According to recent news, the President of Turkey has converted Istanbul’s famous Hagia Sophia back into a mosque. His decision is highly controversial, given Hagia Sophia’s reputation as a major monument of human history. Here is the historical, religious, and political background for this charged issue.

It Was Originally a Byzantine Church

Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) was constructed from 532-537 CE as an Orthodox Christian church, the third one to inhabit this site. At the time, Istanbul (then called Constantinople) was the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565) ordered the construction, and geometry specialists Isidorus of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles were the architects. As the seat of the Orthodox Patriarch, Hagia Sophia was the world’s most important Orthodox cathedral for nearly a millennium. It was also the official church of the Byzantine Emperor and an important pilgrimage destination.

After the Ottoman Conquest, It Became a Muslim Mosque

Things changed dramatically for Constantinople in 1453. In that year, Ottoman Turks conquered this last Byzantine holdout. They renamed the city Istanbul and absorbed it into the Ottoman Empire. As Muslims, the Ottomans converted Hagia Sophia into a mosque, renovating it as necessary to serve their needs. The Hagia Sophia we know today reflects its dual its Byzantine-Ottoman and Christian-Muslim history.

It Has Been a Museum Since 1934

The Turkish Republic secularized Hagia Sophia shortly after succeeding the Ottoman Empire in 1922. Turkey’s first president, Kemal Ataturk, wanted Hagia Sophia to be “a monument for all civilization,” so the Turkish government officially made it a museum in 1934. In that capacity, it was open to visitors of all faiths. For over eight decades, no religious services took place at Hagia Sophia; in fact, public prayer was long illegal there. Instead, the building became a major tourist attraction.

It’s Central to Two Religions and Cultures

With its dual Byzantine-Ottoman heritage, Hagia Sophia holds centuries-long significance to two major cultural and religious groups. As such, some Turkish Muslims and Greek Orthodox Christians have previously called to reclaim the monument for their respective faiths. Staying neutral suited Turkey’s secular, pro-western aims in the 20th century, but the country has become more openly Muslim since President Erdogan was elected in 2003. This is not the first church/mosque to become a mosque again during the Erdogan administration.

As a museum, Hagia Sophia was as close to politically neutral as it could probably get, since it did not favor one group at the expense of the other. As a mosque, that’s no longer the case. The recent decision has alienated the Greeks, since the Greek Orthodox Church is the modern descendant of Byzantine Christianity. Greek culture minister Lina Mendoni called the decision a “direct challenge to the entire civilized world”. The Russian Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Pope have also spoken out against conversion. While some Turks dislike the President’s decision, others have responded joyfully to the possibility of worshiping inside Hagia Sophia once more.

It’s Not the Only House of Worship to Serve Multiple Faiths

Hagia Sophia is special in many ways, but the fact that it has served multiple faiths is definitely not one of them. This is actually much more common than one might think. For example, the Pantheon was originally a Roman temple but later became a Christian church, while the Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba in Spain includes both a Catholic church and a Muslim mosque within its walls. Some Southeast Asian temples, meanwhile, have served both Hinduism and Buddhism. There are both practical and political reasons for this phenomenon, which often ensures a building’s continued survival. We probably have conversion to thank for saving Hagia Sophia, whereas little else of Byzantine Constantinople survives in modern-day Istanbul.

Hagia Sophia Is a Masterpiece of Art and Architecture

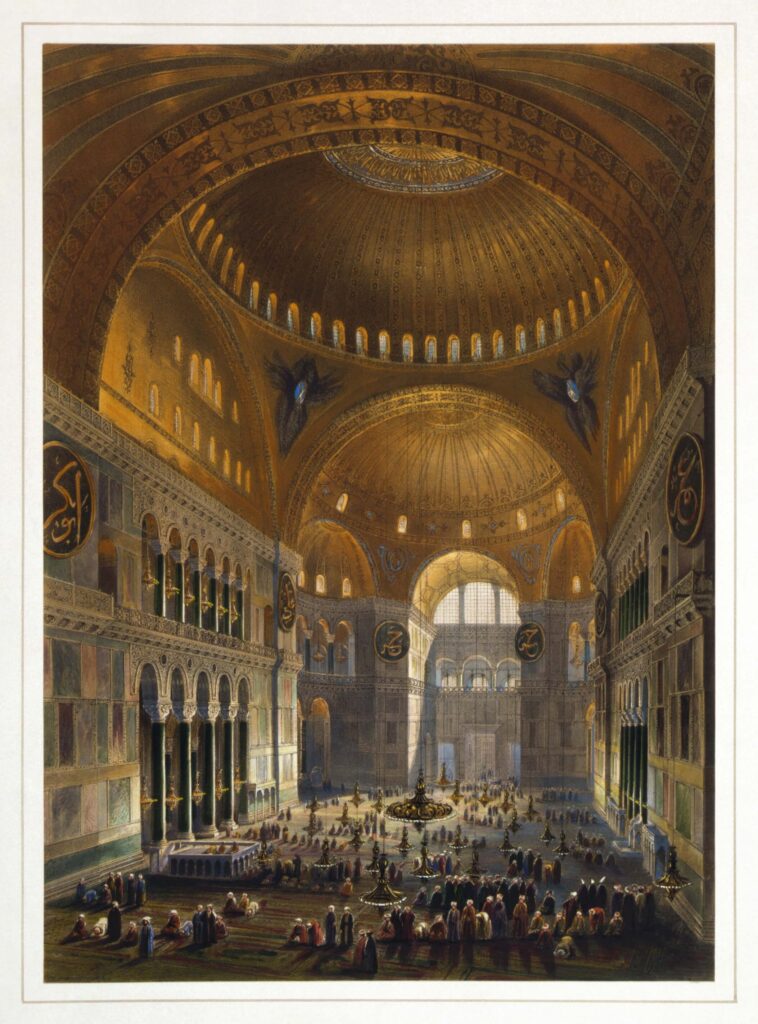

The Dome

Hagia Sophia’s crowning glory is its gorgeous dome, which is 110 feet in diameter and flanked by two half domes. The building was revolutionary for setting a round dome elegantly on a square structure, using curved triangular forms called pendentives to bridge these dissimilar shapes. Clerestory windows ringing the dome give the illusion that it floats unsupported. A 6th-century writer observed that it looked “as though it were suspended from heaven by the fabled golden chain”. What we see today isn’t the original version; that one collapsed in 558 CE and had to be reworked. Despite their Christian origins, Hagia Sophia’s domes and half domes inspired other important mosques built in Istanbul.

The Mosaics

Inside, Hagia Sophia is luminous, spiritual, and mysterious. The building abounds in decoration, including colored marble embedded in the walls (called “revetment”). The imported marble was cut in a special way in order to emphasize the natural veining patterns. Originally, the building had only abstract and foliate (plant-inspired) decorations, including brilliant mosaics of gold, stone, and colored glass that give an otherworldly air of golden-yellow divine light.

Hagia Sophia’s most celebrated mosaics, masterworks of Byzantine artistic achievement, are the elegant and spiritual figurative images. They aren’t original but rather came about in the nine centuries after construction. The most famous include the 13th-century Deësis mosaic, which depicts Christ, the Virgin, and John the Baptist, and the 9th-century Theotokos, showing the Virgin and Child seeming to float in the half dome above the apse. Other mosaics depict Byzantine rulers alongside holy figures.

Islamic Additions

During the Ottoman period, Hagia Sophia acquired Islamic furnishings, including a mihrab (niche facing Mecca), four now-iconic minarets, and decorations featuring Arabic calligraphy. The written word is a key motif in Islamic art. Script adorns the very top of the central dome, though the series of massive calligraphy roundels are more immediately apparent.

Hagia Sophia’s present appearance is a unique product of its dual identity, with original Byzantine elements existing side-by-side with later Ottoman renovations. However, the building would never have displayed its expressly Christian and Muslim elements concurrently during its functional life as it did during its museum era. Part of what’s so fascinating about Hagia Sophia is how it shows its entire history simultaneously… but maybe not for much longer.

The Mosaics Are Key To the Controversy

In the art world, much of the backlash surrounding Hagia Sophia becoming a mosque concerns the mosaics. The Islamic faith prohibits humans and animals from being represented in art, so an active mosque cannot have visible mosaics portraying Christian religious figures. During Hagia Sophia’s last interval as a mosque, some Christian mosaics were destroyed, while others were covered with whitewash. Those surviving examples reappeared when the building opened as a museum.

Turkish officials claim that they will not damage the images, saying they will preserve them as prior generations did. SmithsonianMag.com reports that authorities propose to use lights and curtains to hide the mosaics during services, then unveil them for tourist visiting hours. But is this feasible for mosaics like the huge Theotokos located high up in a half dome? Even if the building itself remains accessible to the public, not being able to see the mosaics would be a huge loss.

Interestingly, the very same commandment against creating “graven images” that underpins Islamic attitudes about representation also led the Byzantines to several periods of iconoclasm – the destruction of images. The theological issues behind iconoclasm boil down to the question of whether icons of religious figures merely aid in worship or actually become the object of worship in themselves. In fact, iconoclasm is the reason why Hagia Sophia did not originally include figurative mosaics.

Turkey Plans to Still Admit Tourists

The Turkish government currently promises to continue welcoming tourists inside Hagia Sophia outside of scheduled service hours.

“Hagia Sophia, the common heritage of humanity, will go forward to embrace everyone with its new status in a much more sincere and much more unique way.”

– Turkish President Recep Edrogan, as quoted in The New York Times.

As Turkish officials have pointed out, other famous houses of worship hold services while also admitting members of the public. Using great Parisian churches Notre-Dame and Sacre Coeur as evidence that the two purposes can co-exist, they argue that there’s no reason Hagia Sophia can’t function similarly. This line of reasoning has merit, but only if Hagia Sophia follows a similar policy of welcoming everybody, regardless of religion. Will this actually be the case? And how much of the building will visitors still be allowed to see?

The UN Has Something to Say About All This

“UNESCO deeply regrets the decision of the Turkish authorities, made without prior discussion, and calls for the universal value of World Heritage to be preserved.”

Hagia Sophia is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, one of 18 in Turkey. It’s part of Historic Areas of Istanbul, which also includes the Hippodrome of Constantine, Topkapi Palace, and the Blue Mosque. UNESCO has called for dialogue and stated in a press release that “States have an obligation to ensure that modifications do not affect the Outstanding Universal Value of inscribed sites on their territories.” Unfortunately, it appears that UNESCO doesn’t have much in the way of recourse against nations who decide not to respect these obligations.

In Summary

The act of revoking Hagia Sophia’s museum status and turning it back into a mosque is highly controversial, and strong feelings on the issue aren’t likely to fade quickly. As I hope you’ve realized by now, Hagia Sophia’s history is complex and fascinating. The church/mosque’s multifaceted past makes today’s issue even thornier. However, it seems that there’s nothing anybody can do except wait to see what happens in the long run. Services will begin at Hagia Sophia on July 24, 2020.

Works referenced:

- Allen, William Allen, “Hagia Sophia, Istanbul,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. “A Monumental Struggle to Preserve Hagia Sophia“. Smithsonian Magazine. December 2008. Accessed online.

- Davies, Penelope J. E. et al. Janson’s History of Art, The Western Tradition. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2007. P. 256-260.

- Gall, Carlotta. “Erdogan Signs Decree Allowing Hagia Sophia to Be Used as a Mosque Again“. The New York Times. July 10, 2020, updated July 15, 2020.

- Macaulay-Lewis, Elizabeth and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Hagia Sophia as a mosque,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2015.

- Machemer, Theresa. “Turkey Controversially Converts Hagia Sophia From Museum Into Mosque“. Smithsonianmag.com. July 13, 2020.

- Stoilas, Helen. “Hagia Sophia will be mosque again, Turkish president Erdogan says“. The Art Newspaper. July 10, 2020. Accessed online.

- Wegner, Emma. “Hagia Sophia, 532–37.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2004).

Read more about mosques and Islamic art: