The exhibition Van Gogh and Britain at the Tate Britain brings together over 50 works by Vincent van Gogh to reveal how he was inspired by Britain and how he in turn inspired British artists. The starting point here is Van Gogh’s stay in London between 1873 and 1876. Over the course of those three years, his fortune in the city varied and he tried his hand at various occupations. One that he had not embarked upon until 1880 was being an artist.

British Books

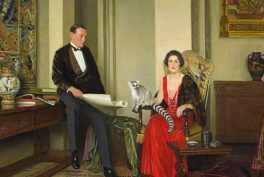

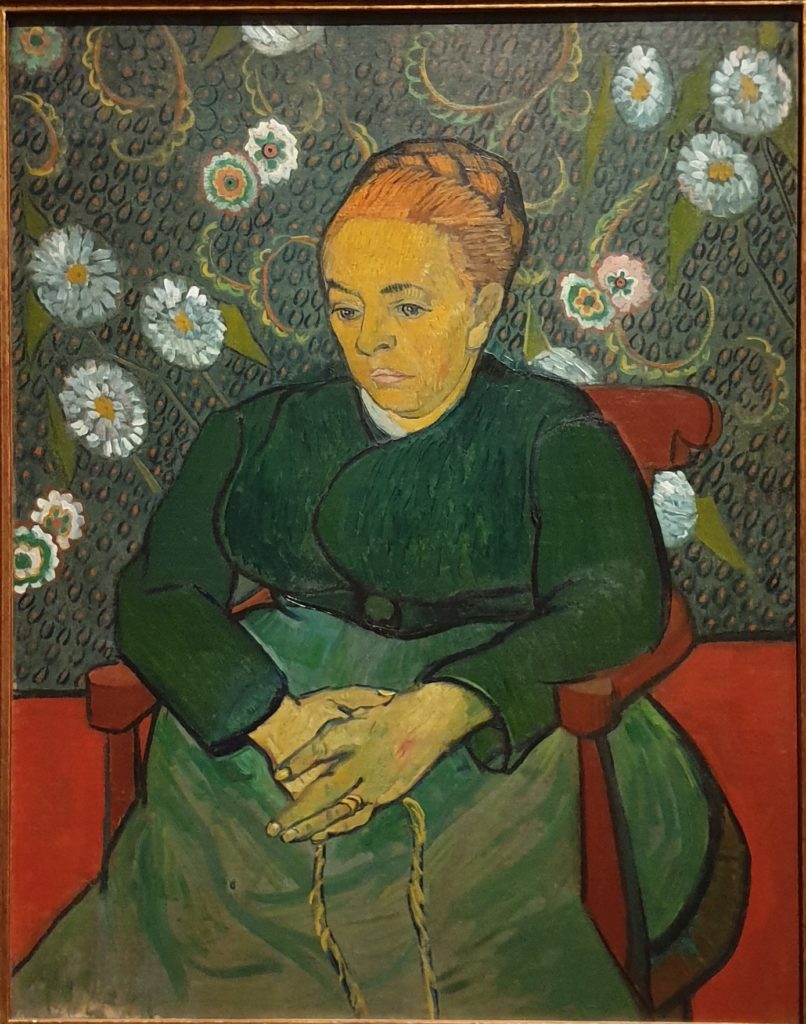

The exhibition starts in a sparse room with only The Arlésienne and a bookshelf. The point made here is that English was one of the four languages Van Gogh knew and he was a fan of English writers Charles Dickens and George Eliot. He mentions it in his letters and the final proof is provided by the books on the table in The Arlésienne. It is an interesting starting point if a bit skewed, as it does not account for his reading tastes in other languages he knew. This beginning, however, is certainly intriguing.

British Art

We are then introduced to a room that shows not only Van Gogh’s admiration for British painters like Constable and Millais, but also how he was inspired by them. This was when I started to struggle with the premise of this exhibition. As much as it is obvious that Van Gogh would visit galleries and experience and admire the art of British painters, he was not an artist himself yet. We are shown leafy landscapes of Constable and then autumn landscapes by Van Gogh, and yes, the subject matter is the same, but the point feels a bit forced.

Van Gogh had a difficult time in London. For the first two years, he worked at the offices of art dealer Goupil but did not enjoy the work and was not good at it, so there was only one conclusion to this situation – he was fired. After that, he tried his luck in teaching and preaching, with limited success, so he decided to leave London in December 1876, still looking for his place in life.

‘Black and Whites’

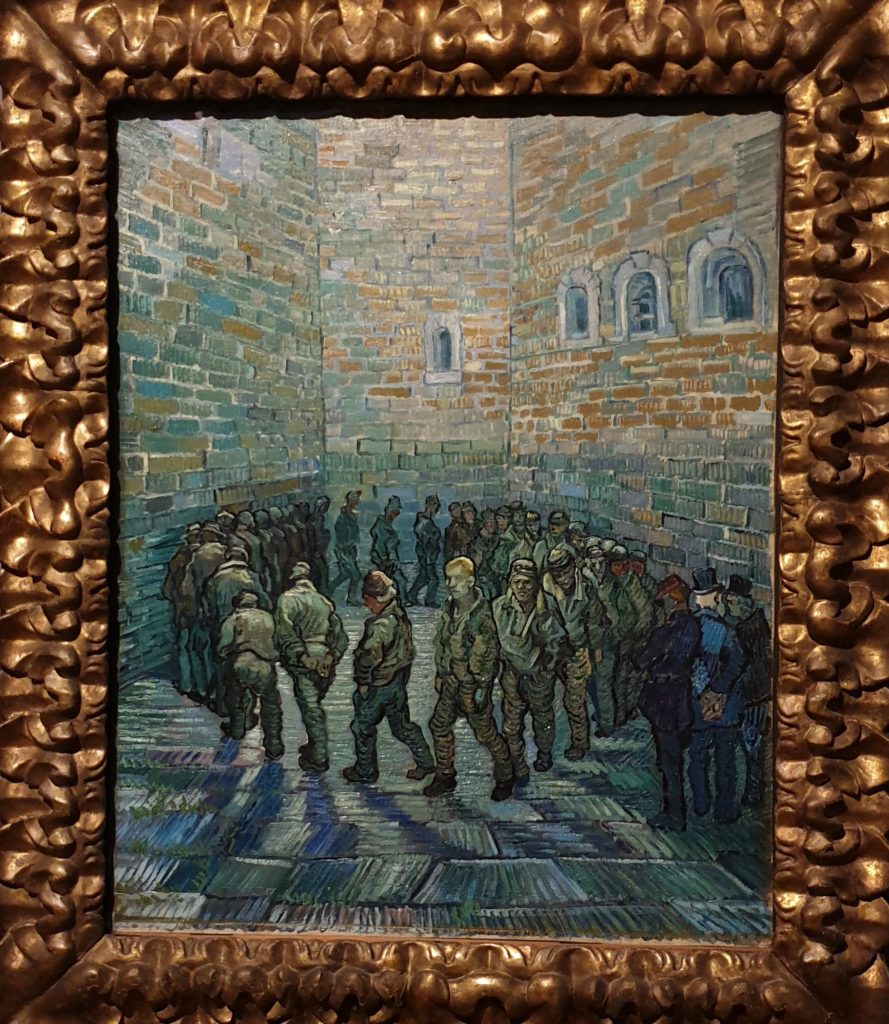

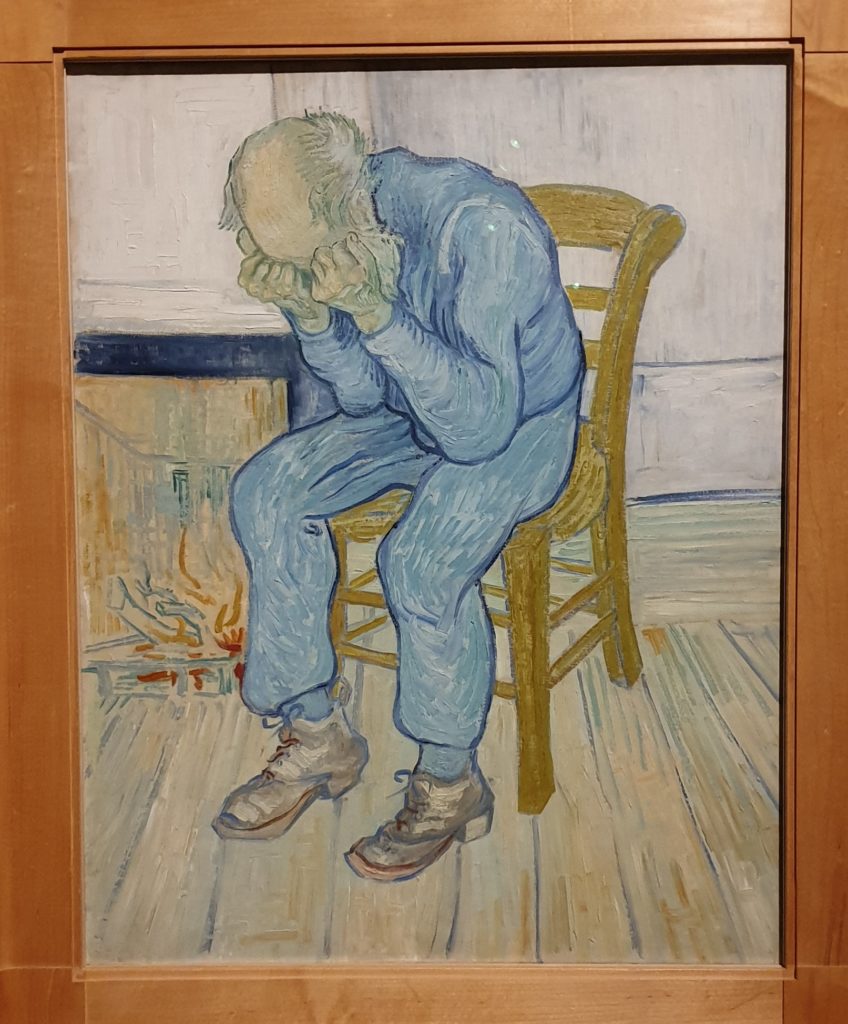

During his stay in London, Van Gogh encountered the growing trade in prints, known as ‘black and whites’. When he became an artist, he collected over 2,000 prints himself. Another aspect he became very aware of in London was the class and social issues and the hardship of the working class. Printmaking was one of the artforms that tackled these issues headfirst. As with many other artists, Van Gogh was inspired by the prints he owned, either in terms of the subject matter or composition. The Prison Courtyard is inspired by the print by Gustave Doré at the Newgate prison. Here again one can still argue that he was inspired by the foreigner’s perspective on Britain, not by the prison itself.

Van Gogh and the

Brits

The next two rooms are dedicated to the English artists van Gogh knew in France when he had become an artist and to the exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists that took place in London 20 years after his death and introduced him to the local audience. Here the connection seems to loosen up even more and becomes purely situational. Yet the several works by Van Gogh shown in those rooms shine a light of their own, surpassing everything else that is shown. If these two rooms prove a point, it is certainly that he was far ahead of the pack, rather than simply regurgitating ideas and inspirations.

‘A toi, Van Gogh!’

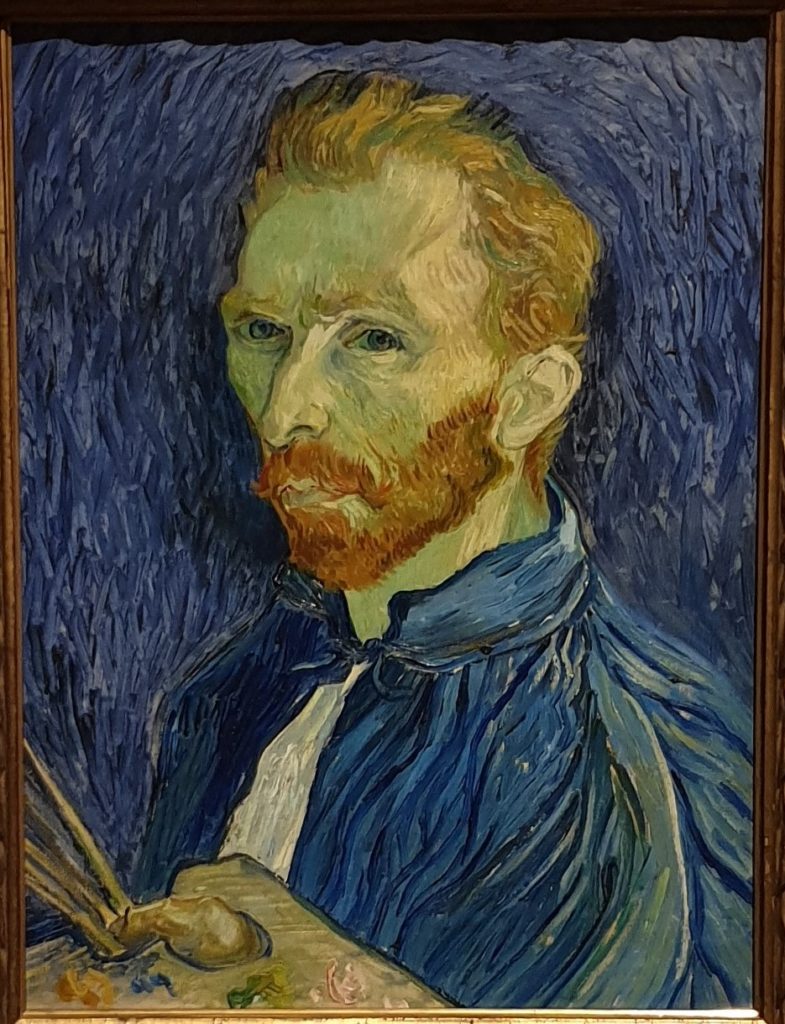

Apparently, Harold Gilman kept a print of a Van Gogh’s self-portrait on the wall of his studio. Before he began to paint, he would wave his brush towards the picture, declaring, ‘A toi, Van Gogh!’ (‘Cheers, Van Gogh!’). As charming as this story is, we’re treated to yet another room where the comparisons are as simple as they come, looking for direct influences of Van Gogh on British art: A tree for a tree and a field for a field. Interesting as it is, there’s bound to be a deeper influence at work, but the exhibition fails to explore it.

And so indeed we get a tree for a tree, but the culmination is the Sunflowers room, where we’re treated to the masterpiece as we enter and then surrounding it seem to be all the yellow flowers in the history of British painting. They are yellow, they are flowers, some of them may even be sunflowers, check, check, check, Van Gogh’s influence. It was certainly obvious to the group of small children in this room. It just makes one wonder why the grown-up audience is treated in such a patronizing way.

‘The Brilliant and Unhappy

Genius’

In the period between the two world wars, Van Gogh became an established modern master. In 1929, eighteen of Van Gogh’s artworks filled the final room of a large survey of Dutch art at the Royal Academy in London. His works were collected and he was known to the public. This, however, came with a very modern problem: His personal life became publicly known and this knowledge continues to impact our reception of his art. Tragic as it was, it was probably for the better that Van Gogh did not live to experience the ‘modern fame’ in all its overwhelming waves.

Continuous Inspiration

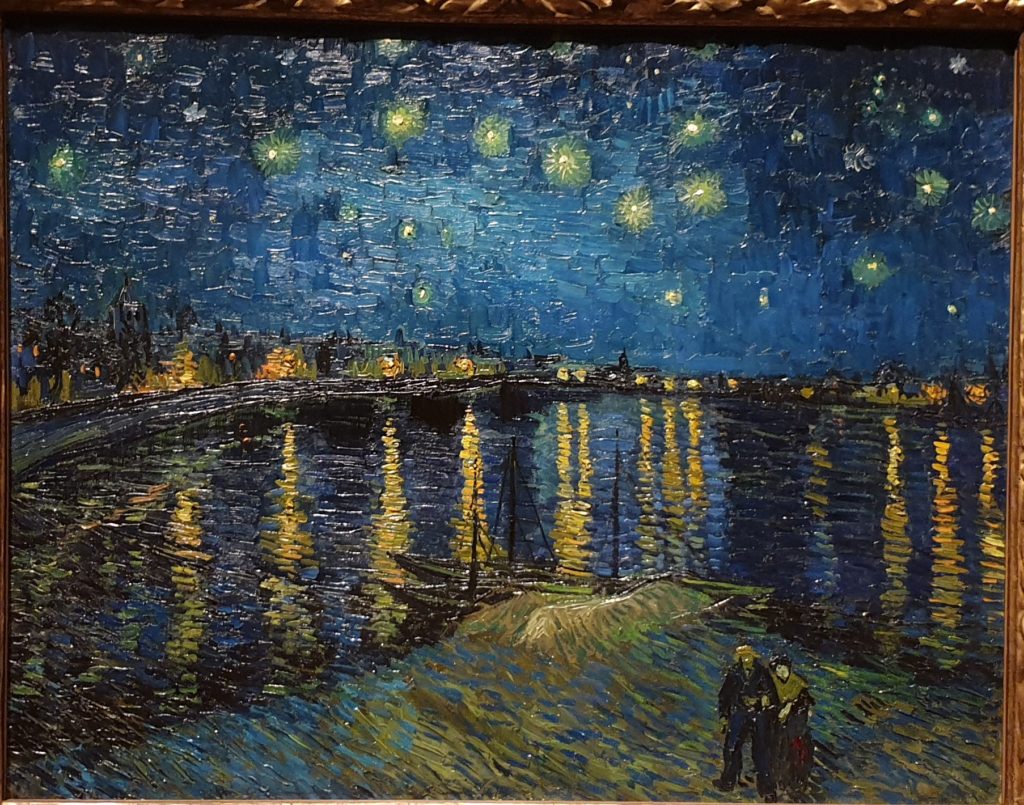

The last rooms are dedicated to Van Gogh’s influence on British art, including Francis Bacon’s Studies for Portraits of Van Gogh. There was potential for a better exhibition here, one that would start with Van Gogh and trace how he shocked and transformed British art: How his talent and vision continue to create ripples and inspire artists; how his art was embraced and rejected, how it filtered through new times and art forms and was both transformed and transformative. This would be a more interesting show, giving us a valid new perspective and broadening our horizons. Instead, we get a simple compare-and-contrast exercise. Still, with over 50 of Van Gogh’s works and highlights such as the Sunflowers, Shoes, Starry Night on the Rhône and L’Arlésienne, it is worth going, as they shine from the walls and defend themselves from being shoehorned into the exhibition thesis.

Tate Britain

27 March – 11 August 2019

Price: Adults £22,

Concession £20, Family child 12–18 years £5, Under 12s FREE (up to four per

family adult), 16–25? Join Tate Collective for £5 tickets