Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

The focus of Käthe Kollwitz’s art is the human being. Above all, a compassionate, humane outlook is characteristic of her approach. She was mainly concerned with the expression of emotions. Kollwitz used heads and hands to symbolize deep thought and intense emotion. Today you will find out why her work belongs to the present, although the occasion in which it was made is a thing of the past.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was born in Königsberg in East Prussia. She lived and worked in Germany during a very hectic time of World War I and died exiled in Moritzburg, Saxony at the end of World War II. Since she publicly opposed Nazism, she was forbidden to exhibit or sell her work.

In 1884 Kollwitz began artistic studies at the Zeichen- und Malschule des Vereins der Künstlerinnen in Berlin with the encouragement of her father. Soon, she realized that her genuine talent lay in graphic media, in monochromatic graphic techniques. After that, she took up etching in 1890 and abandoned oil and canvas for good.

In her early period, Kollwitz preferred the technique of etching but later turned almost entirely to lithography – except for an interlude when she saw the woodcuts of Ernst Barlach in 1920 and self-critically concluded that most of her lithographs were not good and that she should try to find her way in woodcuts. Additionally, she produced sculptures – the majority of them in the 1930s and early 1940s– but she is best known as a printmaker.

Lithography is a technique where everything is reduced to the essentials. With this technique, she liberated herself from the necessity of defining every detail. Her work is full of difficult themes of poverty, infant mortality, violent rebellion, workers of the rural and, later, the urban proletariat. However, these subjects fascinated her: she found them to be beautiful. Later she became acquainted with the difficulty and tragedy of proletarian life and wanted to make an impact with her art. Therefore, she created art with a social purpose:

I am satisfied that my work has a purpose. I want to function in the present time…

She followed her own figurative style and socially engaged themes.

In her entire work, there are almost no backgrounds such as landscapes or interiors. The hands and faces, which are out of proportion in her figures, became the center of expression. Hands provide both comfort and protection: they are overemphasized, prominent, strong, and large.

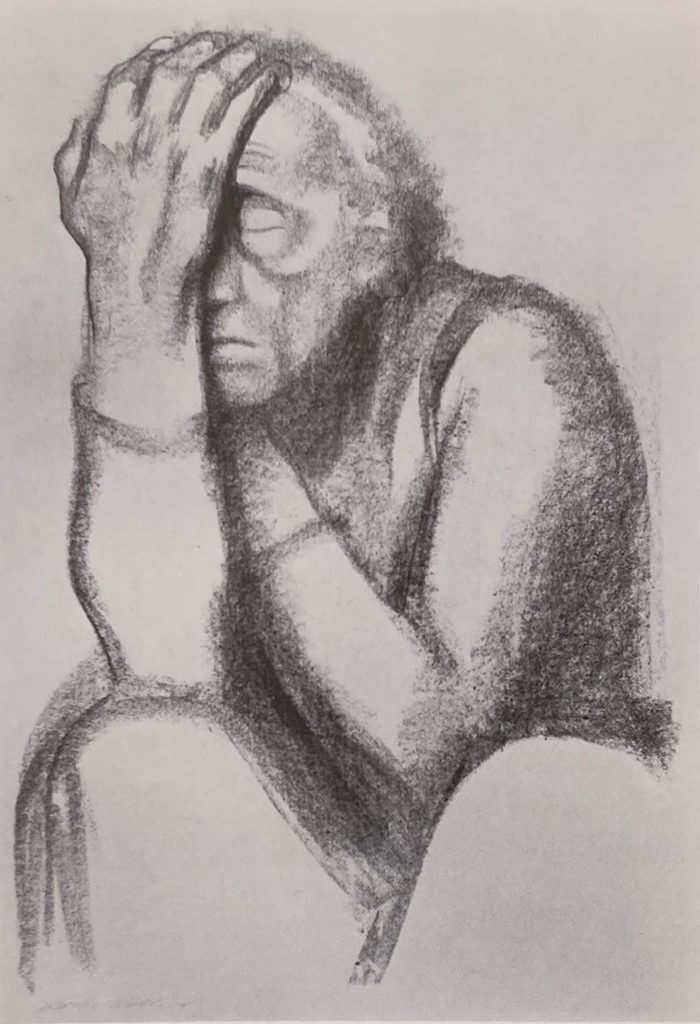

Her self-portraits are especially powerful. In the Self-portrait with hand to forehead from 1910, she combines head and hand together to convey tension and anxiety, emphasized by the deeply contrasting light and shade. Her husband and sons thought that this intense image with grave expression didn’t look like her, but it was a reflection of her soul, an expression of compassion for her fellow man.

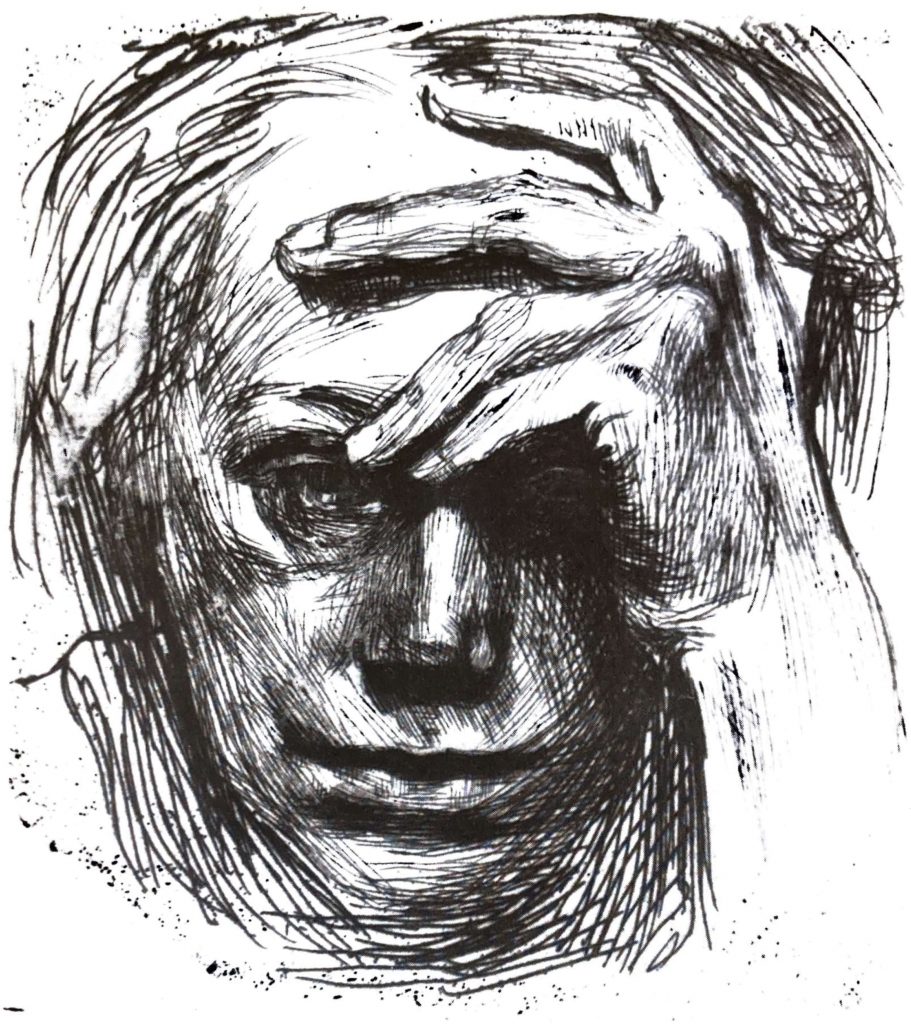

For Käthe Kollwitz, the self-portraits were “a visual form of conversation with yourself.” Moreover, she created hardly any full-length self-portraits. When presenting other figures, she also focuses on the upper body and increases the role of the hands. In Woman Thinking, a lithograph from 1920, an oversized right-hand covers half of a woman’s head. Her eyes are closed. The figure is modeled almost sculpturally, with bold, strong lines. The motif of the hand on the head recalls Rodin’s The Thinker. Kollwitz visited Auguste Rodin twice during her stay in Paris in 1901 and 1904 and admired his work.

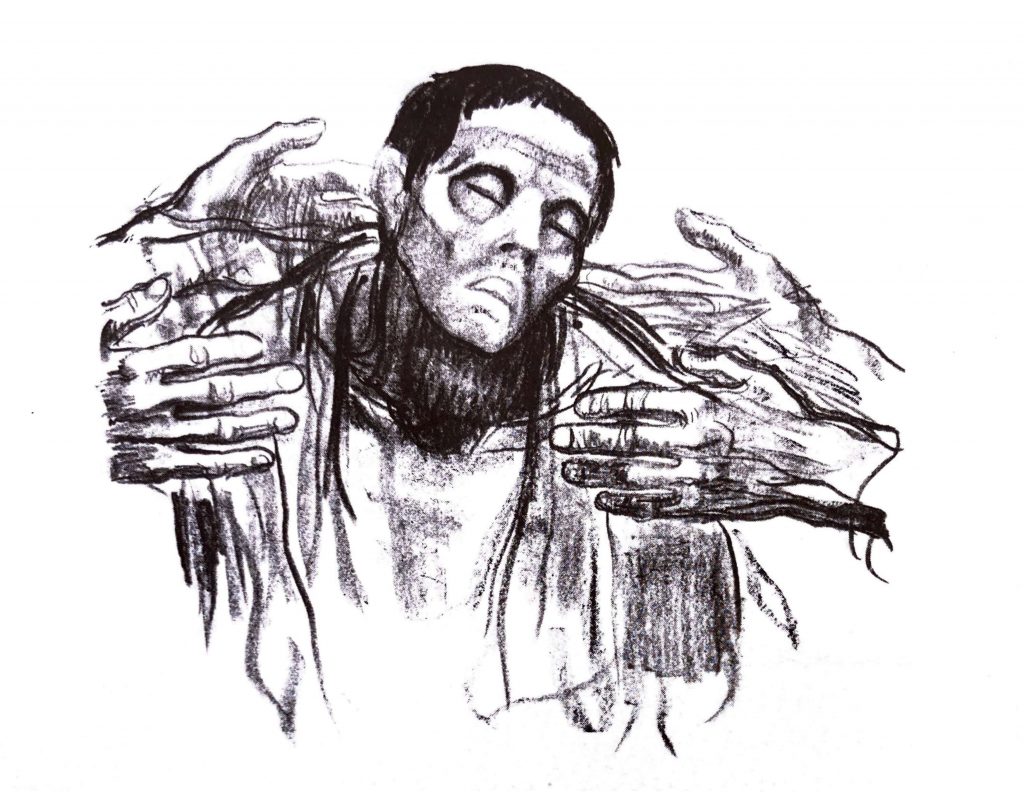

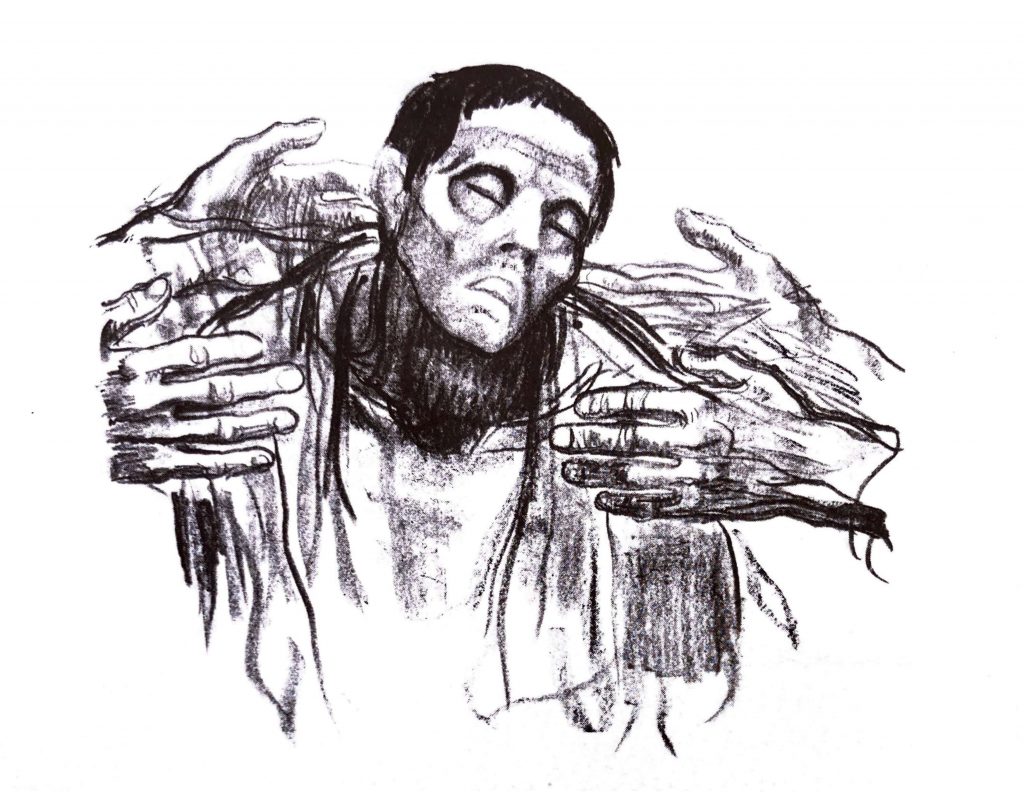

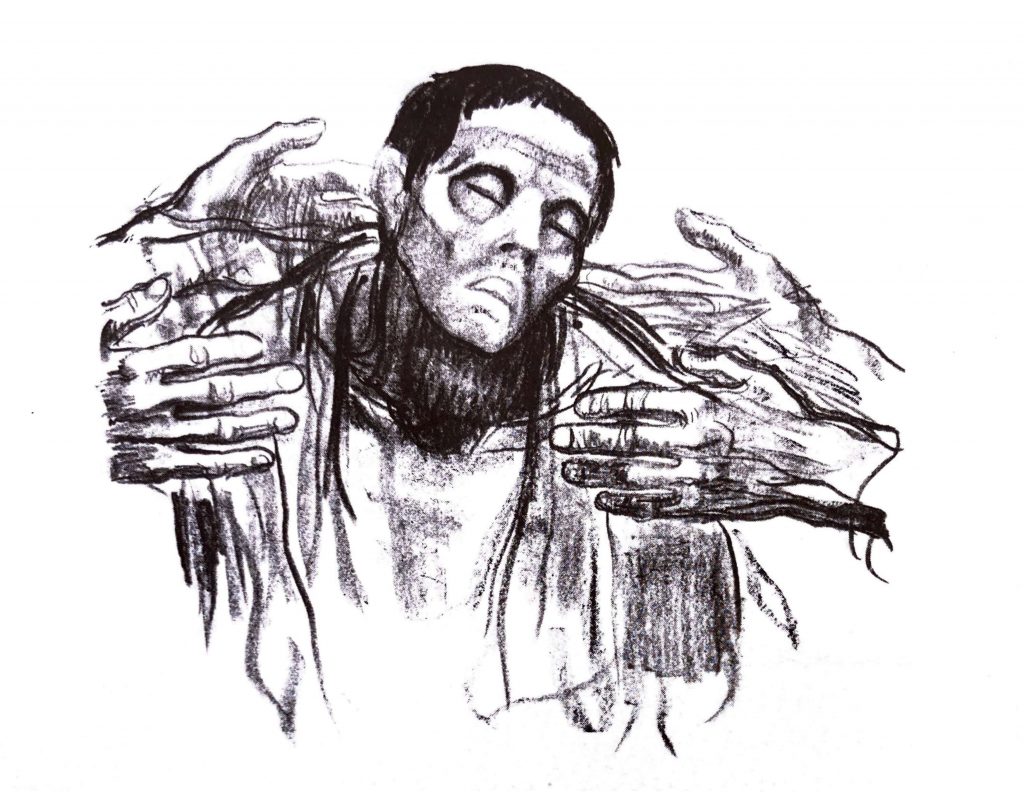

The lithograph Help Russia was published as a poster when Kollwitz was working with the communists for the relief of the terrible famine in Russia. This occasion dragged her into politics quite against her will. A man with gaunt cheeks and sunken eyes is breaking down and his hands are stretching out to help him. With this poster, Kollwitz gives the tragedy a human face. This is one of her many works that was created as a protest against social injustice and suffering.

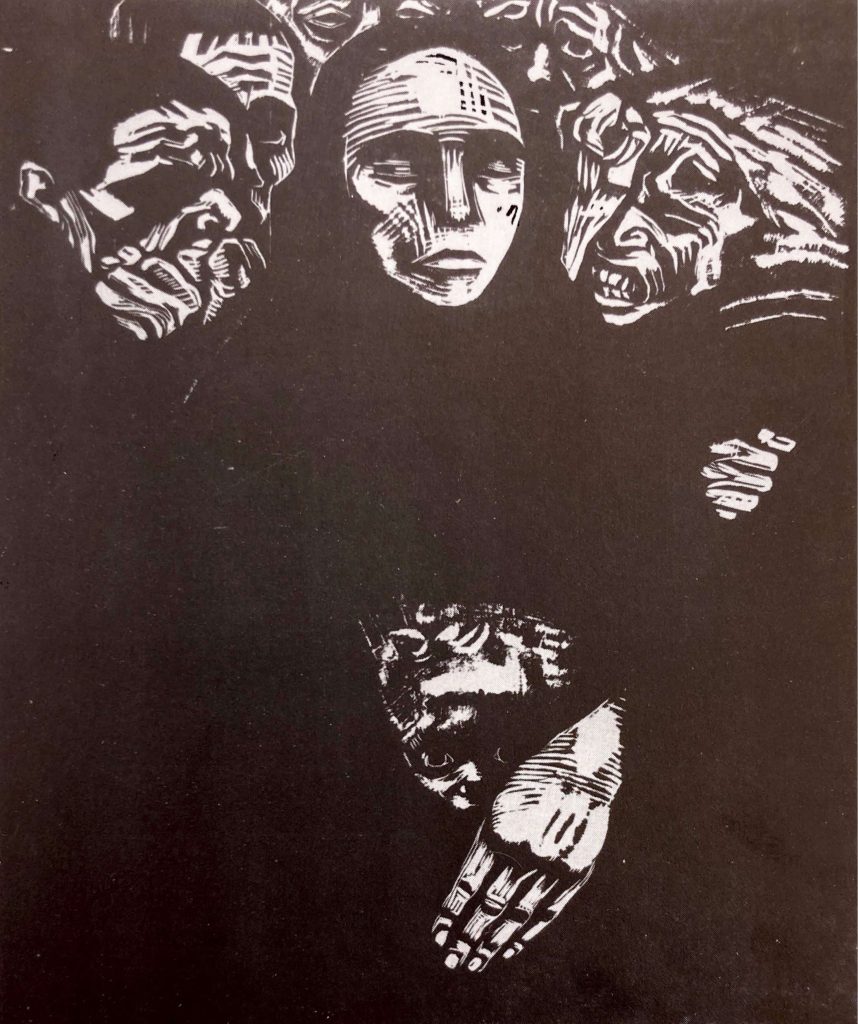

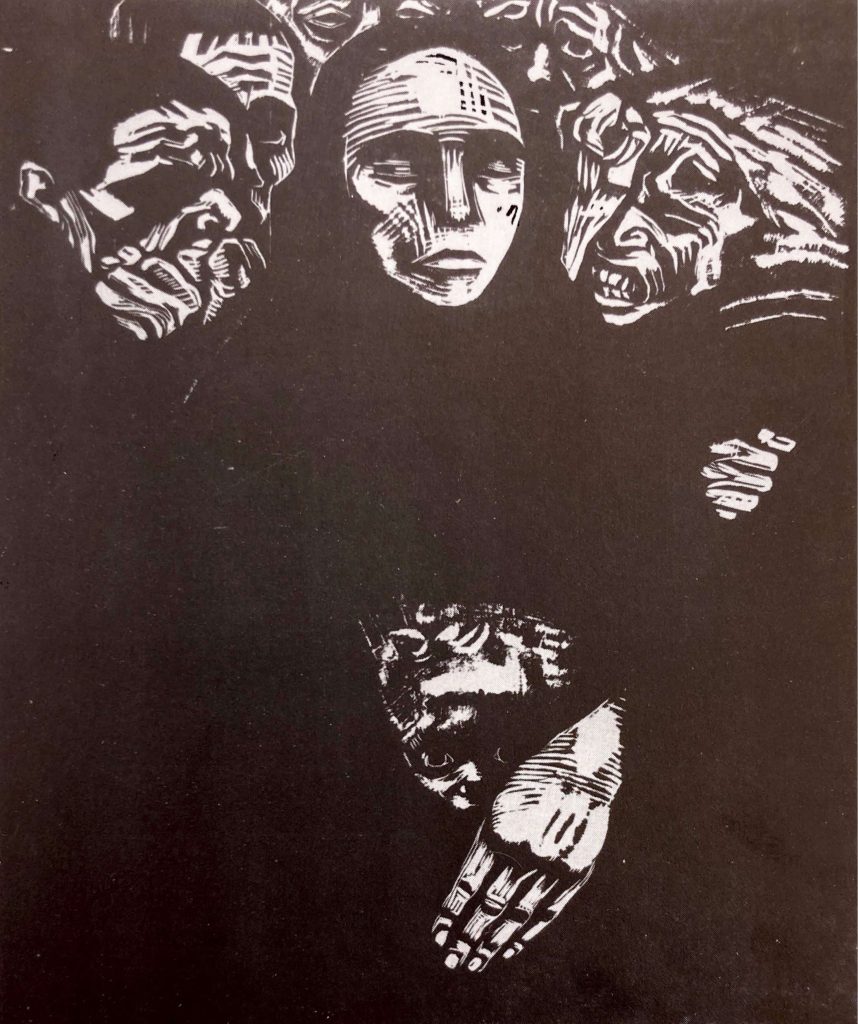

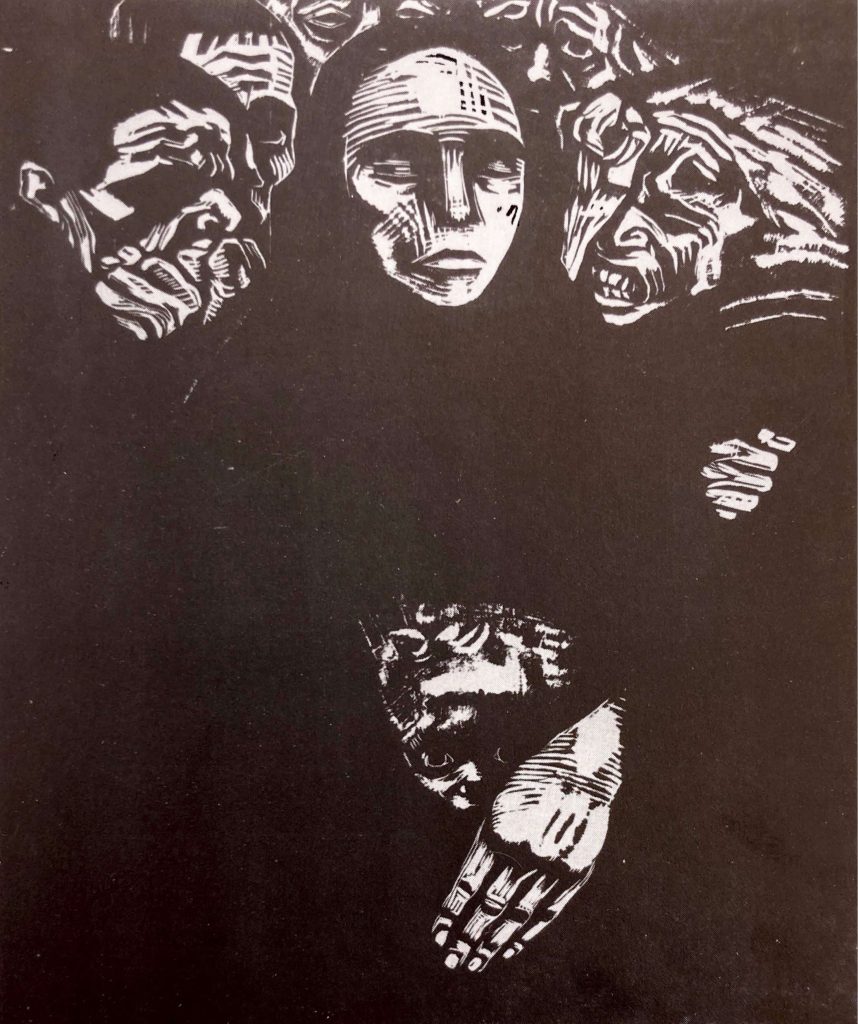

Käthe Kollwitz was constantly reconsidering her artistic work. As the results often didn’t satisfy her, in 1920 she asked herself if she should start all over again and try woodcut. The People is one of the seven prints of the series War done in 1922-1923. The series deals with life in the years of World War I and is a universal expression of antiwar sentiment.

A woman is at the center, in iconic form. Five male figures surround her. Her eyes are struck with grief, her face is ageless. In the lower half of the image, a child comes out of the darkness of her clothes. She protects the child with her hand. Again, Käthe Kollwitz uses faces and hands to deepen the emotive effect. Different expressions on the faces of men together with the forms of their hands represent the victims of war, their mental state, fears, and sorrow.

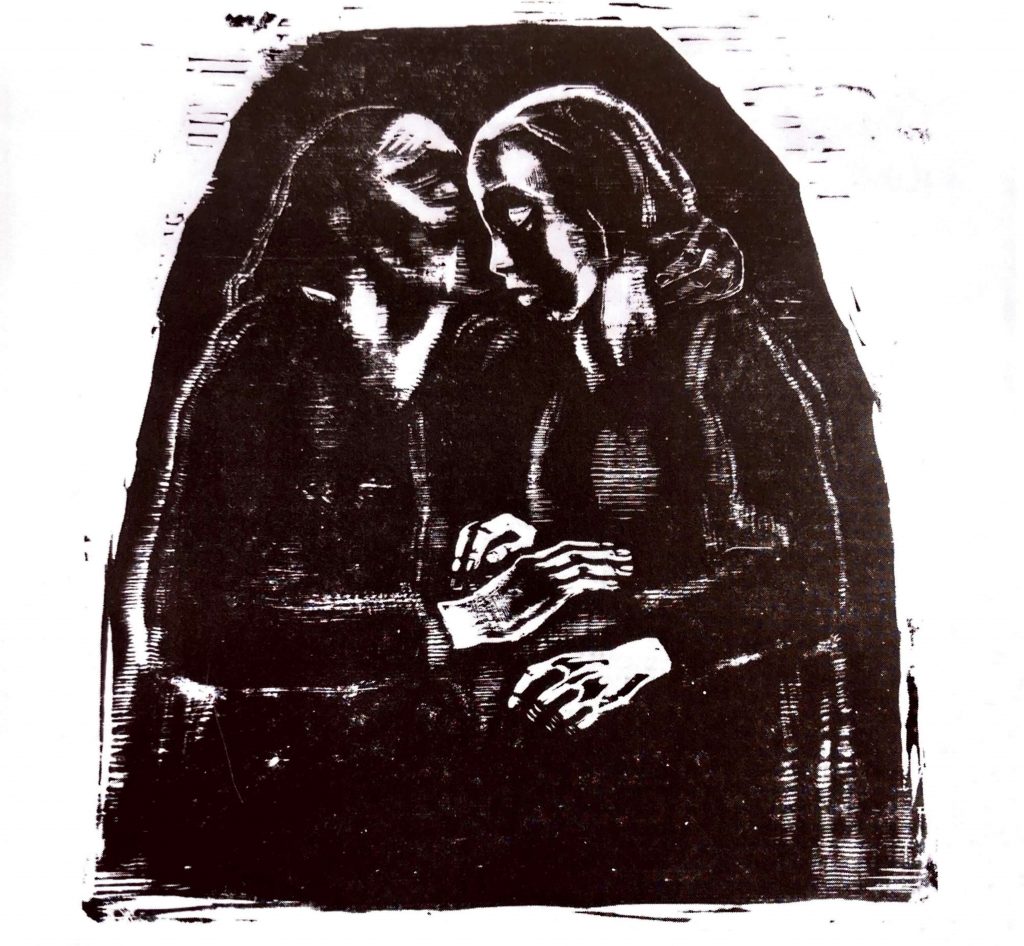

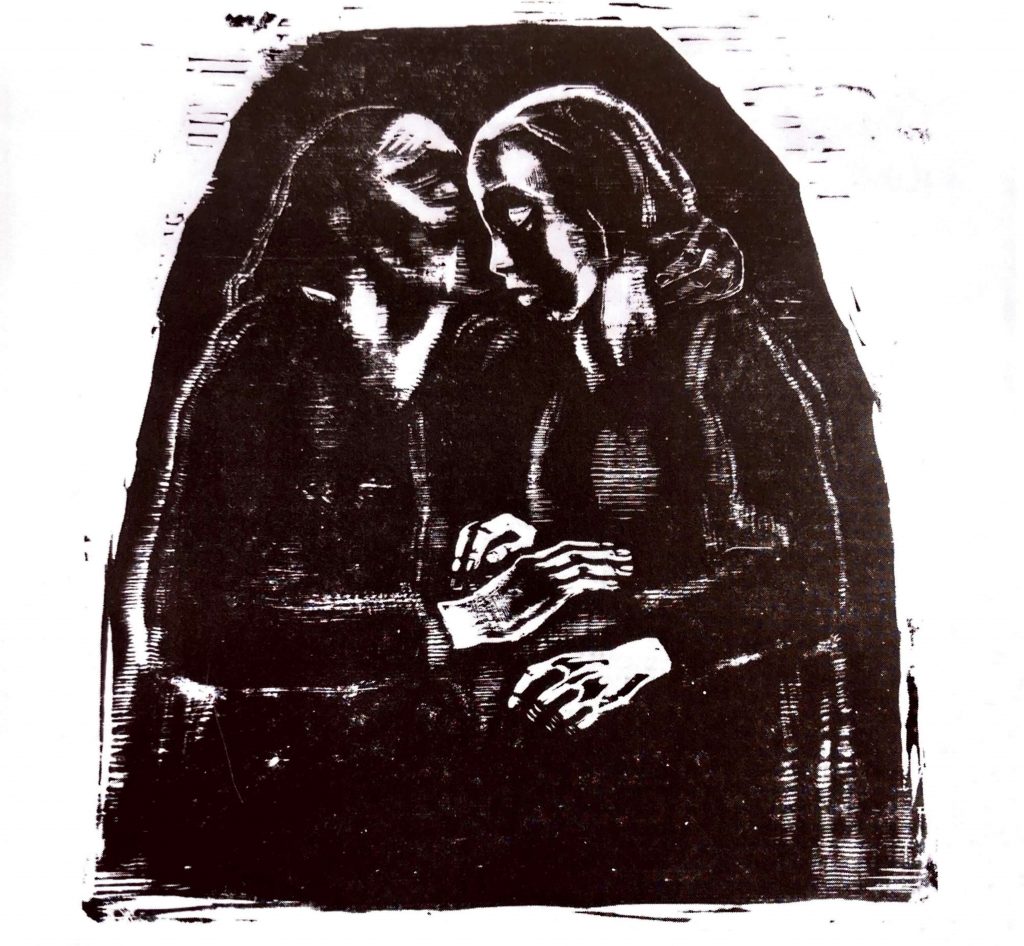

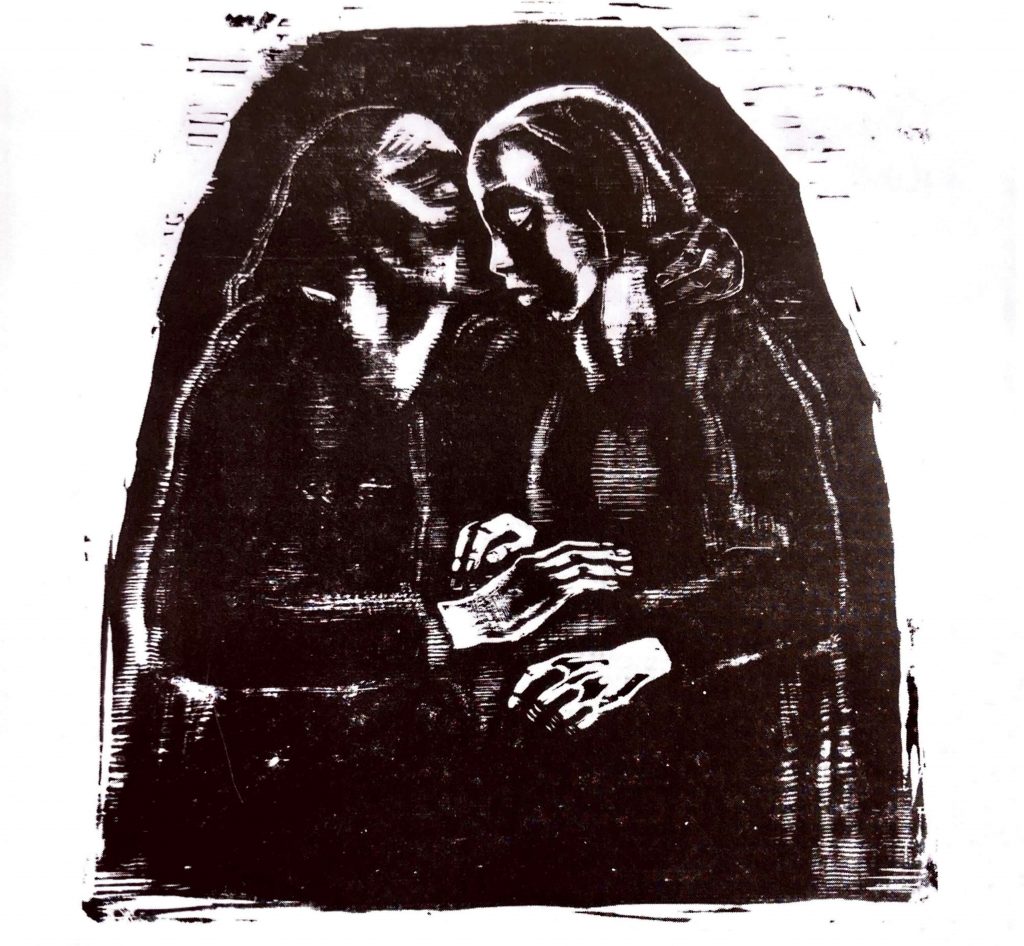

The monumental and sculptural woodcut of Mary and Elizabeth from 1928 shows two working women, simply dressed. It is a traditional theme in a traditional pyramidal composition but represented the time and situation in which Kollwitz lived. The black, surrounding the figures and in their clothes, unites them. The older woman hugs the pregnant young girl and says something in her ear. From the way the light falls it is obvious that Käthe Kollwitz is again focused on faces, hands, and gestures in her art.

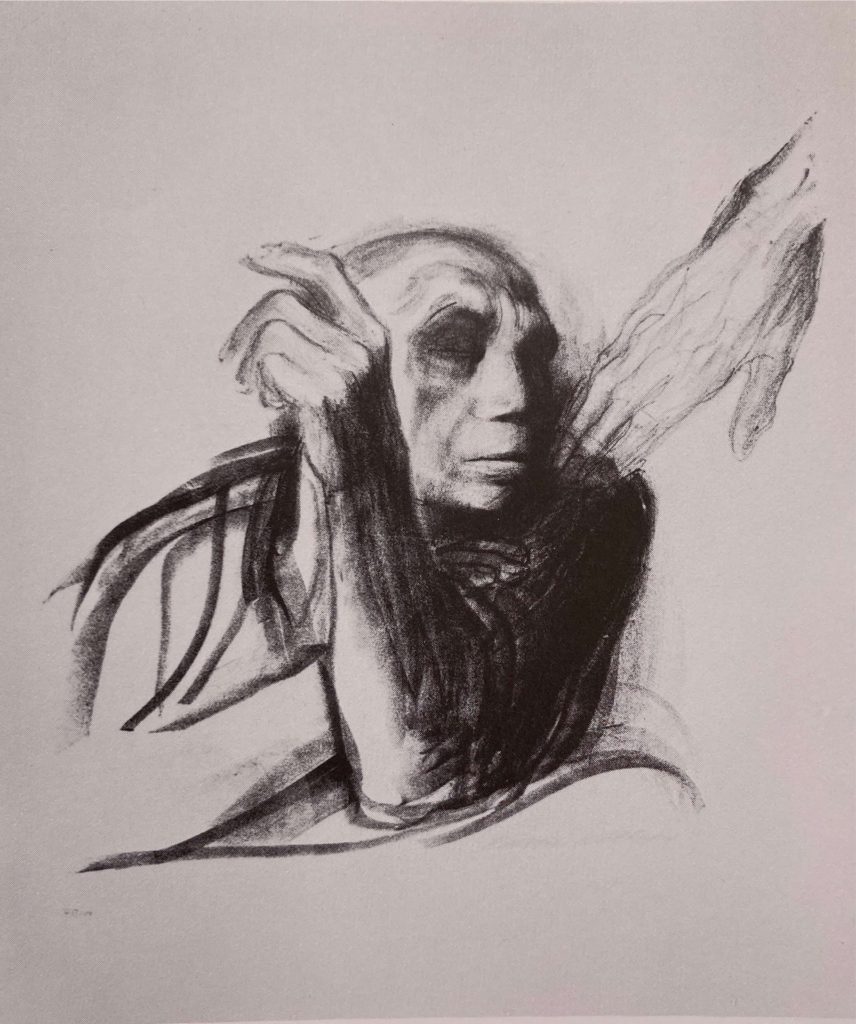

Death as a theme was a consistent motif in Käthe Kollwitz’s art throughout her career. Her lithograph The Call of Death is one of eight prints of the series Death, which was executed between 1934-1937. It marks the end of Kollwitz’s graphic work. It is actually her self-portrait in which she instinctively raises her hand to grasp Death in the form of a disembodied human hand, which gently taps her on the shoulder. Her eyes are closed in peaceful expectation of this long-awaited visit. She was deeply affected by the death of her youngest son in World War I and her grandson during the second war. With her art, she explored her own grief.

Kollwitz made most of her sculptures during the 1930s and early 1940s when she was forbidden to exhibit or sell her work. The bronze Lament presents the head of a woman, who bears the features of the artist. Her oversized, strong hands are placed over the mouth and an eye. Under the impression of her friend and colleague Barlach death, the sculpture shows bewilderment, pain, and sadness as well as a condemnation to silence, as she was prevented from presenting her work in public.

Käthe Kollwitz: Engravings Drawings Sculptures. Exhibition catalog. Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations Stuttgart, 1982.

Prelinger, Elizabeth. Käthe Kollwitz. Exhibition catalog. National Gallery of Art Washington DC & Yale University Press New Haven & London, 1992.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!