A woman who walks. That’s what Gradiva (the name of an anonymous woman from an antique bas-relief) means, as given by a fictional character from a novella by Wilhelm Jensen. In other words, it’s an invented name for an unknown woman in stone. However, because of Freud, the figure has become a myth in her own right.

Jensen

The bas-relief is part of a composition showing three women moving from the right (the third woman is kept at Uffizi in Florence). They are associated with three Agraulides sisters, deities of dew. In Wilhelm Jensen’s Gradiva, A Pompeian Fantasy (1903) the protagonist, who is an archaeologist fascinated by the relief he sees, names the figure Gradiva after the Roman god of war, Mars Gradivus. He’s so bedazzled that he meets the woman among the ruins of Pompeii, but he’s unsure whether or not he is dreaming.

Freud

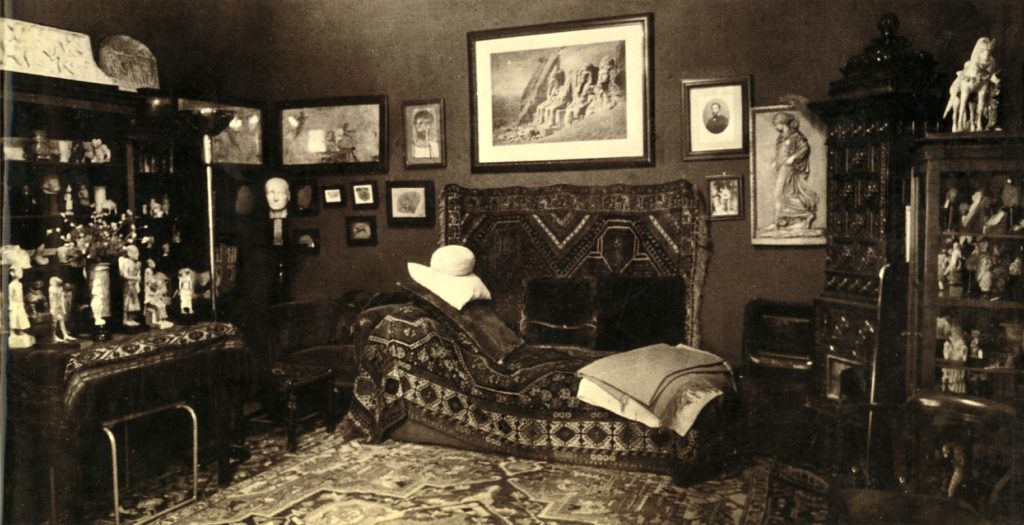

The story was brought to the attention of Sigmund Freud by Carl Gustav Jung. In his study Delusion and Dream in Jensen’s “Gradiva” (1906), which was one of his first analyses of a literary piece, he examined the novella as though it were a psychiatric case. He did this in order to explain how external stimuli may sometimes bring the most hidden psychic tensions to the surface. When Freud visited Rome in 1907, he wrote to his wife Martha Bernays

“I saw today a dear familiar face”

and he bought a cast of this relief. Upon his return, he hung it on the wall of his study at Bergasse 19, Vienna near the famous couch.

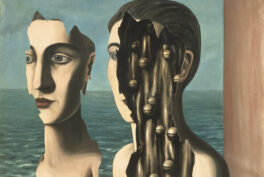

The Surrealists

Nadeau Maurice wrote in A History of Surrealism in 1965 that Gradiva ‘the woman who walks through walls’ was the muse of the Surrealists. This is because she was a character on the verge of mythology, dream, and psychoanalysis. Therefore she was a perfect fit for all those exploring the subconscious and fantasy, especially the sexual fantasy.

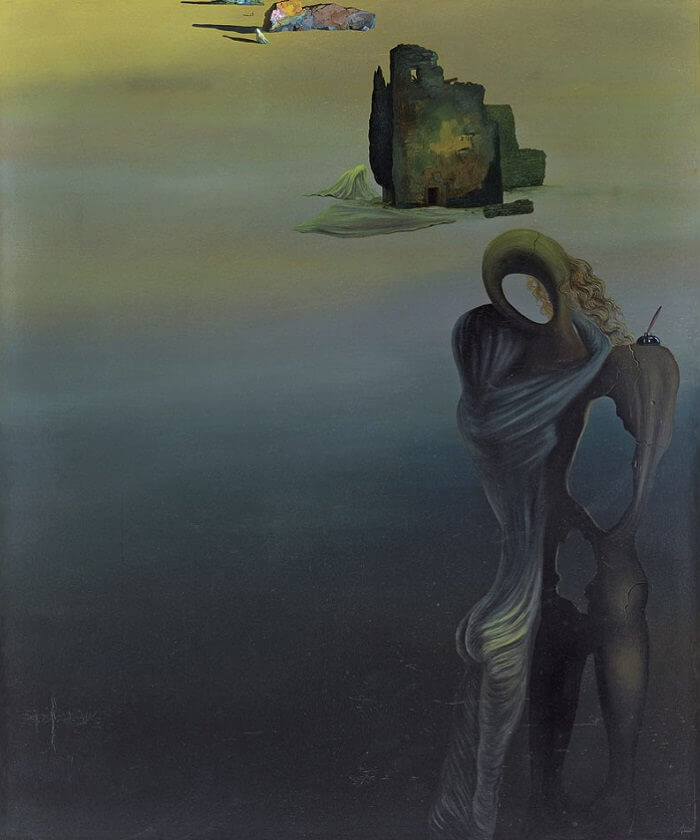

Salvador Dalì found an incarnation of Gradiva in his future wife, Gala. He met her shortly after having read Freud’s study and having become fascinated by Gradiva. Gala served as a model for him in a few representations of Gradiva. He even called her Gradiva, as exemplified in his autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, published in 1942:

To Gala–Gradiva, the one who advances. (…) She was destined to be my Gradiva, ‘she who advances,’ my victory, my wife.

Dalì’s interest in the feminine and female body did not just lead to a broad body of painting though. It also had an influence on the conception of André Breton’s Parisian art gallery which he named, yes, you guessed it, Gradiva.

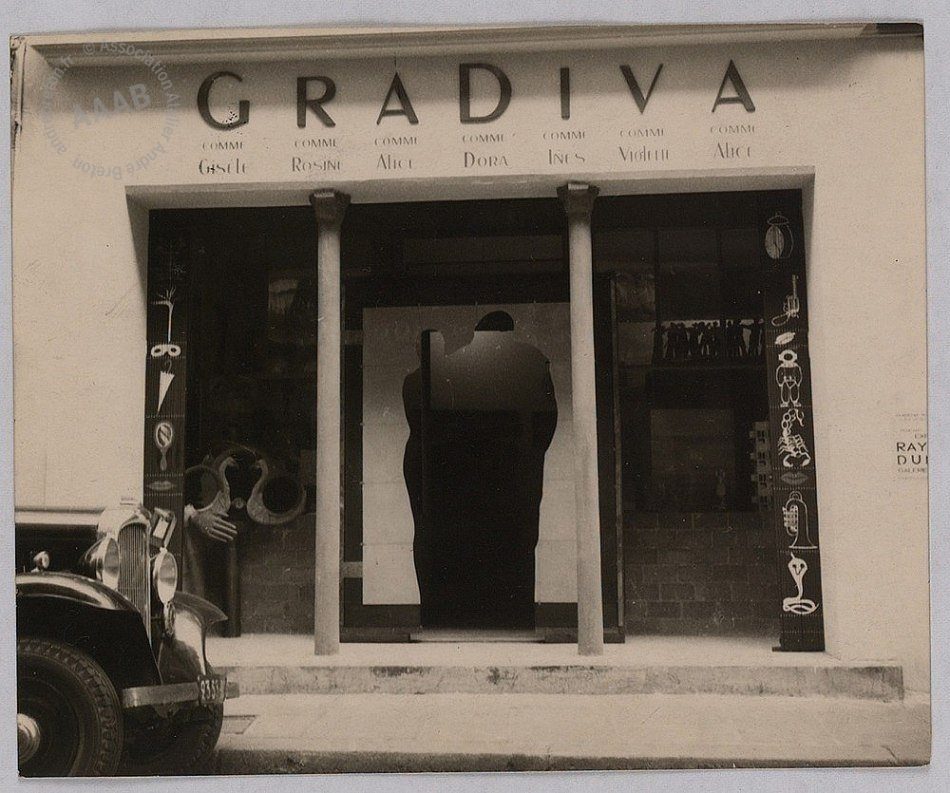

Duchamp

In 1937 André Breton opened the doors to the gallery Gradiva. He gave the name a yet another meaning, as its letters stood also for the initials of women who were muses of the Surrealists (Gisèle, Rosine, Alice, Dora, Iñes, Violette, Alice). He also accentuated the word ‘Diva’ in the lettering on the façade by capitalizing the “D”.

Breton, Association Atelier André Breton

The door, designed by Marcel Duchamp, took the form of an incised silhouette, this time not of a walking woman but of a couple, closely entwined and standing. Maybe because he wanted the visitor to take a step to get closer to Gradiva, not just to watch her walk and dream about her.