The National Gallery in London: Where to Start?

Having lived in London for the past three years as an art lover, I have had more than my fair share of questions about where to “start” at the...

Sophie Pell 3 February 2025

27 February 2019 min Read

I avoided seeing the Hilma af Klint—Paintings for the Future exhibition in New York City for months because I did not like the abstract artwork the Guggenheim used to advertise it. I thought the shapes in the paintings were ordinary. And I did not feel the spirituality behind the artwork.

Then I decided to give Hilma af Klint a chance. I was intrigued by the notion that some of her paintings predated the official birth of the abstract art movement, raising many uncomfortable questions about the way art history is written. This was one of the hooks that the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum used to attract visitors.

I feel a sense of comfort and order when I think about the birth of abstract art. The official beginning of the movement was with an innocent black square that was apparently painted in 1910, even though the painting is dated 1913. The artist is Kazimir Malevich. And that black square, bold and direct, was the antithesis of the representational art that had preceded it.

Yet Hilma af Klint was painting her abstract shapes as far back as 1906. These shapes have more in common with Malevich and Mondrian than they do with Kandinsky. Af Klint was inspired by Theosophy just as many of the other abstract artists had been. Art influenced and inspired by Theosophy seeks to abandon the external world, resolving the conflicts within each person by creating an alternative to that external world. This alternative is one in which man and woman can serenely flourish as the duality between the opposing forces of the physical and the spiritual melt into a unified whole.

Two themes intertwine in my mind throughout this exhibition. The first is the influence of Theosophy on the formation and development of abstract art. The irony of this discovery is the realization that the presence of organized religion, which was so prevalent in the art world for centuries, was replaced not only by a more secular vision of the world but also by another form of religious expression. No matter how vigorously man wishes to dispose of religion as an updated version of mythology, an insatiable yearning for belief in a higher power and a world beyond our own still lingers strongly in many of us.

The second theme is the issue of how external forces having nothing whatsoever to do with the quality of an artist’s work have so much influence over how well-known an artist is. In the introduction to this exhibition, the Guggenheim clearly expresses why Hilma af Klint was not as famous as some of her contemporaries:

“Yet while many of her better-known contemporaries published manifestos and exhibited widely, af Klint kept her groundbreaking paintings largely private. She rarely exhibited them and, convinced the world was not yet ready to understand her work, stipulated that they not be shown for twenty years following her death. Ultimately, her abstractions remained all but unseen until 1986, eighty years after she began her monumental cycle, The Paintings for the Temple (1906-15).”

The first paintings that we see from af Klint are from her figurative period before she embraced abstraction. The skill evident in these paintings is the foundation for what follows. These paintings include Ketty, a small oil on canvas of a dog’s head in profile that is undated, and Cornflower, a landscape in watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper that was done in the 1890s. These quiet, intimate paintings have wonderful texture. The landscape even has a foreshadowing of some of the abstract qualities of the mature style of Mark Rothko.

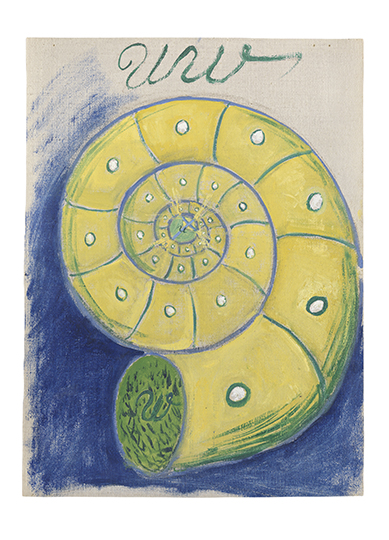

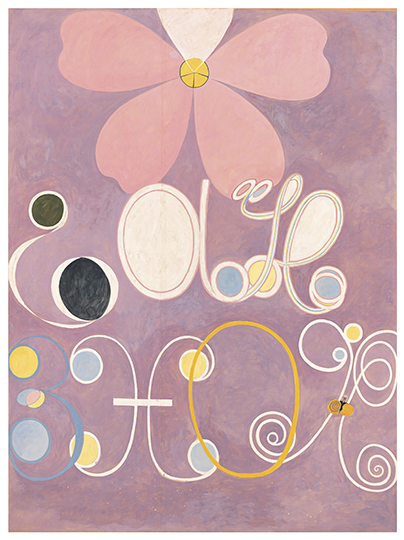

The first main room of the exhibition featured ten large paintings: Group IV, The Ten Largest. They were all tempura on paper, mounted on canvas, and were done in 1907. Symbolism is rampant in these paintings. Yellow represents man. Blue represents woman. Green is the combination of man and woman. Af Klint joined with four other women painters and had seances with them during this time. They were collectively known as The Five or De Fem. (It is tempting to believe that the name De Fem refers to the gender of its members or their crusading energy. Alas, the name refers only to their number.) Spirits spoke to them, providing guidance. Af Klint wrote voluminously. In her notebooks, she explained that the letter ‘W’ refers to matter, the letter ‘U’ refers to the spiritual world, spirals have symbolic meaning, as do ovals.

Af Klint believed that her contemporary world was not ready for the artwork she was making and was so passionate about. She had hope for the future generation to be ready, however, so she stipulated in her will that her paintings were not to be made available to the general public until twenty years after her death. She died in 1944 at the age of 82; it was not until 1986 that her works were exhibited for the first time.

Here we are, thirty years after this initial showing, and I stand before her paintings struggling in earnest to relate to them and to understand who the woman behind these paintings is. I can read about the symbolic meaning of her work, and I can see that she cares about what she’s painting very deeply, but I struggle to feel her passion beyond an intellectual grasping of small aspects of her work.

So in this first room, looking at blues and yellows and circles and joined circles, I can enjoy some aspects of some of these paintings—Number 3, for example. It has the feeling of childhood, and the way the yellow circles and the blue circles relate to one another, especially where they meet at one point and do not merge together, is somewhat poignant, but beyond this, my spiritual journey stops short.

When I look at a Mondrian or a Kandinsky, especially a Mondrian, I am able to feel what I think the artist is feeling, even if I am not able to explain the deeper meaning behind ‘Broadway Boogie Woogie’ and other works. The feeling comes first, the passion comes first, and then I become curious and want to know more.

Number 7 is one of the four paintings of adulthood. I am not sure what to read into this, but the yellow forms dominate the composition. The green shapes are there, lining the top of the paper, while blue is less represented, almost marginalized, in the lower left corner.

I must confess that I am enjoying these ten paintings as I review them on my iPhone a lot more than I did when I saw them in person. Ironically, the temple that af Klint envisioned has the same spiral quality as the Guggenheim Museum, making this museum the perfect home to display the artwork in this exhibition.

Some of the paintings move me a lot more than others. Some of the ‘Group I, Primordial Chaos’ are examples of this. A curved biomorphic form against a dark background is my favorite of this group. I enjoyed some of the Evolution paintings as well; the spiral is supposed to represent evolution. I also liked many of the more colorful paintings that have straight lines along with curves, such as The Dove Series. When af Klint puts small patches of color next to one another, her doing so reminds me of Paul Klée.

This exhibition will be on view until April 23, 2019. I recommend it, but with some trepidation.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!