12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

For many, photography is merely a sophisticated way of immortalizing the current and carrying that frozen moment – which is impossible to recreate – onward to the vastness of time. Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari (Έλλη Σουγιουλτζόγλου-Σεραϊδάρη), known as Nelly, a Greek photographer, not only captured mesmerizing shots throughout her lifetime, but she was also able to brilliantly amalgamate them with the unmatched beauty and grandeur of ancient Greek aesthetics.

Through her Neoclassical approach to photography, Nelly enhanced the modern subjects by infusing them with the idealized Hellenic manner, which ultimately contributed to the revival of Neoclassicism. Without further ado, let’s take a look at her story!

Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari was born in Aidini (Aydın) in Ottoman Empire in 1899. Later in her career, Elli chose to identify herself as Nelly, and from here on out, that is how I will refer to her. Aidini was a small city close to Smyrni (İzmir). Both cities had a significant number of Asia Minor Greeks who were native to the region. When Nelly was around 19 years old, the Greco-Turkish war broke out, and she settled in Smyrni with her family. Given the harshness of the circumstances, Nelly left for Germany to study. It was 1922 when she got the news that the Greek population of Smyrni had to leave their homes behind and settle on the mainland of Greece because of the war. Her family settled in Athens, and Nelly was able to visit them for the first time in 1924.

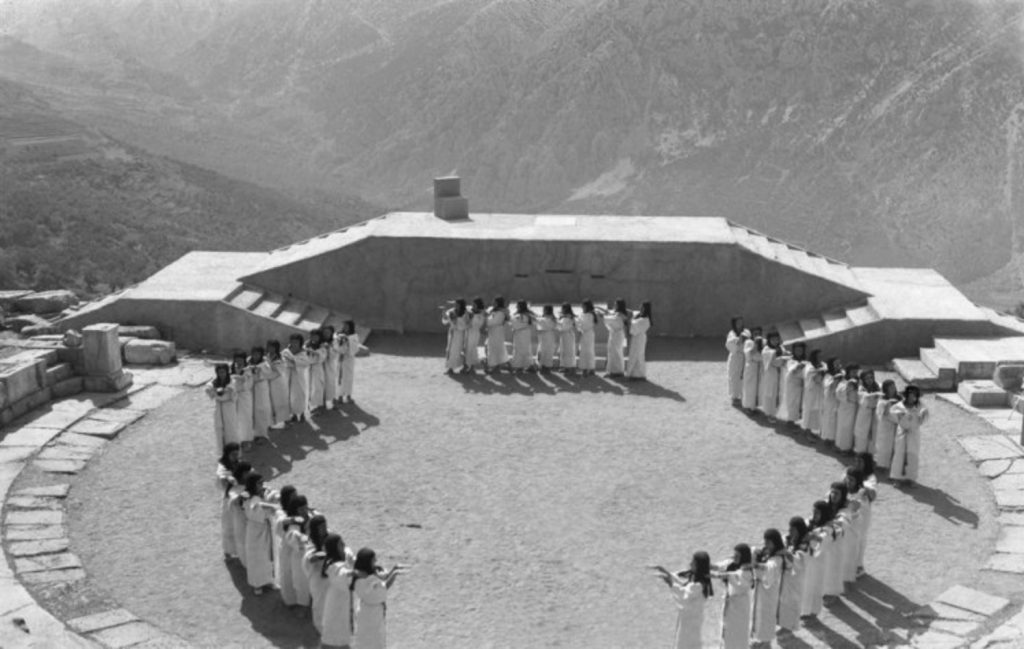

When she first went to Dresden, Germany, she was planning to study visual arts, specifically painting, yet, life steered her on a different path. Under the guidance of Hugo Erfurth and Franz Fiedler, Nelly mastered the art of photography and opened a photography studio on Ermous Street in Athens to apply what she learned during her studies, as well as share her vision. She worked for the Ministry of Culture and collaborated with prominent figures such as Angelos Sikelianos and Dimitrios Kambouroglou.

From 1924 to 1939, Nelly explored the beauty of Greece, portraying the daily lives of Greek people. She focused a great deal on the Asia Minor Greeks who were living in the slums of Athens. Their sufferings, caused by a forced displacement, pushed Nelly to depict their tales since she was also affected. On the other hand, as a photographer, she put great emphasis on her relationship with archaeological sites and ancient structures. Antiquity always fascinated her, and she demonstrated this fascination through her frames in captivating ways.

In 1939, with the encouragement of the Ministry of Tourism, Nelly flew to the United States of America with her husband and musician, Angelos Seraidaris. Her task was to coordinate the aesthetic route of the Greek pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. However, when World War II broke out, they decided to stay for “a bit.” During this time, she opened a new studio on 57th Street. They lived in New York for a total of 27 years. During that period, she established strong bonds with the Greek diaspora as well as prominent American figures, such as Eleanor Roosevelt.

Nelly organized many exhibitions. Her works were purchased by institutions such as The Metropolitan Museum. The couple finally returned to Nea Smyrni, Greece in 1966, and Nelly stopped working actively. In 1985, she generously donated all of her archives and cameras to the Benaki Museum in Athens. Until her death in 1998, she was awarded honorary titles and medals, such as the Order of the Phoenix from the Hellenic Republic.

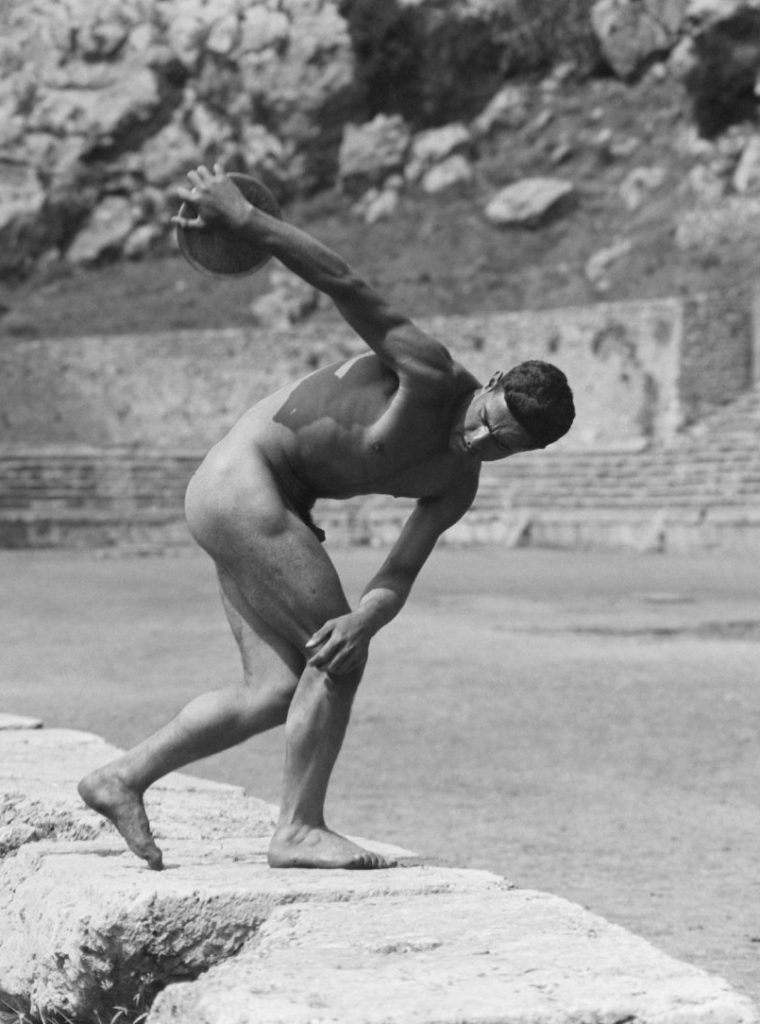

Until the end of her career, the teachings that she was exposed to during her years in Germany were always present in her works. She too was influenced by the same approach adopted by her mentors, which was called pictorialism – an artistic attitude that prioritizes the beauty of the subject and its relation with the setting. For Nelly, the act of documenting an occurrence or a moment was never enough, she desired them to be visually graceful even when she photographed individuals who were in gloomy situations due to the harshness of life.

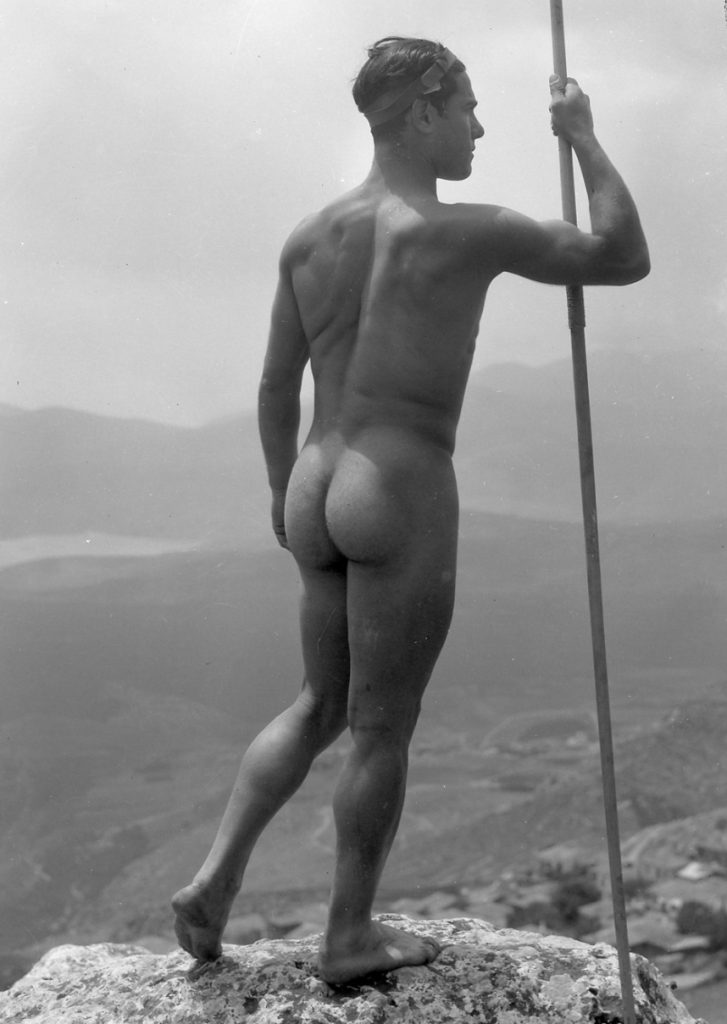

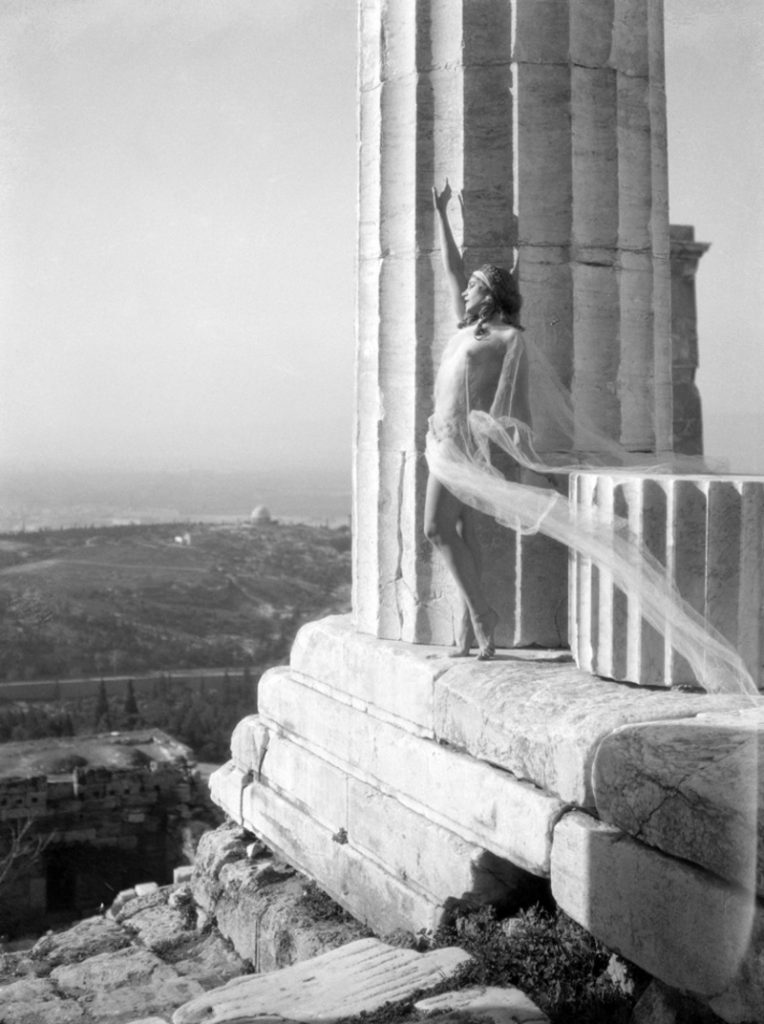

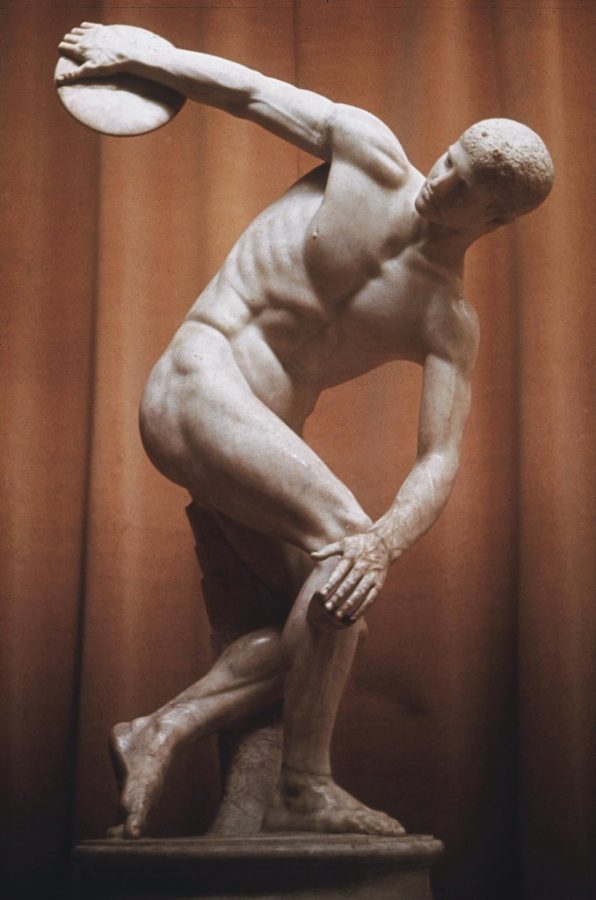

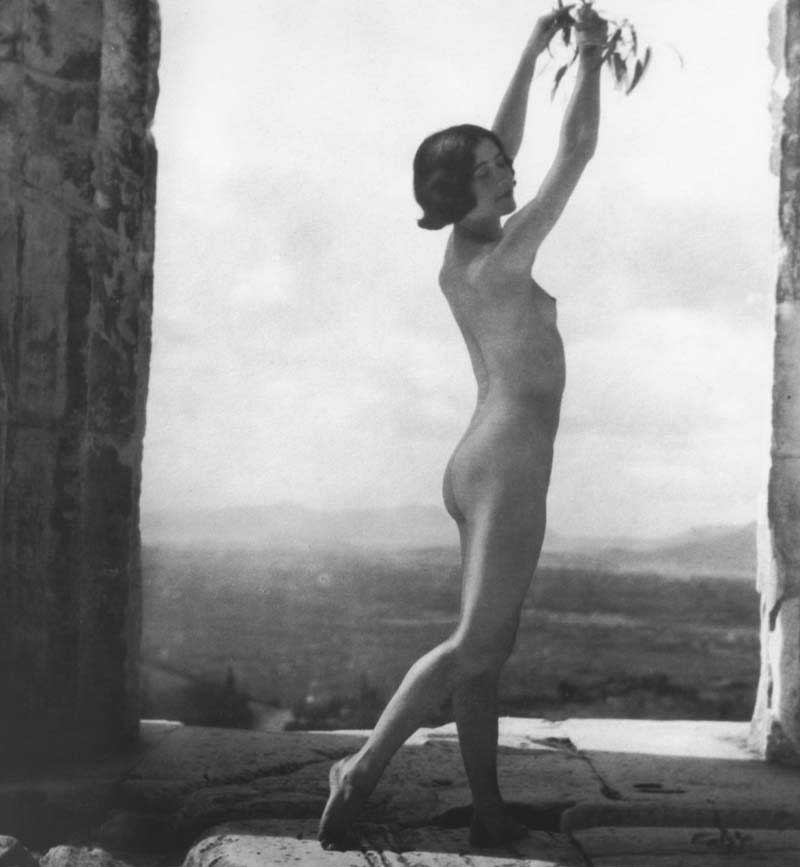

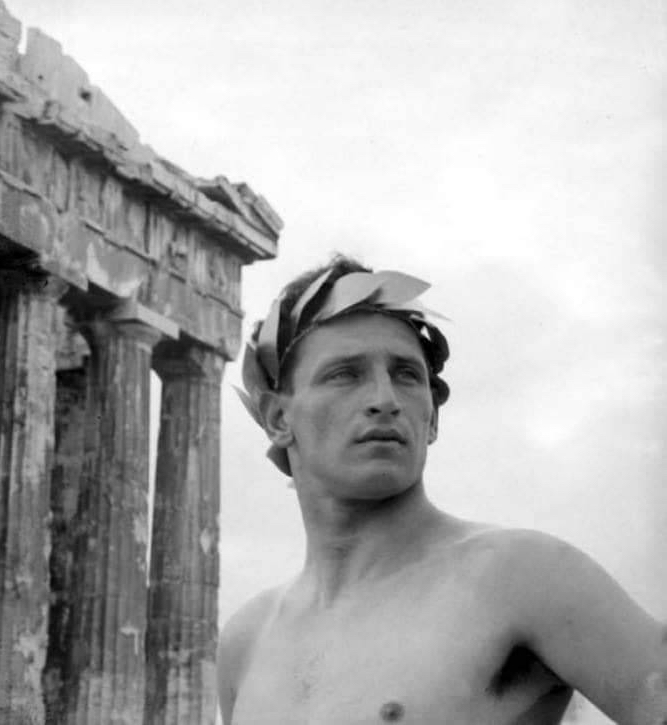

From the ancient city of Delphi to Athens’ Parthenon, Nelly captured her subjects within the boundaries of many significant ancient structures. By looking at the art of photography through a historical perspective and harmonizing this approach with a considerable amount of theatrical attitude, she produced aesthetically subtle shots which reimagined the ancient Greeks. There is no doubt that capturing these shots required creativity, but it required courage as well. When Nelly started taking photographs of nude female and male models within ancient sites such as the Acropolis, a firm conservative reaction rose from Athenian society and certain government officials. Acropolis’ cultural significance and what it spiritually symbolized made the structure “sacred” for the people of the city.

Part of the public considered posing naked near these national venues a “disrespectful act.” For Nelly, this reaction could have turned into backlash, which could have ultimately ended her career, at least in Greece. She was brave enough to demonstrate that human nakedness was not a discourtesy to these monuments, but in fact, a visual hymn to them. Nelly felt that their architectural forms were so pure that the subjects who were nude would be in harmony as this is the most unadulterated state of human beings. Of course, she had supporters as well, such as writer Pavlos Nirvanas. In 1929, he wrote,

I protest in the name of the Olympian deities, who, as is well known, not only walked in the open air unclothed, both male and female, but were worshipped stark naked in their temples.

Pavlos Nirvanas, Estia.

Additionally, archaeologist Alexander Philadelpheus, the director of Acropolis at the time, was one of her supporters as he personally joined some of these photoshoots.

As a female Greek photographer, the manner that Nelly embraced continues to be criticized but on a different scope this time around. Some scholars claimed that Nelly fed the stereotypes of the West regarding Greece and its ancient legacy. The argument targets the practice of adjusting Greek reality to the perception which was created by the West. Some of this criticism even went further to a point where they became accusations.

Nelly’s stance as an artist was compared to the director and Nazi propagandist, Leni Riefenstahl. Nelly’s style was interpreted as an attempt to prove “genetic purity of Greeks and racial continuity” which for some was a planned and intentional act that served the political narrative of right-wing entities. Was this really the case? When Nelly photographed the village maidens along with Archaic Age Kores, did she have any ideological purpose? Let history be the judge for that. I, however, humbly think that she merely pursued what she was fascinated with, that being the classical beauty of Greece and its consonance with the human body.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!