Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

The Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands, holds the second-largest Van Gogh collection in the world. Furthermore, the museum presents masterpieces by modern masters such as Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Pablo Picasso, and Piet Mondrian. However, there would be no museum were it not for Helene Kröller-Müller. She is the woman behind the idea and the museum’s collections.

Helene Kröller-Müller was born Helene Emma Laura Juliane Müller on February 11, 1869, in Essen, Germany. She was born and raised in a wealthy industrialist family. Helene’s father, Wilhelm Müller, owned Wm. H. Müller & Co., a prosperous company that supplied raw materials to the mining and steel industries.

Helene Müller didn’t have much of a connection with art in her early life. She was a bright girl, though. At age 14, she began to question God and her belief in the Bible. At that time, she discovered the ideas of Enlightenment writers and philosophers, especially Spinoza. Consequently, she formulated her life motto: Spiritus et Materia Unum—spirit and matter are one.

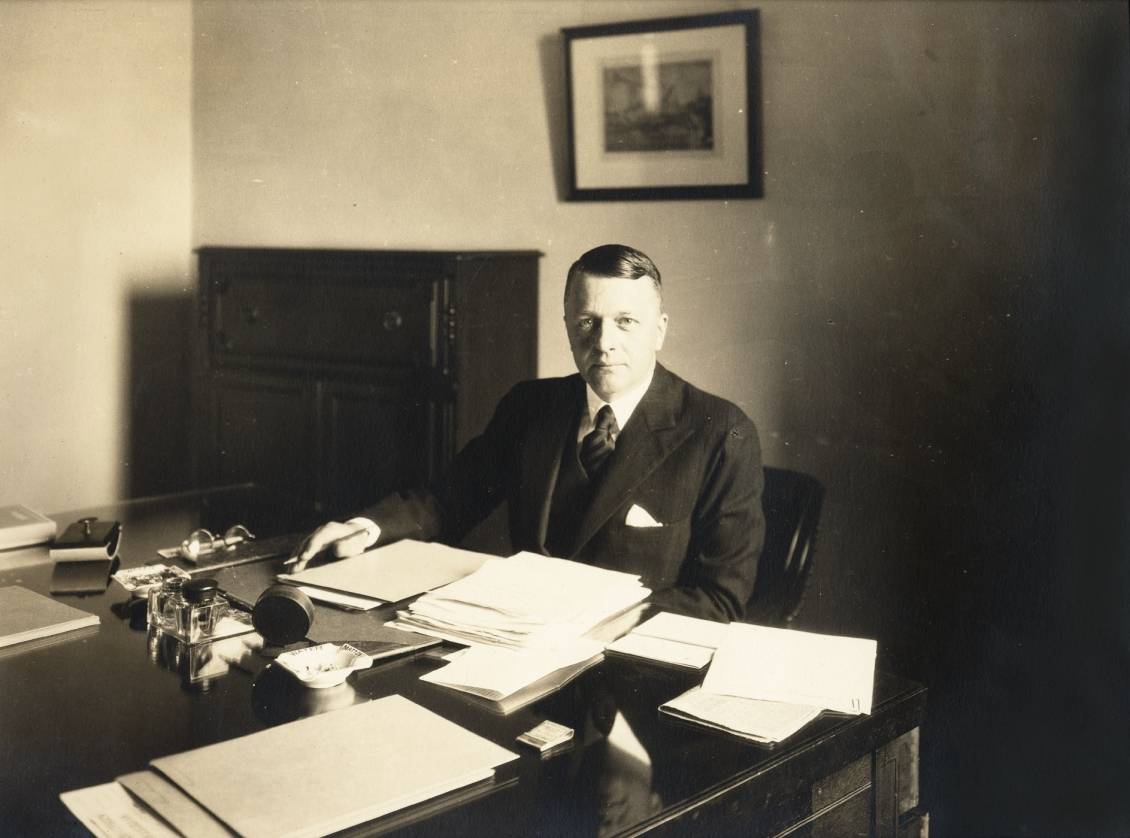

In 1888, upon her father’s request, Helene married the Dutchman, Anton Kröller, who worked for her father. The couple settled in Rotterdam, where Anton was in charge of a branch of Müller & Co. Anton Kröller later became the director of the company. They had four children: Helene (junior), Toon, Wim, and Bob.

Helene Kröller-Müller was one of the wealthiest women in the Netherlands. She lived the life of a merchant’s wife. In 1905, Kröller-Müller and her daughter Helene Jr. began taking art classes from the art educator Henk Bremmer. He introduced her to modern art and taught her how to observe art.

She started collecting art probably because she found a spirituality in it that she couldn’t find in religion. The first work she purchased was It Comes from Afar by Paul Gabriël. In 1907, she hired Bremmer as her personal advisor for assembling an art collection.

Eventually, Helene Kröller-Müller became an enthusiastic art collector. She was also one of the first people to appreciate the genius of Vincent van Gogh. The first Van Gogh works she purchased were Edge of a Wood and Four Sunflowers Gone to Seed in 1908. One year later, she acquired The Sower (after Millet) and Basket of Lemons and Bottle.

In 1906, Kröller-Müller’s daughter and her classmates set up the hockey club ODIS together. Sam van Deventer was a member of the team. After graduation, Anton Kröller invited Van Deventer to work at Müller & Co. Consequently, Van Deventer wrote to Anton, but as he was absent, Helene replied about the company’s opportunities. Van Deventer got the job, and a lifelong friendship began.

Or was it something more? Kröller-Müller’s and Van Deventer’s relationship lasted from 1908 till her death in 1939. They wrote long letters to one another, even multiple times a day when they were far apart. They also spent a lot of time walking together when they were in the same city. The letters, preserved to this day, hint at the true nature of their relationship.

Her relationship with Van Deventer ruined Kröller-Müller’s relationship with her daughter, but not with her husband. Anton Kröller trusted his wife. Eventually, they formed a strange trio. Helene and Sam developed a unique, deep, platonic love through their letters. It is obvious that attraction and longing were present.

Oh Sam, those flames were like arms reaching out to the unattainable light and, like Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, they were burning their own heart just like the fiery ball below, that will keep roaming the earth until it finally surrenders to very, very strong arms that will embrace it firmly.

– from Helene’s letter to Sam van Deventer about a dream. Leo de Boer, “Helene, A Woman Between Love and Art.”

The events around WWI aroused in Kröller-Müller a strong need to help. In 1914, she decided to go to Liège. There, she took care of wounded soldiers together with nuns and nurses at the l’Hôpital des Anglais.

You see, Sam, I can’t sit still and live in a country where war is waged only with pen and tongue, in a sneaky way, while I hear and feel the world stirring abroad. Nor can I sit around doing nothing, while my people fight and suffer.

– from Helene’s letter to Sam van Deventer about the war. Leo de Boer, “Helene, A Woman Between Love and Art.”

Meanwhile, WWI brought Müller & Co. high profits. As a result, Helene Kröller-Müller was able to buy even more artwork. One of her favorites was Renoir’s Clown and Fantin-Latour’s Portrait of Eva Callimachi-Catargi.

On a trip to Florence in June 1910, Kröller-Müller had the idea of creating a museum. From 1913 onward, parts of her collection were open to the public at the Museum Kröller in The Hague. In 1917 she commissioned Hendrik Petrus Berlage to design a great museum on the Veluwe for her collection.

H. P. Berlage began work in 1915 on the design and construction of the St. Hubertus Hunting Lodge, Kröller-Müller’s country residence. Helene Kröller-Müller chose him because she liked his style. Also, she liked the idea that something majestic didn’t have to be built by the aristocracy but by a merchant. Unfortunately, in 1919, Berlage resigned after finishing the lodge building.

Afterward, Helene Kröller-Müller asked the Flemish architect Henry van de Velde to build the museum. The foundations were laid in 1921. Then, the bankruptcy of Müller & Co. and the resulting financial crisis stopped her plans. As a result, in 1928, Anton and Helene created the Kröller-Müller Foundation to protect the collection and the estates.

He no longer envisions the greatness of the concept. He believes the museum won’t be in any proportion to the collection. But the museum will be our greatest legacy.

– from Helene’s letter to Sam van Deventer about her husband. Leo de Boer, “Helene, A Woman Between Love and Art.”

The whole situation shocked Helene Kröller-Müller. Also, she was in poor health, so she recovered in Baden-Baden for some time after. She didn’t give up, though. She called the Minister of Education, Art, and Science and begged him for an audience. She succeeded in convincing him to get help from the State.

In 1935, the Müllers donated their entire collection to the Dutch State. The only condition was that the museum be built in the gardens of their park. The project also provided jobs for many people.

Helene was in her late 60s. Despite this, she visited the construction site daily to supervise the work. Under the care of the Dutch government, the Kröller-Müller Museum was opened in 1938. Shortly after, in December 1939, Helene Kröller-Müller became sick. She died on December 14, surrounded by her loved ones.

Helene Kröller-Müller’s goal was to create a collection “for the benefit and enjoyment of the community.” She focused mainly on French and Dutch art, with an extremely important position reserved for Vincent van Gogh. She collected more than 90 Van Gogh paintings and 185 drawings. This is the second largest collection of Van Gogh’s works in the world (the first is that of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam).

The Kröller-Müller Museum is located on more than 75 acres (300,000 m2) of forested country estate in the Hoge Veluwe National Park. It is encircled by the later-added sculpture garden, one of the largest in Europe. Over 160 sculptures by iconic artists, from Aristide Maillol to Jean Dubuffet, Marta Pan to Pierre Huyghe, are distributed throughout the garden.

I believe in the perfection of everything that happens.

– Helene Kröller-Müller’s epitaph.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!