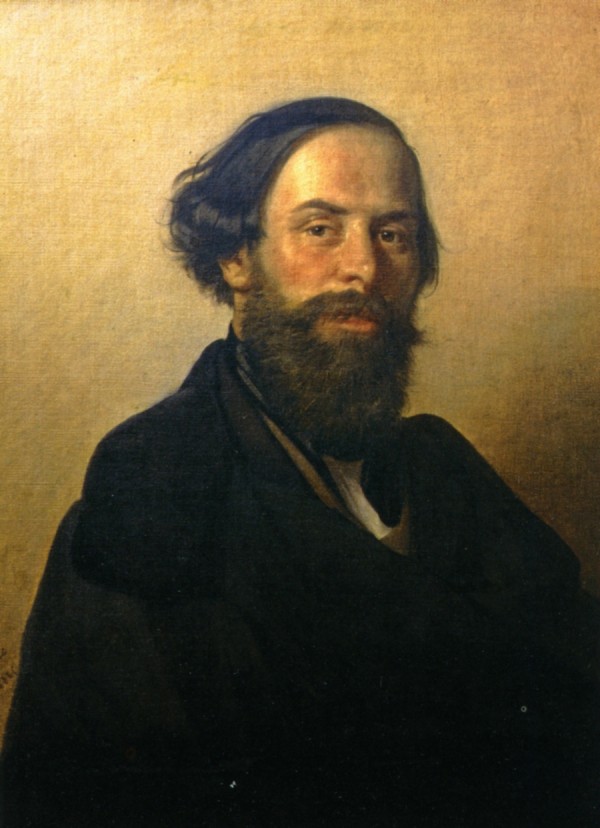

Early Life

Born in Belluno in the Eastern Dolomites, the Italian artist Ippolito Caffi embarked on a creative journey that would distinguish him from his contemporaries. The foundation of his artistic prowess was laid at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, a renowned institution that shaped his vision and technique. Caffi’s burgeoning talent garnered numerous awards during his time at the academy.

Ippolito Caffi’s Mature Career

Later in his career, Ippolito Caffi made a pivotal move to Rome. There, he solidified his reputation through not only his artistic endeavors but also through a treatise on perspective that showcased his deep understanding of the principles governing visual representation. His contributions extended beyond the canvas, as he delved into investigations on Roman archaeology, further establishing himself as a figure of scholarly distinction. In 1843 he also had the opportunity to travel through the Mediterranean and the Near East.

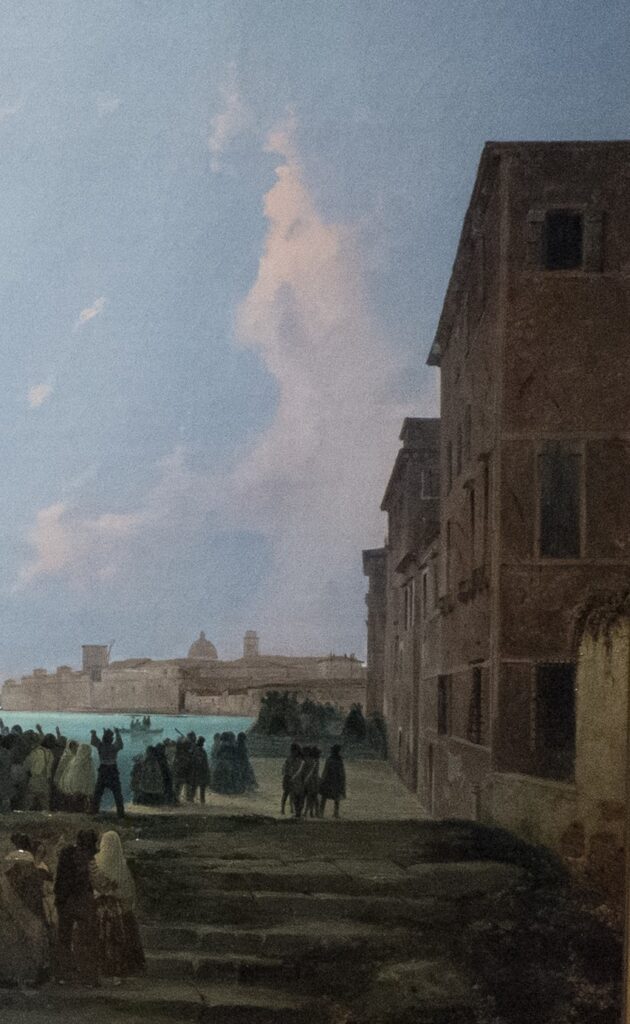

His first significant work was that of the Carnival at Venice. This was exhibited in 1846 in Paris where it was admired for its brilliant effects of light. His other works demonstrate his remarkable talent in vedute.

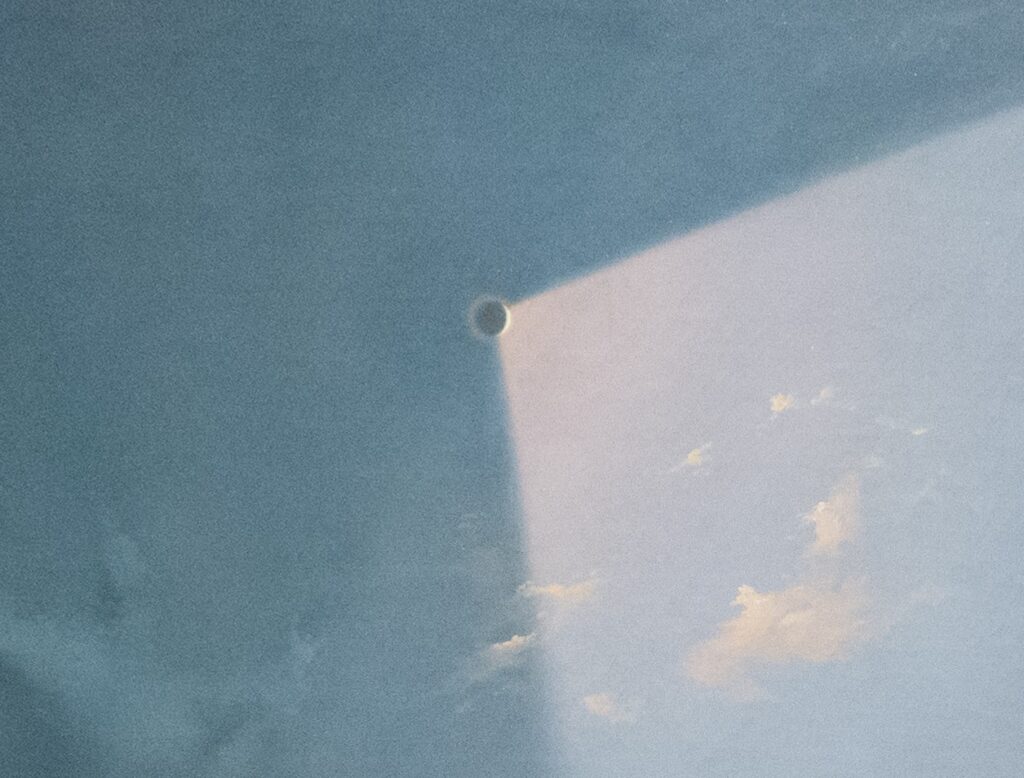

The Solar Eclipse of July 8, 1842

The eclipse observed on July 8, 1842, had a great impact on Ippolito Caffi and he found himself enthralled and completely consumed by the celestial display. Within weeks following the event, Caffi had completed this rendering to convey it to his teacher and confidant, Antonio Tessari.

Captivating Astronomical Event

This celestial event held a unique significance in the annals of astronomy. The last recorded eclipse had occurred in 1816, rendering the 1842 occurrence the first observation opportunity for a new generation of astronomers. Recognizing the rarity of this celestial phenomenon, the artist seized the chance to not only portray the astronomical event itself but also to capture the astonishment and curiosity etched across the faces of its Venetian observers.

Artistic Liberty

The painting, however, faced criticism for scientific “inaccuracies.” The depiction of the eclipse, unfolding from a vantage point in the northeast of Venice, raised eyebrows due to its unusually wide perspective. Critics noted the expansive view and the fan of sunbeams emanating from the slender crescent of the sun, aspects that deviated from the visual perspective of a total eclipse.

Depiction of the Motion

While the integrity of accuracy was called into question, it is plausible that the artist deliberately compromised it for dramatic effect. Employing artistic license, the painter aimed to convey not just the scientific precision of the celestial event but also the emotive impact of the awe-inspiring spectacle. He may also have been attempting to capture the “motion” of the shadow of the moon sweeping across the landscape in the instant of totality.

Near Precise Placement of the Sun and the Moon

Despite facing scrutiny for inaccuracies, recent scientific calculations have shed light on the nuanced details of the depicted celestial event. The precision of the sun and moon’s positions, as well as the duration of totality lasting one minute, has been scientifically determined. It becomes evident that the timing and positions in the artwork do not align precisely with the scientific data but are remarkably close to the actual event.

Historical Record

Beyond its artistic significance, the painting also serves as a historical document, preserving the memory of a rare celestial occurrence. Completed just three weeks after witnessing the total eclipse of July 8, 1842, it stands as a testament to the artist’s ability to encapsulate the essence of a moment, both scientifically and emotionally. In its fusion of artistry and scientific observation, the painting becomes a unique intersection of aesthetic expression and historical record.