George Washington, the father of the United States, died on December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. Sixteen years later, Washington began posing for a posthumous portrait by the leading neoclassicist sculptor of the day, Antonio Canova.

Thomas Jefferson, who had never met the artist and had never seen the sculptures of the artist in person, recommended Canova for the job. In 1821, the finished marble sculpture was sent to the United States, where it was proudly displayed in the State House in Raleigh, North Carolina. This was the only commission that Canova had ever had in the U.S.

Unfortunately, less than ten years later, a raging fire destroyed the marble sculpture, burning most of it beyond recognition. Only remnants of Canova’s great work survived. By this time, in 1931, both Antonio Canova and Thomas Jefferson were deceased. And so one of the great treasures of early American art was gone forever.

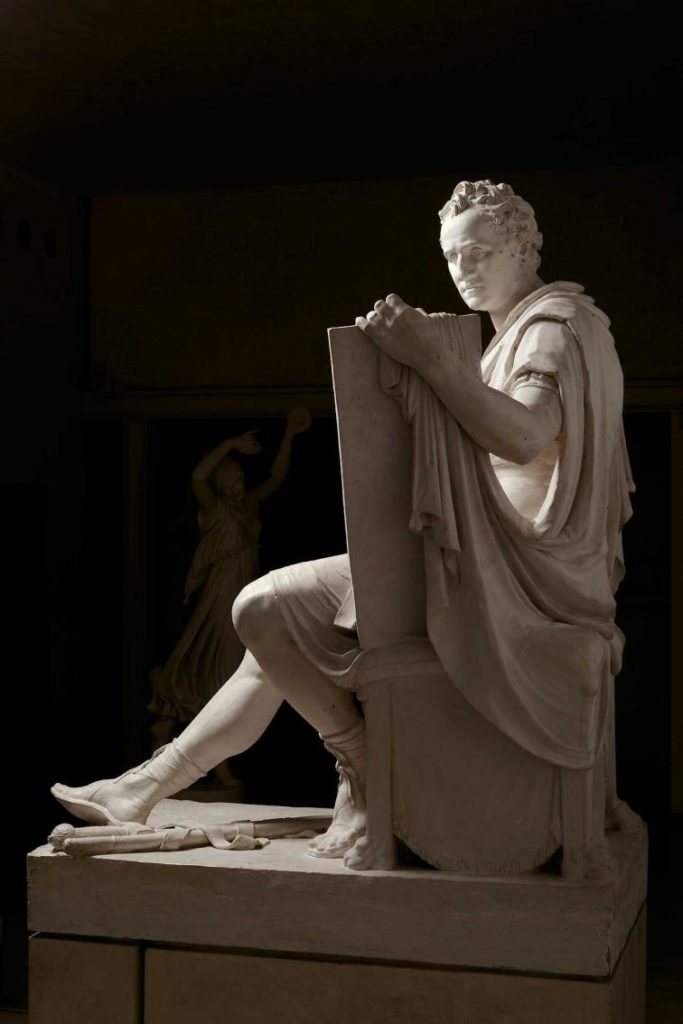

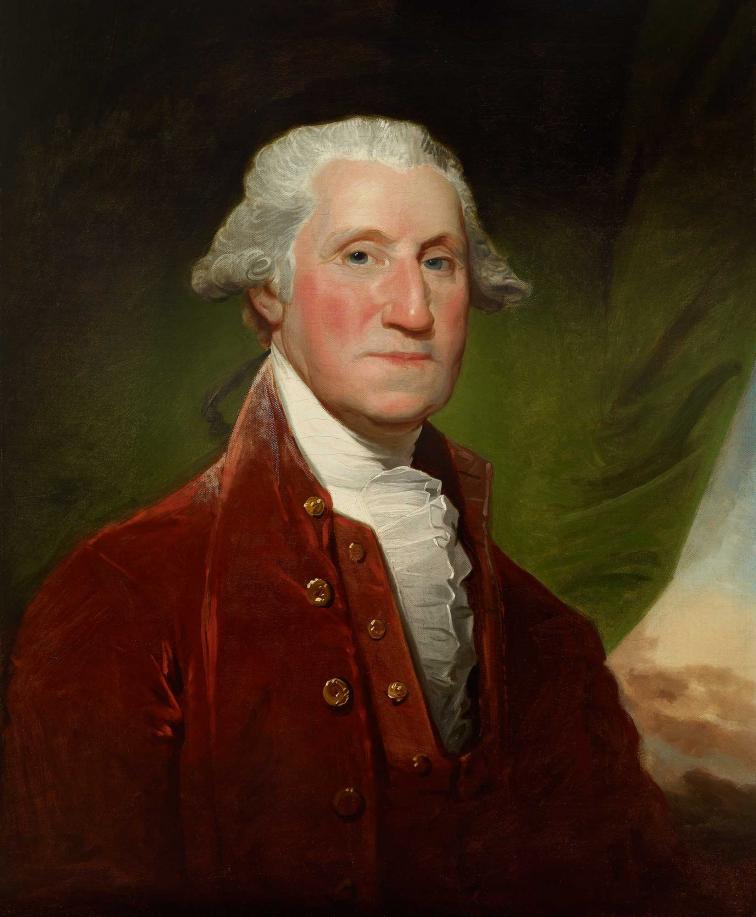

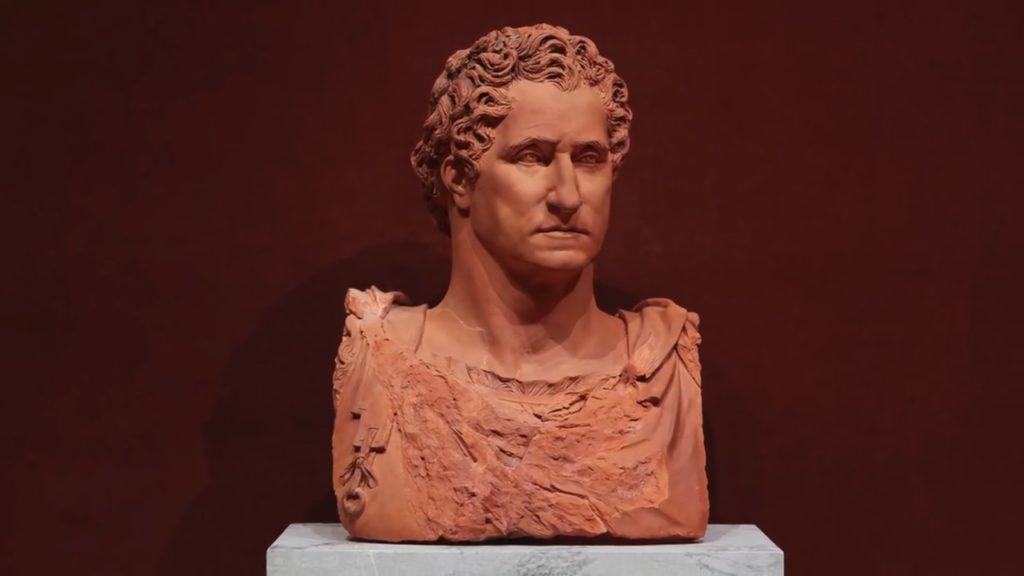

However, Canova had made a “full-size preparatory model” of the statue, called a modello. The modello is the best indication we have of what the finished marble sculpture looked like. The Frick Collection, located on Fifth Avenue in New York City, within a mile of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is displaying this modello, along with preparatory sketches in clay, sculptures by Jean-Antoine Houdon and Giuseppe Ceracchi, a painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, and related drawings, in an exhibit that is on view through September 23, 2018.

The modello is seen in its own room. The Frick explained that it wanted to replicate the feeling of the marble statue being on display in the State House. The ceiling of the State House was lower than the ceiling of this room in the Frick (which is one of the reasons why George Washington is seated instead of standing; a standing statue would have been too big for the State House).

George Washington looks majestic, dressed in Roman clothes, not the George Washington I’ve come to expect from looking at Gilbert Stuart paintings. Canova did not use any of the Gilbert Stuart paintings of George Washington for reference; the painting that is part of this exhibit is there to emphasize this point.

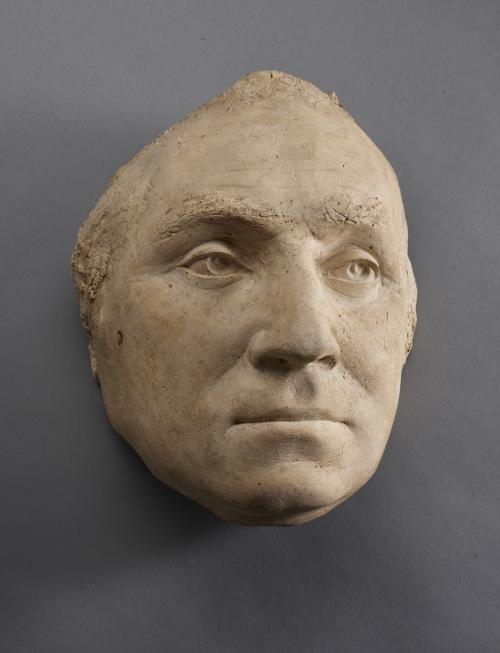

Canova also did not use a sculpture of George Washington’s face by Jean-Antoine Houdon as a reference. Thomas Jefferson believed that a bust by Giuseppe Ceracchi was a better likeness than not only the Houdons, but also the familiar Gilbert Stuart portraits that I’ve associated with Washington since early childhood. Stuart’s version of Washington looks older, less athletic, and overly serious by comparison. Even with this quest for a more perfect likeness, Canova appears to have made Washington’s nose is little longer than it really was shown elsewhere, and a little more Roman, more in keeping with the appearance of the Ceracchi bust than with the Houdon face. Houdon softened Washington’s features more than Ceracchi had.

My first inclination was to look at this modello of George Washington from my 20th or 21st-century perspective. I wanted to walk around the sculpture and watch it move in space. I wanted to see the hand of the artist in the plaster, and I wanted to learn more about George Washington by gazing into his eyes. What does Canova notice about George Washington that I have never seen or felt before?

Taking this approach would have been a mistake. This sculpture was made during the time of neoclassicism. Neoclassicism has a completely different aesthetic from that of my modern sensibility, and to view this model through my modern lens would have done this work of art a grave disservice.

I realized that I needed to travel in the opposite direction. Instead of bringing Canova into the 21st-century kicking and screaming, I needed to bring myself back in time, back to 1821, back to when the influence of Johann Joachim Winckelmann was unrivaled throughout the art world. Winckelmann was, among many things, an art historian whose influential writings captured the spirit and energy of neoclassicism. Neoclassicism strove to recreate ancient Greek art. This was done by the idealization of form and content. A neoclassical artist is more concerned with expressing beauty than he is in accurately portraying the world around him. And the neoclassical artist aspires to idealize more than the beauty of his subject; he wishes to also idealize his subject’s strength of character.

Canova’s George Washington is a man of honor. He is a man who is so noble that he chose to give up his power when he very easily could have held on to it. Washington was a modern day Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, another man who wielded great power, yet also gave it all up to live in retirement on his farm. Cincinnatus was a Roman dictator and he had just won a war. In Washington’s case, he not only gave up the power of the American presidency by refusing to run for a third term in office; years earlier, he had also resigned from the United States army. This is why Washington was dressed as he was, to make the similarity to Cincinnatus that much more apparent. In its description, the Frick quotes the painter John Trumball, who wrote in the year 1784:

Tis a Conduct so novel, so inconceivable to People, who, far from giving up powers they possess, are willing to convulse the Empire to acquire more.

Canova is idealizing George Washington, making him a symbol of what he represents instead of showing him as he really is. Gilbert Stuart never painted George Washington like this. Washington has never looked more powerful or more athletic or more muscular. In the world of 1821, I look at this modello and feel proud that such a great man had been there to lead us. He makes me proud to be an American and to follow his spiritual lead. George Washington is like a Greek god, but without the fatal flaws of a Greek god. Washington is seen preparing his farewell address. As the tablet he is holding indicates, the year is 1796.

Neoclassicism is not supposed to be about emotion, but sometimes emotion sneaks its unassuming head into the conversation anyway. The emotion, in this case, comes from an idea of who George Washington is, and the brilliant decision to convey who he is by comparing him to another great leader from another time. Once I understood what Canova had set out to do, I was moved by this plaster sculpture far more than I would have expected. And suddenly, the neoclassical perspective was the perfect approach to express a profound truth about one of the most fascinating and revered people in the brief history of the United States.

Find out more: