5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born on 24 November 1864 in Albi, France. He wanted to be a doctor or a surgeon but due to illness became a painter. Art became sacred to him and embodied the basis of his existence. Here you will find out about how his disability affected the way he worked, the topics he chose, and the way he portrayed them.

To think I never would have painted if my legs had been just a little longer.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) was a child of Count Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec and his first cousin Countess Adele Tapie de Celeyran. The family was rich and lived on various properties in the south of France. In order to avoid division and reduction of property, the family members usually married between close blood relatives. This often led to health issues for their children. Henri suffered from a hereditary bone disease and after two accidents his legs didn’t grow anymore. It was during his reclining cures that he began to draw and paint, an activity which was at the time considered to be an enjoyable pastime.

Consequently, the surroundings of the family estates, the hunting, court milieu, horses with carriages, riders, dogs appeared in his first oil paintings. Horses that he loved but could not ride. Those paintings were already a reproduction of a spontaneous, rousing, and characteristic moment.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Count Alphonse de Toulouse Lautrec Driving a Four-Horse Hitch, 1881, The Petit Palais, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

Maybe these early paintings were his way to impress his father, who expected his son to be a rider, a hunter, and a soldier. However, he was convinced that if he wanted to achieve something, he had to be independent of his father’s expectations and from his overprotective mother. Although it was difficult for him, he started to lead a real bohemian life in Paris.

Photograph of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec by Paul Sescau, 1894. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

In the entertainment district of Montmartre, among curiosities and attractions, Lautrec was less noticeable among “his peers”. The trivial and brutal reality of Montmartre fascinated him. Especially the dance halls captivated him. He preferred to stay at the source of his pictorial subjects. He wanted to distract himself, to numb himself because he could or did not want to be alone, so as not to be confronted excessively with his extreme situation.

From the earliest oil studies, Lautrec tried to be authentic and not to beautify or embellish. His technique and a painterly free conception stood in contrast to the prevailing salon art. He portrayed places and situations that up until this point were not considered worthy of art. In his canvas, The Promenoir the Moulin Rouge, little Lautrec and his tall cousin cross the room in the background, while guests of the restaurant sit at a table in conversation. The guests are talking and having fun. At the same time, Lautrec passes by on the edge of the room as a stranger and voyeur. Lautrec loved to roam the bars with this relative as a funny couple. But he was not simply an observer, he spent his evenings sketching the dancers and guests.

Ugliness always and everywhere has its enchanting side; it is exciting to hit upon it where no one has ever noticed it before.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, , 1892-1895, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Museum’s website. Detail.

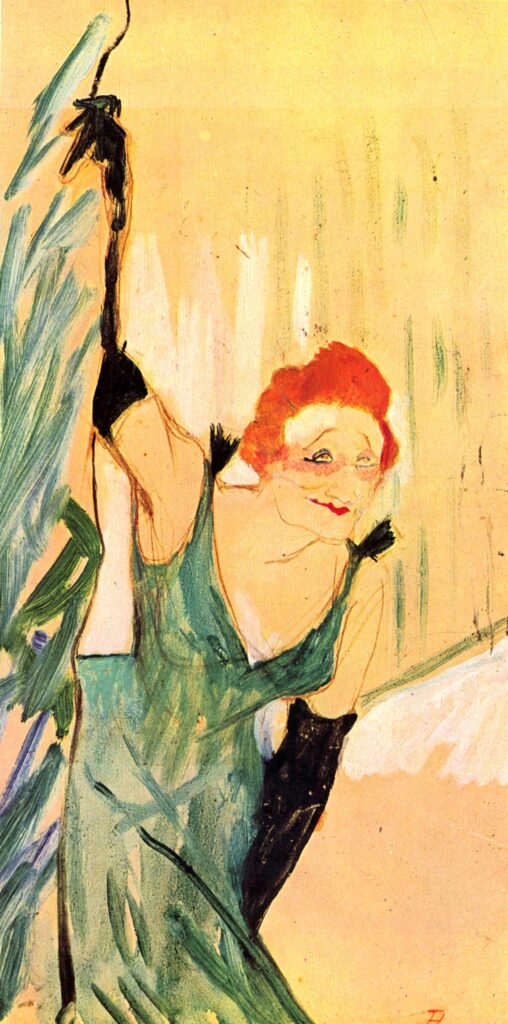

The cabaret singer and actress Yvette Guilbert was shocked at first by the way Lautrec saw and painted her. Later she seemed to have been convinced of his art. It was actually through his work that Guilbert became immortal. Lautrec conveyed the essentials and placed less emphasis on decorative accessories, as other Guilbert portraitists did. He drew her wearing long black gloves, which she wore during her performances. His portraits of Guilbert are memorable and the moments he depicted are highly original. One example is when she bows on stage after her performance in the picture below. His fast and accurate line simultaneously abstracts and clarifies the displayed object.

For heaven’s sake, don’t make me so atrociously ugly! Many people who come to visit haven’t been able to withhold terrible cries upon seeing it.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Yvette Guilbert Greets the Audience, 1894. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The subject of lesbian love seemed to intrigue Lautrec. Below we see two women dancing in a picture painted sensitively, almost intimately. Lautrec reflected the people and places that surrounded him, the life that he lived. Life was a big theater for him.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin-Rouges, Two Women Walzing, 1892. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

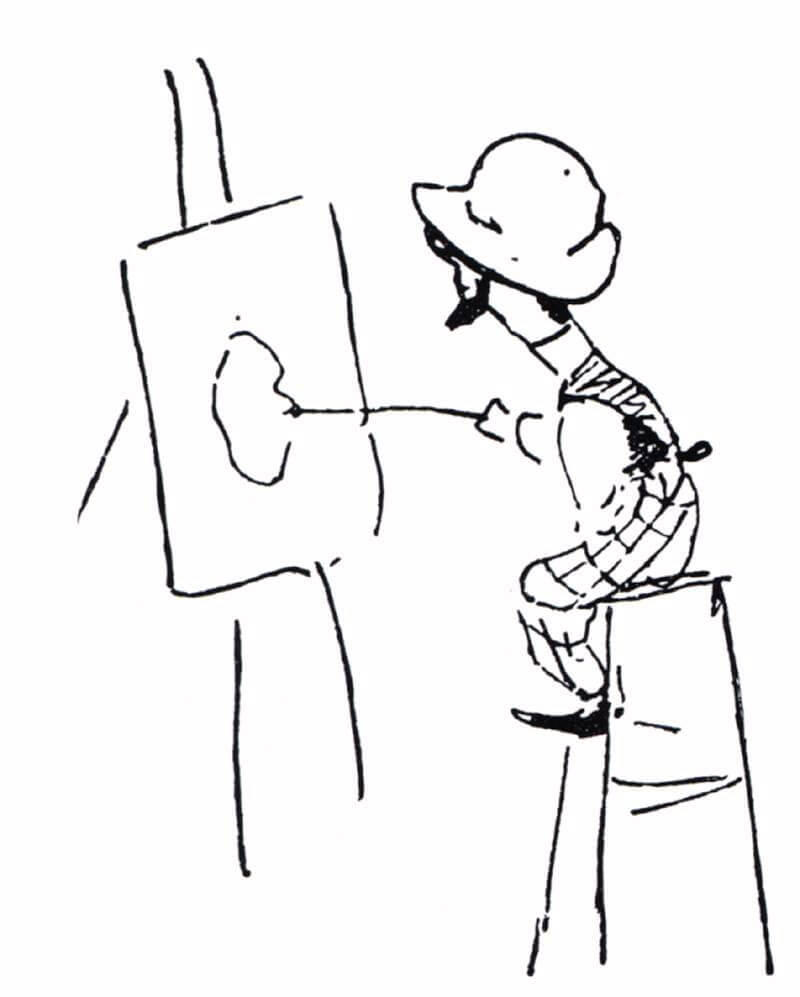

His face was quite distinctive, with a wide forehead, a big nose, and a receding chin. As a kind of self-protection, he developed an individual sense of self-irony:

Oh, how I should like to find a woman who has a lover uglier than I am!

In his numerous self-caricatures, he exaggerated all his weak points.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Self-Caricature Before the Easel, 1892. FineArtBilbo.

Although he was already physically weakened by his disability, the last few years in his life were like creeping self-destruction. His physical health problems, which resulted in emotional issues, made him a chronic alcoholic. He became arrogant, aggressive, and experienced hallucinations. He was able to paint almost to his last days though. During his lifetime, his work generated moral outrage and incomprehension. The themes in his images were detrimental to the “honor of the name” Toulouse-Lautrec. However, thanks to modern topics and his desire to represent the essential nature of his subject, he is recognized today as a major figure in late 19th century art.

Arnold, Matthias. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Das Theater des Lebens, Ingo F. Walther, Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1987.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!