10 Facts You Didn’t Know About Anthony van Dyck

Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish Baroque painter of remarkable skill, left an indelible mark on art history. His signature style of refined portraits and...

Jimena Aullet 24 October 2024

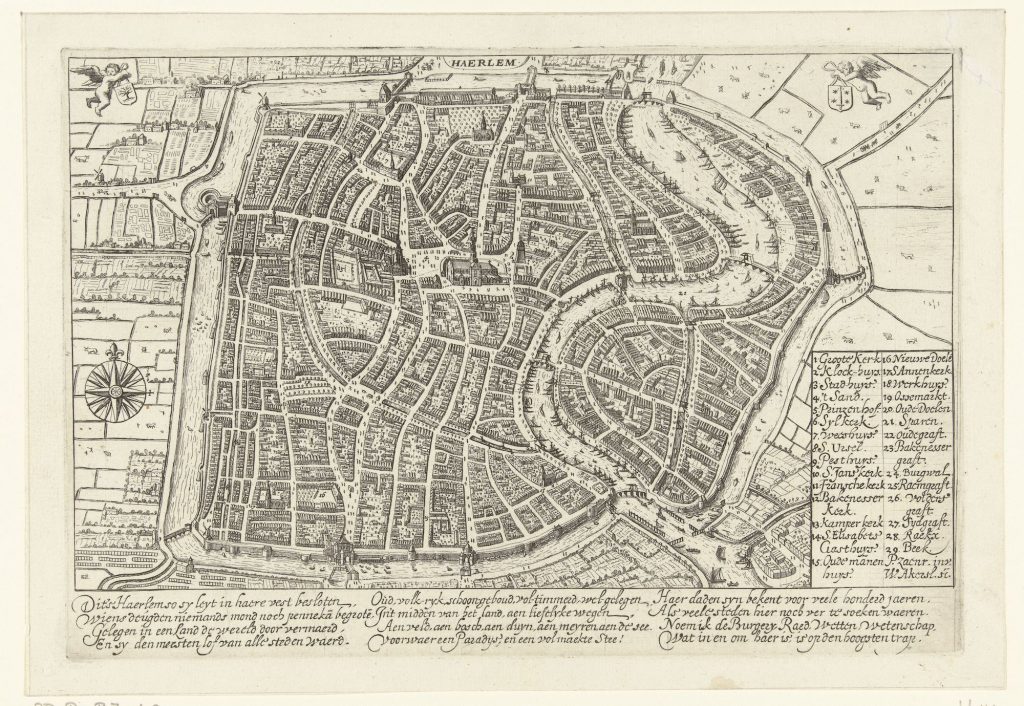

The city of Haarlem in the Netherlands was one of the flourishing art centers in the 16th and 17th century. Today, you can walk the streets of the city and see that not much has changed. Architecturally, the space is filled with reminders of a point in history when artists came up with new ideas and created new styles. Although Haarlem has a long history, dating back to before the Middle Ages, there was a specific time when the stars aligned and the city flourished – that period was known as the Dutch Golden Age.

Between 1575 and 1675, the following circumstances turned Dutch cities like Haarlem into artistic hubs. Firstly, artists, both male and to a lesser extent female, were able to prosper in Haarlem. Secondly, the church didn’t control artistic subject matters, unlike in the Southern Provinces controlled by Spanish Habsburgs or in Italy. Thirdly, there was an emergence of genre painting which put the Dutch masters at the forefront of innovation. And, fourthly, the city’s open market created conditions whereby artists could flourish and this led to the creation of some of the world’s greatest art.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Willem Outgertsz. Akersloot, after Pieter Jansz. Saenredam, Plattegrond van Haarlem, 1628, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

The number of major contributors to early Netherlandish art who were either born or active in Haarlem is surprising indeed.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde, View on the Bakenessergracht with the De Passer en de Valk Brewery, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands.

Female art masters were not as common as their male counterparts. Many steps were required to gain the official title of “master” artist; and it was more difficult, nay impossible, to obtain master status as a female due to society’s standards for women. However, the Haarlem school did produce female masters.

Judith Leyster was one of the first women to achieve master status in her profession, around the same time as Sara van Baalbergen. Across the whole region there were quite a few female artists who managed to obtain the title of Master, and were very active in the art world.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Judith Leyster, The Concert, ca. 1633, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, USA.

Often artists like Maria de Grebber were born into a family who owned and operated a workshop for artists. It may have been easier for de Grebbe, as members of her family already worked in the industry. In contrast, Leyster had to work her way into art because her family’s profession was in brewing.

Because the Northern Provinces did not adhere to the religious practices of their Southern neighbors, there was an opportunity to produce a vast array of art that counter balanced that of the Catholic Church. The presence of religious diversity combined with the booming economy, created a new demand for art. This meant that the majority of artistic production dealt with genre scenes – including domestic interiors, scenes of everyday life with an emblematic or moralistic meaning to them. Below is a graph from the National Gallery of Art’s Painting in the Dutch Golden Age. We can read from it that the number of works depicting biblical themes decreased in the second half of the century from over 42% to 18%.

Graph from Painting in the Dutch Golden Age: A Profile of the 17th Century, 2007, p. 40, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

One particular genre specific to Haarlem was Haerlempjes. The name denotes the very specific genre of painting the landscapes of Haarlem.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Reyer Claesz Suycker, View of Haarlem, ca. 1630s, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands.

One of the oldest art museum in Holland is located in Haarlem. It is named after the Dutch artist, Frans Hals, who spent most of his life and career in the city of Haarlem. The Flemish-born Hals is one of the most celebrated portraitists of the Dutch Golden Age, second only to Rembrandt and Vermeer.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Frans Hals, Banquet of the Officers of the St Adrian Civic Guard (the Calivermen), 1627, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands.

The museum has created an immersive learning experience on the artist behind the paintings, known as The Hals Phenomenon, giving visitors an opportunity to learn about him before exploring his actual work in the gallery.

Installation view: The Hals Phenomenon, The Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands.

Guilds helped to build the socioeconomic world of Europe in the 11th to 16th centuries. Though their purpose changed over time, guilds served as an “association of craftsmen or merchants formed for mutual aid and protection and for the furtherance of their professional interests.”

Concerning Haarlem, the Guild of St. Luke consisted of artists of various practices; the most common guild for artists named after St. Luke, the patron saint of artists, surgeons, and doctors. However, in a later reformation of the Haarlem guild’s charter, painters stepped up to ensure that they would be given a higher place among their creative peers:

[O]ur first and greatest concern is the renewal of the ancient luster of the art of painting, which was always held in the highest esteem by the olden kings and princes…[I]n the first place, this guild of St. Luke consists of painters, the largest and most important of its constituent groups.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Jan de Bray, The Governors of the Guild of St. Luke, 1675, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Taverne stated that “article after article reflects a bias in favor of the painter and his art.” Even if they sat higher on the intended pyramid of artists in the guild, the painters still experienced restrictions on what they could and couldn’t do.

Haarlem in the Dutch Golden Age: Jan de Bray, Portrait of the Artist’s Parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna Westerbaen, 1664, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

A name that continuously popped up in researching the Guild of St. Luke in Haarlem, as well as the reformation of the group in the 16th century, was De Bray; both Salomon and his son, Jan. The surviving archives point to the fact that the Haarlem guild archives consisted of documents made by Salomon de Bray, or under his supervision. To that point, according to E. Taverne:

Bray turned the traditional guild into a smoothly functioning trade union. [T]hroughgoing study of the surviving archives has brought to light the reforms in the charter of 1631. We now see them to be the direct expression of a distinctly new conception of the place of the painter and his work within the guild.

Salomon de Bray and the Organization of the Haarlem Gild of St. Luke in 1631, p. 50.

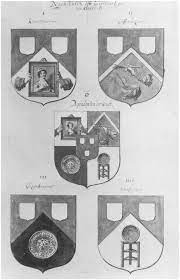

Salomon de Bray, Coats-of-arms for the guild od St. Luke: “De Konst,” 1635. from E. Taverne, Salomon de Bray and the Organization of the Haarlem Gild of St. Luke in 1631, p. 68.

Liedtke, Walter. “Frans Hals (1582/83–1666).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York“ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Snyder, James E. “The Early Haarlem School of Painting: I. Ouwater and the Master of the Tiburtine Sibyl.” The Art Bulletin 42, no. 1 (1960): 39-55.

Taverne, E. “Salomon de Bray and the Reorganization of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke in 1631.” Simiolus Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 6, no. 1 (1972). pp. 50-69.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!