Masterpiece Story: Buddha Dated 338

Buddha dated 338 is a masterpiece of Buddhist art and Chinese art with deep historical significance. It exemplifies the early blending of Indian...

James W Singer 14 December 2025

Death has been a fascinating theme for artists since the beginning of time. It was imagined as a personified force, also known as the Grim Reaper, a living skeleton who causes the victim’s death by coming to collect them. In turn, people in some stories try to hold on to life by avoiding Death’s visit, or by fending it off with bribery or tricks. But this part of the visual imaginary won’t be a thing in today’s painting.

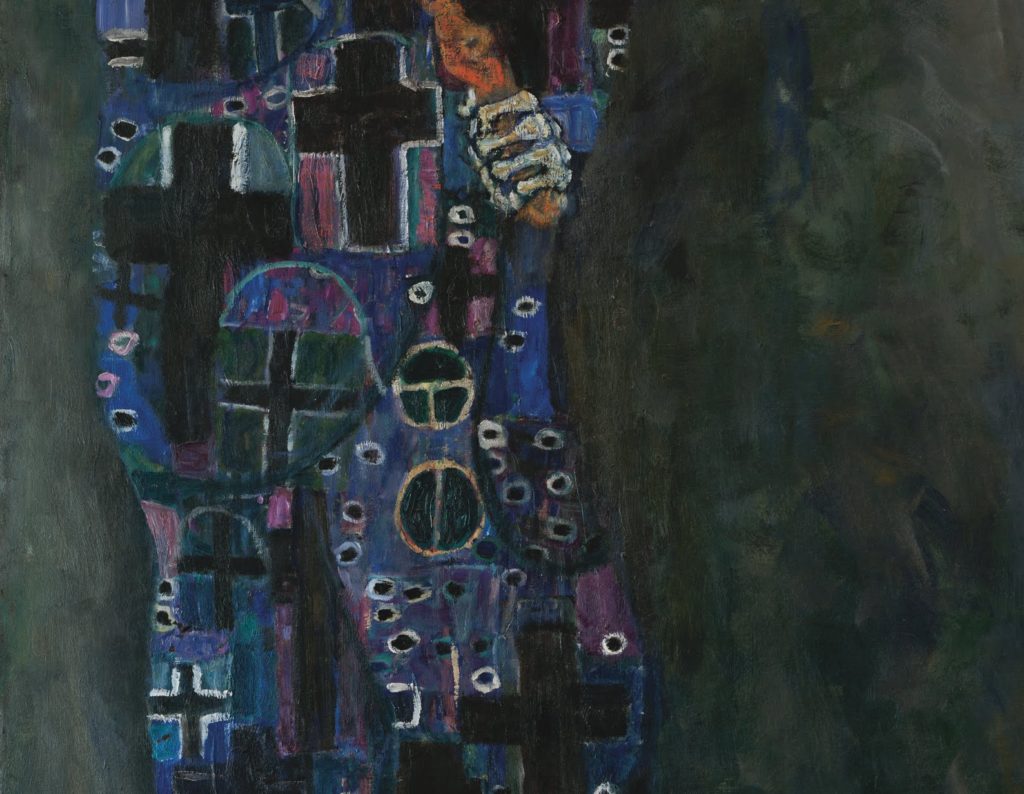

The painting we present today was made by Gustav Klimt in 1911, a couple of years before the world was set on fire by the Great War and before Klimt’s death due to the Spanish flu. Ironically enough, Death personification in art is mostly recalled in the context of the Middle Age’s plague epidemics.

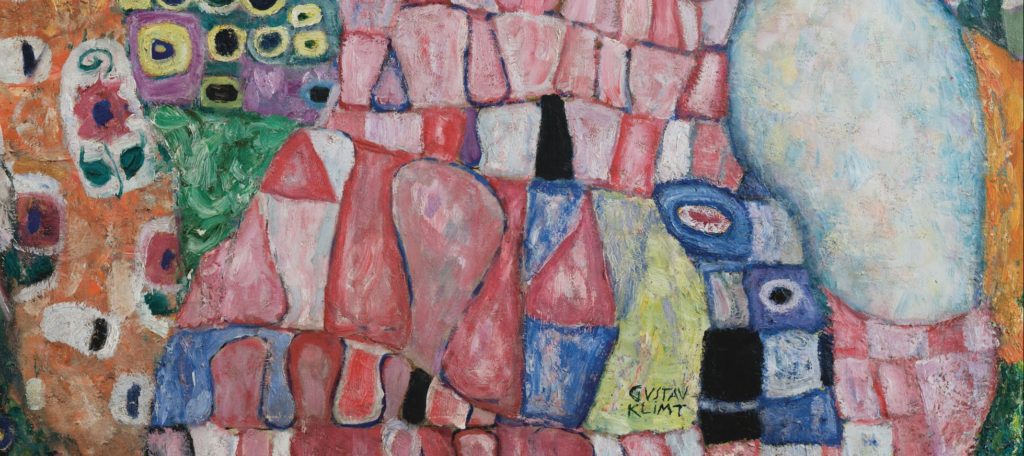

But this painting is different. Next to Death (who holds a club!), gazing at “life” with a malicious grin, we see the human surge that conveys a vibrant and hopeful impression. Naked bodies are huddled together and surrounded by a colorful abundance of flowers and ornamentation.

Every age group is represented, from the baby to the grandmother, in this depiction of the never-ending circle of life. Death may be able to swipe individuals from life, but life itself, humanity as a whole, will always elude his grasp. In a bold composition, the image represents a universal allegory through which the Viennese artist exemplified the cycle of human life. The circle of life repeats itself.

But coming back to the Great War. It has its mark here. For unknown reasons, Klimt decided to retouch the painting in 1915, in the second year of the war. It was also the year in which his beloved mother, with whom he lived until her last days, died. The figure of Death, in particular, was fundamentally altered. He also added figures to the mass of people and repainted the background.

Both the group of people and Death were treated in the very decorative way, typical for Klimt. We can see the echo of his famous “Golden Period” (The Kiss is of course the most famous masterpiece of that period). In 1903, Klimt traveled twice to Ravenna, where he saw the mosaics of San Vitale, whose Byzantine influence was apparent in the paintings. In Death and Life, the ornaments and their colors are having their meanings – black crosses on Death’s cape are opposed to the bright surrounding of the human figures, filled with flowers.

Gustav Klimt described this painting, which was honored with the first prize at the 1911 International Art Exhibition in Rome, as his most important figurative work.

Instead of a threatening vision of death, we see the acceptance of mortality. The moments of pleasure, beauty, youth, serenity, hope, and acceptance. The circle of life repeats itself on and on, at least in his vision.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!