun’s work may be understood as the extension of China’s traditional culture, but it should also be appreciated from the perspective of global art. It embraces new media in a rapidly developing world, but it does not let go of Chinese historical artistic paradigms, layers of meaning and cultural significance. His experience of living in China, a country with a rich heritage and a complicated history, is very present in his art, but Wenjun is a curious artist looking out and traveling a lot. He takes inspiration from mass media, everyday life and found archival imagery, and he creates works that are full of nostalgia for the disappearing world but also concerns about the problems facing people around the world today.

We love art history and writing about it. Your support helps us to sustain DailyArt Magazine and keep it running.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!