Art history has its superstars: Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent van Gogh, Gustav Klimt. But with the recent $2.4 million, multiyear restoration of panels of one of the world’s most desirable masterpieces, the Ghent Altarpiece and the opening of the exhibition “Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution” in Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts, the beginning of this year (until COVID-19 occurred in Europe) belonged to the late-medieval master Jan van Eyck, and Ghent in Belgium was a place to be.

Van Eyck is a star now but he was highly appreciated also during his lifetime. Hired by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, Jan was not only a court painter but also Duke’s ambassador to faraway countries. He painted many religious commissions and portraits of Burgundian courtiers, local nobles, churchmen and merchants. These portraits are among his most breathtaking masterpieces. What makes his works even more valuable: only a small group of them survived with dates dating as far back as 1432. To be precise, only twenty-two works have been preserved. Thirteen of these are now on show at the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MSK) until April 30th, 2020. This is an exceptional chance to see much of his work gathered in one place. It a real once-in-a-lifetime experience.

I bet that van Eyck himself would love such exposure. Eventually, he was one of the first late medieval artists who signed his paintings. That made the work of art historians much easier as the attribution is always a tricky thing. It also is a statement of how the artist perceived himself. Van Eyck wasn’t just a regular craftsman – he was an intellectual, a creator proud of his work who used one of the latest innovation in art: the oil painting. His legend was so strong, that even after more than a century after his death, an Italian artist and historian Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, stated that the oil painting was created by no-one else, than van Eyck.

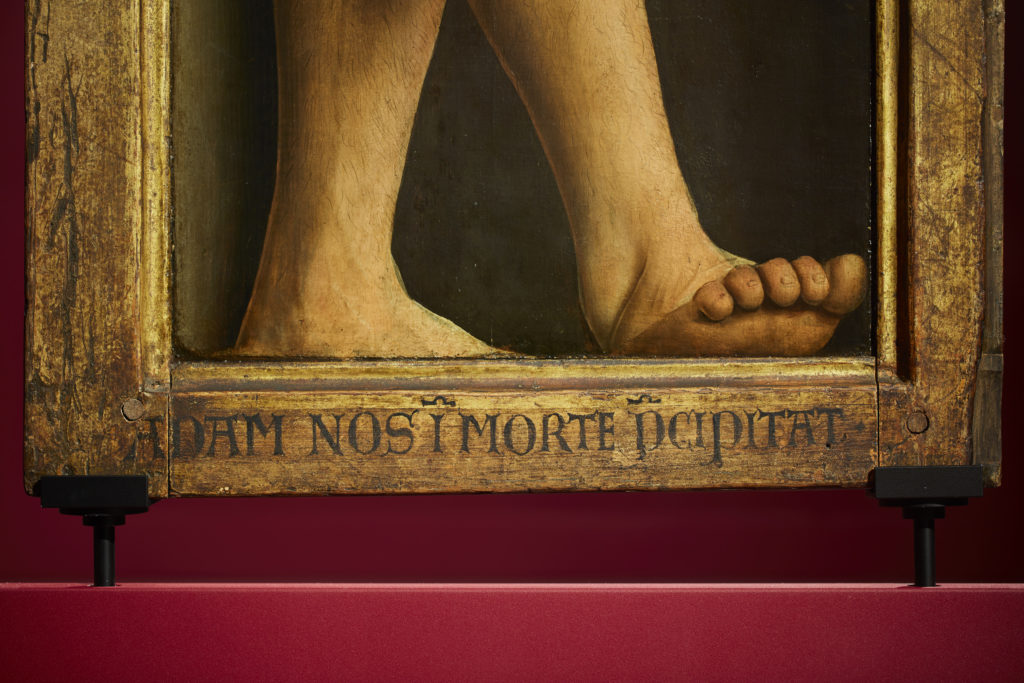

Oil paint was a tool to reach something bigger, a true optical revolution in painting. Van Eyck was a master of the impossible: impossible light effects; impossibly tangible fabrics (the velvets!); impossible stony 3D-like figures painted on a flat desk; impossible realism of a human body (look at Adam’s from the Ghent’s Altarpiece legs! Who else at the time could paint them so hairy?.; All that impossibility happened around 1430.

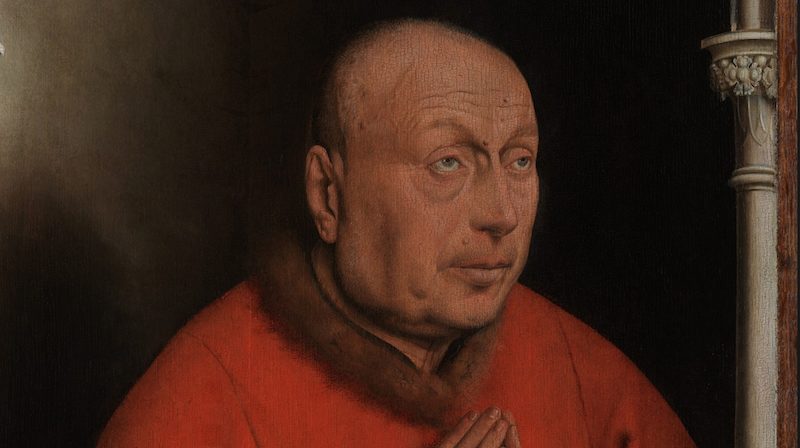

All these magical effects can be seen at the MSK’s exhibition. In the room devoted to his portraits we can see how gentle and sharp observer of a human nature he was. The highlight of this room is the wings of the Ghent Altarpiece with portraits of its donors, Joost Vijdt and his wife Lysbette Borluut are sweeping the viewer off his feet. Van Eyck brought a high degree of realism here – his study of the ailing couple in old age is unflinching and far from flattering. We see: watering eyes, wrinkled hands, warts, bald head and stubble streaked with gray. The folds of both figures’ skin are meticulously detailed, as are their protruding veins and fingernails. The couple died childless and the endowment to the church and the commissioning of such an unprecedentedly monumental altarpiece were intended for a number of reasons, primarily to secure a legacy and to simply be remembered. It seems that it was a very smart investment and the mission was fulfilled.

On the exhibition we can see another striking part of the Ghent Altarpiece – the panels with Adam and Eve. These nearly life-sized figures are the earliest treatment in art of the human nude combined with Early Netherlandish naturalism. Both figures’ eyes are downcast and they appear to have forlorn expressions. Their apparent sadness has led many art historians to wonder about van Eyck’s intention in this portrayal. Some have questioned if they are ashamed of their committal of original sin, or dismayed at the world they now look upon. I love that second interpretation – it would now be more actual than ever. Van Eyck omitted the usual motifs associated with the theme here; there is no serpent, tree or any trace of the garden of Eden normally found in contemporary paintings. It’s a pure humanism, without any symbolic cover-ups.

“Van Eyck’s powers of observation were astonishing. He looked at nature in a such a detailed way and he observed things no painter had ever observed before ” – says Matthias Depoorter, Assistant Curator at the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent and one of the exhibition’s curators. “Look at the tiny hairs on Adam’s legs, or at his portraits in general – in which we see signs of old age: warts, pimples, wrinkles. The sitters are not idealized at all, why would someone like to be portrayed like that?” – asks Mr. Depoorter.

By the way, this naturalism of Adam’s and Eve’s bodies was a reason why in the late eighteen century both panels were hidden away because of their alleged indecent nudity.

The exhibition is the one and only chance to see with our own eyes these smart, tiny tricks of van Eyck – Adam’s foot appears to protrude out of the niche and frame and into real space. Eve’s arm, shoulder and hip appear to extend beyond her architectural setting. These elements give the panel a three-dimensional aspect – and it’s easy to understand, why the curators of the exhibition entitled it “An Optical Revolution”.

Another possible title of the exhibition could be “A Scientific Revolution”. According to Mr. Depoorter, Van Eyck adopted an early scientific way of observing the world. “He was not a scientist, he wanted to paint God’s creation but in a more empirical, scientific way. In the Ghent Altarpiece he painted 70 different species of flowers and trees. It is a visual encyclopedia. Take a look at the rocks at Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata – they are painted so accurately that geologists can say in which geological period they were formed. No other painter before him adopted such approach”.

Saint Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent.

With this details and striking straightforwardness of van Eyck’s paintings we can understand more clearly why from 15th century we observe the ongoing obsession for the Ghent Altarpiece, also known as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. Its story was tumultuous from the beginning. It was ordered to be created by Hubert van Eyck, Jan’s brother, who died in the mid of the works. Then the job was taken by Jan, who created out of it one of the most admired paintings in the history of art. For the first 150 years it was placed in Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. Then, in 1566 the Protestant militants broke down the cathedral doors intending to burn the altarpiece, which they considered to be an example of Catholic idolatry and excess. But the work was hidden it in the cathedral tower, where it survived. Then, at the beginnings of 19th century it was taken as booty in the Napoleonic Wars and then returned to Ghent. Parts of it were stolen by a vicar at Saint Bavo and ended up, after several sales, in a Berlin museum. It took the Treaty of Versailles to finally reunite all the panels in their original home. In 1934 the left panel was stolen – and that theft has never been solved. Visitors to Saint Bavo Cathedral today will see a copy of the missing panel, painted during World War II. The copy is so good that many people think it might be the original, hidden in plain sight.

The final chapter of this violent story was written during World War II when on the orders of Hermann Goering the Altarpiece was stolen. It sounds like a scenario for another Indiana Jones movie, but Hitler and the Nazis were absolutely convinced that the Ghent Altarpiece was thought to be a sort of mystical treasure map showing the location of relics of Christ’s passion. It was super important to them. Luckily, at the end of the war the masterpiece wasn’t lost or destroyed (like for example, the famous Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man) but it was found in a salt mine in Austria by the brave Monuments Men, whose job was to hunt for looted art.

Now the Altarpiece can be seen again in the place where it belonged, in the Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. So if you look for it on the MSK exhibition you would be disappointed – only the panels with donors and Adam and Eve are there. To see everything you need to take a walk to Saint Bavo and wait to see it from a couple of meters, behind a glass wall in a small, very uncomfortable and dark place in the cathedral. I’m sorry to tell you that, but you can say goodbye to your dream to closely see the super weird humanoid face on the sacrificial lamb representing Christ.

The current place and the way the Altarpiece is exposed is quite debatable (although it is modern and safe) but the Cathedral later in 2020 will be opening a new visitor’s center devoted to the Altair, hopefully with better conditions to look more detailed at The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb.

It is much more comfortable to look at van Eyck’s masterpieces in the museum. The exhibition shows not only van Eyck’s works (The Annunciation from National Gallery of Art in Washington is like a huge OMG – have you ever seen such happy angel? But I must admit I would be equally happy if I had such rainbow wings) but also in total, 80 pieces of art: sculptures, drawings, tapestries and miniatures created at the Burgundian court and – for the comparison – in Italy, Spain and Germany at this time (so you can clearly decide who was better back then). It recreates an amazing world of the artistic and social context of van Eyck’s times.

The exhibition has been put together with major loans from collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Prado in Madrid, and the Vatican Museums. Spoiler alert: although London’s National Gallery agreed to loan of the mysterious Portrait of a Man (Léalsouvenir), the Arnolfini portrait and the probable Self-portrait from their collection stayed in London. Still, Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution is a true exhibition highlight of 2020 which proves that Flemish late Medieval art had only one king: Jan Van Eyck.

Couple of tips:

A tip no. 1: Unfortunately, you can’t take photos at the exhibition.

A tip no. 2: If you wouldn’t have enough of van Eyck you can easily catch a train to beautiful Bruges and see the Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele in Groeningemuseum. It’s breathtaking.

A tip no. 3: All works of Van Eyck are available to see online in high resolution at the Closer to Van Eyck website.

“Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution” runs February 1 through April 30 at the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, Belgium.

We would also like to thank Mr. Depoorter for agreeing to have a short call with us during the pandemic raging across the planet.