The sudden expansion in trade, banking and the textile industry in the late 1200s brought an influx of labouring classes to the cities of Renaissance Italy. The Roman church, whose depictions of God were designed to control the congregation with the might and majesty of the Lord, was ill-equipped to deal with the vast numbers who set up home on the outskirts of cities This brought the travelling preacher to the fore. Preachers, such as St Francis of Assisi and St Dominic, brought a different way of viewing the life of Christ than the traditional view portrayed in the art works commissioned by the Church. Such men were ‘performers’, bringing a touch of drama to the stories they told the congregations.

To accommodate new towns of people, new churches were built and needed to be filled quickly with images of a Christ who would save their souls. The lengthy works were no longer appropriate, and so to speed up the process of decoration, the artists turned to fresco painting. A prime example of this is Giotto’s Lamentation of Christ from 1303-5.

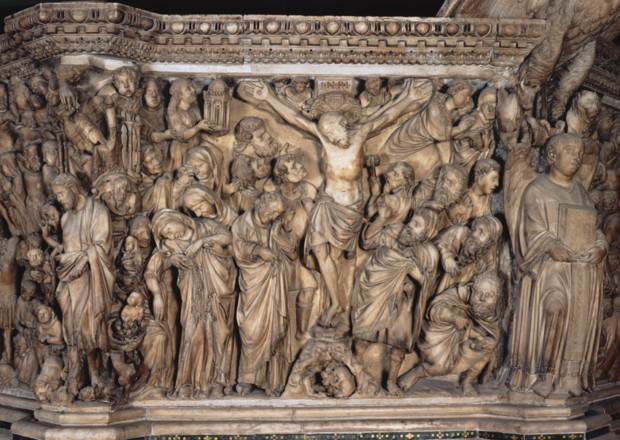

In this fresco in Padua, Giotto reveals the sorrow of the friends and family at this terrible event. Christ’s limp body is cradled by his mother; his hands and feet gently held by the other holy women. The other figures lean in to the scene and there is a distinct contrast between their controlled grief and the weeping angels above whose movements are agitated. This is how grief feels and looks according to St Francis. This is powerful iconography and we can also see this in sculpture. Giotto had been inspired by the relief sculpture panels by Niccolo and Giovanni Pisano of the Crucifixion:

The thin body, ribs showing, and face contorted with chaos all around: a powerful image and one that would resonate with the congregation.

In his book, ‘Renaissance’, Andrew Graham- Dixon commented that, “religion was one of the great driving forces behind Renaissance Art” and it is clear that this change was partly due to the influence of this new breed of preacher and the influx of artists ready and able to portray the holy story in a way that would resonate with the congregation.

At this point in the history of art, the technique of fresco painting was at its zenith. Two of the most famous frescoes from the Sistine Chapel painted by Michelangelo were completed towards the end of his time painting the chapel ceiling and are amongst the largest of the panels.

Here we see a very different depiction of the human body:

In The Creation of Adam, the composition is balanced in two halves to tell the story direct from Genesis, while The Temptation and Expulsion covers tells two parts of the story on the panel. The positioning of the creation is interesting, with God at a slightly higher position than Adam who languidly raises his hand to receive God’s power and might. The gazes of both are fixed on each other and there is a sense of authority and submission. This differs to Temptation and Expulsion as two distinct parts to the story are told here: The central Tree of Knowledge has Lucifer, as the serpent, tempting Eve while Adam grabs at the fruit. The second half shows the pair being forced out of Eden. While God and Adam gaze at each other in the Creation, in this panel no one appears to make eye contact.

Both paintings have elements of symmetry in the positioning that adds meaning as well as being pleasing on the eye. Adam and God are in a convex/concave shape. Similarly, Adam leans over Eve to reach the tree and Eve’s body curves towards Adam. Even during their expulsion, the same symmetry is in place.

From this, one can see that one of the most obvious features of both panels is the representation of the figures. The Renaissance artists were looking back to classical Greek and Roman representation of the human form and the importance of proportion. Adam and God are classically defined in both panels and Eve follows suit in the Expulsion.

The changes occurring in Art during this period were not restricted to Southern Europe. In the North, technical advances were making a difference to the works being produced, specifically in the promotion of oil paint.

Two artists, in particular, embraced the vibrancy oil-based paints could offer to bring new vigour to the holy story. Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432) uses twelve panels to tell the story and the attention to detail of clothing, landscapes, faces are all enhanced through the use of oil. This allowed the artist to look into the texts to bring details alive and therefore bring the word of God to the illiterate masses.

The use of tempura and fresco painting meant the speed at which the paint dries forced the artists to work on small sections at a time. With oils drying at a slower pace, artists were able to apply different techniques to the paint to give varied effects, including three dimensional modelling, thereby giving depth to the work.This idea is particularly striking with Roger van der Weyden’s moving Descent from the Cross.

This close composition is shot through with primary colour, the gold of the majesty of God, Mary’s Virgin blue, the red of Joseph of Arimathea’s robes. We can also see, with clarity, the grief etched onto their faces but what is most striking is the body of Christ himself. Every rib and sinew is defined. With oil paints being used to build up textures, we can see the flesh and the different materials within the composition with almost photographic realism. You only have to look closely at the tears falling from the actors to this scene to see the effectiveness of this technique.

The Renaissance was all about new art, new representation, new techniques, yet the oldest story known to man still resonated throughout the art world and gave it new challenges to develop.