Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

15 November 2024 min Read

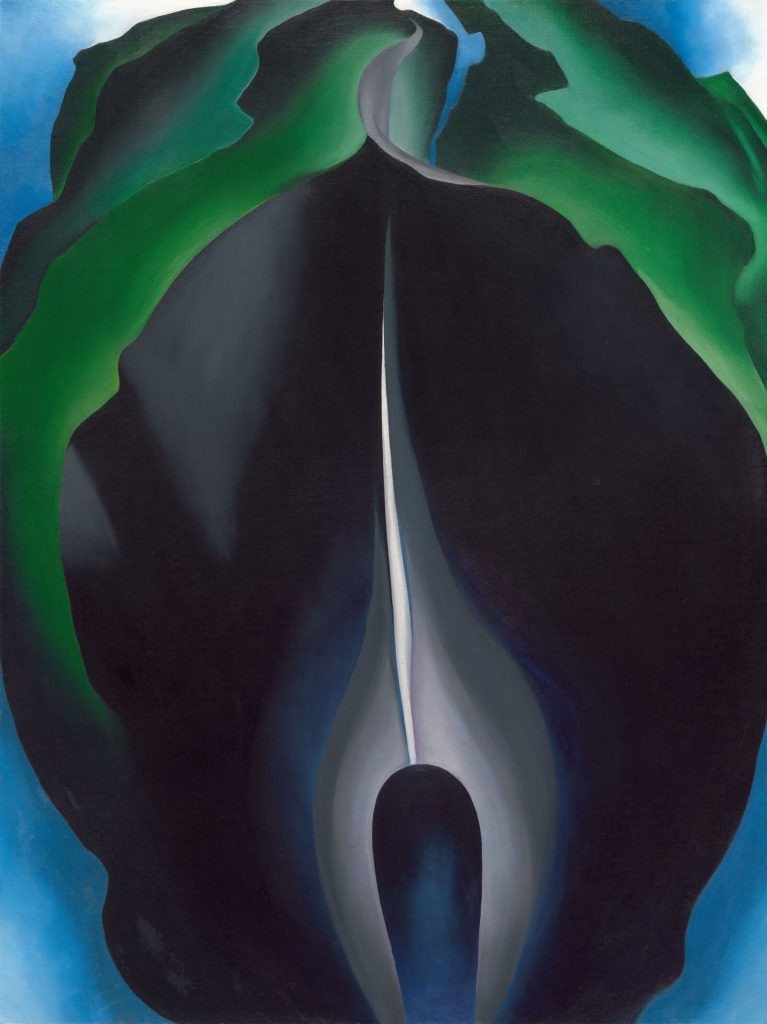

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the greatest female artists of the early 20th century. She could also be considered the mother of American Modernism. She was a pioneer in reducing subjects to their purest colors and forms to heighten their expressive power. Georgia O’Keeffe’s most famous subjects are her enlarged images of flowers. Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV is one of her most famous paintings exploring this floral theme.

Georgia O’Keeffe began painting flowers during the 1920s. She was encouraged and promoted by her husband, the famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz. While Stieglitz’s art-world connections gained O’Keeffe initial artistic exposure, it was through her own talents that gained her long-term recognition as an established artist. Georgia O’Keeffe began painting flowers after admiring some paintings by Henri Fantin-Latour, a 19th-century French painter famous for his floral still lifes. However, instead of simply emulating his style and subjects, Georgia O’Keeffe pushed herself to be bolder in scale and color. Therefore, O’Keeffe created larger-scaled images of flowers with a more saturated color palette.

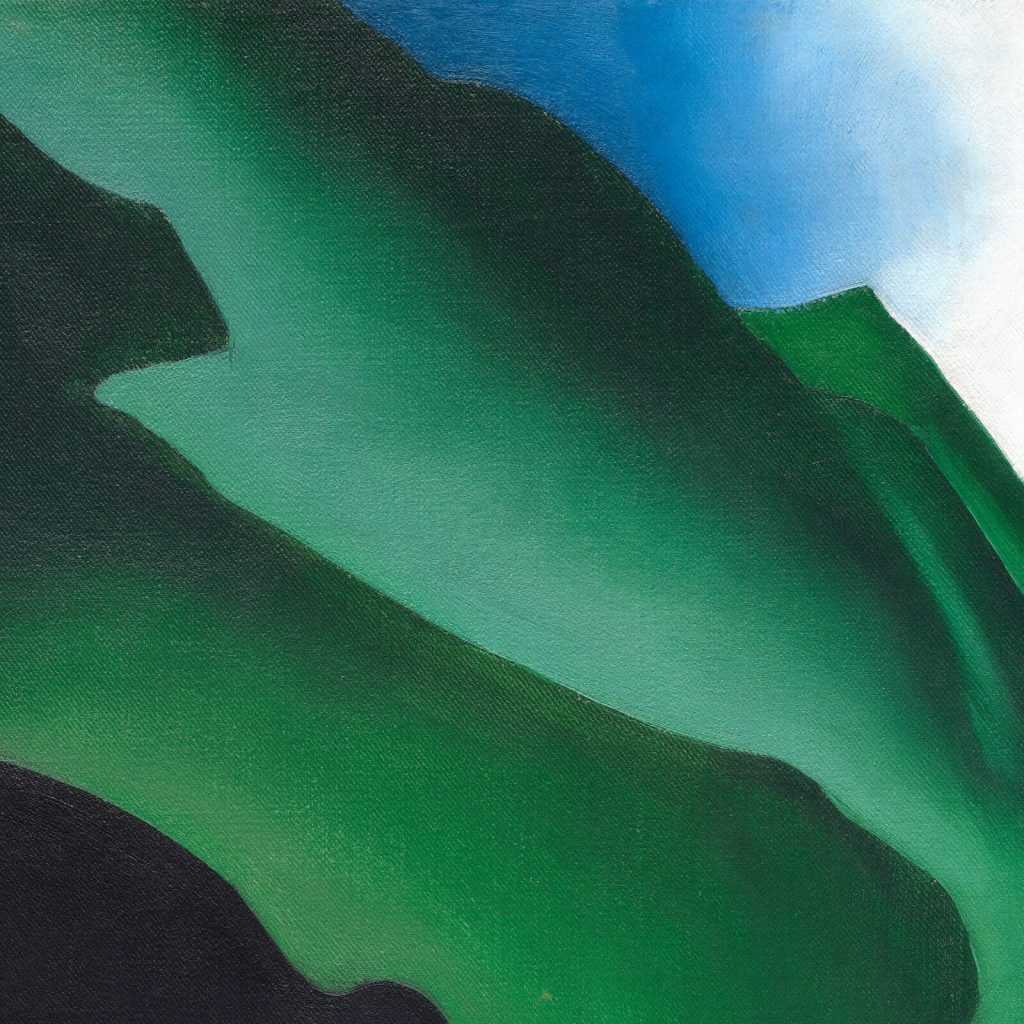

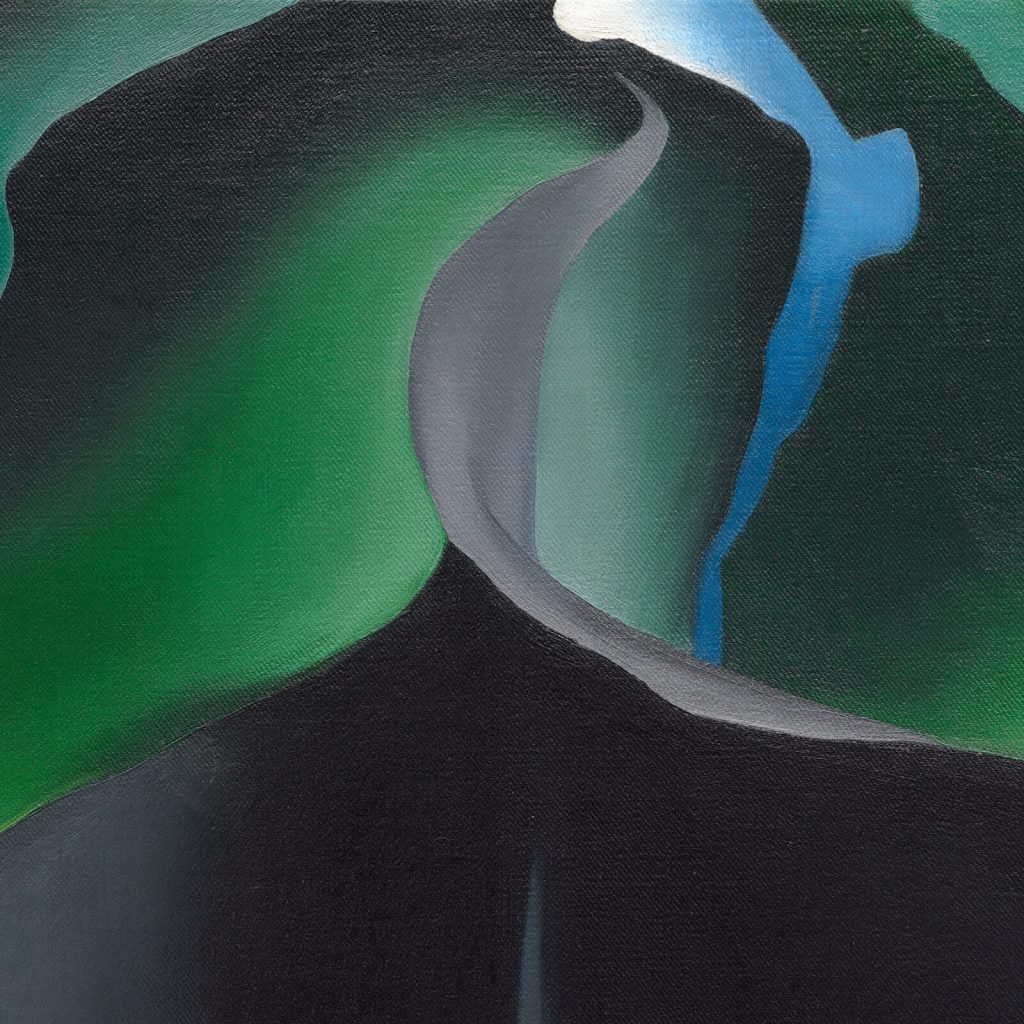

Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV is one of her most famous examples. It captures a close-up lateral view of the interior of a jack-in-the-pulpit or Arisaema triphyllum. The flower is unusual compared to most garden variety flowers because it features a spadix and a spathe. The spadix, or jack, is featured at the bottom center of Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV. A spadix is a type of flower spike covered in small flowers on a stem. In the painting, the spadix is reduced to a blackish-blue finger-like form contrasting against a cream background. The spathe of a jack-in-the-pulpit is essentially a hood-like part of the flower. It is informally called a pulpit. The spathe shields the spadix with umbrella-like protection. The underside of the spathe closest to the spadix typically has colors and/or stripes. In Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV, O’Keeffe paints the spathe as a deep purple, almost black, in certain areas. It violently contrasts with the creamy center and the surrounding green foliage.

Many previous artists such as Rachel Ruysch, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri Fantin-Latour became famous through their representations of flowers. Their still lifes are equally different from each other through their handling of colors, lines, and shapes; but they are all similar in being marginally life-size and maintaining realistic dimensions. Georgia O’Keeffe explodes the size of her flowers. Her flowers are over life-size. They are massive. Unframed Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV measures 102 cm. (40 in.) high and 76 cm. (30 in.) wide. The flowerhead of a large jack-in-the-pulpit can only reach up to 10 cm. in height. This means that O’Keeffe’s Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV is 10 times the actual size of the botanical inspiration. Therefore O’Keeffe enlarges her subjects to a monumental scale, which allows her to explore the drama, texture, and complexity of the flowers’ forms.

When Georgia O’Keeffe created Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV in 1930, she was visiting Lake George in New York state. We can only guess as to the origin of the bright blue background featured in Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV. Some art historians theorize it might represent the water of Lake George, while others believe it might be a bright blue sky. Regardless of what the blue background represents, it is clearly featured at the four corners of the painting. It contrasts sharply and vibrantly with the bold purples of the lower canvas, and with the bold greens of the upper canvas. It creates a defined silhouette for the flower, and enhances the bold presence of Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s flower paintings have been a source of debate ever since they were created. Many people have said that her flowers represent female sexuality through their visual illusions of female genitals. However, many people refute this Freudian interpretation based on O’Keeffe’s own opposition to such claims. During her lifetime O’Keeffe repeatedly denied that her flowers had any overt or covert sexual content. She simply wanted to explore the drama of flowers’ structures and focus on their shapes, textures, and rhythms. Will the art world and the general public ever stop looking for genitals in art? Are we that obsessed with sex?

Georgia O’Keeffe painted Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV as a part of her artistic explorations. She sought to see poetry in nature and beauty in geometry. While her flowers do not have the visual explosions of Wassily Kandinsky or the rectilinear absolutes of Piet Mondrian, they do almost border on the abstract. Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV, like many of her other flower paintings, uses bold scale, reduced colour, and echoed rhythm. Hence, Georgia O’Keeffe aimed to not merely duplicate the flowers she painted. She aimed to clarify their visual meaning. Therefore, Georgia O’Keeffe could be considered the mother of American Modernism and Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV as one of her greatest works to support this title.

Wendy Beckett and Patricia Wright. Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

Victoria Charles, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006. ISBN 9780760772164.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Georgia O’Keeffe.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

Robert Torchia. “Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV.” Collection. National Gallery of Art, September 29, 2016.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!