In 1904, an extensive report made for the British Archaeological Association revealed that in England there were more wall paintings of Saint Christopher than of any other saint. However, this gentle giant of a man was equally popular on the Continent, and some fine medieval representations have survived in Central Europe as well.

Whether Saint Christopher really existed has been a subject of debate. He is said to have lived and died a martyr’s death in the third or fourth century AD, either during the reign of Roman Emperor Decius or Maximinus II Dacian. His name only added to the confusion. Meaning “Christ-bearer” it could apply both to a specific person or to several different figures, either real or legendary. If the latter was the case then it must have been a general title rather than a name.

Stories about Christopher’s life and death began to circulate in the sixth century in Greece only to reach Western Europe three centuries later. Ever since, he has been one of saints most often represented in art and one of medieval Europe’s favourite saints. Most saints’ attributes relate to their life or the circumstances of their death. Why, then, was Saint Christopher usually shown as a giant carrying Christ across the river? Legend has it that, in search of the greatest king he could serve, Christopher found himself in the service of the Devil. But as he soon observed, there was someone even more powerful whom the Devil feared: Christ. Christopher decided to serve Christ, but he did not know where to find him. In search of him, he turned to the hermit to ask for advice. The wise man told him to use his extraordinary physical strength to help people cross a dangerous river where many lost their lives. This service would be pleasing to Christ. Christopher followed his advice. As he was eagerly and dutifully performing this dangerous task a child asked him for help. Christopher placed it on his shoulder, but as he was carrying it to the other side the child grew heavier and heavier. Still Christopher did not give up. When they finally reached the other bank, he asked whom the child was. As it turned out he helped Christ himself.

As he offered protection to travelers and against sudden death, images of him were usually placed opposite the south door of the churches, so he could be easily seen. Together with Saint George and Saint Martin, he was the patron saint of knights. According to chivalric code, a knight should be as valiant as Saint George who slew the dragon, as merciful as Saint Martin who shared his cloak with a beggar, and as loyal as Saint Christopher who carried the boy Christ on his shoulders across the river, never abandoning him.

In iconography of this saint, exceptionally rare depictions have survived in the Lower Silesia region of Poland, in the ducal tower-house of Siedlęcin and in St Peter and Paul’ s Church of Lubiechowa. Dating from the early 14th century and bearing close resemblance in style, they were probably made by the same artist.

The tower is famous for its unique set of paintings. Dating to the early fourteenth century (as the tower itself) they show the marvelous exploits of Sir Lancelot of the Lake, but the central figure is that of Saint Christopher. Here, as art historians suggest, Lancelot and Saint Christopher were intentionally put together as opposing figures, the former having been the one who betrayed his lord, the latter who served his faithfully. Saint Christopher, the epitome of loyalty, was to serve as a reminder of the knight’s first duty and the necessity of keeping faith and leading a good Christian life. Believed to have superhuman strength, Saint Christopher was usually depicted as a giant of a man, bearded and well-built, however, Christopher of Siedlęcin has been shown in a different way. He is usually identified by two key attributes: a staff and the act of carrying the baby Christ across the river. In the tower he performs his defining act but, as art historians point out, quite extraordinarily he is depicted as a gentle youth in lyrical pose rather than a strong man in his prime. The sensitive modeling of his face and flowing handling of his robe give him an idealized beauty. Instead of carrying Christ on his shoulder, he engulfs him in a tender embrace within the shelter of his arm. Little wonder that in 1887, when the paintings were partly uncovered from the layer of whitewash, their discoverer took Christopher for the Virgin Mary. There were voices opting for Christopher from the beginning, but this was only confirmed after nearly one hundred years, when the complex conservatory works carried out in the tower in 2006 helped to dispel all doubts. Firstly, a medieval lady could never wear a robe exposing her legs in such an indecent fashion. Secondly, the figure’s feet are too large to belong to a woman, and thirdly these large feet are submerged in water with small fish swimming around them, the definite proof of his true identity.

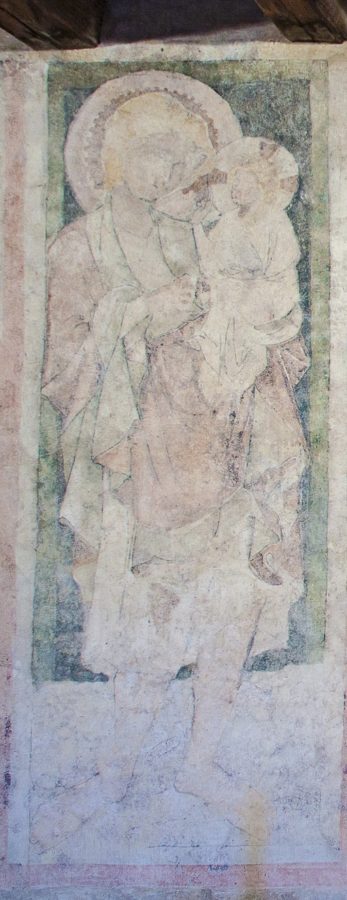

A similar representation of Saint Christopher has survived in the nearby village of Lubiechowa. In the local church, where a whole set of medieval wall paintings was discovered in the late 1960s, a large figure of Christopher adorns the northern wall of the nave. And although the colors differ from the ones used in the Great Hall of the Siedlęcin tower, there is a close resemblance in style and composition. Hence art historians’ conviction that the two works are by the same artist. Not known by name, he probably came from northern Switzerland, from such important centres of courtly culture as Constance and Zurich. The villages of Siedlęcin and Lubiechowa belonged to the tower founder’s and his household knights. With all probability the duke commissioned the work in the tower itself, but also lent the artist to one of his men to adorn the walls of the Lubiechowa church. Here Christopher is again shown as a gentle youth rather than the epitome of strength.

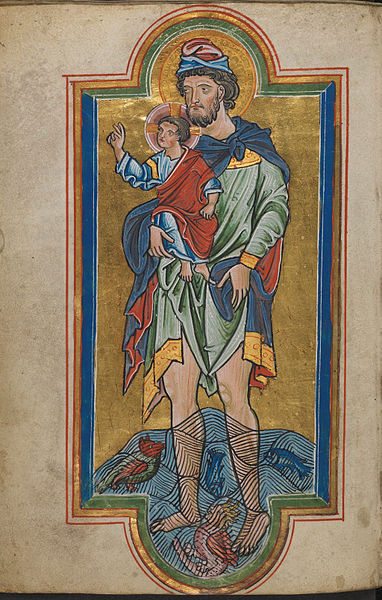

An interesting example of a Saint Christopher representation survives in St Francis of Asissi Church at Pełcznica. Art historians and historians alike think that here the portrait of the saint is in fact a crypto-portrait of Duke Bolko II the Small, one of the Silesian Piasts, representatives of Poland’s first ruling dynasty. The saint bears close resemblance to the duke as he has been shown on his tomb effigy preserved in Krzeszów Abbey and on his seals. In addition, Christopher’s head has been adorned with a ducal mitre. Thus, the whole representation can be read as an allegory of a perfect Christian ruler, protector of the Church and the poor souls exposed to sin. On a merrier note, if the art historians’ are in the right and the painting does show the said duke, the dimensions would tell us something about Bolko’s sensitiveness about his height. After all he was called ‘the Small’ not without good reason.

Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik