For centuries, the traditional art world asserted the importance of narrative in paintings. That is why the shift towards abstraction is one of the most important—and most radical—innovations of modern art. Interestingly, the question of who should get the credit for inventing abstract art does not have a clear answer. A few famous contenders dominated the conversation long before Hilma af Klint even entered it.

Kazimir Malevich claimed that his first abstract painting, Black Square, was created in 1913—making it the first. Black Square wasn’t exhibited until 1915 though, and there is no evidence that Malevich created other abstract works before then.

Similarly, Wassily Kandinsky retroactively claimed that his first abstract painting dated back to 1910. Art historians have since determined that, until at least 1913, Kandinsky’s work still contained subtle representational forms.

Piet Mondrian also explored abstraction during the 1910s. He explicitly wrote about his process of “abstraction” and created a series of works that, over the course of the decade, eventually rejected representation in favor of complete abstraction.

Meanwhile, Hilma af Klint began painting abstract compositions as early as 1906. Predating the aforementioned artists’ first forays into abstraction, her paintings feature nonrepresentational geometric and organic forms.

However, modern art’s major players were never aware of af Klint. So, the likes of Malevich, Kandinsky, and Mondrian could not have actually looked to her work for early examples of abstract art. Regardless, it is now clear that af Klint was among the very first—if not the very first—to start exploring its potential.

Who Was Hilma af Klint?

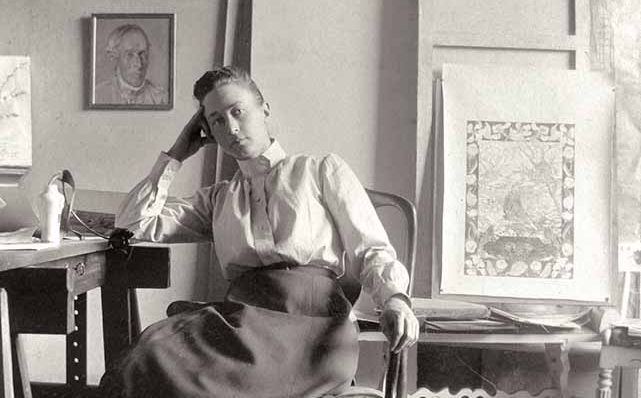

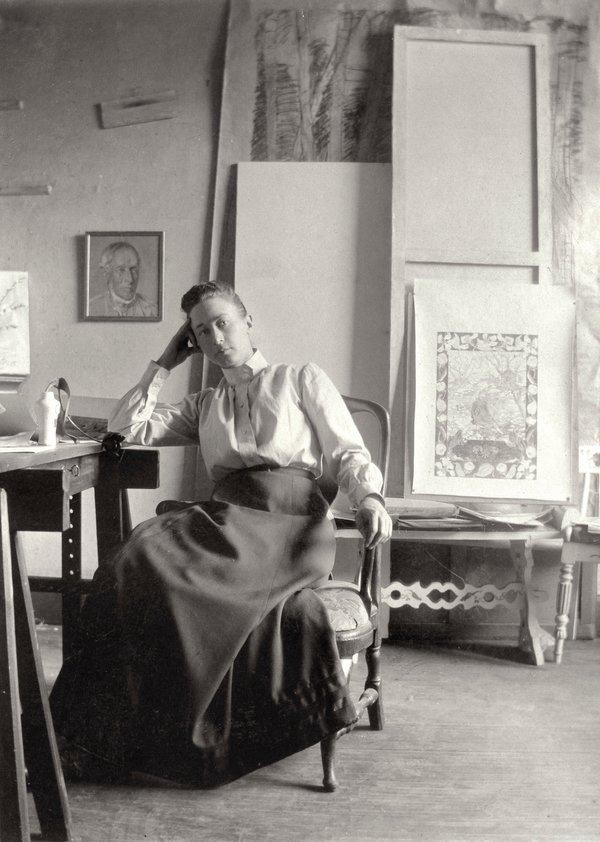

Born in 1862, Hilma af Klint enjoyed an idyllic childhood cultivating her artistic prowess, learning about mathematics and botany, and exploring the Swedish countryside.

When her family moved to Stockholm, af Klint began studying the visual arts in earnest. By age 20, she had been admitted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, where she graduated with honors in 1887.

It wasn’t long before af Klint found commercial success as an artist in Stockholm. She made portraits, exhibited various figurative paintings, and served as secretary of the Association of Swedish Women Artists.

Af Klint was also increasingly interested in Spiritualism—a movement predicated on the notion that a spiritual realm exists, and that people on Earth could interact with its inhabitants. Especially amongst artists, Spiritualism and other mystical movements became popular across Europe around the turn of the century. These ideologies offered a way for people to reinterpret their religious beliefs in the context of rapid scientific advancement.

As an art student, af Klint befriended four other women who also took an interest in mysticism. Calling themselves “The Five,” the women came together to meditate and make art at the behest of spirit guides. These experimental automatic drawing sessions catalyzed af Klint’s trajectory towards abstract art.

Although “The Five” eventually disbanded, af Klint continued exploring Spiritualist ideas and methods in her art. For several years, she focused entirely on Paintings for the Temple—a series of mystical paintings that she considered to be her life’s work.

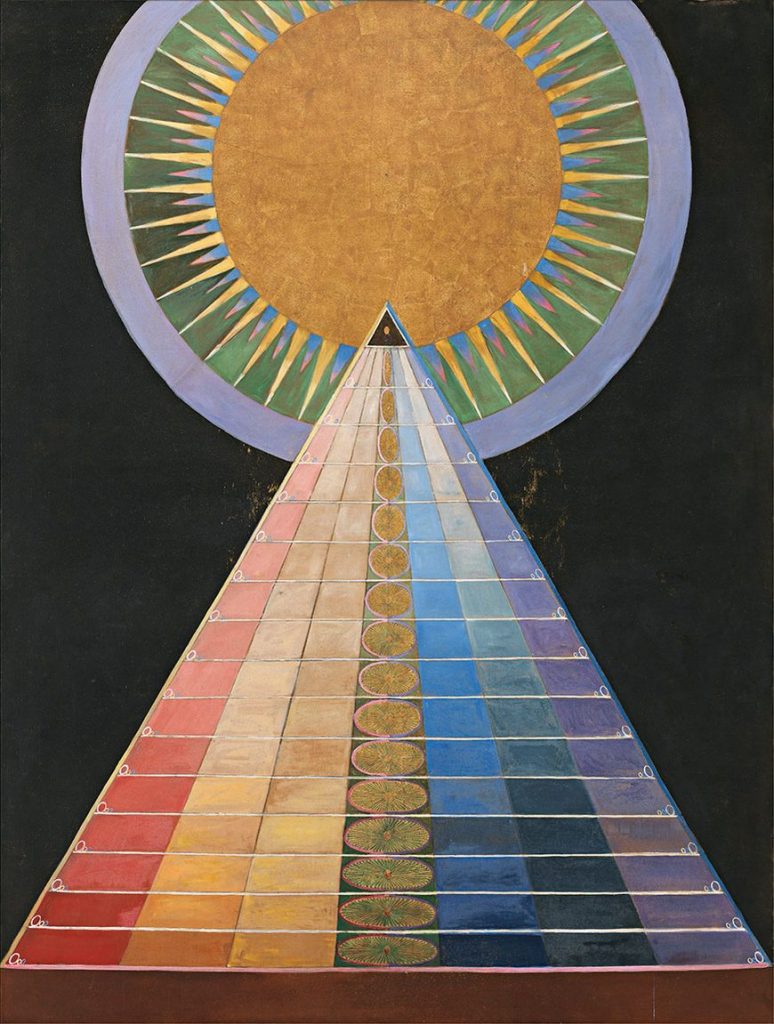

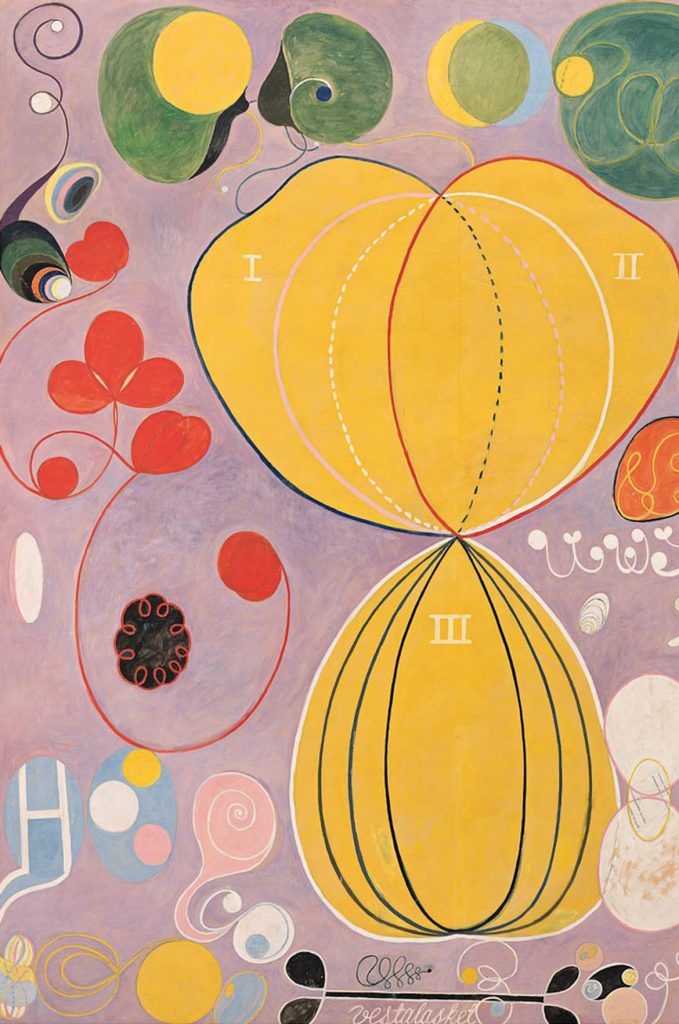

Paintings for the Temple

During one of her regular séances, a spirit guide told Hilma af Klint to create paintings for a “Temple.” Although she never understood where or exactly what this “Temple” was, she faithfully embarked on what became her most important body of work.

In 1906, at age 44—and 20 years into her career as an artist—af Klint painted her first abstract paintings as part of the Paintings for the Temple series. Along the way, af Klint believed a spiritual force was literally guiding her hand as she painted. Of the experience, she wrote:

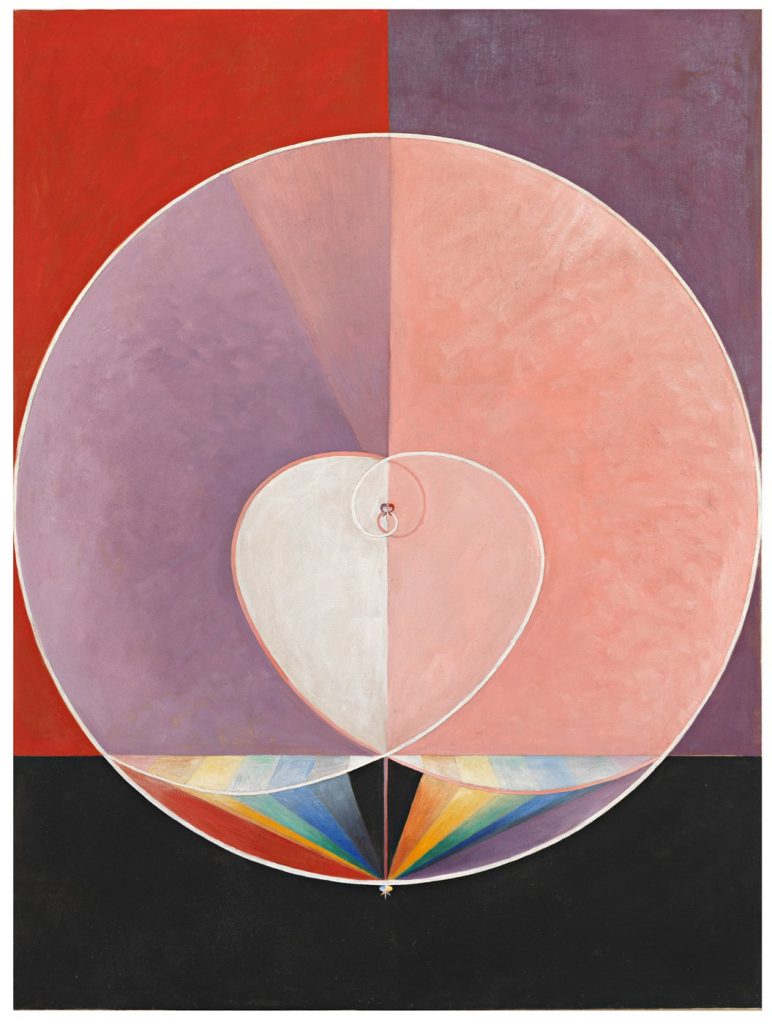

All 193 works in the Paintings for the Temple series—many of them totally abstract—were created between 1906 and 1915. While af Klint continued publicly exhibiting figurative paintings, Spiritualist themes and abstract forms increasingly dominated her private work.

Strangely, af Klint believed the world was not ready to see her abstract works, and that the “Temple” they were intended for could not yet exist. however, af Klint held out hope that future audiences would be receptive to her work. For these reasons, she kept her Paintings for the Temple secret. Her will even stipulated that these works remain unseen for 20 years after her death.

Unusual Legacy

Having exhibited just a small fraction of her work during her lifetime, Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at age 81. True to her wishes, her abstract paintings remained hidden.

Even after 20 years elapsed, af Klint’s descendants did not find an audience for her work until 1986. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985 was the first public exhibition to include af Klint’s abstract art. Her towering canvases—chock full of unusual color combinations, undulating organic forms, and subtle symbolism—did not go unnoticed.

Just like that, nearly a century, after she began painting abstract forms, af Klint’s mystical masterpieces, resonated with audiences in the way she envisioned. In 2019, a record-breaking solo exhibition of af Klint’s work at the Guggenheim Museum catapulted the artist further into the public eye.

Today, audiences can enjoy the uncannily forward-thinking aesthetic and captivating esoteric presence of Hilma af Klint’s abstract paintings in popular traveling exhibitions and prestigious permanent collections around the world.