5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

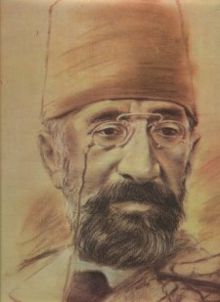

The first and last Orientalist painter of the Ottoman Empire is Osman Hamdi Bey. Born in modern-day Turkey, educated in Paris, and highly regarded as an intellectual, he depicts the Islamic society of his time with a view from within. His works are tranquil depictions of men or women set in exotic scenery. He satisfies the Western viewer’s expectation of an oriental atmosphere while remaining true to his beliefs and values.

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910) was a very interesting character in the Ottoman Empire society in the second half of the 19th century. His father was Grand Vizier, the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. After that, he served as Minister of Interior and was later appointed ambassador to Berlin and Vienna. Hamdi studied law in Istanbul, and in 1860 went to Paris to continue his studies. However, meeting the French Orientalist painters Jean-Léon Gérôme and Gustave Boulanger derailed his plans. He began studying painting under their guidance. He remained in Paris for nine years where he also studied archeology, visited museums, and participated in cultural and social Parisian life.

He exhibited three paintings at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle. Unfortunately, all three are lost today, nor do we have any photographs of them. His work gained recognition and he continued his career as an Orientalist painter, even after his return to Istanbul (Constantinople) in 1869.

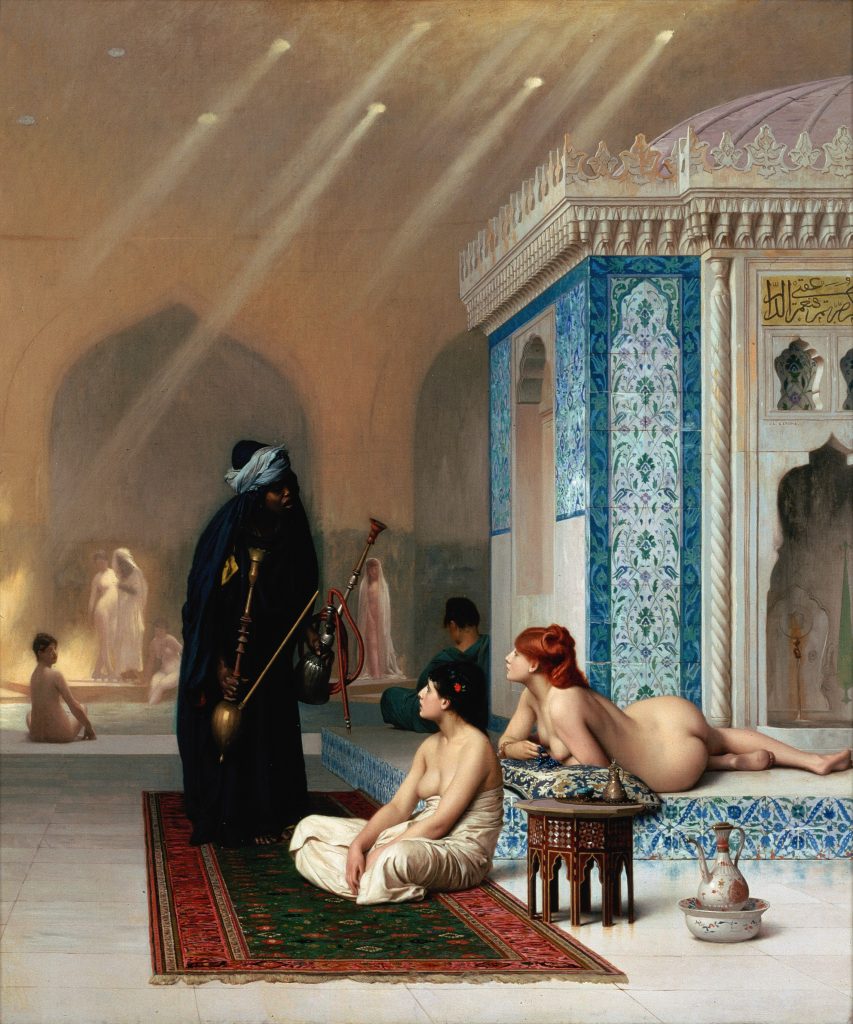

Orientalism, one of the subjects of 19th-century Academic art, came from the fascination of Western artists with other cultures. The Islamic world was for them what some only heard of in stories or saw in photographs. It was a land of enchantment, with beautiful women loosely dressed in the harem, exotic food, mesmerizing smells of spices, hypnotic rhythms of music, and incredible architecture with colored tiles. Later, art historians identified two types of Orientalism – the Realists, who painted what they saw with their own eyes, and those who only imagined the scenes they depicted. Jean-Léon Gérôme, Hamdi Bey’s teacher, traveled in 1853 to Istanbul. His encounter with Hamdi must have been a great pleasure. He was interested in having a student that came from the very world that fascinated him.

Osman Hamdi Bey was, and still is, the only Orientalist to come from the Orient. As a result, his paintings should be the most credible and authentic of them all. In a sense, they are. He represents his characters in real locations. In Ladies Taking a Walk, we can see the walls of Sultan Ahmet Camii, known as the Blue Mosque, in Istanbul. He also respects the fashion of the 1880s, portraying the women dressed in a ferace (an overcoat) typical for Istanbul during that time. However, if we look closely and consider that Hamdi Bey exhibited and sold his art mainly in the West, we cannot oversee the fact that the scene strikingly resembles a Parisian walk on the Boulevard, even if his characters are strolling around the hippodrome. We can also note the colorful dresses of the ladies, intentionally made to satisfy the desire of Western viewers for an oriental color palette.

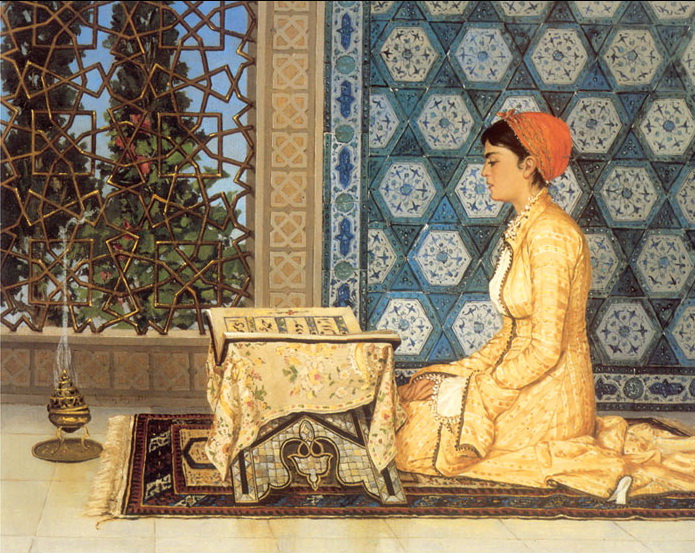

Beginning in 1880, we notice his works start having a central personage, more concretely a Muslim, but without the evidence of a certain specific role. Above is such an example in which he depicts a girl reading the Quran.

We see how he carefully composed the image to give the viewer as many Islamic elements as possible. The girl kneels on a beautiful oriental carpet. She reads from what we could suppose is a calligraphed manuscript of the Quran. The book is set on a rehal, which is an X-shaped book rest used for holding holy books during recitation. The rehal is one object Hamdi used in many of his paintings as an identifier of Islamic culture. The Bakhour incense burner is another object Hamdi strategically placed in front of the girl as a religious object of Muslim culture. Last but not least, the tiles on the wall, displayed in a beautiful regular geometric pattern representative of Islamic architecture, are sure to capture attention through their amazing color. The Mashrabiya, an Islamic lattice fence on the left, captivates through its intricate pattern.

Another example is the work above. Türbe was the word used for a tomb in the Ottoman Empire. However, in Arabic, the word can also denote a mausoleum. In this painting Hamdi portrayed a man entering a funeral chamber. Within it are two stone-draped sarcophagi, one with an empty turban pole, and one with a turban. The man stands in a position that we could identify as a prayer gesture. Hanging from one of the sarcophagi is a misbaḥah, prayer beads used to count in Islamic prayer. The walls of the room are filled with Islamic inscriptions that would have looked very exotic to the Western observer. Once again, the tiles are eye-catching with their deep blue hue.

Pera Museum in Istanbul holds two of the most famous of Osman Hamdi Bey’s works. Two Musician Girls illustrates young women playing the tambourine and a tambur (lute), traditional Ottoman instruments. They are in a corner room of the Yeşil Camii, (Green Mosque or Mosque of Mehmed I) in Bursa. Hamdi repeated here the same Islamic identifiers: the rugs, the beautifully painted tiles, the wooden workmanship, and the richly decorated interiors. What must be emphasized here is his approach to female identity. Unlike Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Pool in a Harem, Hamdi Bey never put emphasis on sexuality. The women in his paintings are always depicted in very decent, mundane situations. They appear fully clothed, playing an instrument, reading, or arranging flowers. This reflects the ideal of female beauty in Islamic culture and women’s role in society.

If you look closely at the multifoil arch behind the sitting girl, you will notice Hamdi Bey’s signature.

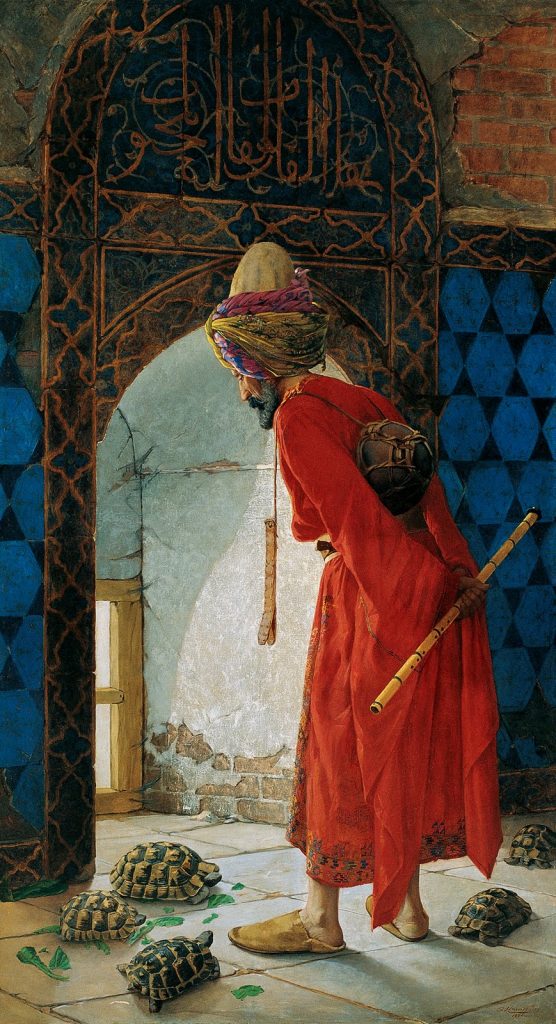

Finally yet most importantly, is the Turtle Trainer, Osman Hamdi Bey’s most famous work. The painting depicts a hodja (Muslim schoolmaster), dressed in a red dervish robe, with a turban on his head, and carrying a ney flute and nakkare drum. Five turtles are wandering around him. The old man is Hamdy Bey himself. The scene takes place in an upper-story chamber of Bursa Green Mosque.

Opinions about this painting are divided. Some suggest that it was inspired by a drawing, Charmeur de tortues. That piece was an illustration made by L. Crepon for Le Tour du Monde in 1869, after a Japanese engraving.

Others say the painting holds a deeper meaning:

“It subtly portrays this basic social message: that change is difficult, requiring much patience, in fact, the patience of a Sufi dervish. The five turtles in this portrait symbolize a stubborn, resistant, and slow-changing society. Some even believe that they represent the five most difficult associates of Osman Hamdi, giving him heartburn. The turtle trainer […] is Osman Hamdi, representing a patient intellectual that is coaching change. A change he hopes to teach primarily by blowing his ney and occasionally by using it to prod or reprimand the animals. Unfortunately, the turtles have no ears to hear the ney and with a thick protective shell, they are also not bothered by his prodding. His efforts are futile. Osman Hamdi Bey’s calls for westernization are met by deaf ears and much resistance by the establishment and the conservative segments.”

–Emin Pamucak, Osman Hamdi Bey’s Turtle Trainer. Light Millenium.

Later, in 1908, the painting became representative of the Young Turk movement and the revolution that forced Sultan Abdulhamid II to restore the Ottoman Constitution of 1876. This event ended the direct autocratic rule of the Sultan.

Osman Hamdi Bey remains the only Orientalist to depict the Islamic world from within, as an active member of Muslim society. Indeed, his works are obviously made to impress Westerners, while remaining true to his beliefs and values.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!