Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

The greatest happiness can be found in the simple pleasures of daily life. Such simplicities could include the taste of fresh fruit, the smell of bold blooms, and the sight of crisp cloth. The stimulation of the senses can enrich lives as a meaningful interaction with the environment. Pausing and recognizing the ordinary beauty of life is a form of mediation. It is mindfulness. Henri Fantin-Latour achieves such soothing effects in his Still Life. This deliciously simple painting is now found in the Kröller-Müller Museum. However, first appearances can be deceiving because simplicity does not equate to naivety. Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

Henri Fantin-Latour painted Still Life in 1866. This was the era of both Realism and Impressionism. Gustave Courbet, James Whistler, and Édouard Manet dominated the art world and befriended Henri Fantin-Latour. Fantin-Latour and his Realist friends believed that paintings should not depict abstract and unrealistic images. Subjects should be painted naturally with a direct approach and not with theatricality. Fantin-Latour and other Realists rejected the exotic subjects, inflated emotions, and bold drama of Romanticism. They wanted to capture unidealized subjects with truth, accuracy, and objectivity. Henri Fantin-Latour expresses such beliefs in his Still Life.

Henri Fantin-Latour preferred to paint portraits and allegories but ironically achieved fame through his many still lifes. Fantin-Latour’s still lifes were commercially successful and extremely popular with art collectors. They were his livelihood and his main source of income. However, Fantin-Latour did not reduce his still lifes to mere routine work. He maintained his ideology and standards throughout his works including Still Life.

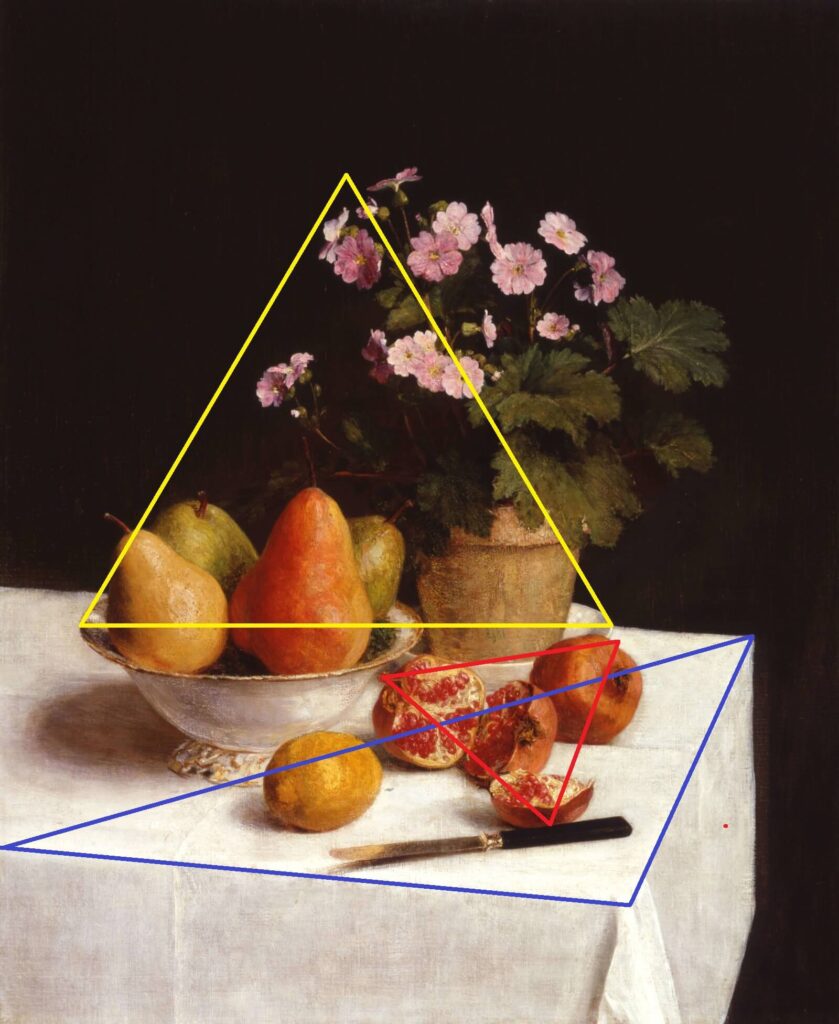

Henri Fantin-Latour believed that poetry and color were the basis of successful paintings. He believed his arrangements should be symphonies of colors, where warm colors contrast sharply against dark backgrounds. These poems of color create eye-catching and striking compositions. Still Life has pink primroses, red pomegranates, and yellow pears that juxtapose with the black backdrop. The white tablecloth and bowls add further disparity.

Henri Fantin-Latour also believed that his still lifes should not be a mere slavish pictorial copy of objects. There should be an element of human artifice to elevate these ordinary objects from nature to art. Fantin-Latour masterfully arranged his still lifes to play between geometric shapes and organic lines. Fantin-Latour infused his Still Life with three compositional triangles. Two of the triangles are equilateral and the third is right-angled. They add dynamic movement and prevent the composition of Still Life from falling into the stagnant inactivity of so many inferior still lifes.

Henri Fantin-Latour was a master of still life composition and color; talents unseen in France for several generations. Such mastery was last experienced under the Ancien Régime when Anne Vallayer-Coster, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin painted. Henri Fantin-Latour could easily be seen as the artistic inheritor of their combined legacy. At first glance, Henri Fantin-Latour’s Still Life appears simple and naive. However, with a discerning eye, it is revealed that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

Beckett, Wendy, and Patricia Wright. Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

Charles, Victoria, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Nature Morte (Primevères, Poires Et Grenades), 1866.” Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Accessed August 30, 2020.

“Still Life.” Google Arts & Culture. Accessed August 30, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!