Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

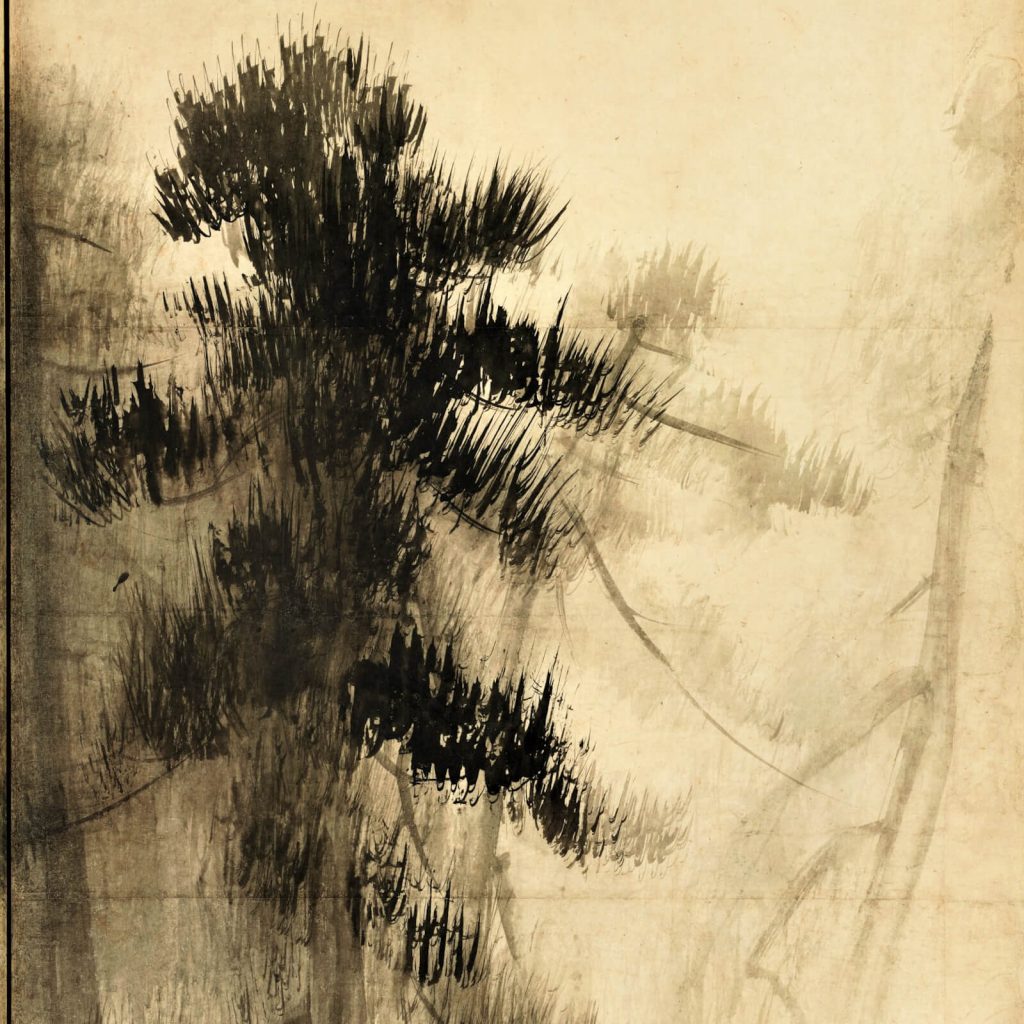

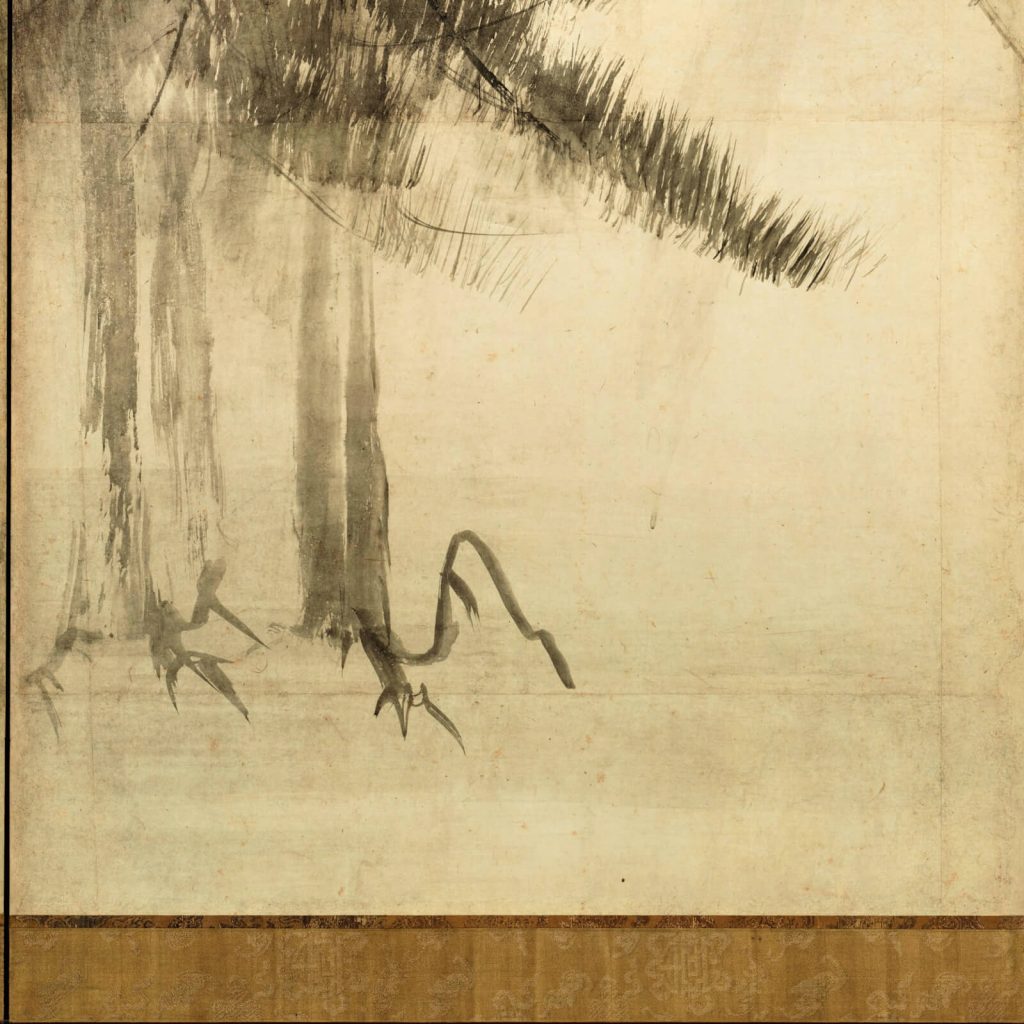

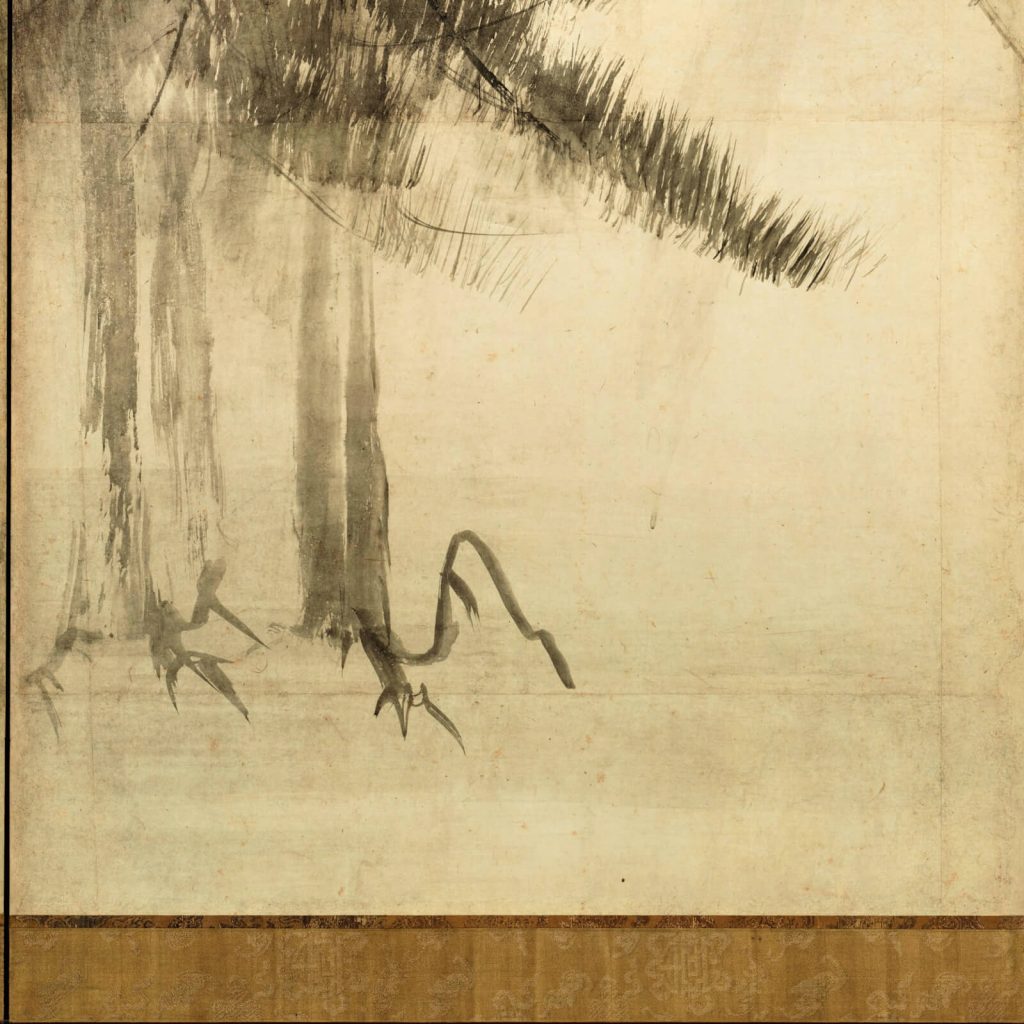

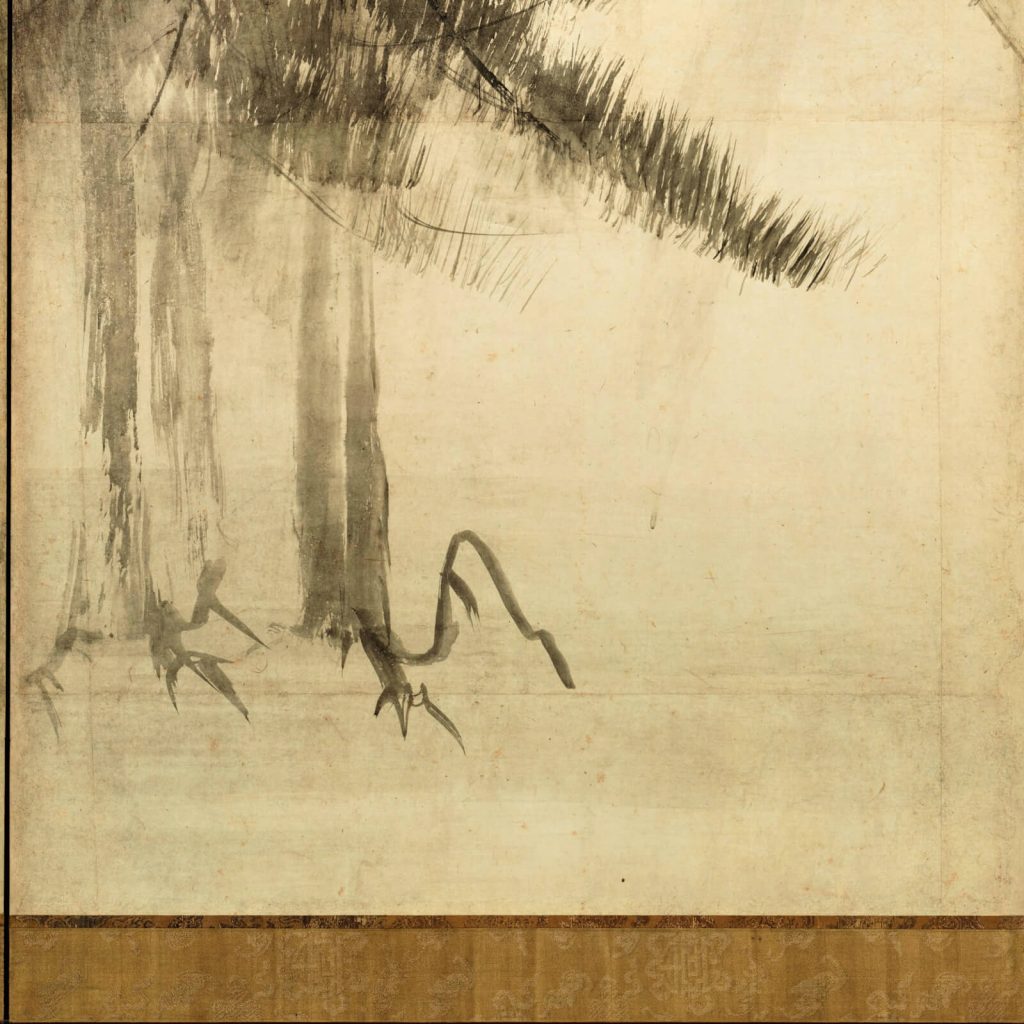

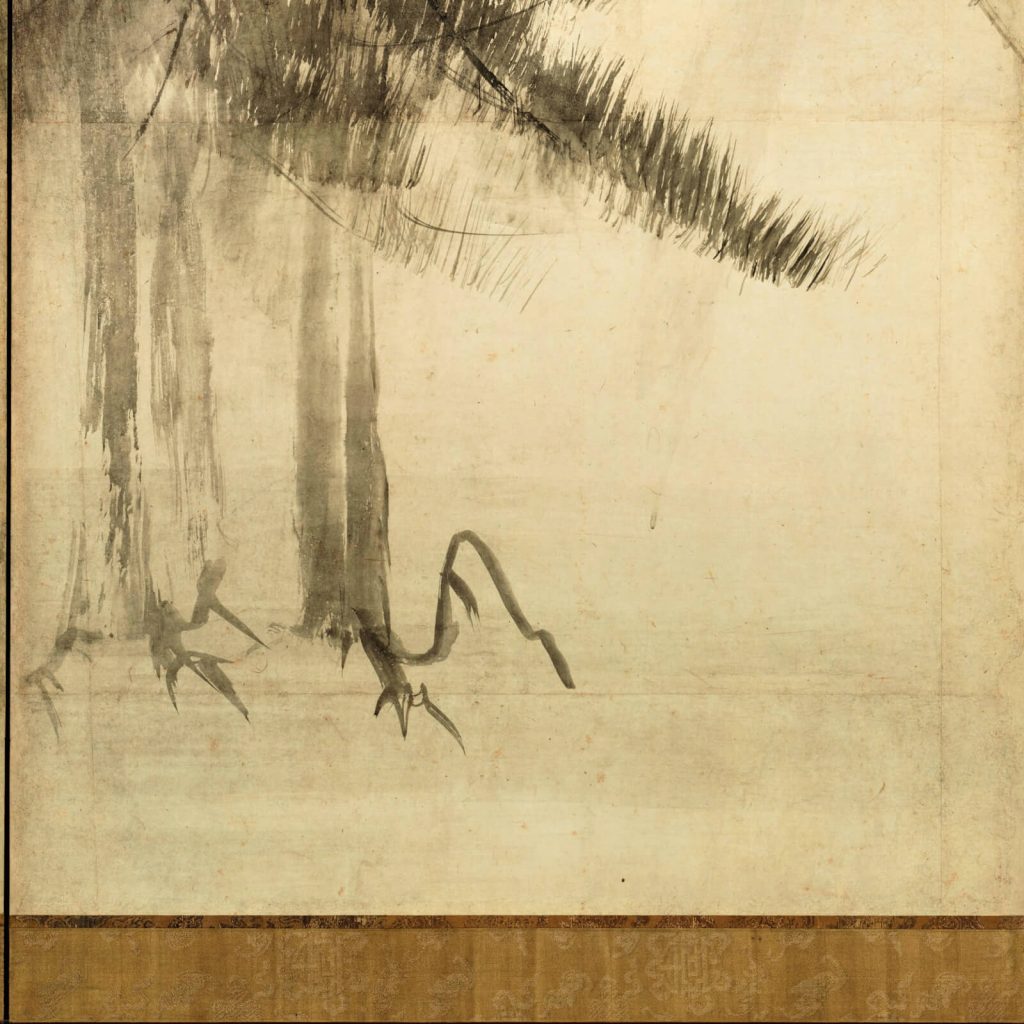

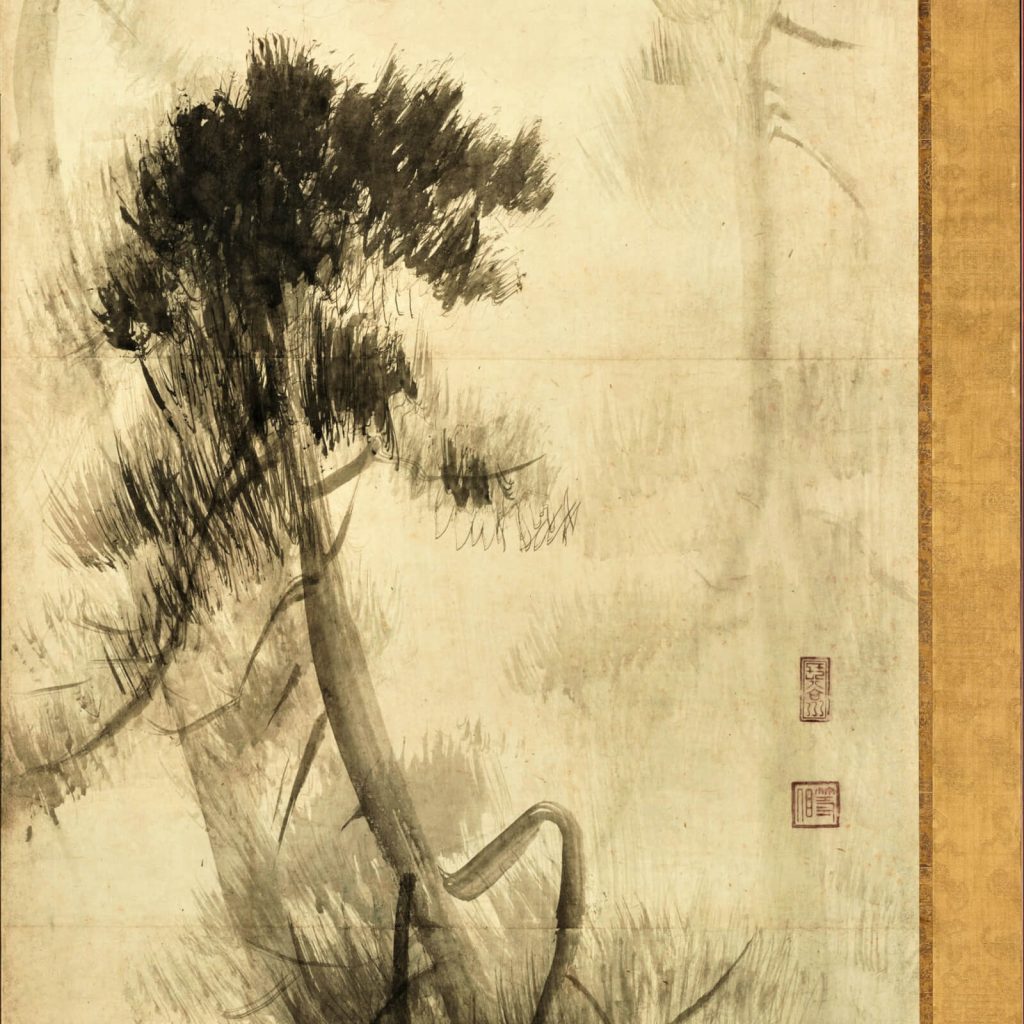

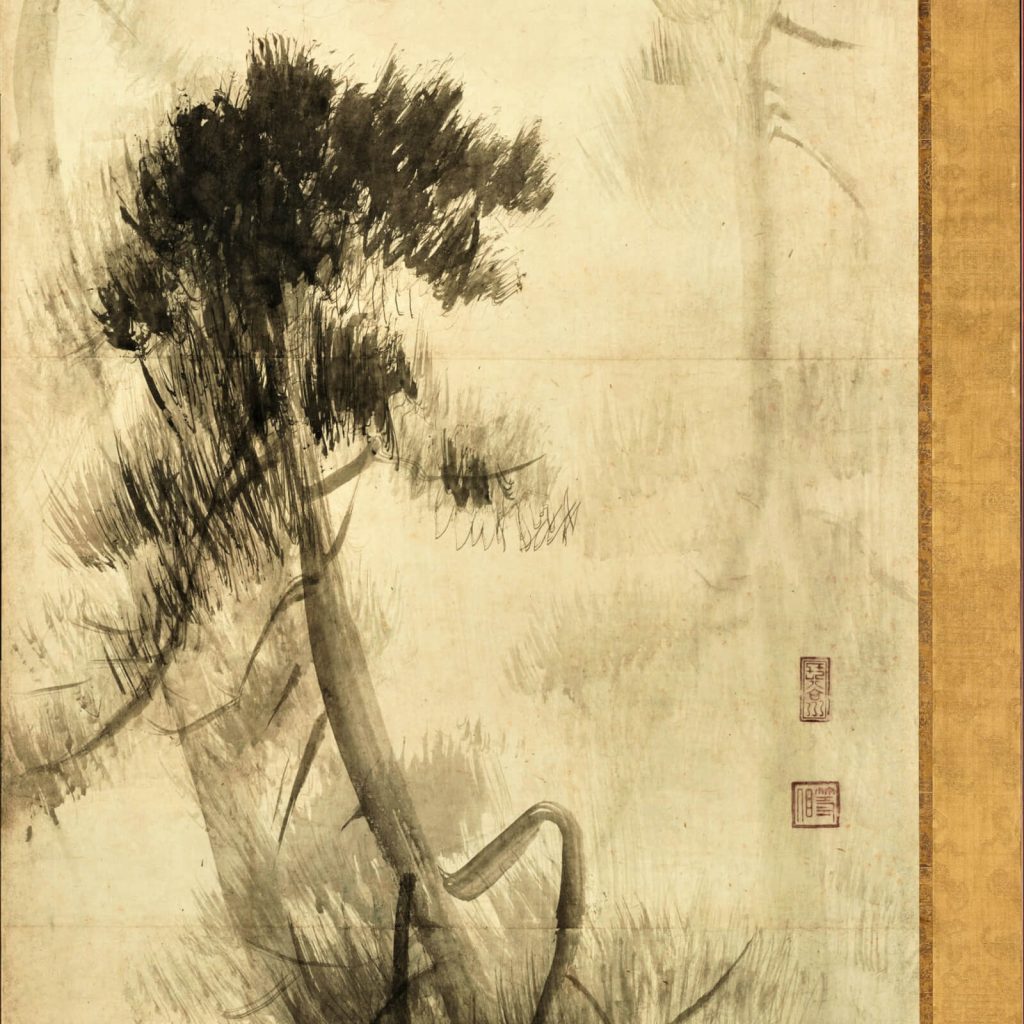

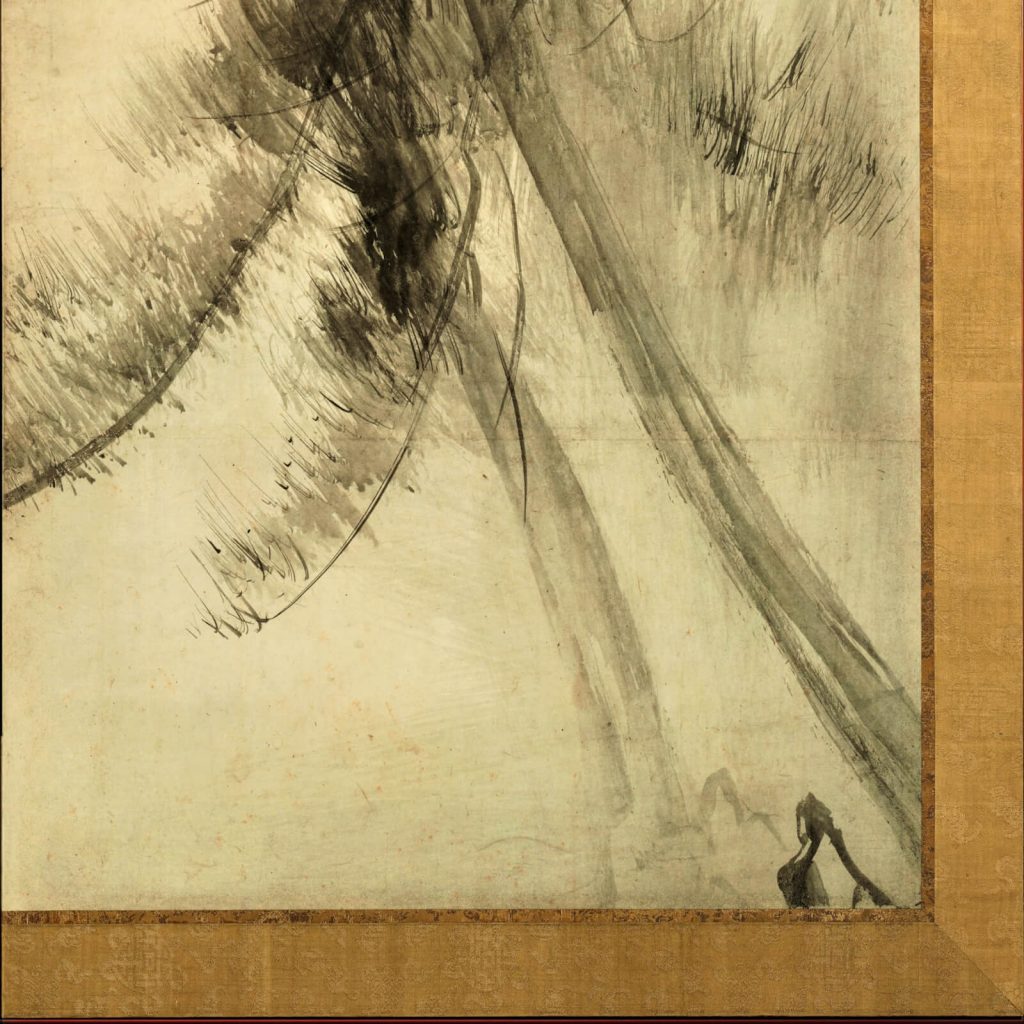

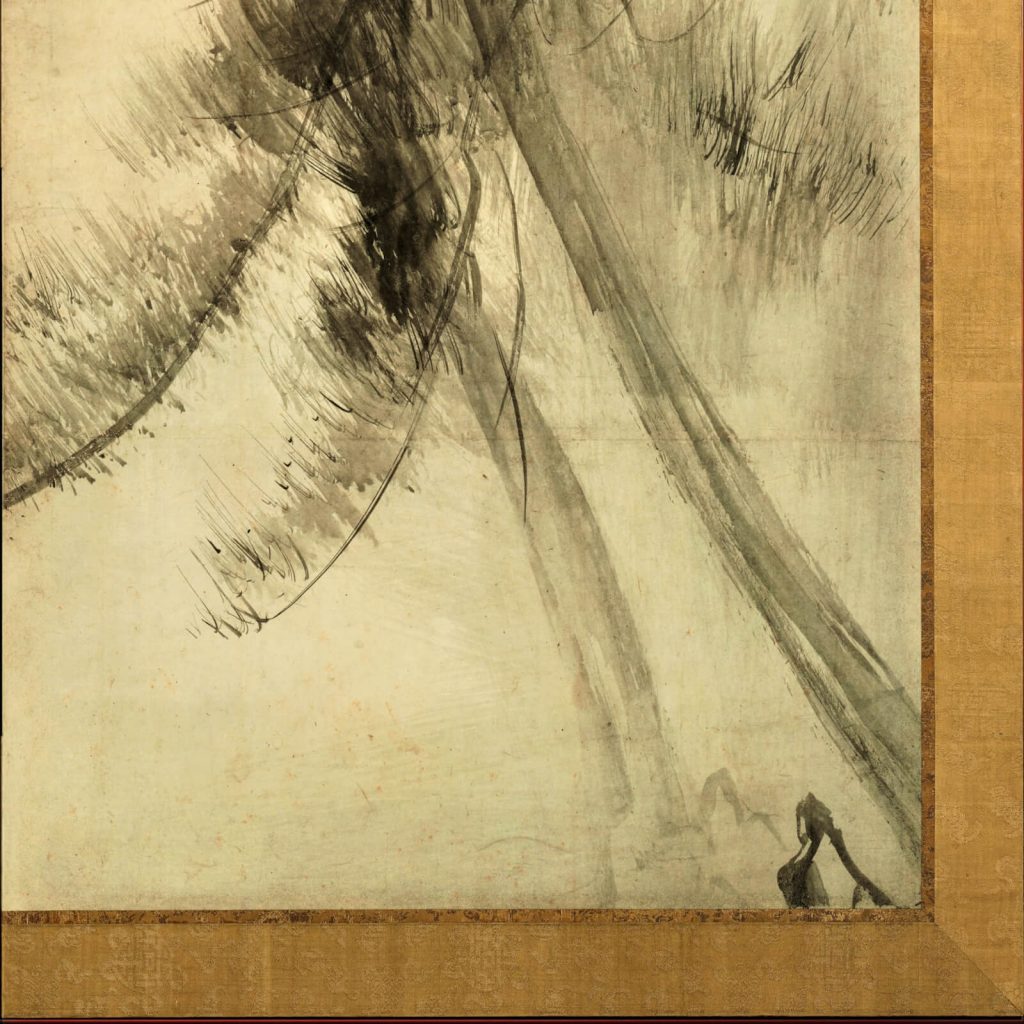

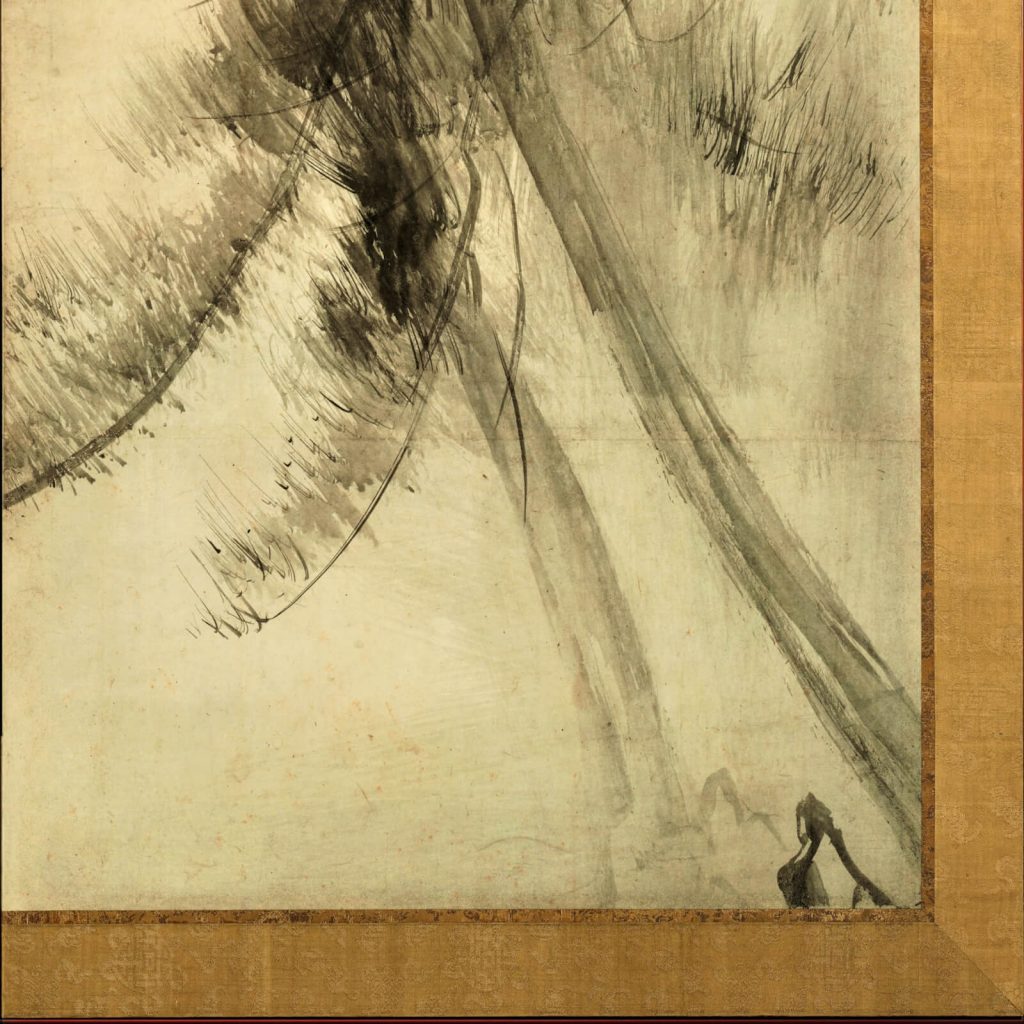

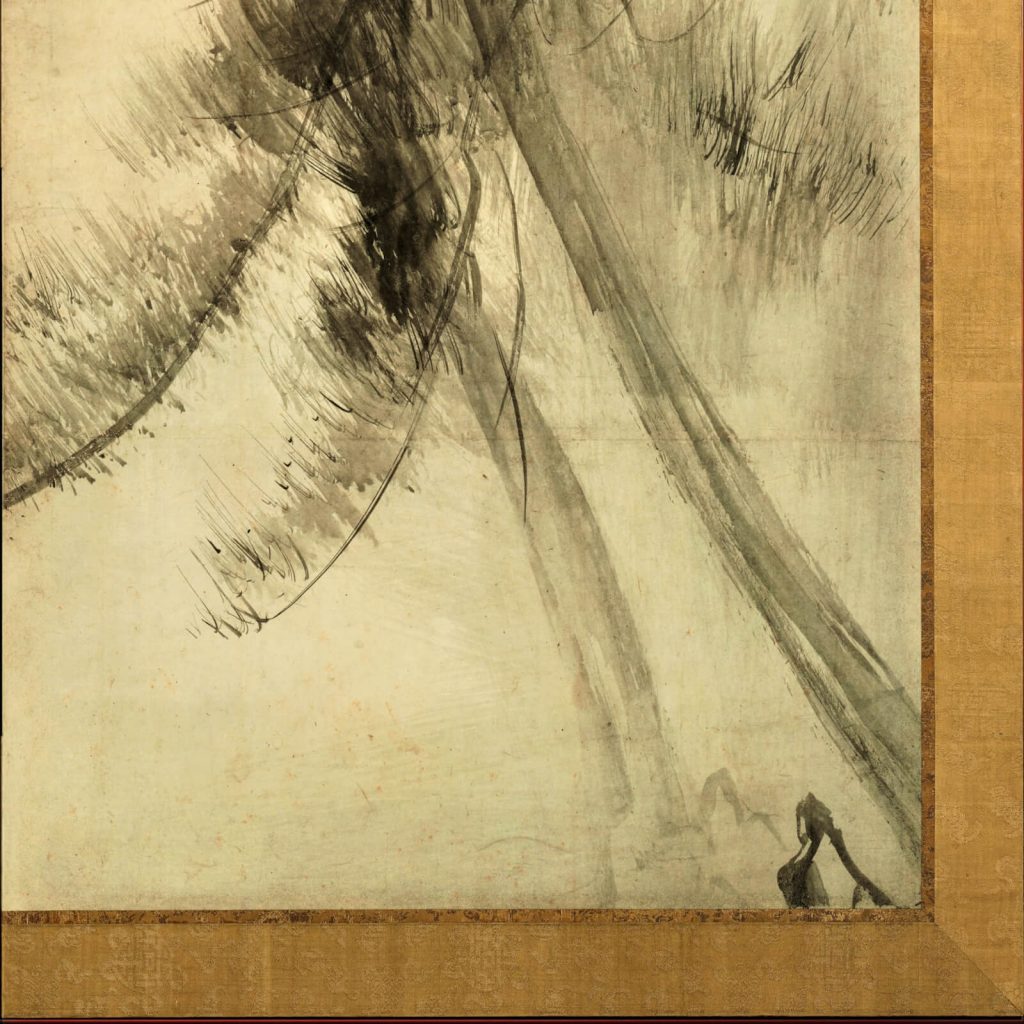

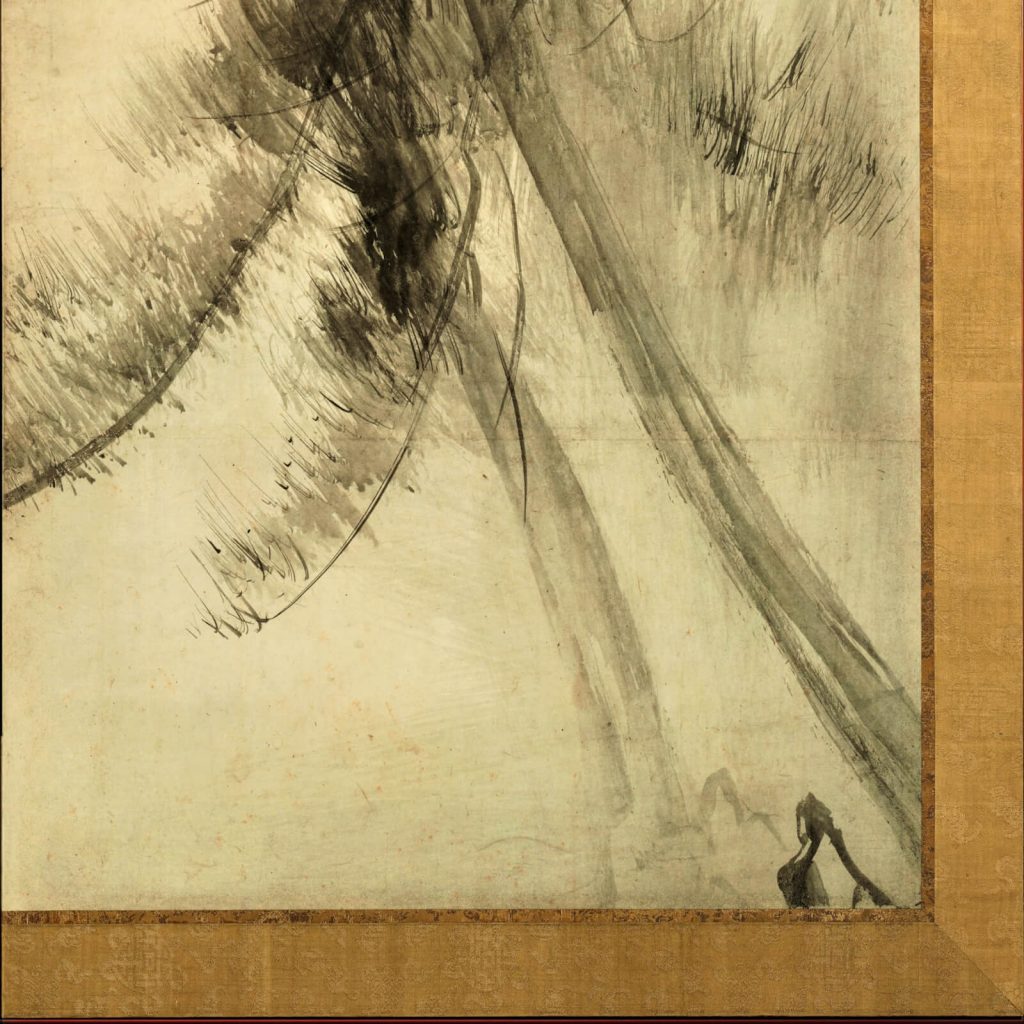

Japan is a country of distinctive traditional arts such as tea ceremonies, calligraphy, and bonsai. A rich history of artists fills their museums with breathless wonders. Pine Trees by Hasegawa Tōhaku is one such national treasure. It is a wonderfully complex painting despite its simplistic first impressions. Hasegawa Tōhaku may have only used simple tools such as bamboo sticks with split ends and bundles of rice straw to create Pine Trees but his effects are intricate and sophisticated.

Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610) lived and worked during the Momoyama period (1573–1615) in Japan. Momoyama means “peach blossom hill” and it was the beginning of Japan’s unification under a central government. It was also Japan’s transition period from medieval to early modern society. Hasegawa Tōhaku is one of the greatest painters of this exciting period in Japanese history. His reputation rests on his byōbu, which are folding screens typically formed by five to six jointed panels, and by his foundation of the Hasegawa school with many followers and imitators.

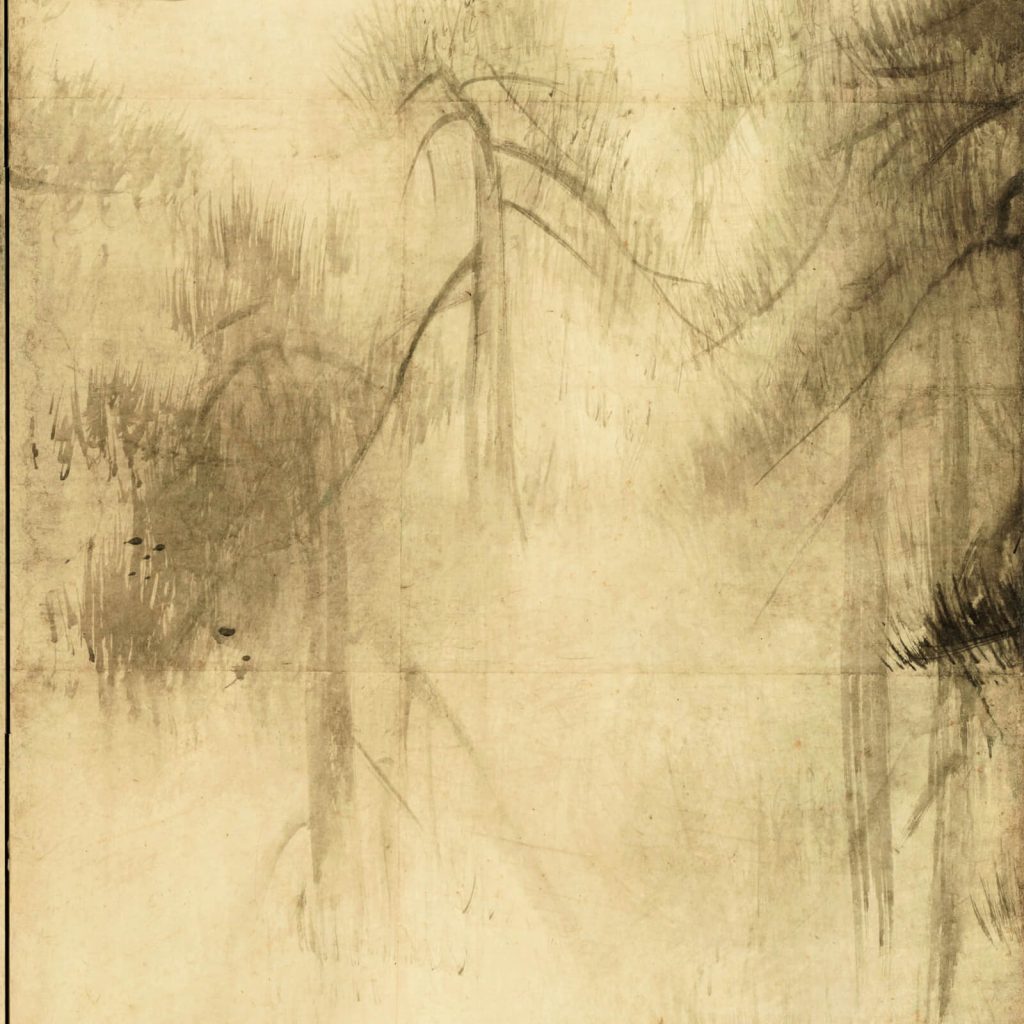

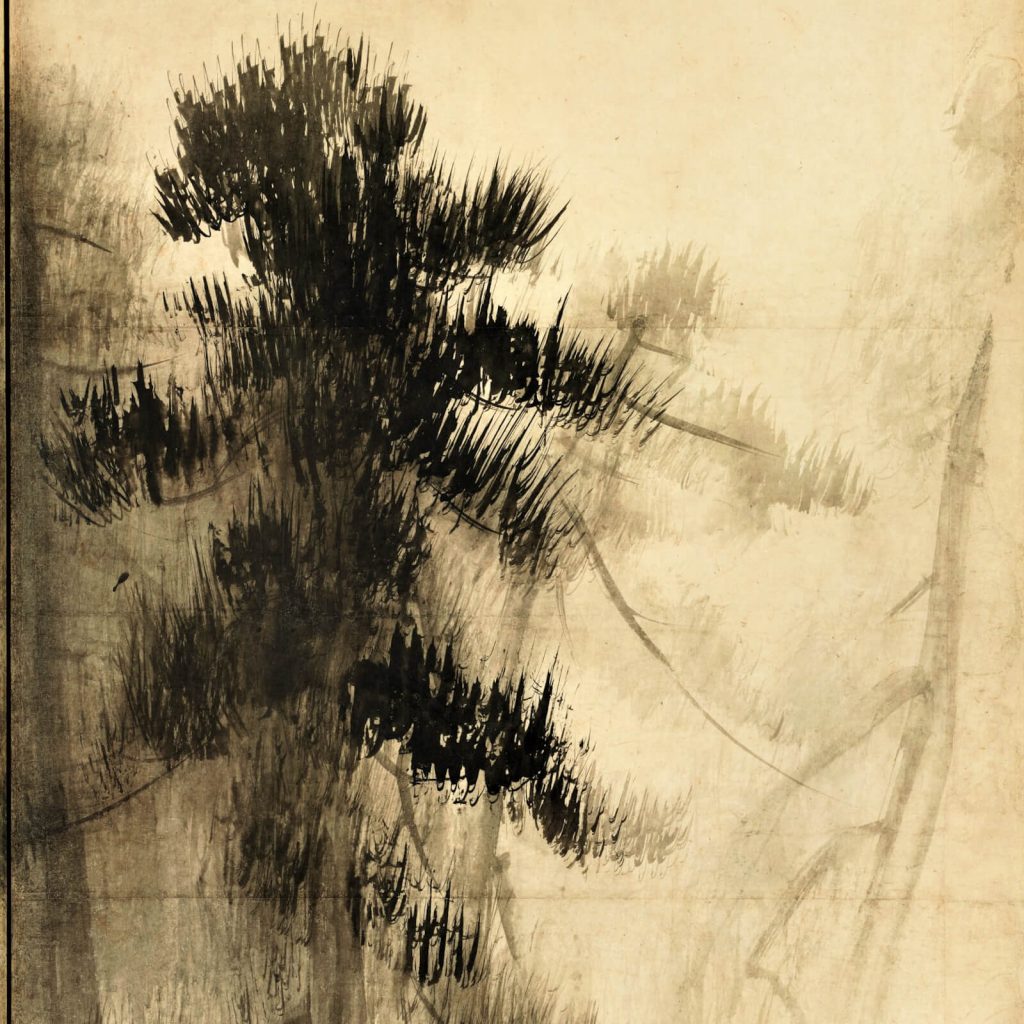

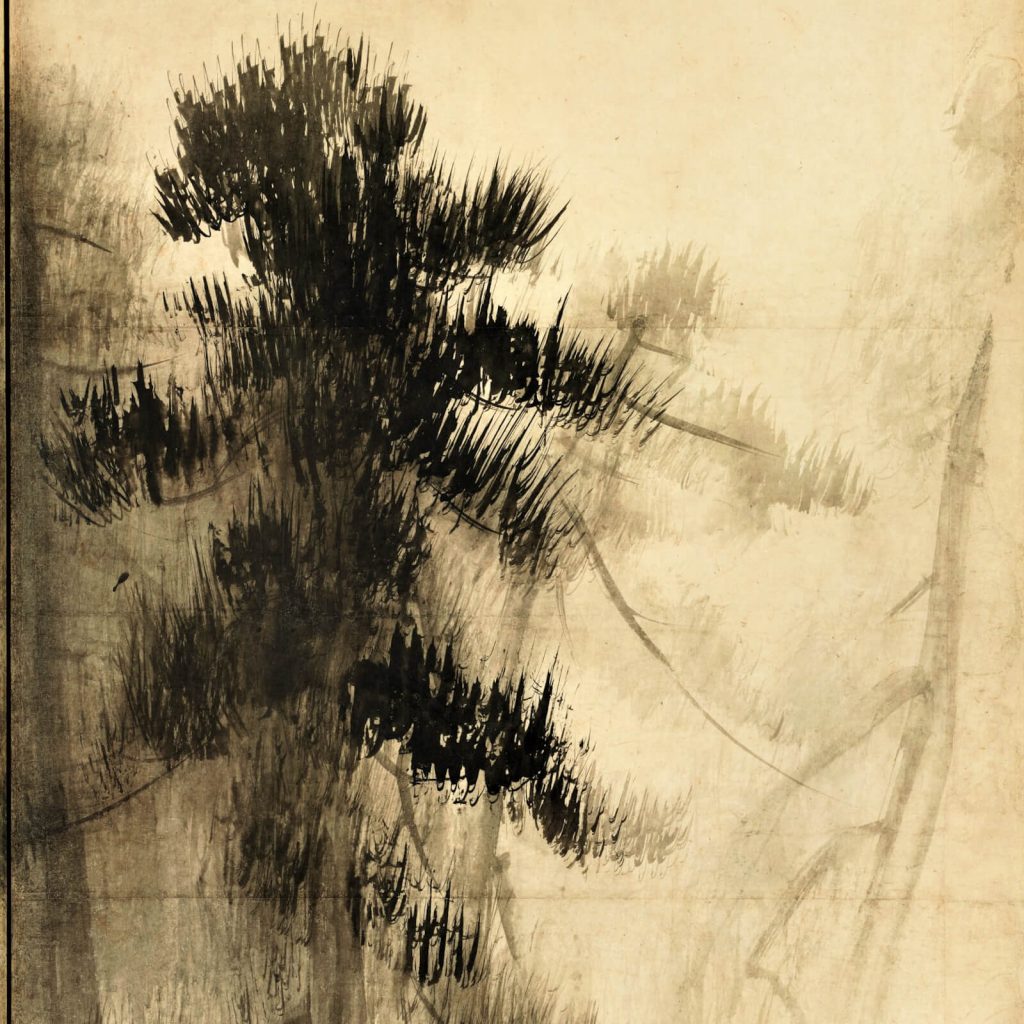

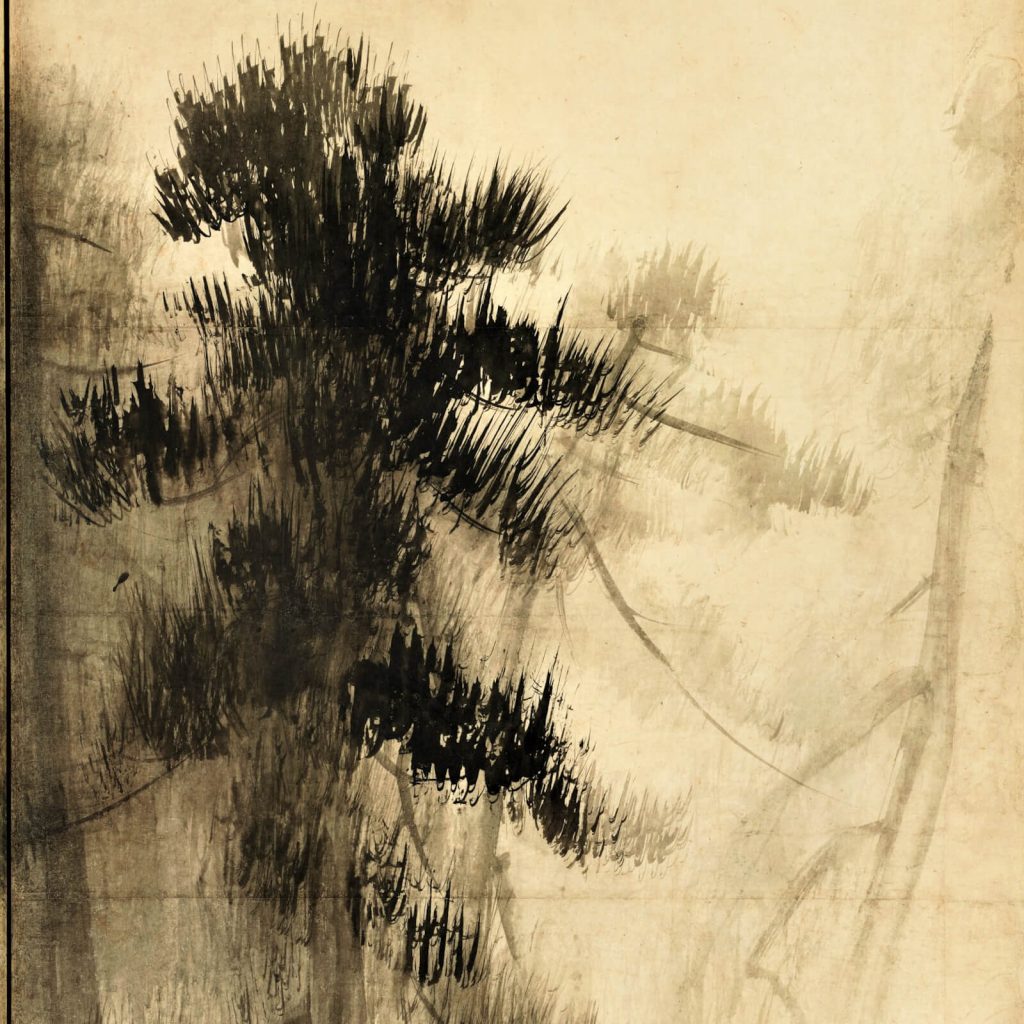

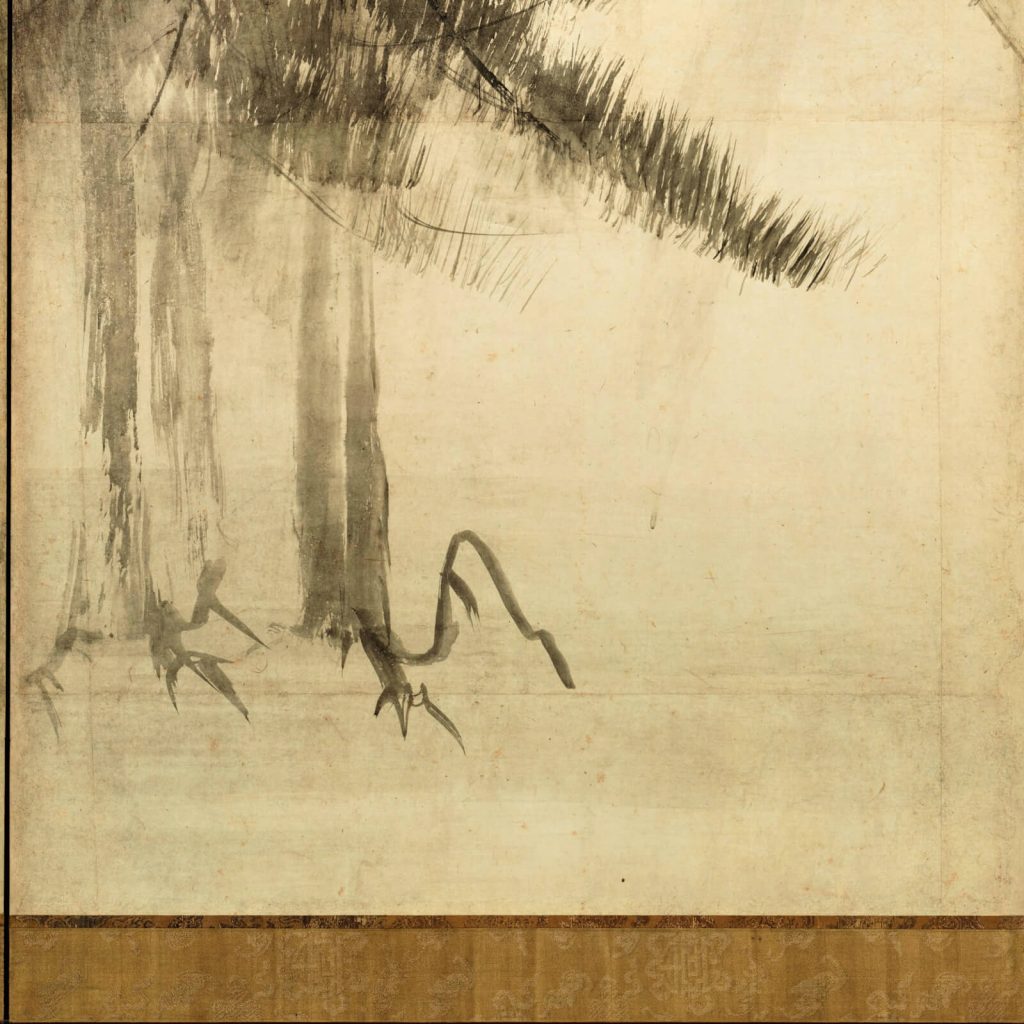

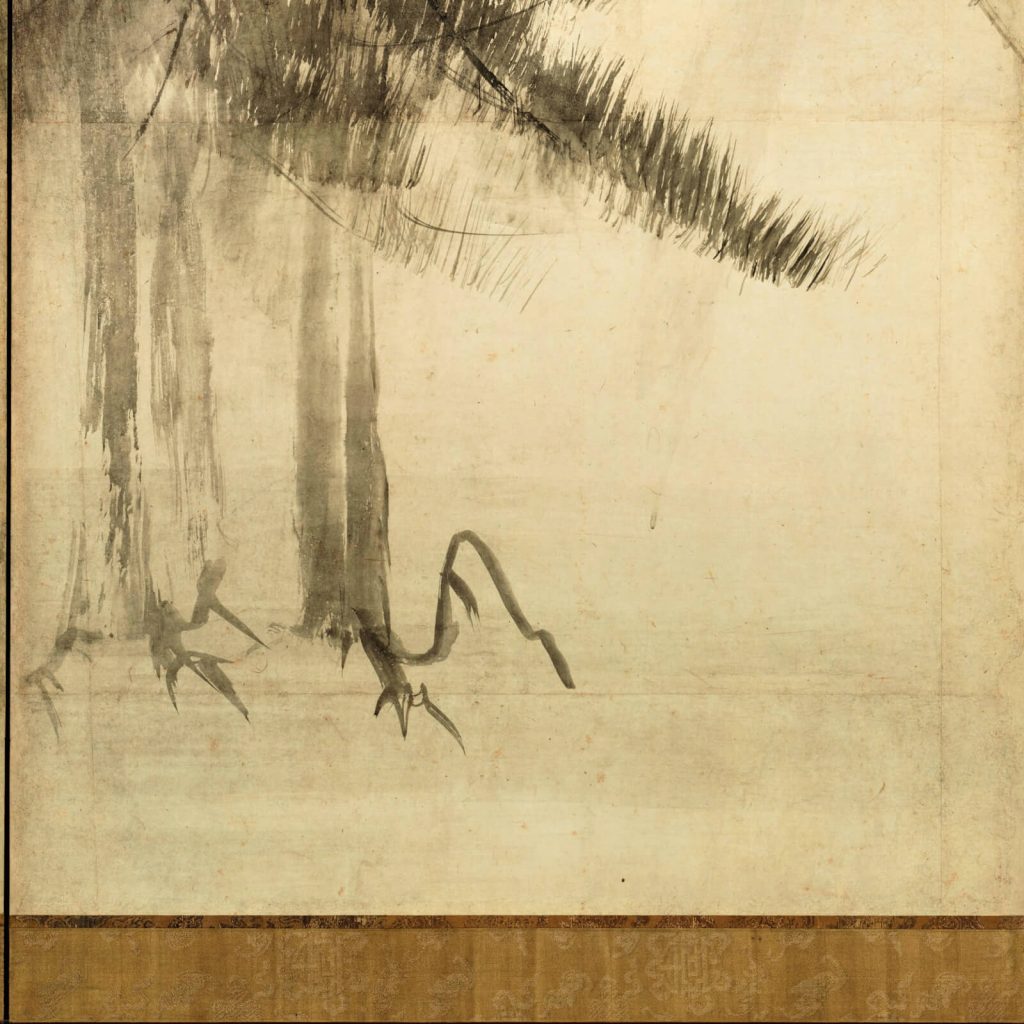

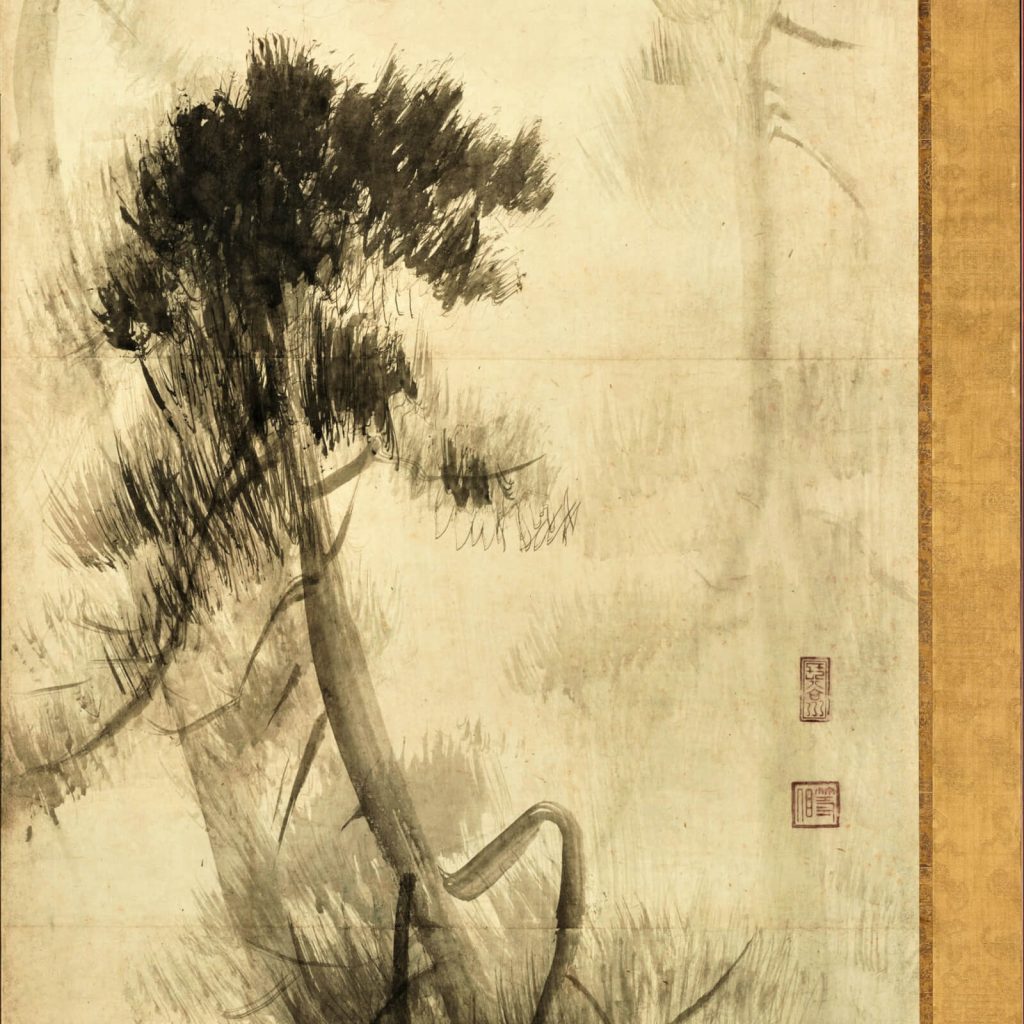

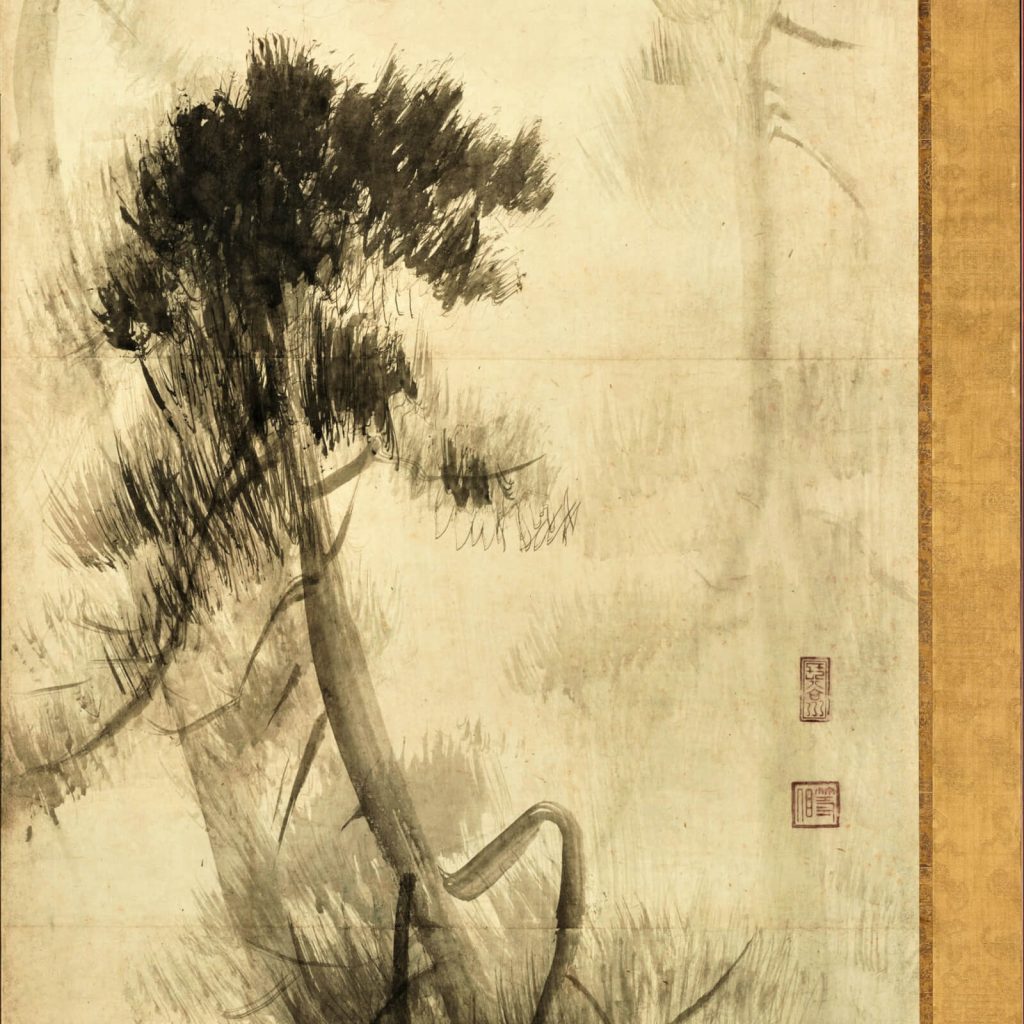

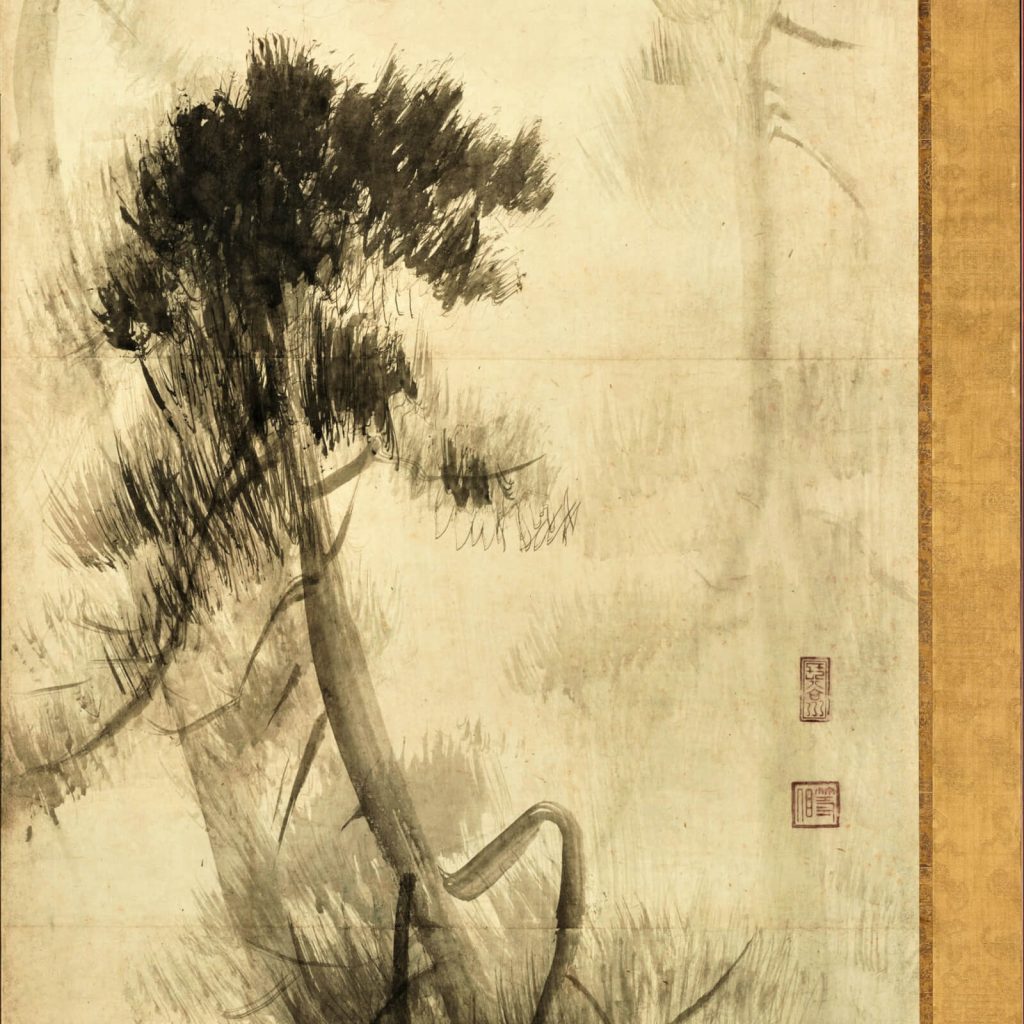

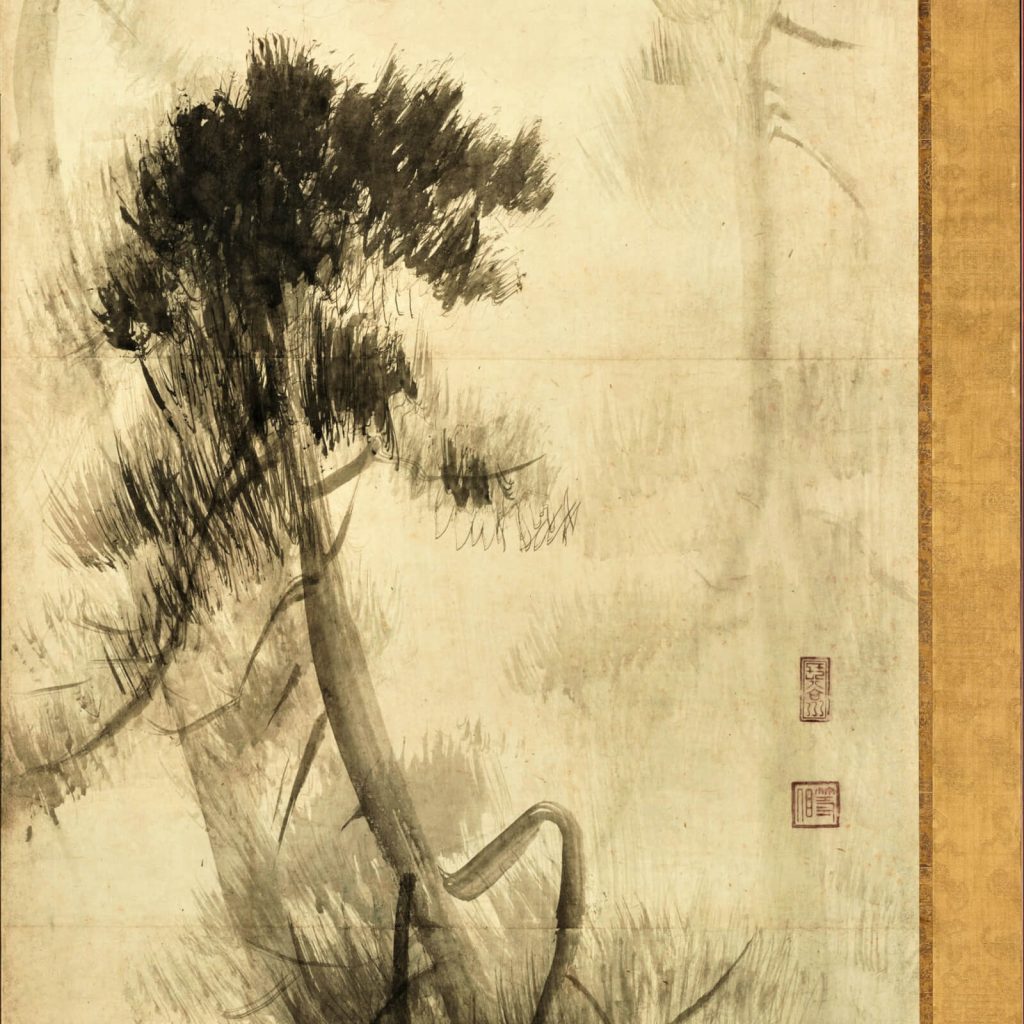

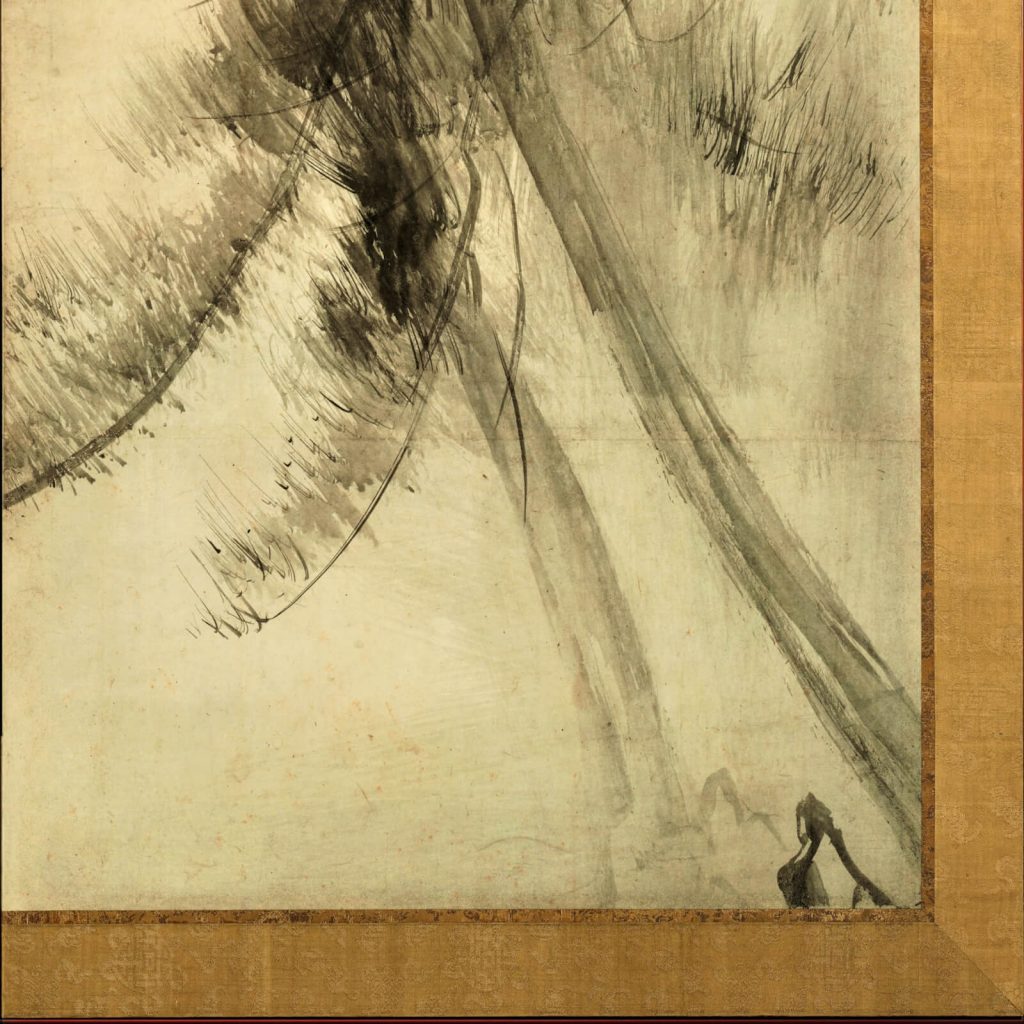

Hasegawa Tōhaku’s Pine Trees is a large byōbu with six panels and measures 5’ 1” high by 11’ 4” wide (157 cm x 356 cm). It is one of a pair that would have been the left partner of the set. Pine Trees is constructed from Indian ink on paper attached to wooden frames. It depicts a grove of pines shrouded in mist with faint snow mountains in the distance. The trees emerge and recede into the heavy atmosphere of cold moist air. Some of the trees, such as in the far right foreground, tilt diagonally, suggesting the uneven terrain of the scene. Some of the trees, as in the background of the third panel, have a blurred outline suggesting the swaying in a blowing wind. The rhythmic swaying of Pine Trees echoes the Noh dance, a classical Japanese dance-drama, which was extremely popular during the Momoyama period.

Hasegawa Tōhaku was a protégé of Sen no Rikyū, the most famous tea master and Zen practitioner of the time. The aesthetics and techniques of Zen are influential and felt throughout Pine Trees. The painting’s monumental scale, minimal elements, and monochrome ink all combine to create a dramatic visual impact that is atmospheric, calm, and meditative. Like the Japanese tea ceremony, Pine Trees and Zen promote the cultivation of the mind and spirit.

Despite using only one material (black ink) to paint Pine Trees, Hasegawa Tōhaku creates a wide variety of effects through mixed combinations of brush stroke lengths, intensity, and moisture. For example, the foreground tree of the third panel is a composition of short, bold, and dry brush strokes. It creates a dark silhouette that has a clarity of form and implies its visual proximity to the viewer, hence it is in the foreground.

However, other trees within Pine Trees have an opposite combination of lines. Like the trees in the second panel, they have a composition of long, pale, and wet brush strokes. These trees are almost formless through their muted silhouettes and minimal details, thereby suggesting their visual distance from the viewer, hence in the background. The different intensities of ink created through different washes or dilutions suggest the different light intensities found in Pine Trees. The dark and dense are in the foreground, with the light and sparse in the background. Hasegawa Tōhaku’s brush strokes vary from long-and-slow to short-and-quick, but they maintain intentional and methodical placement. They present the confidence of a skilled master painter.

Hasegawa Tōhaku painted Pine Trees in late 16th century Japan. Inspiration and influence can be found in earlier paintings, especially from Chinese artist Muqi at the end of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), which were accessible to Hasegawa Tōhaku through contemporary Japanese collections.

Muqi was a 13th-century Chinese Chan (Japanese Zen) Buddhist monk who painted landscapes of immeasurable skill and serenity. The idea of opaque mists enveloping shrouded forms was already known by Muqi, but Hasegawa Tōhaku developed the idea with a more restrained and reserved style. The forms of Pine Trees are easily a single element of Muqi’s mountainous landscapes, but it was in Hasegawa Tōhaku’s genius to take a single artistic motif and develop it into the principal subject of a large painting. Hasegawa Tōhaku was revolutionary in this concept and reflects the minimalist aesthetic so often associated with Japanese Zen. Hasegawa Tōhaku also further enhanced the motif by using very glossy ink on dull matte paper. The visual contrast of gloss and matte adds a crispness to the composition, almost implying the crisp pine scent cutting through the chilly air.

Pine Trees by Hasegawa Tōhaku is a wonderfully complex painting despite its simplistic first impressions. It is also unusually restrained compared to most paintings of the Momoyama period when gold foil backgrounds were predominantly used. The lack of gold prompts some historians to question if Pine Trees is not a preparatory sketch for a lost or undiscovered final version. However, its lack of gold makes it truly unique and more appealing to our minimalist styles today. The Tokyo National Museum, where Pine Trees is currently housed, declares the painting to be a national treasure. After exploring this painting, anyone can agree that Pine Trees is indeed a treasure.

10,000 Years of Art. London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2009.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Hasegawa Tōhaku.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

“National Treasure Gallery: Pine Trees.” Exhibitions. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!