Skiing in Art History

Artists have long captured the magic of snow. During the 19th century, when winter sports like skiing, skating, and sledding became more popular in...

Louisa Mahoney 5 February 2025

George Bellows’ boxing paintings capture the dynamic action of a vicious sport, its blood-thirsty fans, and the grace and beauty of its athletes. A chronicler of gritty Americana, Bellows painted picturesque landscapes as well as the sordid scenes of a crowded industrial city, the poor, soldiers, and sports. His six boxing paintings are among his most iconic works, a confluence of high art and low culture.

George Bellows. Photograph by Peter A. Juley & Son (public domain).

Before becoming a notable painter of American Realism, George Bellows (1882–1925) was a six-foot-two-inch (1.9 m) standout basketball and baseball player at Ohio State University. He attracted attention from the Cincinnati Reds, but traded in his bat for a paintbrush and moved to New York City in 1904 to study under renowned painter Robert Henri. Still, sports remained of high interest.

As part of the Ashcan School—a group led by Henri and including George Luks, William Glackens, and John Sloan—Bellows and his compatriots showed the coarse reality of everyday life. In addition to painting, many of the Ashcan artists worked as illustrators for newspapers and magazines. This influence can be seen in the narrative boxing paintings.

George Bellows, Club Night, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

When Bellows arrived in New York, boxing enjoyed both wild popularity and shaky legal status. Bellows’ studio stood across the street from Sharkey’s, a boxing bar and the setting for Club Night (1907) and Stag at Sharkey’s (1909). Though dated years apart, they were likely painted around the same time. Both make use of dramatic lighting that accentuates the seedy nature of the spectacle and highlights the lean muscles of the fighters. Stag at Sharkey’s however, is painted more loosely, with longer brushstrokes matching the action of the fight.

George Bellows, Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, USA.

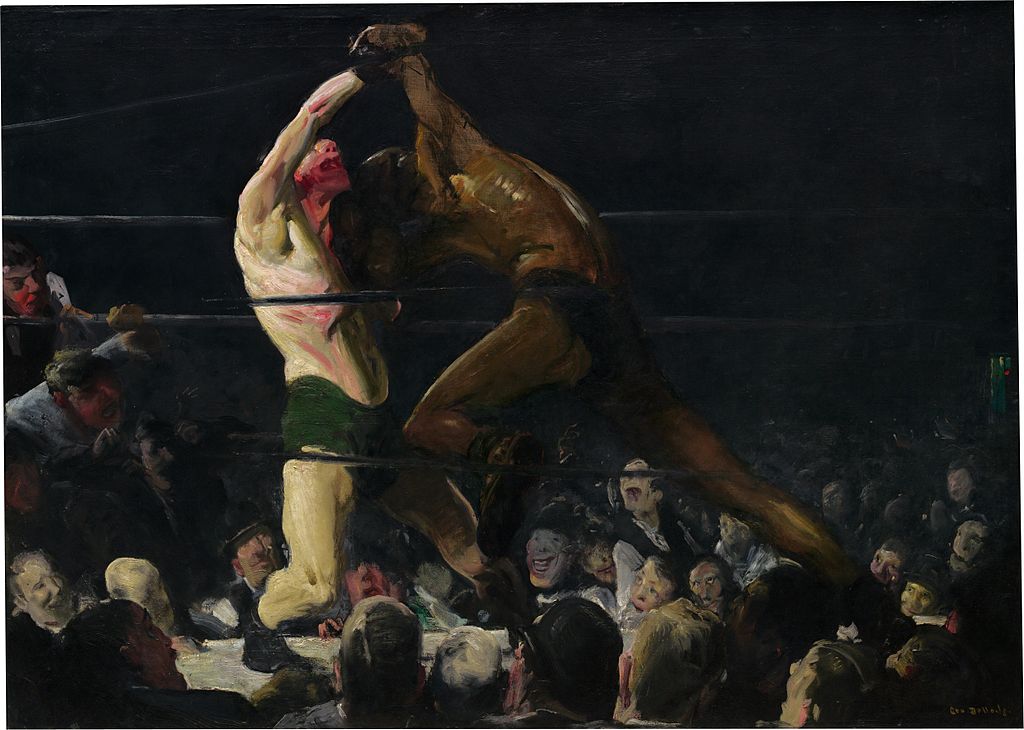

During this time, a legal loophole allowed bouts between members of athletic clubs, so a bar like Sharkey’s would form an “athletic club” and offer one-night memberships to its fighters, hence the painting titled Both Members of this Club. Like Stag and Sharkey’s, long brushstrokes accentuate dynamic movements. However, in this work, open-mouthed, clown-like grins on the spectators harken back to the cartoons Bellows drew for various publications in his college days.

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club, 1909, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Adding to the taboo of the event is that one of the fighters is Black during a time of controversy around segregation in the sport. In his boxing days (1893–1904), club owner Tom Sharkey refused to fight Black athletes. Jack Johnson became the first Black Heavyweight Champion in 1908, and when he beat the white fighter James J. Jeffries in 1910, race riots broke out in several U.S. cities. In 1913, bouts between Black and white fighters were outlawed in New York state.

By the 1920s, new laws took boxing out of underground clubs to mainstream venues. Bellows continued to cover the sport through drawings and lithographs, and these works led to his later boxing canvases.

George Bellows, Introducing John L. Sullivan, 1923, Whitney Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Introducing John L. Sullivan is based on a lithograph Bellows made while covering the Dempsey-Carpentier fight for New York World, and depicts the practice of honoring retired fighters before a bout.

George Bellows, Ringside Seats, 1924, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, USA.

Ringside Seats is based on a drawing done for the short story Chins of the Fathers, published in Collier’s in 1924. However, Collier’s brash cropping caused Bellows to file a lawsuit that was left unresolved after his death.

On assignment for the New York Evening Journal, Bellows was seated in the press box for the Dempsey versus Firpo fight at the Polo Grounds. The wild fight lasted only about four minutes, yet sent the fighters to the mat a combined 11 times. Bellows recorded the dramatic moment when a Firpo blow sent Dempsey flying out of the ring and nearly on top of Bellows.

George Bellows, Dempsey and Firpo, 1924, Whitney Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Just one year after completing Dempsey and Firpo, Bellows died unexpectedly of a ruptured appendix at age 43. Some of the greatest American artists at the time served as pallbearers including Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, and A. Stirling Calder (father of Alexander Calder).

In his short life, George Bellows created some of the most enduring images of 20th-century America. His boxing paintings, a mix of blood and beauty, remain his most thrilling and recognizable.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!