Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

13 January 2022 min Read

No phenomenon pertaining to human existence is as infallible and foundational as death. Expectedly, an occurrence that has this kind of defining nature could never be overshadowed by any other intriguing subject for artistic interpretation. But to interpret and convey such subject requires both physical and intellectual vigor; for one may easily find herself/himself in a despondent state in face of death and its repercussions within an environment as with death, comes mourning and gloom. Visual artist, Ioanna Sakellaraki, masterfully achieves this in an inimitable and candor demeanor through her project, The Truth is in the Soil.

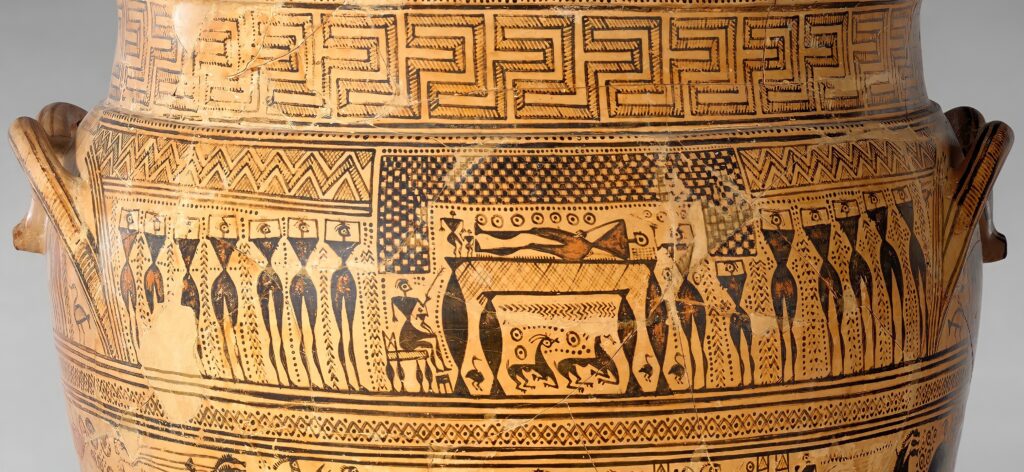

Damon Painter, Achilles mourned by Thetis and the Nereids, Black-Figure Hydria, c. 560-550 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Photographed by Herve Lewandowski. Detail. Artstor.

Πότε γὰρ ἐν ἡμῖν αὐτοῖς οὐκ ἔστιν ὁ θάνατος;

For when is death not within our selves?

Plutarch, Consol. ad Apoll. 10, p. 106.

Before directly delving into Sakellaraki’s project, we first ought to briefly observe the roots of the mourning tradition in Greece. Both the source material and archaeological evidence presents clearly that the tradition goes back to the early Protogeometric period (11th BCE) of the Iron Age and possibly beyond. Of course, ancient Greeks were not the only ones who had such customs; various civilizations that flourished in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and many others located in different regions had similar practices as well. Yet, our focus will only be set on ancient Greece for the purpose of this article.

Ancient Greek funerary rites were composed of three main sequential phases; prothesis, ekphora, and burial. Mourning and lamentation were among the most essential elements of the prothesis. One who prepares to cross Styx would be laid out on a kline (funeral bier) and women would clean, anoint, and often decorate his/her body with flowers. Attendants and the household would then begin engaging lamentation in standing or kneeling position around the voyager. In most cases, these lamentations were orchestrated by an elder within the household who would harmonically lead other women so the dirge would continue without interruption.

Terracotta Krater, Mourning and Funeral Procession, c. 750–735 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Artstor.

There were also moirologists (professional mourners), eksarkhos gooio, who would be hired by the family and become the chief mourner to perform a proper lamentation. During these lamentations, the sorrow of loss would naturally impel the attendants to cry—and even some to beat their own chests and attempt to rip their hair. In the second part, ekphora, the voyager would be escorted from his/her home to the burial site with a processional cortege. Depending on which social class the family belonged to, transportation of the body would be in an elevated manner where chariots and armed soldiers accompany the cortege. At last, burial or entombment would take place.

Among all these rites, women’s presence was undoubtedly dominant. Almost every act was conducted by them and no aspect lacked their influence. In her article published in 2018 on History Today, Patricia Lundy wrote; “the men kept their distance to salute the dead, physically signifying their separation from the realm that belonged to women.” Sakellaraki’s work affirms that modern women’s role—at least in some parts of the Earth—has identical aspects with the ancient way in the aftermath of a loss. Thus, by presenting this continuity via photography and other means of visual implementations, Sakellaraki’s project bears a neoclassical perspective. It derives its artistic strength through rendering a custom—with a glance of the 21st century— that has a classical root embedded deeply in Greek culture.

Plaque showing Prothesis Scene representing the Mourning of the Deceased, c. 560-550 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Artstor.

During my writing process, I was lucky enough to talk to Sakellaraki, and I asked her the following question:

Why do you think women came and continue to come forward as the chief figure in the aftermath of loss/death particularly within the Greek society and surrounding regions?

Sakellaraki answered: Overall, the topic of Women and Death in Greece has been explored by various thinkers attesting to the strong position of the lament from antiquity via the Byzantine era to contemporary society. Maniot women specifically are very proud of lamenting their dead. To sing laments is not something one can learn, ‘’it is in one’s blood’’, which requires certain verbal and musical skills.

The laments themselves are usually passed from mother to daughter. They are sung by the women of the house, the closest neighboring women, and often professional lamenters, in some cases. As Margaret Alexiou explains in her book, they are usually divided into three stages: they are sung in the traditional wake in the house before the burial, during the burial procession, and at the tomb. Afterwards, laments are sung in fixed intervals. The laments constitute a ritual that is considered a social duty in most of those villages.

Ioanna Sakellaraki, Moirologia from The Truth is in the Soil project, 2018. Courtesy of the Artist.

Throughout the various mortuary rituals, as Sourvinou-Inwood observes in one of her books, the participation of women was substantial as they were the ones preparing the body, whereas the burial ceremony itself was carried out by men because it is considered to mark the termination of “the period of abnormality and restored order”, (inhumation or cremation, grave digging, and tomb construction).

Women’s discourse in Greek society has been traditionally controlled and restricted by strict sociocultural codes. Barred from participating in the exclusively male public political scene, women may have developed another mode of expressing their concerns and opinions about the world around them—through performance of ritual laments. In his study “Silence, Submission and Subversion: Toward a Poetics of Womanhood,” Herzfeld argues that through agony women convert the disadvantages of their silent and mute position in a creative way. Based on this interpretation, we could see the ritual laments [as a] demonstration of the women’s influence in the practical performance of the death cult and the solidarity between women during the ritual.

Ioanna Sakellaraki, Aletheia from The Truth is in the Soil project, 2020. Courtesy of the Artist.

Dad is dead, come back home.

Alas, this was how Sakellaraki found out about the death of her father over the phone from her sister. In 2016, the year she lost her father, she returned to her homeland Greece to attend the funeral after spending a decade abroad working towards her studies and career. Hence, the emotions and thoughts she was experiencing during her time in Greece gave rise to The Truth is in the Soil, a long-term photographic project. Of course, this type of project was bound to have particular personal elements, which I believe is another strength, as these elements make the project even more special and unique. They form the departure point, but the scope of the project is not merely limited to these personal elements. The extent of the scope is enough to be embraced by many—we have all either lost or will lose someone we love at a certain point in our lives. This truth makes the project a universal one; although the structure may change, we all mourned or will mourn in some ways.

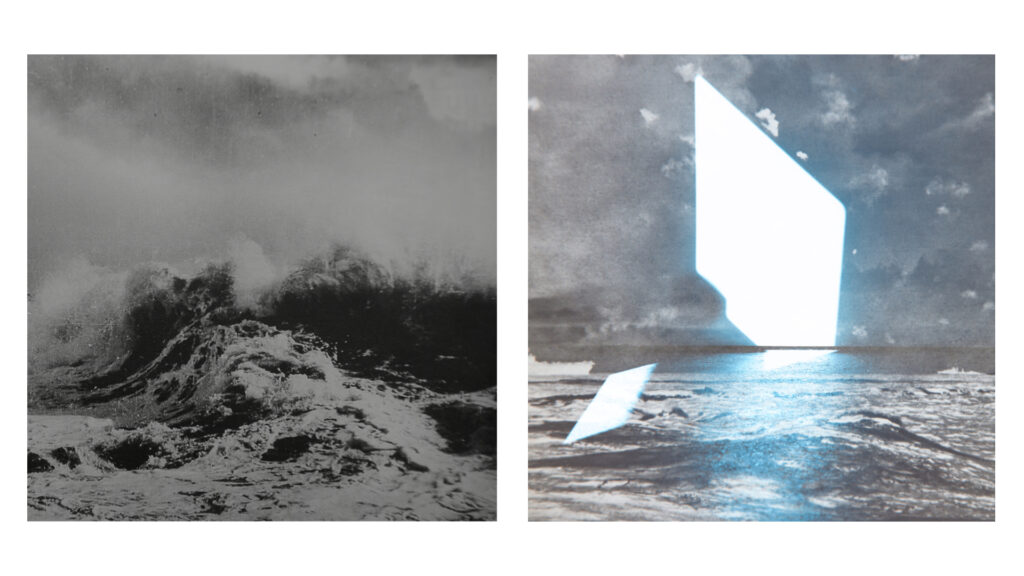

Left: Ioanna Sakellaraki, Thalassa, 2019. RCA; Right: Ioanna Sakellaraki, Moira Thanatoio from The Truth is in the Soil project, 2019. Courtesy of the Artist.

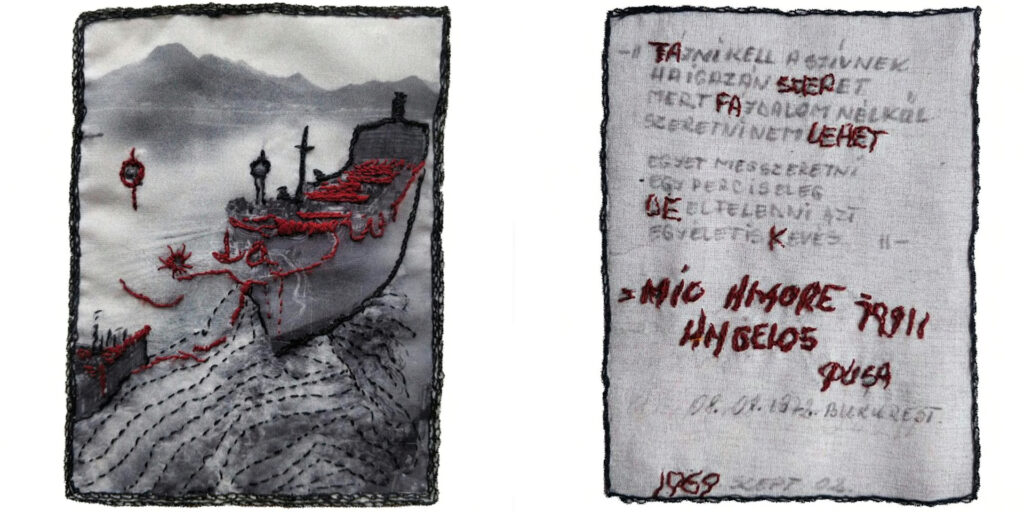

When I thoroughly observe the artistic perspective that Sakellaraki adopted and applied within this project, there was one specific thing I felt like I was exposed to: a serein. It is a meteorological phenomenon where it rains calmly even though the sky is clear and there is no single visible cloud. Her approach feels abstract yet tangible at the same time. One can mostly make sense of what the artist was aiming for, but these straightforward characteristics never nullify the aspects that let the observer’s mind interpret open-ended elements without any compulsion. On the other hand, her artistic versatility keeps the focus and mind of the viewer stimulated. We see a remarkable range of approaches and techniques in the project. From integrating hand-stitch embroidery on old photographs from her father’s archive to physically interacting with and transmuting the space that will appear in the frame in a unique way, Sakellaraki’s passion and love for this project overflows from its every element.

Left: Ioanna Sakellaraki, Memory of a Journey, 2020. RCA; Right: Left: Ioanna Sakellaraki, Letter from Puşa, 2020. RCA.

Besides my humble observations, I also have a brief description from Sakellaraki herself that presents the purview of the project. Here is how she worded it:

My work, The Truth is in the Soil, aims to look at how the work of mourning contextualizes our modern regimes of looking, reading and feeling with regards to the subject of death in Greece today. In the process of documenting photographically their communities, my readings and inspiration from the ancient Greek laments as gradually vanishing historical marks, made me question to what extent we see ourselves as subjects of history and how mourning can become a cultural experience of loss today.

Ioanna Sakellaraki, Eros from The Truth is on the Soil project, 2016. RCA.

At the beginning of the article, I pointed out that it wouldn’t be inaccurate to situate Sakellaraki’s project within the neoclassical sphere, for it is exploring and conveying the remains of a specific classical custom via photography. She also enriches this neoclassical propensity even more with her way of storytelling. We encounter instances where viewers may only appreciate the entirety of what was captured if he/she knows enough about certain ancient references that appear in ancient literary sources. Her storytelling often relies on concepts and realms within ancient Greek belief structure, such as Tartarus and Erebus.

One of the other symbols she uses is pomegranate, an allusion to Persephone and her fate. In another instance, she presents pomegranate as a storytelling medium again, but with reference to a different mythological figure, Adonis, whose fate converges at some point with Persephone and who is mourned deeply by Aphrodite. The usage of all these characters and places that are related to death, void, and mourning makes the entirety of the project timeless, as these classical elements are an everlasting part of us as humanity. Ultimately, the Truth is in the Soil comes forwards as a project where Sakellaraki brilliantly homogenizes the classical legacy of Greece, communal and personal reaction before death, and her artistic touch.

Ioanna Sakellaraki, Self Portrait. Courtesy of the Artist.

If you like the project and wish to support the artist, Ioanna Sakellaraki has recently turned her 5-year photographic journey into a very special photo book. I highly recommend everyone to check it out ! On the other hand, there are two solo shows on the horizon for the project. Mark your calendar if you are going to be in the area.

♦ March 2022, The Truth is in the Soil, Belfast Exposed, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

♦ 2022 (exact date to be announced), The Truth is in the Soil, Reminders Photography Stronghold, Tokyo, Japan.

Lastly, here are the Instagram and Twitter pages of the artist if you don’t want to miss anything about her future projects.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!