Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

27 January 2025 min Read

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger is one of those paintings that we know so well we tend to forget to look closer. It’s like the Mona Lisa or The Sunflowers, a part of our universe of images. But there is so much to look at here, so many clues and mysteries to interpret. It is also a beautiful painting, with rich colors and varied textures, it looks like a lush gem encased in the frame. It even tells a story through the crafty use of symbols. Let’s take some time to really look and hear what the painting has to tell us.

Holbein completed The Ambassadors in 1533. This was the same year when Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn. He did this despite his previous wife, Catherine of Aragon, still being alive, making it an open defiance to the papacy. The country and, in fact, all of Europe were in a religious crisis, as only 16 years earlier Martin Luther had published his Ninety-Five Theses, which are perceived as the beginning of Reformation.

Now with Henry VIII threatening to leave the Catholic Church, the situation was even more unstable. It was a decision of a magnitude comparable to the recent Brexit situation; you may even say there is a pattern here. It was in those uncertain and stormy times that Holbein came to England for the second time.

Hans Holbein was a son of Hans Holbein, hence he is the Younger. Born in Augsburg, Germany, by 1515 he moved to Basel. In 1523, he painted his first portraits of Erasmus, the man who opened the path for him to travel to England, by recommendation to Thomas Moore. It was for Moore’s circle that Holbein worked during his first stay in England in 1526-1528. He then returned to Switzerland to preserve his citizenship.

In 1532, Holbein returned to England. He was very attuned to changing political and religious mood, and therefore he distanced himself from his previous patron, Thomas Moore. Rightly so, as it proved, as Moore resigned from his position in 1532 and fell out of favor, only to be executed in 1535. So even in those turbulent times, Holbein was able to secure orders and quickly became the court painter of Henry VIII. This painting, however, was completed shortly before his official status changed.

Who are our ambassadors? Actually, until 1900 it was a mystery. Then Mary F. S. Hervey published Holbein’s Ambassadors: The Picture and the Men and identified our mysterious sitters. On the left, we see the man who ordered the painting: Jean de Dinteville. He was the ambassador of Francis I, the King of France. He was on his second mission to England back then, conveying messages between the kings. As far as is known from Dinteville’s letters, he did not enjoy his stays in England too much.

He cherished the visit from his friend Georges de Selve, the bishop of Lavaur, in 1533. Selve was in England on a diplomatic mission, however we don’t know the details. He used this chance to spend time with his close friend, Dinteville. We don’t know how Dinteville came up with the idea of commemorating this visit with a double portrait, but I am happy that he did. Otherwise, we would not have this amazing painting. We know both men were in their 20s, Dinteville’s age is marked on the scabbard of his dagger, while Selve’s is marked on the edge of the book he is leaning on.

The painting conveys its symbolic message on many levels, starting with the composition. You can see it is clearly divided into three horizontal zones. We have here the clearly delineated top part, with the men’s faces and torsos, delineated by the line of their elbows leaning on a table. Then the middle area with the objects placed at the bottom shelf of the table. And the bottom part with the floor mirroring the Cosmati Pavement of Westminster Abbey and the most mysterious object of all (I promise we’ll come back to it).

There are many interpretations possible of this division, one of the most common is that the top part symbolizes the heavens, the middle the earthly life, and the bottom death and what comes after.

But if we also pivot our gaze and look left to right we’ll find a clear delineation here as well, though in this case it is driven more by the sitters and their attributes. Dinteville is richly dressed, the fur of his coat so soft that we want to touch it. We can almost hear the rustling sound of the satin of his tunic. His clothing decorated with golden thread, a rich golden chain, and a skull-shaped pin in the hat. This is a man of action, as clearly indicated by his hand on the dagger. He is decisive and he gets things done.

On the other hand, Selve’s cloak seems deceptively simple. However, it is not, as the material is richly decorated and was extremely expensive at the time. Yet he comes across as more passive and contemplative in nature, a manner underlined by the book he is leaning on.

Let’s look closer now at the top part of the painting. On the table, we see a host of instruments associated with the heavens. We have here a celestial globe, portable sundial, and other instruments used to measure time, altitude, and the position of the stars and other celestial bodies. As far as we know, Holbein probably didn’t own them. But he did know the royal astronomer, Nicholas Kratzer, who certainly owned such objects. Holbein even painted Kratzer’s portrait, it is now in the Louvre.

Some researchers also point out that the readings of all the instruments are out of synch, indicating the chaos in the world. Another opinion is that this part also focuses on science, which, while giving us more and more, cannot provide answers for them all.

The rug on which the objects are placed is one of many examples of oriental rugs presented in Renaissance painting. They serve as useful documentation to this day on the patterns of such rugs. Unsurprisingly, not many of the actual objects survived as long as their depictions.

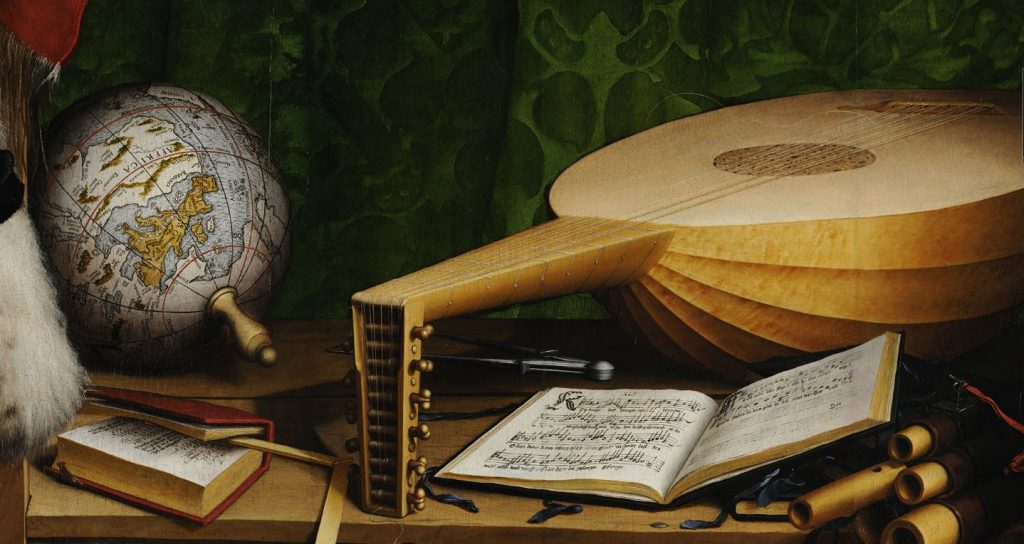

The sphere under the table focuses on earthly pursuits. We have here a terrestrial globe, with a map that is slightly different from what we know about the world now. It also shows Dinteville’s seat in France. There is a book on mathematics, opened on the page about division. There is a lute, beautifully foreshortened, but with a broken string. And there is a book of Lutheran hymns. The hymns are Come Holy Ghost and The Ten Commandments.

Selve may have wanted to include them because they express Christian unity, unlike the lute and book on division. This whole section is about the political and religious division that was overtaking the world back then.

Still, it is very difficult to focus on all the items above until we figure out what is the weird thing in the middle of the floor. Many of you probably know by now it is a skull. It is rendered in anamorphic perspective and can only be clearly seen when looking from the bottom right corner of the painting. Why is it like this?

We don’t have a clear answer, but there are several theories. For one, it certainly shows Holbein’s skill, but so does the remainder of the painting. Did he really have to show off?

Another theory suggests that the painting was meant to hang on a staircase and would be approached, allowing the viewers to gradually uncover the surprise. It most probably also serves the purpose most skulls in paintings do: as a memento mori. The distortion may be a dark joke on us. No matter how hard we try to avoid looking at it, death will come for us all.

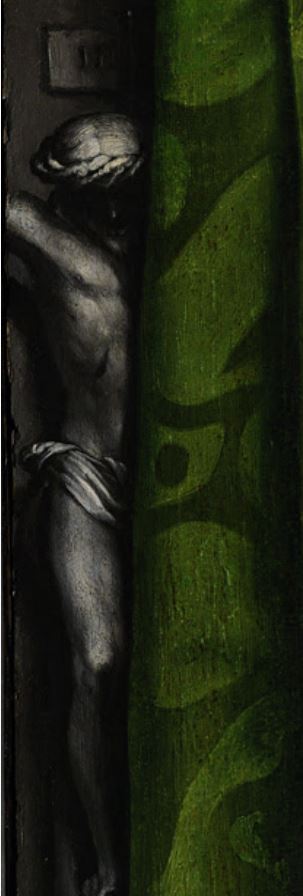

There is another object, that though not in plain sight is cleverly hidden and may provide some consolation. It is the crucifix in the top left corner. Barely visible from behind the green curtain, yet the symbol of salvation is still there. Despite all the discord in the world, despite all of us inevitably having to die, there is hope in eternal life.

It is an amazing combination of exquisite painterly technique with elaborate symbolism. A painting you can interact with in many different ways. From admiring the various colors and textures to an in-depth academic reading of the symbology. On some days you may come to it for its pure beauty, on others you may treat it as one of many painterly riddles to be solved. It is also a wonderful example of the representation of power. Just compare it with the two pictures below from the G7 summit in 2018 and the Brexit deal announcements. How our mighty have fallen, when compared to the confidence and power exuded by The Ambassadors.

If you cannot travel to London, there is an amazing opportunity to explore this painting online at Google Arts & Culture. You will never be able to get so close to it in real life as you can using their website. It is really worth the time, you can zoom in to see the cracks in paint, to read the words of the hymns, the maps, and readings on the scientific instruments.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!