Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

In Italy, the abstract art period between 1930 and 1970 is characterized by five innovative movements: geometric abstract art, Arte Informale, The Azimuth Group, Spazialismo, and kinetic art. The artists associated with these movements – spanning a historical time marked by fascism, World War II, and the social and economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s – broke from earlier traditions to explore new aesthetic ideals and artistic forms leading to a rethinking of art itself.

Amidst the turmoil of the age, geometric abstract artists found balance through vibrant compositions of shapes and colors, while post-war Informale artists abandoned every connection with reality to focus exclusively on signs and patterns. The innovation continued with The Azimuth Group artists, who manipulated the canvas to let light bring artworks to life. The Spazialisti (Spatialist artists) projected art into space through forms and color and, in the most revolutionary artistic gesture yet, by slashing the canvas itself. Finally, Italian kinetic artists created works that interact with the viewer’s movement to produce fascinating visual effects.

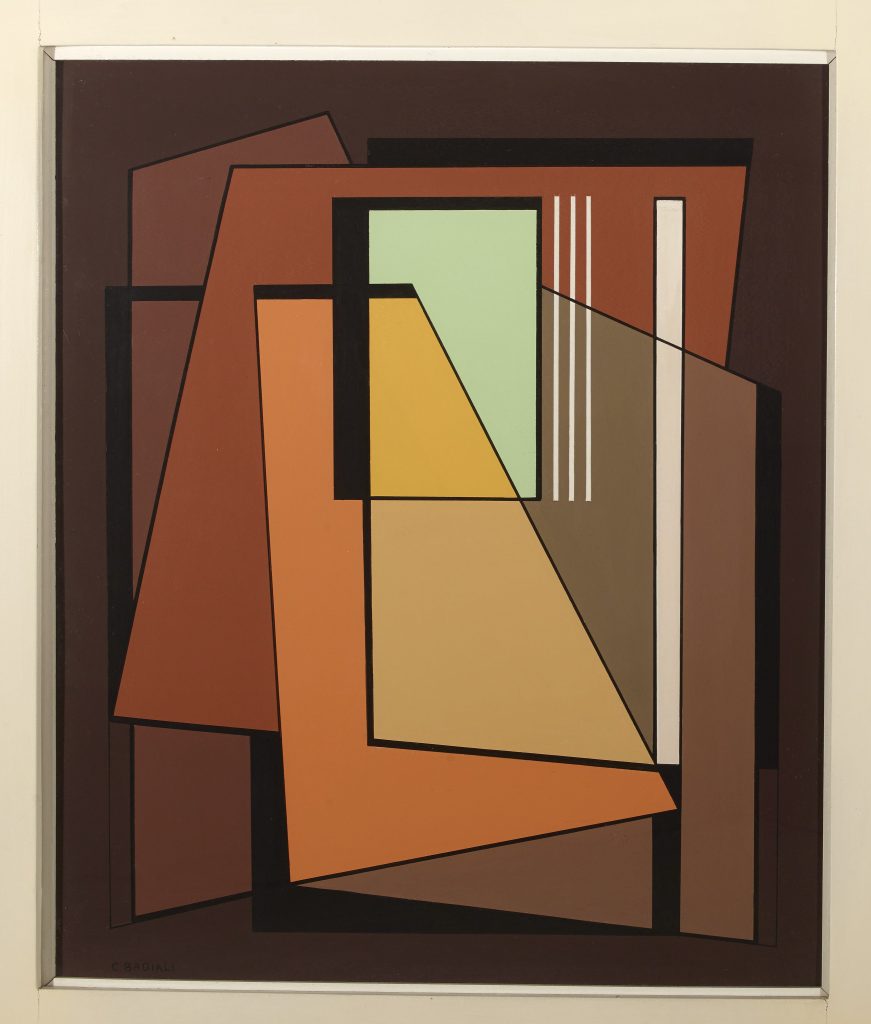

Carla Badiali, Composition, 1939, Museo del Novecento, Milan, Italy.

Geometric abstract art emerged in the 1930s thanks to an eclectic group of artists from the northern cities of Milan and Como, including Mauro Reggiani, Luigi Veronesi, Carla Badiali, Mario Radice, and Manlio Rho. In Milan, artists gravitated around the gallery Il Milione, which hosted exhibitions by contemporary European painters and sculptors. In Como, they studied the shapes and colors of the town’s thriving textile industry. They also collaborated with Rationalist architects like Giuseppe Terragni, who had abandoned traditional designs to build functional buildings characterized by clean lines and strong geometric forms.

Emilio Vedova, Cycle 62-B.B.9, 1962, Mart, Rovereto, Italy.

After World War II, artists continued to break with conventional notions of order and composition to create “art of another kind,” as French critic Michel Tapié called it in his 1952 book. This new movement, which in Italy was called Arte Informale, consisted of applying paint to the canvas in free-sweeping gestures, producing an effect of pure abstraction. The resulting works were even more removed from realism and figuration than previous trends.

Peggy Guggenheim, American art collector and niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, contributed to the success of many artists in this movement, including Emilio Vedova, Giuseppe Santomaso, and Tancredi Parmeggiani. By bringing American contemporary art to the 1948 Venice Biennale, she introduced Italian artists to movements like Abstract Expressionism and later supported them as they experimented with their own individual styles.

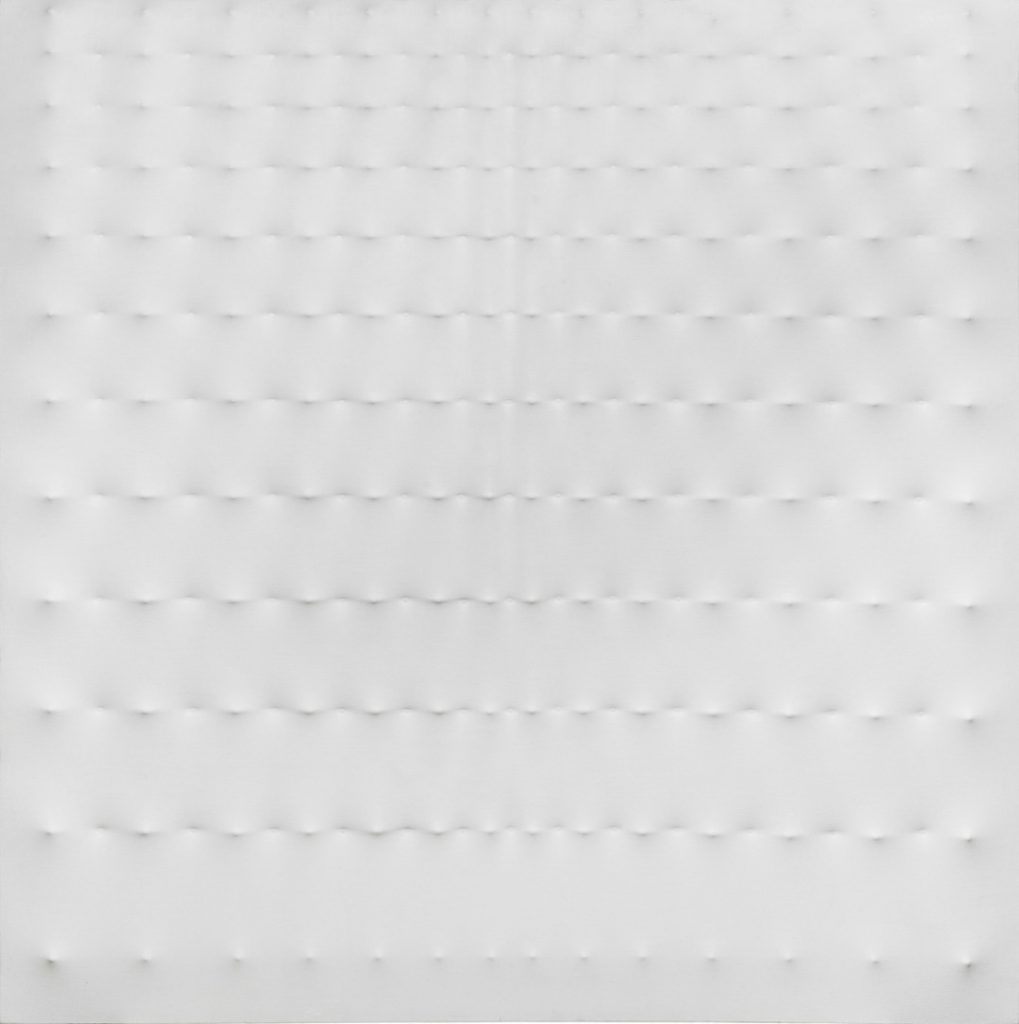

Enrico Castellani, White Surface, before 1968, Gallerie d’Italia, Milan, Italy. Photo by Valter Maino.

In the late 1950s, a group of artists writing for the Milan-based Azimuth journal distanced themselves from the experience of Arte Informale and advocated for a return to the form. They achieved this by shaping the white or monochromatic canvas in different ways. One of the artists from the group, Enrico Castellani, stretched the canvas on nails to generate constantly changing patterns of light and shade. Piero Manzoni soaked it in soft clay to obtain a colorless surface interrupted only by the folds and creases produced by the drying solution. Agostino Bonalumi turned his canvases into sculptures by shaping them with a range of materials.

Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept, Expectation, 1964, private collection. Sotheby’s.

Argentinian-born Lucio Fontana went even further in his experimentation. He punctured and then slashed the canvas to create his signature Spatial Concepts. These pieces are now displayed in major world museums and sell for millions of dollars. Slashing the canvas may seem like a simple idea today, but in the 1950s it was revolutionary. In a world characterized by new scientific discoveries, cosmic space development, and the advent of television, Fontana found a powerful way to express that expansion through his art.

Spazialismo, the art movement he founded in 1947, called for an art that embraced science and technology; “I don’t want to make paintings,” he stated in his Manifesto for Spatial Art, “I want to open up some space, create a new artistic dimension, connect with the cosmos, which stretches out infinitely, beyond the flat surface of the image”. Other members of Spazialismo were Gianni Dova and Roberto Crippa. Dova splashed liquid paint onto the canvas to create shapeless compositions that evoke the devastating potential of a nuclear explosion. Meanwhile Crippa’s signature paintings, elaborated spirals on monochromatic surfaces, recall the aerial acrobatics he did as a pilot, which eventually claimed his life.

Getulio Alviani, Vibrant Textured Surface, 1965, GAM, Turin, Italy.

The advent of television and other technological developments did not influence only the Spazialisti artists. In the 1960s, a new art movement known as optical or kinetic art emerged. While the works of The Azimuth Group artists relied on an interplay of light and shade for their varying effects, optical and kinetic art changed in appearance depending on the angle a viewer was looking at it. These variations create an illusory effect of movement that both confounds and fascinates at the same time. The main representative of this art movement in Italy was Alberto Biase, co-founder of the art collective Group N in Padua. Another artist, Getulio Alviani, created his first works of kinetic art with some polished aluminum surfaces found in the factory where he worked. Both artists were displayed in the groundbreaking 1965 MoMA exhibition on optical art titled The Responsive Eye, which marked an important milestone for Italian abstract artists abroad.

Author’s bio:

Roberta Garbarini-Philippe works in higher education administration at The City University of New York. She grew up in Italy, where she studied foreign languages and worked as an editor and translator before moving to New York. Her love of art started in the dusty archives of a book publisher in Milan. Many years later, she rediscovered that passion and is now pursuing a Master’s in Museum Studies at the CUNY School of Professional Studies.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!