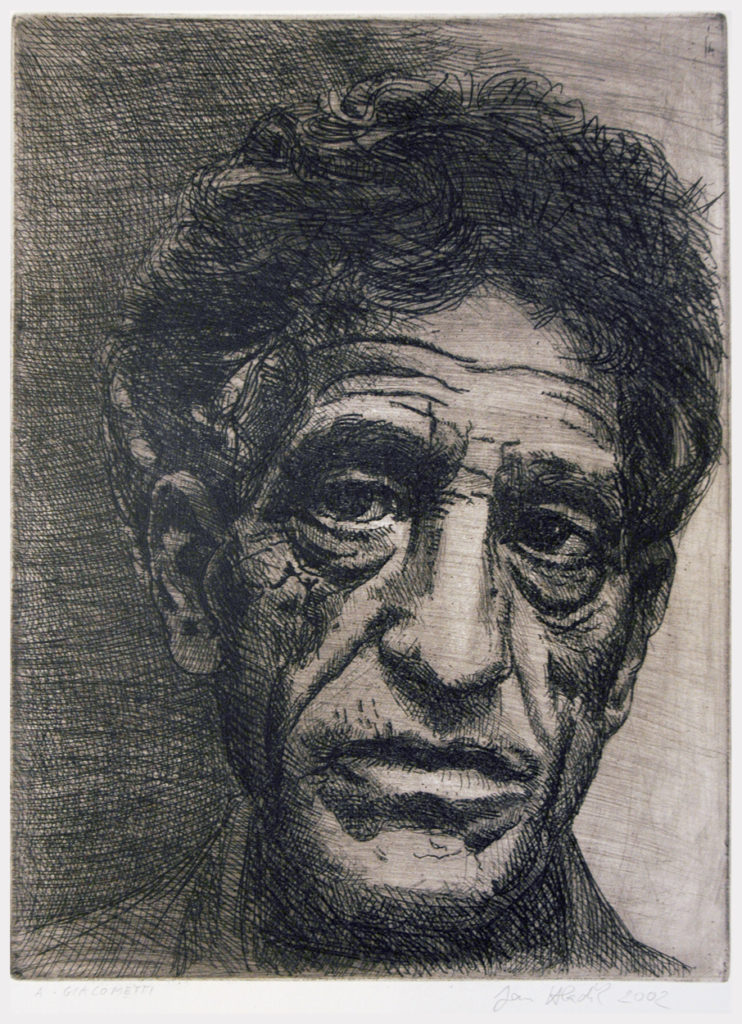

Near the end of the Giacometti exhibit in the Guggenheim Museum in New York City is a video of the artist being interviewed. Giacometti’s hair is at once combed and struggling to break free of the influence of the comb. His glasses are black and thick. His face is pensive and wrinkled, with many crevices and bumps and indentations along the way. Giacometti is wearing a gray jacket over a black shirt. In one part of the video, he is modeling a head in clay, a greenish-gray clay, with a delicate, yet firm, touch.

Giacometti is talking about the dilemma he faces as an artist.

The closer I come to this head, the more it eludes me, he says. And the distance between us increases, which forces me to come nearer and nearer to it.

The artist looks as if he is in deep conversation, not with the interviewer or with the audience, but with the beautiful clay head, he is working on. He is holding his metal tool with his left hand while attempting to smooth the socket of one of the eyes with the thumb of his right hand.

If someone were to pose for me for a thousand years, in a thousand years I would say to that person, it’s still all wrong, but I’m getting a little nearer.

This helps to explain why the Giacometti drawings and sculptures (especially the sculptures) are so moving, and why I am so drawn to them. The artist is engaging in a process, and I, as an observer, am an intimate part of this process. Giacometti painted and sculpted the same people over and over, constantly striving to find reality, believing he will never succeed, yet steadfast in his determination to be on this journey anyway, growing and learning and observing, doing what he loves to do.

Each sculpture and each painting is not an end in and of itself. Each work of art is part of something bigger, something beyond his control. How many of us, faced with failure and potential frustration, would shrug our shoulders and move on to something else? Or move on to nothing at all? Giacometti’s approach makes me think. When I meet an interesting person in my life, how well can I get to know this person? In the beginning, I hope to find some common ground, some similar experiences, and feelings upon which to base a relationship. Throughout this process, I tend to jump to many conclusions, conclusions that may be based more on my perspective of the world than on that of my companion’s. Yet, if I continue to struggle through misunderstandings and differences of opinion and other obstacles too numerous to mention, after months and years, I will still have failed to really get to know this person, but I will be closer than I was when I started, and the journey will have been just as fulfilling as the end result, which is beyond my reach.

I can watch the video of Giacometti over and over. I can look at his artwork, especially his later existentialist period, and see and feel something slightly different from what I saw and felt before. I can look at the same sculpture over and over as well.

This exhibition brings together the many phases of Giacometti’s work—his cubist phase, his surrealist phase, and his existentialist phase. All three phases are wonderful, but the existentialist period is the one that I think about the most. I wondered why, at one point, the figures were so thin. Are they representative of the prisoners from concentration camps from World War II? Is the isolation of the figures connected to the tenets of existentialism, the belief that existence precedes essence, and that we, as individuals, are able to define our own essence and live our lives based on those beliefs?

My answer is no, but I am open to being persuaded otherwise.

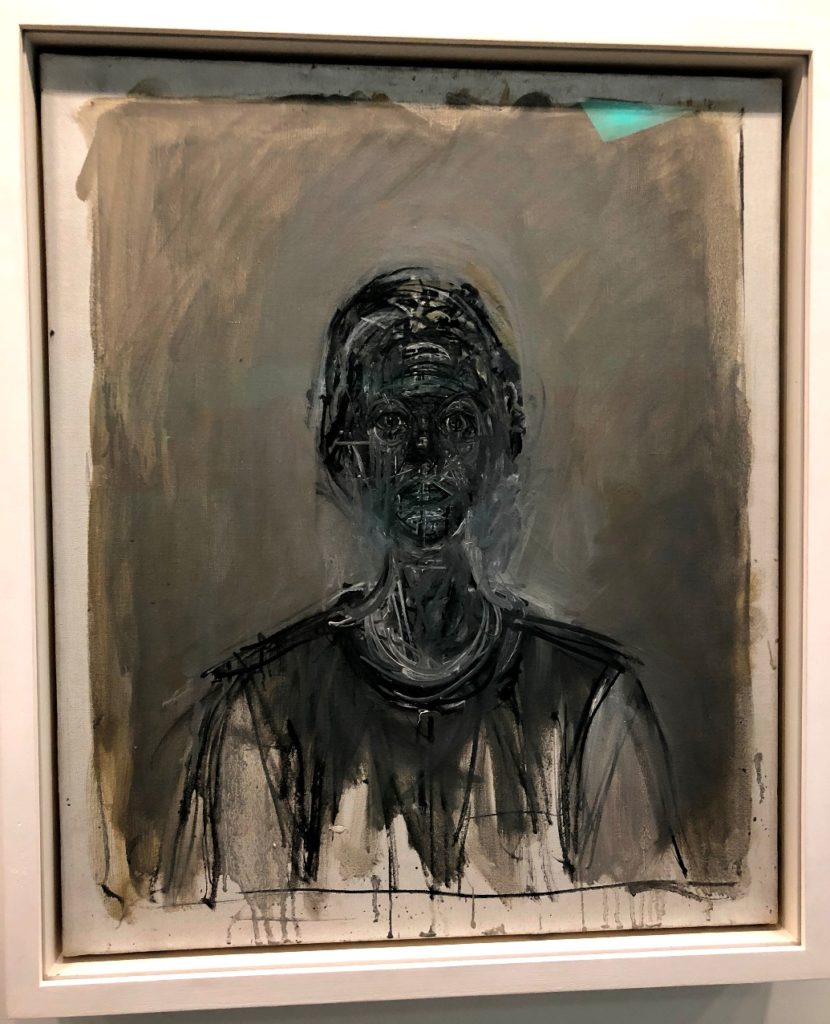

The exhibit begins with a sculpture of ‘Black Annette’ (Annette Noire) from 1962. Annette Arm was Giacometti’s wife. She posed for him every day. This sculpture was made four years before the death of the artist, and its description provides some important clues into the workings of Giacometti’s mind:

Giacometti’s portraits, either painted or sculpted, are the translation of the sitter as an implacable otherness that can never be grasped in its entirety. Expressionless portraits, such as this strictly frontal work with wide eyes gazing straight ahead, are the receptacle of the spectator’s scrutiny. Giacometti declared: I cannot simultaneously see the eyes, the hands, and the feet of the person standing two or three yards in front of me, but the only part that I do look at entails a sensation of the existence of everything.

This quote explains a lot, while also raising many questions. While the artist is standing nine feet away from his model, I find myself getting as close to each work of art as possible. I do this to more fully appreciate the texture of the surface, especially of the sculptures, but the closer I get, the further removed I am from Giacometti’s vision because when I am gazing at the head of a sculpture from two feet away, I am unaware of the rest of the body and I am not seeing the figure as a whole. But then again, I am not required to adhere to someone else’s vision. I enjoy looking at art from up close and then stepping back and seeing how that piece of art has changed, assuming it has.

Black Annette is monochrome. She is looking straight at me, fully frontal, with her eyes wide open and her head ever so slightly looking up. Annette is vulnerable, her arms by her side, and she appears to be thinking or feeling something profound. Giacometti has chosen to paint Annette down to her torso, cutting off more than half her body, and I wonder whether I am able to sense “the sensation of everything” that Giacometti describes.

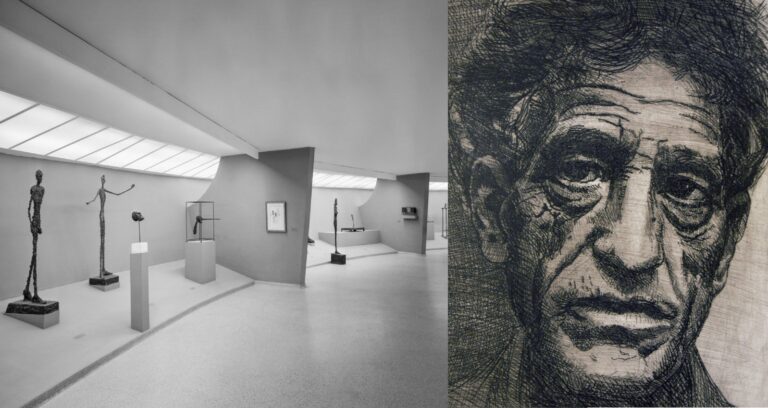

The painting of Annette is followed by three sculptures that were inspired by a proposal for “a competition for a monument to be installed in the plaza of the new Chase Manhattan Bank skyscraper, near Wall Street in Lower Manhattan.” One sculpture is in motion, taking a step forward. Another is of a similar figure, but standing straight and not moving. The third is a bust of a head with an elongated neck. The spacing of these three sculptures adds to the atmosphere, and to the movement of the piece.

The exhibit is a large and comprehensive one, spiraling around the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum over and over again. Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Guggenheim, giving it the unique quality of not having divisions in the usual sense. Normally one room would be slightly cut off from the next, with its own beginning and end. In the Guggenheim, there are no rooms in the usual sense. This creates a flow, going from one area to another.

One of my favorite surrealist sculptures from the exhibit is ‘Spoon Woman’ (Femme cuillère), made in plaster in 1927. Without arms, without legs, and without facial features, Giacometti is able to create, what appears to me, to be the essence of a woman. Another wonderful surrealist sculpture is ‘Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object)’ (Mains tenant le vide [Objet invisible]) a bronze cast of a sculpture from 1934. This work is described as an icon of Giacometti’s surrealist period. The description on the museum wall notes that this was the last work he composed while associated with the group. The rectangular support and the unseen void made me think about this piece long after I had left the museum.

The exhibit is simply called ‘Giacometti.’ It opened on June 8 and will close on September 12. The Guggenheim has had an intimate relationship with Giacometti through the years, and this comprehensive exhibit is yet another example of this relationship. The museum had had another retrospective of Giacometti back in 1974, eight years after the artist’s death. I left the exhibit with many questions, but also an unabated eagerness to search for some of the answers.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0892075384″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/41yU8uyy0EL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”116″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”2080203797″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/51VR2552BSML.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”100″]