By the time you read this, the Grant Wood exhibit in the Whitney Museum in New York City will be over. ‘American Gothic’ will be heading back to its home, the Art Institute of Chicago. Why did I wait until the last weekend possible to see this iconic painting and this retrospective exhibit?

Grant Wood was never one of my favorites. I prefer bold brushstrokes that can be seen from a distance. The brushstrokes in a Grant Wood painting are not noticeable, and this is by design.

Wood’s paintings from the 1920s are good paintings, but I am not moved by them. The compositions are nice and the painting technique is highly accomplished and sophisticated. He is able to paint light. The colors are accurate and in harmony. He draws well. He is able to model forms, going from dark to light, turning his edges with ease. However, these paintings will not stay with me once I leave this room.

But then, when I walked into the next room and saw ‘American Gothic’ from a distance, everything changed. To be more precise, ‘American Gothic’ did not change my mood; it was the other portraits in the room that caught me by surprise. These portraits are unique. ‘Victorian Survival’ depicts a Victorian woman whose stiff posture and possibly even more rigid state of mind has found a companion even stiffer than she is in the telephone that is almost hidden from view. A relic by today’s standards, that telephone was considered to be a glowing example of the technology of the time, similar to today’s iPhone 10. The other portraits, including one of the artist’s mother, are wonderful as well.

The description on the wall provides some interesting information about the paintings in this room:

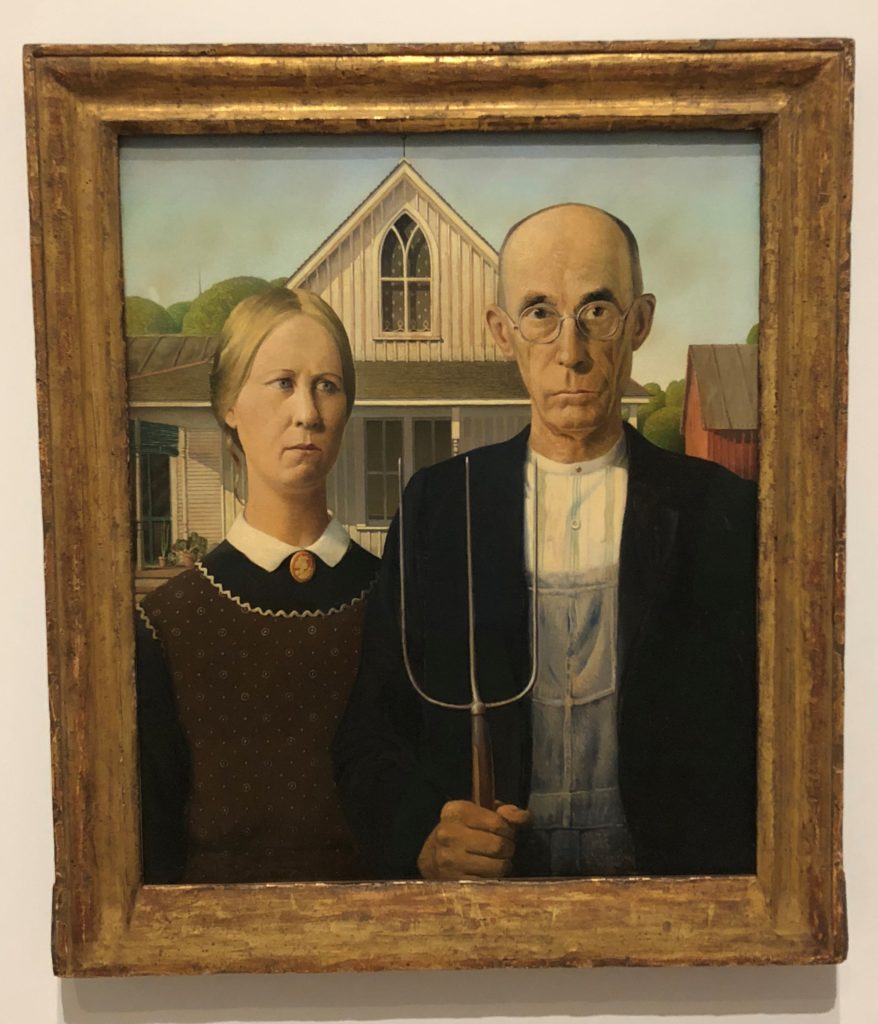

By the late 1920s, Wood had come to believe that the emergence of a rich American culture depended on artists breaking free of European influence and expressing the specific character of their own regions…In Europe, he had admired Northern Renaissance painting by artists such as Hans Memling and Albrecht Dürer. By the time he painted American Gothic in 1930, he had concluded that the hard-edged precision and meticulous detail in their art could be used to convey a distinctly American quality, especially suggestive of the Midwest.

The “hard-edge precision” is what makes these portraits so special. The contours of the heads have no lost and found edges and because of this, the heads look like cutouts. At the same time, these heads are rendered with so much detail, with realism and character. My eye is drawn to each head first, and then to the rest of the composition. The negative shapes of the paintings are beautiful.

I really enjoyed looking at ‘American Gothic.’ It is such an icon of twentieth-century art, and so different from many of the other icons of the time, especially in the United States. (I think ‘American Gothic’ would feel at home next to the paintings of Otto Dix and his German contemporaries, however.) I enjoy Grant Wood’s ironic and subtle sense of humor. Whether the two people are his sister and the family dentist, a husband and wife, or a father and daughter, I am struck by how miserable and content they are, and how resigned they are to the misery of their day-to-day existence. The three-pronged pitchfork, with its sharp edges pointing upward, creates a wary expression from the stoic, yet an apprehensive woman. These two people appear joined at the hip, yet show no outward signs of affection for one another. She looks in his direction, but not at him. Maybe she’s looking at the pitchfork. The man is looking straight ahead but is making no eye contact with the viewer. Neither of them wants to be anywhere else; neither can imagine a better world or a life more fulfilling than the one in which they are trapped.

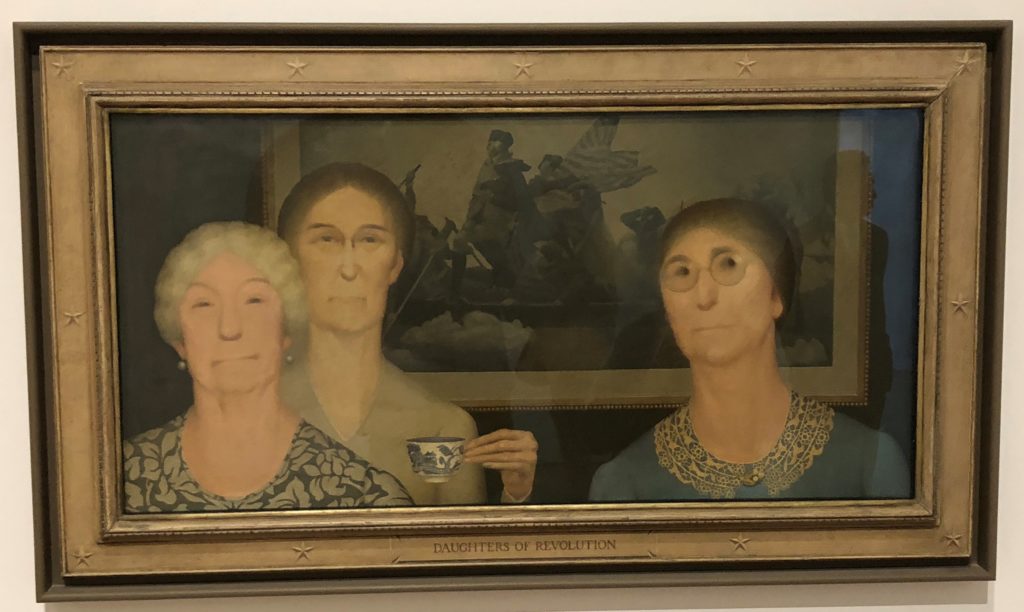

In the next room is one of the best paintings in the exhibition—‘Daughters of Revolution,’ from 1932. The description reads, in part:

In this painting Wood aimed to ridicule the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) for their claims to nobility based on ancestry, which he saw as antithetical to their celebration of democracy. The artist painted three of the group’s members in front of a reproduction of Emanuel Leutze’s painting of General George Washington crossing the Delaware River, contrasting the future president’s dynamism and bravery with the Daughters’ stiff poses, contemptuous expressions, and the inconsequential action of raising a teacup.

Grant Wood’s wry sense of humor was in peak form in this painting. The portraits of these three women make me want to laugh out loud. One can easily understand why the DAR didn’t respond well to this painting.

I’m glad I got to see this exhibition before it ended. I left the Whitney with more of an appreciation for Grant Wood than I had when I walked in, and I wish I could revisit these paintings in a couple of weeks to see what else I can learn from them.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0300232845″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/51x7ZE0bfML.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”121″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1572153571″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/51bvjBlyVJL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”116″]