The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

26 June 2023 min Read

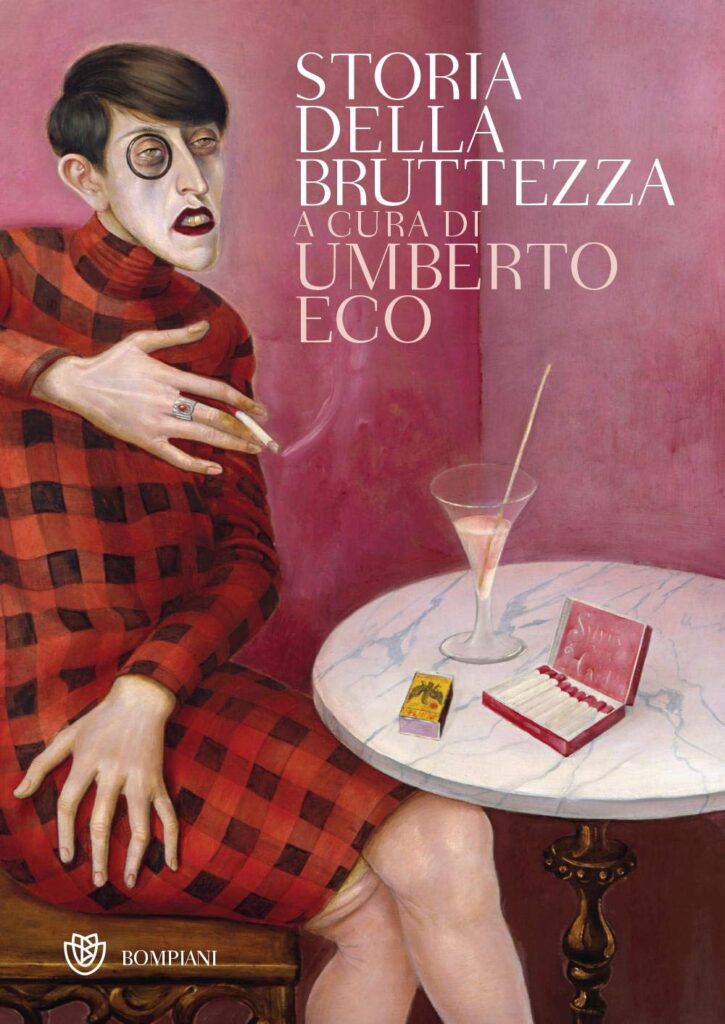

This book stood on one of my shelves for far too long. The compelling ugliness of its cover attracted me each time I longingly glanced at it. Now that I have finally read it, let me share with you my thoughts and feelings. On Ugliness is an impressive, yet disturbing anthology, bound by the words of the acclaimed award-winner, medievalist, and novelist Umberto Eco (1932-2016).

Book cover, On Ugliness by Umberto Eco, MacLehose Press, 2011, on the cover Otto Dix, Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia Von Harden, 1926, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, France.

On Ugliness begins with an insightful, engaging introduction. Each era had its own idea of what was beautiful – the same goes for what was ugly. There has always been a place for both in the figurative arts, while many philosophers and writers pondered mostly the idea of beauty. They did not consider its “counterpart” as much. Was ugliness then just the opposite of beauty?

Chimera of Arezzo, c. 400 BC, Etruscan bronze statue, National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy. Photo by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The first connection between what is horrid aesthetically and evil was only made in 1853, by the German philosopher Karl Rosenkranz. This is when ugliness detached from beauty a little and became more autonomous. In this sense, it acquired more value, a sort of richness of meaning, rather than a mere negation of symmetry, balance, and harmony.

Ogre, 16th century, Bomarzo Monsters Park, Bomarzo, Italy. Photo by Alessio Damato via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

In his incipit, Eco stipulates that there are two main types of ugly: a formal one (like a piece of art that one could find badly executed) and the ugly in itself (like… Poo). Ugliness, however, has been portrayed throughout the centuries by artists via every sort of media and register of images. So here comes a third type of ugly: the artistic representation of both formal and ugly in itself.

Francisco Goya, Witches Sabbath, 1797-1798, Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid, Spain.

[…] things we see with disgust we look at with pleasure instead the more accurately they are rendered, such as the images of the most repugnant beasts and corpses.

In Poetics, 1448b, 3rd century BC, Bompiani Milano (2000 Italian edition). Translated by the author.

Hans Baldung Grien, The Three Ages of Man and Death, 1540, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Detail.

Our insightful author also mentions Bonaventura from Bagnoregio, a 13th-century cardinal and philosopher who said that the devil could be beautiful, if well represented, in all his ugliness. To this statement, Eco counters that any regular 13th-century church-goer would probably have disagreed. Such a sight would most likely have been the cause of terror and anguish, rather than marvel at the artist’s visual achievement.

Giovanni Pisano, Hell, 1265-1269, from the Universal Judgment on the Cathedral’s pulpit, Siena, Italy.

Then the writer urges the reader to be mindful of such subjectivity and variability of perception of ugliness, as they embark on this journey through the deformed, swollen, and appalling faces of the Western World.

Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of Antonietta Gonzales, 1594-1595, Musée du Château de Blois, Blois, France.

As Eco says in his essay On Ugliness, the perception of the ugly, the uncanny, the oddity is subjective. Should this article entice you to read the book, you might find it not at all shocking, neither horrifying. Perhaps I am a bit delicate, but there are some scenes, whether painted, drawn, carved, or described on paper, that I found hard to digest.

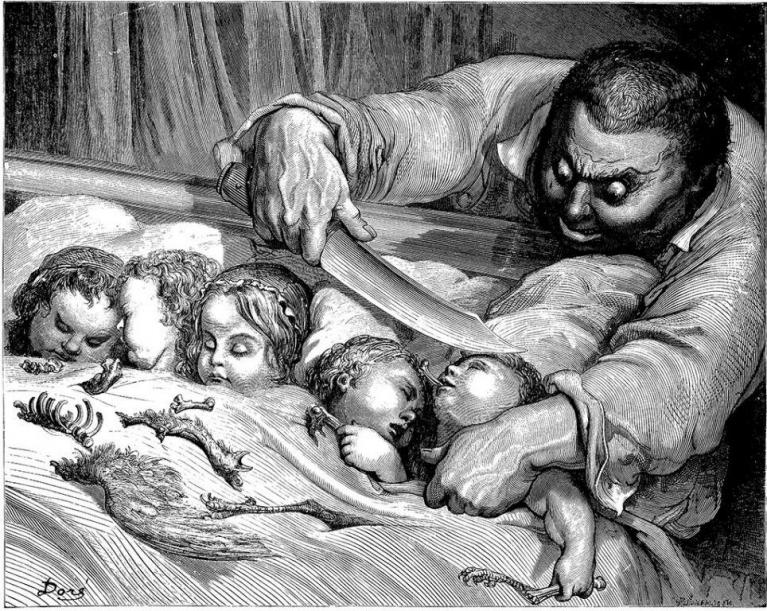

Gustave Doré, Engraving for Tom Thumb, 1862, from Le contes de Perrault by J. Hetzel, Libraire-Editeur.

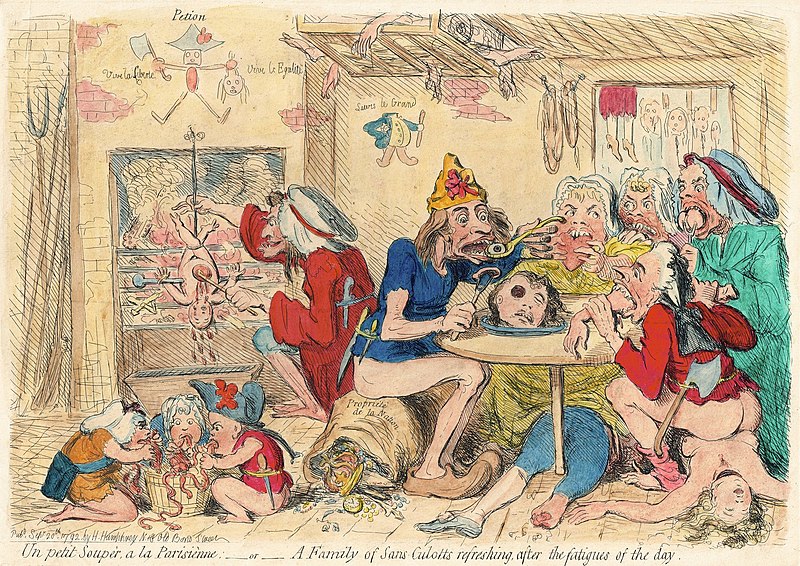

Starting from Chapter I, “Ugliness in the Classical World”, all the way to Chapter XV, “Ugliness Today”, the book provides the reader with precise timelines and thematic groupings: monsters and deformations, physiognomic fixations, dissections, infernal moats, tempting devils, bloody saints, the grotesque and the ridiculous, ugliness of gender, sick and miserable people, soulless industrial panoramas, racial satire, and more.

James Gillray, A family of sans-culotts refreshing, after the fatigues of the day, 1792, British Museum, London, UK.

Edvard Munch, Inheritance I, 1897-1899, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway.

Now, after having described the contents from a personal angle and showcased a selection of images (although all featured in Eco’s book), I feel I must strike a blow in favor of this splendidly revolting anthology. I thoroughly enjoyed On Ugliness’ narration and its extensive bibliography, matching each chapter’s theme and timeframe. Beauty’s infamous peer is interpreted far and wide. Ugliness’ history and the cultural shifts that caused it to acquire, lose, and then reclaim different characteristics in art and literature alike, are offered to the reader with clarity of purpose and objectivity.

[…] if violent movements get to set a being free from deep boredom, it’s because they can let in, due to who-knows-what obscure error, a horrible ugliness that satisfies.

The Dismal Game, Dedalo, 1974. Translated by the author.

Normally I don’t shy away from what is awkward and uncomfortable. It is a different story for what is disturbing and scary, I get all impressionable. Watching through my fingers is standard procedure when a horror movie is on and even so, I have nightmares for days. Hence, the reading of this anthology left me with a mixed bag of feelings.

Never mind my delicate stomach, this book delivers what it promises on its cover. Umberto Eco guides us on this disturbing journey as Virgil guided Dante. I won’t dare compare myself to the supreme medieval poet (although we are both very suggestible…). This author, however, makes a great Virgil, without any ifs, ands, or buts.

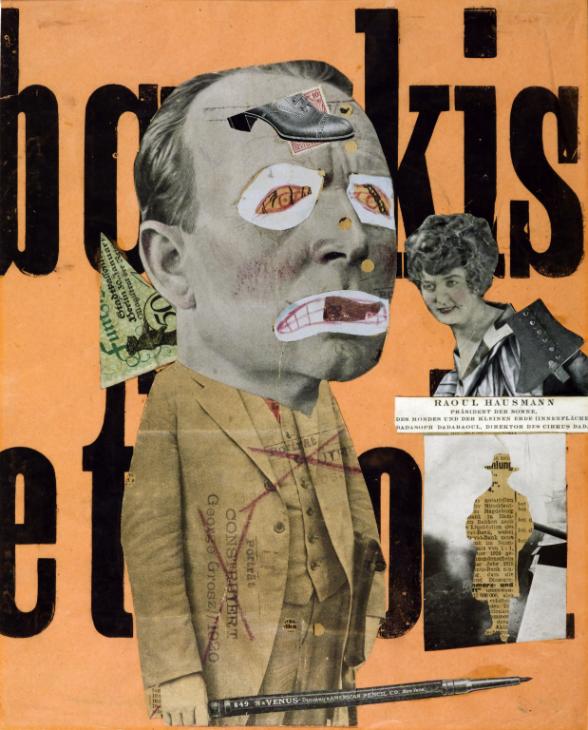

Raoul Hausmann, The Art Critic, 1919-1921, lithograph and printed paper on paper, Tate Gallery, London, UK.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!