Summary

The Louvre museum is not just the Mona Lisa, discover 10 hidden gems from the Louvre:

- Leonardo da Vinci’s You Didn’t Know

- A hidden gem of Romanticism: Liberty Leading the People

- Gruesome Rembrandt: Slaughtered Ox

- Michelangelo’s unrealized commissions: Slaves

- Louis XV’s gems: Marly Horses

- Egyptian Secrets: The outer coffin belonging to Tamutnefret

- Lamassu from the Palace of Sargon II in Dur-Sharrukin

- Decoration from the Palace of Darius I of Suse

- 10. Napoleon III’s Apartments

1. La Belle Ferronnière

There are more Leonardo da Vincis in the Louvre Museum than just Mona Lisa!

The first painting that is worth mentioning is Portrait of a Lady from the Court of Milan, also known as La Belle Ferronnière – literally, the beautiful wife of or daughter of an ironmonger. In fact, during the 18th century, the sitter was mistakenly thought to be a bourgeois and mistress of king Francis I of France. However, the real identity of the subject is still uncertain.

The painting was realized during the first period Leonardo spent in Milan and we can recognize in it his typical sfumato, an evident dynamism, and a wise use of light. Sfumato is a technique through which the subject has no definite outline and seems to fuse with the background. Then, Leonardo creates a very dynamic scene even if painting a portrait: the lady turns to her left, as if her attention is captured by someone. Finally, the light gently underlines the details of her face and richly decorated dress.

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of a Lady from the Court of Milan, also known as La Belle Ferronnière, 1490–1497, Louvre, Paris, France.

2. Virgin of the Rocks

Da Vinci’s second painting in the Louvre museum which has a very curious history is The Virgin of the Rocks. Also known as The Virgin, Child Jesus, Saint John the Baptist, and an Angel, it is one of two versions that exist. (The other can be found at the National Gallery, London, UK.)

This painting was commissioned by a confraternity for a chapel in Milan. The contract mentions a triptych, with angels, Virgin Mary in the center, and the Holy Father in the sky. It is not known why da Vinci changed the subject, but the confraternity refused to accept the finished artwork. In the meantime, for unclear reasons, the artist had begun the second version of his painting, a sort of “update”. There is still a debate around which is the first and which is the second version and about the real history behind these two mysterious artworks. Go and admire this masterpiece of the Louvre!

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin, Child Jesus, Saint John the Baptist, and an Angel, also known as The Virgin of the Rocks, 1483-1494, Louvre, Paris, France.

3. Liberty Leading the People

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was one of the giants of French painting of the 19th century. He was the main artist of the Romantic era of French art. Romanticism was a cultural movement in which the artist wanted to express every feeling of the human soul, to give a new value to emotions over reason, to exalt mysteries, dreams, fantastic visions and even exotic places, and the glorious past.

That is why some of Delacroix’s most famous masterpieces represent history, literature, or contemporary subjects, always full of feelings, power, and ideals. Probably one of the most beloved paintings in France, and in the whole world, is Liberty Leading the People. It is an allegorical representation of the events of July 27, 28, and 29, 1830. During that period, called the Restoration, new laws especially about freedom of the press were introduced, and the Parisian people rose up. Delacroix painted an ancient allegory of liberty, represented as a powerful and fearless woman, strictly connected to a contemporary subject, in a very Romantic way. This iconic artwork also includes a possible self-portrait of the artist: someone recognized him as the man on the right of Liberty, with a top hat and a carbine. An actual Louvre hidden gem!

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830, Louvre, Paris, France.

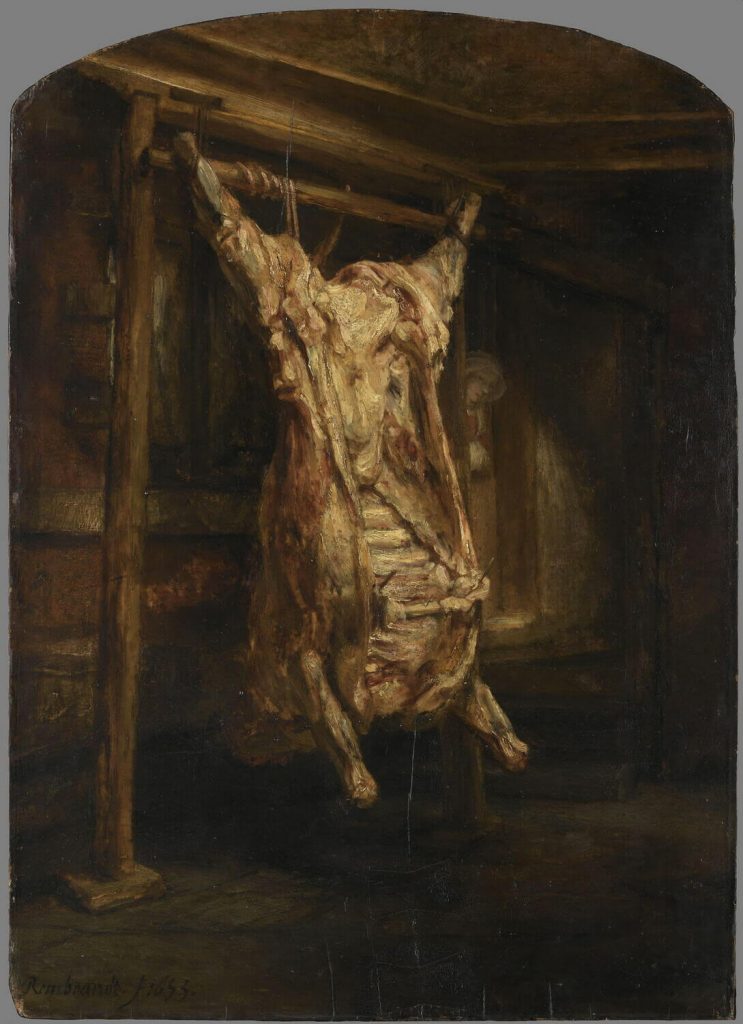

4. Slaughtered Ox

A masterpiece of Dutch art is Slaughtered Ox by Rembrandt van Rijn. A large chunk of meat hangs from a support, surrounded by a dark atmosphere. Someone skinned and removed the head of the carcass, no more organs can be seen within the animal. The artist painted with thick brushstrokes so as to make meat look real.

Like many other 17th-century Dutch artworks, this painting represents a realistic subject but hides a more profound meaning. However, this meaning is still unclear, or better it was never confirmed. Many different interpretations spread throughout the centuries. Someone saw in the painting the conclusion of the Prodigal Son parable, in which a son returns home after having lived a dissolute life and finally understanding the importance of good behavior. The father prepares a great dinner to welcome him back.

Then, another author thinks the ox represents the memento mori, a classical way to remember people they are temporary on earth; life should be lived in a good way always thinking of the Last Judgment. Moreover, other experts see in this painting a symbol of the crucifixion of Christ.

Vincent van Gogh gave a special interpretation, never proposed before: he thought it could be a representation of Saint Luke, patron of painters, whose symbol was an ox! Luke is also the patron saint of butchers, so the symbolism could perfectly correspond. Isn’t it a real Louvre gem?

Rembrandt van Rijn, Slaughtered Ox, 1655, Louvre, Paris, France.

5. Rebellious Slave and Dying Slave

In 1505, the Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to create his monumental grave, to be placed in St. Peter’s Basilica, in Rome. In Michelangelo’s original design, the grave would include about 40 statues. However, for unclear reasons, the Pope interrupted the commission. Only after his death in 1513 did Michelangelo work on the project again, but he completed it on a much-reduced scale. Some statues not included in the final version were already realized and gifted to people near to the artist. Among these are two young males that had been called Prisoners and later named Rebellious Slave and Dying Slave.

Someone said that Dying Slave represents the exact moment in which the soul leaves the body, while the Rebellious Slave and his struggle could represent the will to not bend to constrictions. Whatever the meaning Michelangelo intended to give, he almost infused life to these masterpieces. Don’t miss out on their beauty!

6. Marly Horses

The Marly Horses were commissioned in 1739 by King Louis XV from the artist Guillaume Coustou (1677–1746). The king had one of his residencies in Marly which he only went to with select people. The entrance of the palace already had two sculpted groups, but they had been then moved to Tuileries. So the King wanted some new, monumental masterpieces to decorate one of his favorite palaces.

The Marly Horses are two artworks realized in Carrara marble which represent rearing horses and their grooms. The models were personally chosen by the King in 1743 and the sculptures were completed and installed in 1745.

Later, in 1794, they were moved to Place de la Concorde. In 1984, fearing possible damage, copies were commissioned from a contemporary artist, while the originals were kept in the Louvre. Today they are the main attraction in a former courtyard in the Richelieu wing, which was since named “Court Marly”. Their incredible dynamics and beautifully finished details inspired many artists over centuries following their creation, for example Théodore Gericault. They are such a typical Louvre gem that will inspire you too!

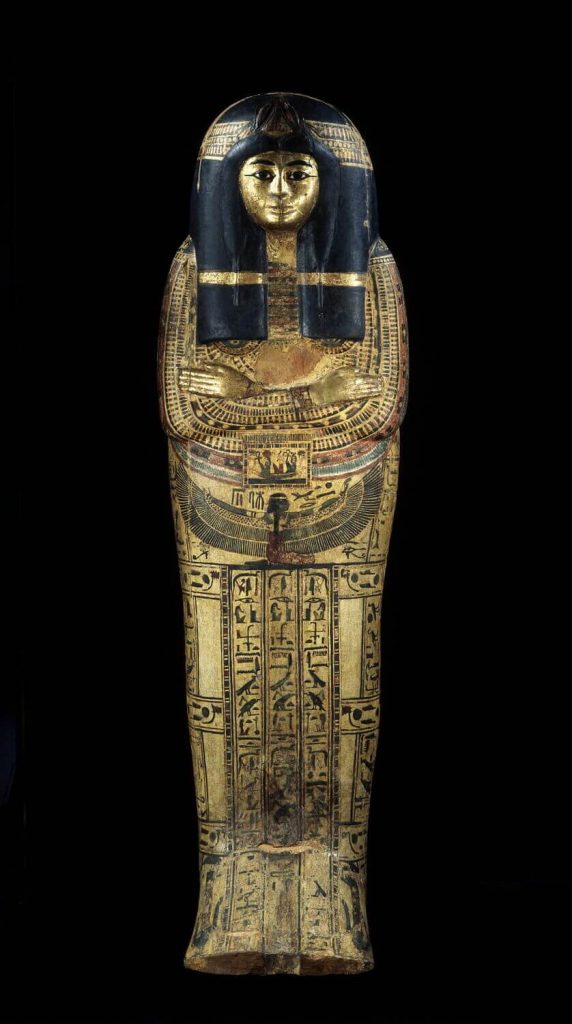

7. Outer Coffin Belonging to Tamutnefret

During the Ramesside period (1292–1075 BCE), a beautiful and perfectly conserved outer coffin was made in Egypt. It was found near a city that had probably been Thebes.

It is made of wood and fascinatingly decorated with colors and gold, with images of Egyptian gods such as Osiris, gods with sacred animal heads, Isis, Anubis, and of course with very complicated inscriptions in hieroglyph. As was the custom, these inscriptions are funerary sentences to accompany the dead through their journey to eternal life. This impressive artwork is 192 cm long and 59.5 cm wide, and you can admire it in the Department of Egyptian Antiquities!

Outer Coffin Belonging to Tamutnefret, 1295-1069 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France.

8. Lamassu

In the 8th century BCE, king Sargon ruled the Assyrian Empire. One day, he decided he wanted to have a new capital city. He chose a large site which would be named Dûr-Sharrukin, or “fortress of Sargon”, and the works began. However Sargon died, and his son and successor reestablished the capital city in Ninive, abandoning Dûr-Sharrukin.

The site was forgotten until 1843, when French archeologist, Paul-Émile Botta, found it. This is the origin of the oriental branch of archeology, which lead to the opening of the first Assyrian Museum of the world in 1847, at the Louvre.

Incredible low reliefs represent activities of the time such as archery and military processions, in order to glorify the King. Meanwhile other artworks probably played a magical role. On the doors, we can find huge winged bulls with human faces. They portray protective deities called Lamassu which were thus placed in strategic points in the King’s residence. Their double nature underlines their divinity and their goodness is enhanced by their smile.

Decorations of the Palace of King Sargon II in Dûr-Sharrukin, present-day Khorsabad, 8th century BCE, Louvre, Paris, France.

9. Decoration from the Palace of Darius I of Suse

During the 19th century, archeology saw a period of great development, in particular towards the East and Middle East. In 1884 and 1886, two French archeologists, Marcel et Jane Dieulafoy, studied a site which had been discovered some years before by the explorer William Kenneth Loftus: the Palace of Darius I of Suse. The laws of the time and colonialism permitted the displacement of entire sites, so this residence was moved and largely reconstructed in the Louvre Museum.

Darius (522–486 BCE) was a powerful king during the golden age of the Persian Empire, who had established Suse as his administrative city. The palace celebrates the magnificence of his family. Representative objects of this splendor now at the Louvre are a monumental capital with two bull heads and famous polychrome brick decorations. The latter were progressively reconstituted in the rooms of the Parisian museum, recreating the typical Persian iconography: lions, unicorns, griffins, archers. Everything celebrates the power and glory of the Empire, and as you walk throughout these rooms, you’ll be impressed by this Louvre gem too!

10. Napoleon III’s Apartments

Originally the Louvre was a palace, inhabited and visited by kings, ministers, and courtiers. A wing of the museum still remains as it was during the 19th century.

These are Napoleon III‘s apartments, a series of rooms and spaces full of rich decorations, elegant furniture, brocade armchairs, and extremely long tables. At the time, the rooms were for the prime minister during the Second Empire (1852–1870). They were later assigned to the Minister of Finance until 1989, at which point the Louvre became a museum and the apartments open to visitors.

Take some time to walk, surrounded by magnificence and feeling like a king or a queen!

Napoleon III’s apartments, detail of the theater room with a portrait of Empress Eugénie, 1858-1861, Louvre, Paris, France.