Curating during Lockdown

Opening ten years after her death, Radical Beauty examines Helen Frankenthaler’s revolutionary approach to the woodcut, positioning her as one of the medium’s great innovators. What was the biggest challenge in putting the exhibition together?

“The biggest challenge in putting together this exhibition was curating through the pandemic. We had to find new ways to work remotely with our New York partner, the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. And had to manage changing schedules and pauses to activity brought about by the different lockdown phases in the UK and US. But the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation were brilliant and so supportive throughout. We’re very proud to have opened the exhibition at the Gallery this autumn.”

Trailblazer Frankenthaler

Overall, Frankenthaler found new dimensions in the medium of wood block and experiments with different orientations and color ways, as well as a variety of new tools and methods. The collection at the Radical Beauty exhibition is simply breath-taking. The soft tones and unique colorings flood the gallery with such a warm feeling while textural qualities, such as the wood grain within the paint, make the prints utterly compelling. What one thing would you want visitors to take away from the experience of seeing the exhibition?

“We’d like visitors to see how Frankenthaler turned woodcut printmaking on its head. In her hand prints become painterly, expansive, fluid. And importantly that through this lesser known body of work we can see her through a new lens and understand why she is such an incredible and enduring creative force.”

Radical Techniques

Frankenthaler defies the limitations of what is often considered the most rudimentary of printmaking techniques; she found new dimensions to the medium, experimenting with different orientations and color ways, and a variety of new tools and methods.

“The combination of Frankenthaler’s inventive mind and intrepid approach is most unique about her innovative attitude to printmaking. She threw out the rule book for printing and made it yield to her creative language through audacious experimentation.”

Radical Beauty brings together 36 works which reveal her enormous diversity in scale and technique. Challenging traditional notions of woodcut printmaking, Frankenthaler’s “no rules” approach is explored thematically. The descriptions at the exhibition are highly informative. They explain the techniques Frankenthaler used and pioneered. In the exhibition the proofs of Essence Mulberry show a real insight into the entire process of Frankenthaler’s radicalism.

Experimenting with a Traditional Technique

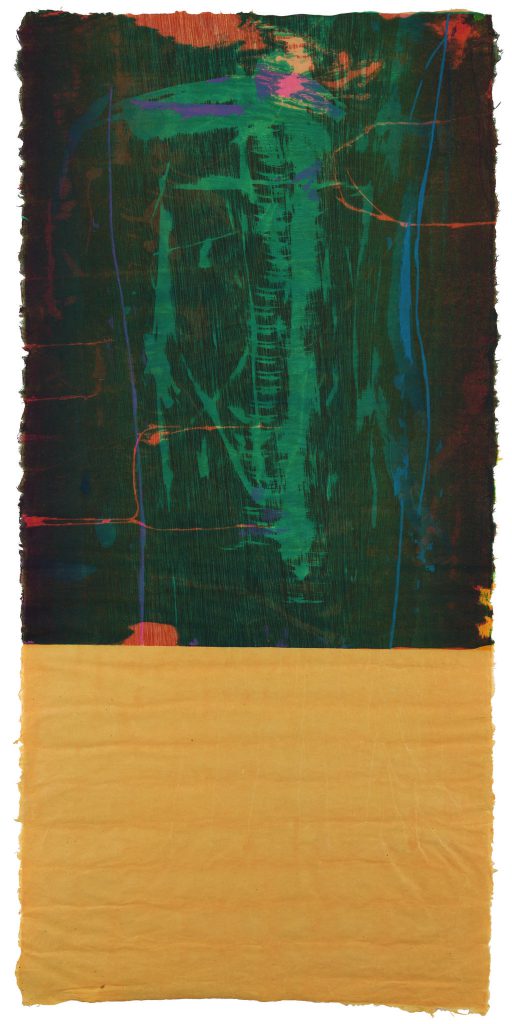

One way in which Frankenthaler really pushed her practice was through collaboration. For example, the description for Cedar Hill explains Frankenthaler’s collaboration with the Ukiyo-e printmakers in Kyoto, Reizo Monjyu and Tadashi Toda. In what ways are Frankenthaler’s woodcuts similar and different from the traditional Japanese styles?

“She combines traditional technique with her experimental approach. You can see this in Snow Pines which has a very contemporary sensibility but was a work that she began by building up layers of green and blue using the Ukiyo-e tradition. In this way she is able to celebrate the beauty of tradition but also bring new qualities that merged this practice with hers.”

Madame Butterfly

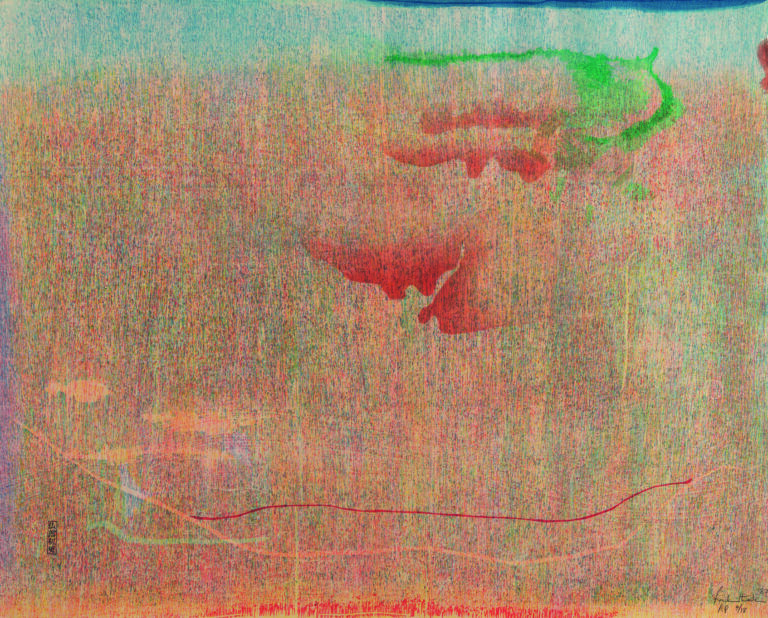

A key focus of the exhibition is the masterpiece Madame Butterfly (2000). The triptych’s light pastel colors and stained marks show Frankenthaler at her most expressive. Madame Butterfly was created in collaboration with Kenneth Tyler and Yasuyuki Shibata from 46 woodblocks and 102 colors. Could you talk a little bit about influence of the 1904 opera, with which the work shares its name?

“Sharing its title with Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly evokes the tragic story of love and heartbreak, that ends in death, birth, and remorse. However, as with many of her works, the print does not reveal a direct connection to its name. Frankenthaler’s ambiguous title offers an invitation to the viewer to bring our own personal interpretations. She conjures up not only the famous opera but also the image of a butterfly wing, Japonisme, the butterfly effect and much more. In this way we as the viewer are involved in this very active meaning making process.”

A Comparison To Monet

As a teaser for gallery visitors (or a treat after coming out of the exhibition) Dulwich Picture Gallery is also displaying a Monet, Water Lilies and Agapanthus (1914-1917), beside Frankenthaler’s Feather (1979) . This provocation makes you draw links between the exhibition and the gallery’s other works. Can you talk a little a bit about how Frankenthaler’s oeuvre complements and comes from the Impressionists and, perhaps, even the Old Master’s that Dulwich Picture Gallery houses?

“Monet was a founding figure in the Impressionist movement and his pioneering approach opened the door for later artists, such as Frankenthaler, to take risks with color and abstraction. By considering Monet’s Water Lilies and Agapanthus (1914–1917) alongside Frankenthaler’s Feather (1979), we can see how both artists harnessed paint to capture the transience of nature. We can also see how both took inspiration from the Old Masters by comparing these two paintings with works in the our collection, from Thomas Gainsborough’s evocation of leaves rustling in the wind to the careful modulation of light and shade of Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window.”