In this interview, Matsu discusses his creative process, his approach to combining disparate cultural elements, and the message he hopes to convey through his art. He also reflects on his diasporic identity and the challenges of navigating multiple cultural contexts.

Ania Kaczynska: Could you tell me a little bit more about Episodes Far From Home, your first solo show with Almine Rech in London?

Tomokazu Matsuyama: As a multidisciplinary artist used to creating large-scale sculptures, installations, and murals, the idea of creating a solo exhibition was not an easy one. Packaging myself, a Japanese artist, and this multitude of things that I create and connecting it to the dialogue with Almine Rech, who I have known for years, was a challenge.

What I wanted to showcase in London and in Europe is what I call visual dialect: references and images that bring us all together on an international scale, whether it be traditional culture, contemporary culture, popular culture, or consumer culture. I’m interested in trying to find the dots between them and create a type of chaos that’s more organic and less vocal. There is this notion of awkwardness in it, but also a notion of comfort.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, The Letter Half Awake, 2023 – Acrylic and mixed media on canvas – 269.2 x 194.1 cm, 106 x W76.4 in / © Tomokazu Matsuyama – Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech – Photo: Melissa Castro

Duarte.

In Episodes Far From Home you’re gonna first encounter a wallpaper. It is referencing a British wallpaper pattern called Tiffany’s Garden, a very traditional motif. I’ve taken that and redrawn it to make it more of a visually saturated, vibrant, artistic installation wallpaper. It’s welcoming the viewers from the outside and reminds them of something very local, even though it’s already translated.

The show features multiple canvases, which are shaped canvases, referring to traditional Japanese and Chinese paintings and Japanese folding panels. However, in some images, the figures are placed in interior settings. Those are referencing something completely different: they are inspired by Western magazines, such as Elle Decor or Architectural Digest.

In my work, consumer culture and popular culture contrast with Zen meditative and Asian visual language.

But it is not to talk about what’s East and what’s West, it’s more about what it means to live in this day and age where information is abundant. My interests lie in finding a connection between then and now, the past and the present, through that contrast.

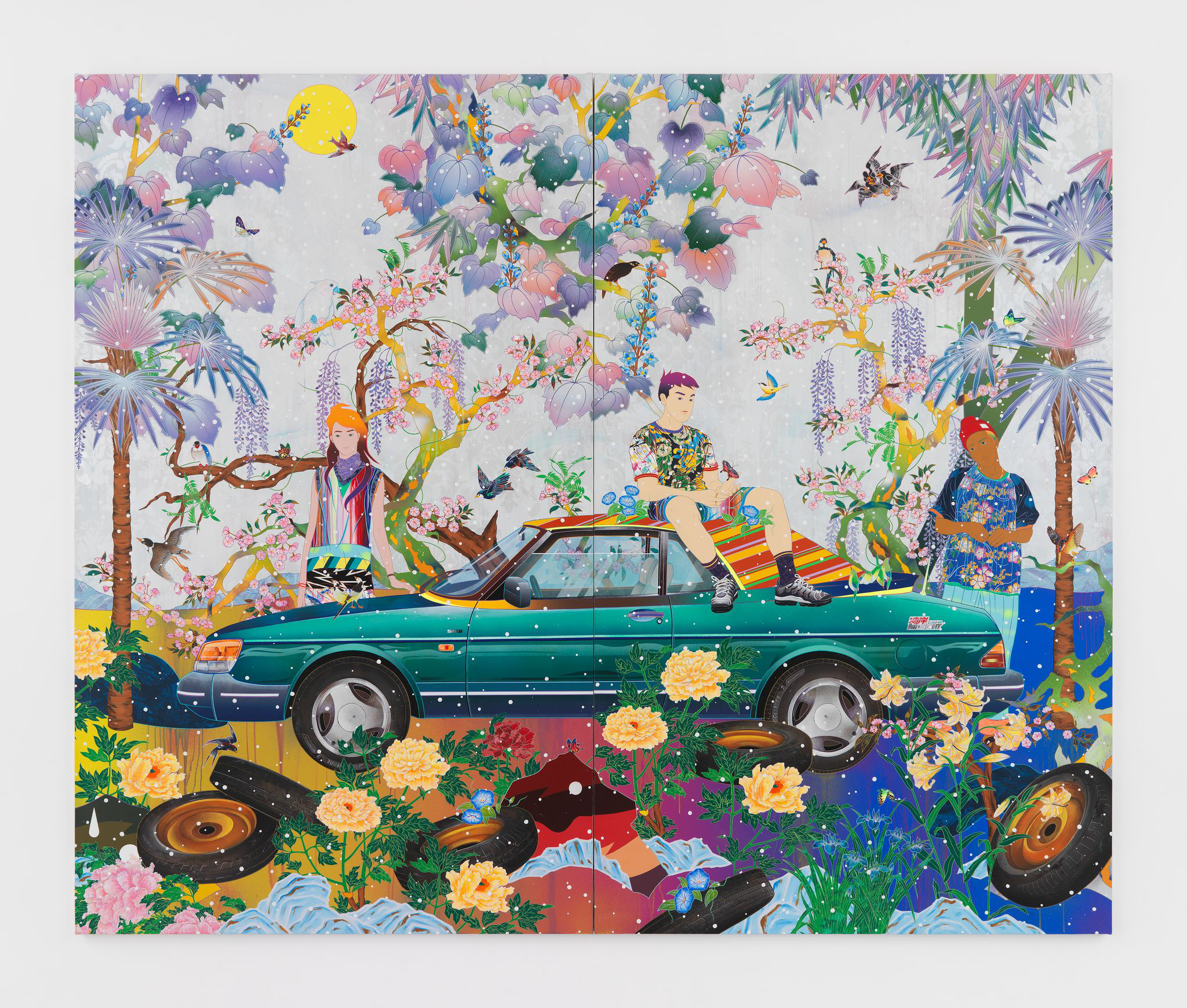

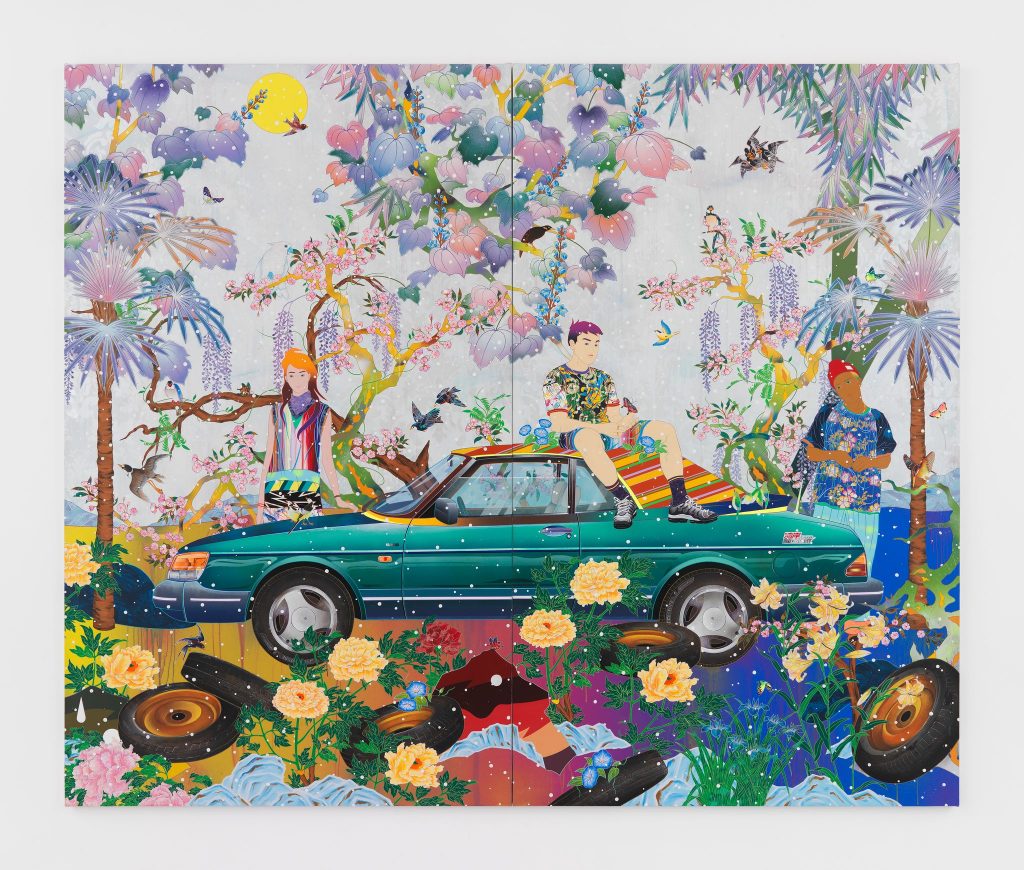

Tomokazu Matsuyama, Winter Song Solitudes, 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas © Tomokazu Matsuyama. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte.

AK: Your artistic practice is often described as cross-cultural, combining both Eastern and Western influences, such as ukiyo-e prints or European Renaissance paintings, and melding their aesthetic principles together. This results in a style that resists any categorization. What does this collision of cultures mean to you?

TM: For me, it’s not just about the clash of cultures, but more about what we can relate to as individuals. I live in America and have also spent time in London, which is a very multicultural city.

America, particularly New York, is a melting pot of cultures and languages, with more than a hundred religions being practiced. This results in a diverse range of values that we all live with and independence being celebrated and encouraged.

However, as a New Yorker, I question what individualism really means. Is it just about being loud and proud about our backgrounds and identities, both positive and negative? I find it challenging to connect with people from different backgrounds because everyone is so unique and there is no norm.

Although the art world is still dominated by white men, at the same time there are many voices and identities being amplified to be accepted. This is where I bring in my reality and try to create something visually elegant and artistic.

AK: And where did this interest to engage with art historical themes emerge in your practice?

TM: My creative motivation is to include art history references, such as Picasso or Japanese paintings, along with consumer and popular culture references, like bags of potato chips and current fashion attire.

I’m interested in how visual information becomes validated as historical and why certain pieces are deemed important and displayed in museums.

I find it subjective and wonder what makes art historical or contextual. As an Asian artist, I don’t try to adapt to what’s considered art history but instead try to find my own connections between different pieces, even if they seem to clash, such as corporate logos and historical paintings. I see no difference in the information we consume in daily life and the pieces displayed in museums.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, Winter Song Solitudes, 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas © Tomokazu Matsuyama. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo by Melissa Castro Duarte.

AK: You mentioned popular culture, which has been a recurring theme in arts for a while now. Do you see yourself criticizing it, or do you want it to be deliberately ambiguous?

TM: I don’t like to criticize, but I am aware of what’s critical. Perhaps it’s because of my Asian background and the way I was taught about contemporary art, which built upon American post-war movements and -isms. As the multiculturalism era began, we started to focus on our own identity and history, which unfortunately often spotlighted negativity. Being Asian, I never felt part of Western history; now, anti-Asian hate is ceasing to be invisible, yet I’m hesitant to bring that into my art.

Traditional Asian art often referenced hope and luck, with sculptures of Buddha meant to bring happiness and long life. Asian art was never a propaganda tool but rather a utility object; it was used to depict nature and the four seasons, which became a representation of life, death, reincarnation, and Zen. The West, on the other hand, built history on portrait painting, funded by the aristocracy to idealize themselves and their lifestyle, with Napoleon being a prime example. I appreciate both traditions and follow the historical trends of the West while also incorporating the emotional elements of nature and life that are prominent in Asian art.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, No Skin Echo Boomed, 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas © Tomokazu Matsuyama. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte.

AK: Evan Moffitt has described the textiles and the use of wallpapers in your work as “camouflage.” Would you say that it is a response to the state of the global art world today in the context of cultural sampling on an international scale?

TM: The world we live in is all about ownership. The battle for who owns what has been fought between identities, politics, countries, and nations. I became interested in patterns and textile designs because they are not linguistic. You can instantly feel a culture when you see something like a phoenix or a dragon. It’s a no-brainer that you associate them with China, and it’s just a fact. Similarly, when you see dark navy and flowers, you can connect them to traditional Japanese culture. However, the earth is a sphere, and as I researched more, I discovered similarities between different cultures. The Silk Road is an excellent example. It started in Egypt, went to China, and then spread across the world. Every culture claims that the information that stayed with them for a few decades or centuries is theirs.

For instance, Japan had a Gingham check, and Scotland is famous for its checkered patterns. In America, it’s associated with a picnic blanket. Each culture has its own overestimation and pride, but interestingly, they imitate each other’s designs too. This realization was intriguing to me, and I started incorporating different patterns, such as William Morris’ or Japanese patterns, intentionally in my paintings. That allowed me to overlay different identities and cultures in one picture as a way to talk about globalism. What is revealed is neither American, English, nor Asian; it’s utopian.

Being an Asian artist in New York, I had to find my own voice and a way to make it reach others. It was almost like camouflaging myself, and my motivation to thrive relates to this subjectively.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, This Is What It Feels Like, 2023, FRP, wood, steel, epoxy, polyurethane, acrylic, plastic and gold leaf © Tomokazu Matsuyama. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte.

AK: The gallery space in Episodes Far From Home involves paintings on flat surfaces, but also three-dimensional sculptures. How did you navigate between them in the process of their creation?

TM: Many Japanese artists have created sculptures based on their paintings, but I don’t follow that trend. I was inspired by artists who create sculptures that are conceptually similar to their paintings but still very different, like Lichtenstein, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons.

Tomokazu Matsuyama, Mother Other, 2023, FRP, wood, steel, epoxy, polyurethane, and acrylic © Tomokazu Matsuyama. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte.

When I create outdoor sculptures, my materials are limited, so I’ve been using a lot of stainless steel and mirrored finishes. Although my paintings are known for their vibrant colors, I’ve received feedback that my sculptures lack color. But with my new indoor sculptures, I’ve brought in visual elements from traditional Japanese images and icons, adapting them with gold leaf and other craftsmanship skills that have been used for over a thousand years. For example, the sitting figure in the center of the gallery is adorned with Gothic, Victorian, and Rococo architectural patterns, which are then applied to form a figure with a duality of different decorative arts. I wanted to create something massive for this exhibition, drawing on the design movements of Paris and London, such as Art Deco and Art Nouveau, which were influenced by Japanese culture.

By going overly decorative, I hoped to challenge the notion that decorative art lacks concept, and I think people responded positively to the intentional translation of traditional formats into contemporary art.