Panamarenko steals from science and uses it in his art. He has designed planes and submarines that at first sight are perfectly capable of functioning, but don’t be misled: they are unique works of art that should be admired, not used.

The Inspiration Started with Choosing an Artist Name

Henri Van Herwegen (born 1940), student at the Art Academy of Antwerp, Belgium, pseudonymized himself Panamarenko, which is a contraction of “Pan American Airlines and Company” and the name of the Russian general Panteleimon Kondratyevich Ponomarenko (First Secretary of the Communist Party before becoming the Soviet ambassador to Poland). In some works, Panamarenko shortens his signature to ‘Panama’ and then writes his name in Cyrillic characters to give his work a more global look.

Ready…? Take off!

Although he studied at the art academy, he was mainly interested in natural sciences and technology. This interest would influence his entire oeuvre to this day, which raises the question: Is Panamarenko an artist or an inventor? The assemblages he makes are therefore often as technical as they are artistic. Most of his works are inspired by flying vehicles, ranging from zeppelins to UFOs, which is quite strange for an artist who says he doesn’t like flying at all. In interviews he confesses that he finds flying boring because you must sit still for such a long time.

On the other hand, this explains the imaginative appearance and the technical complexity of his works. You won’t be bored during the flight: In some works you will have to pedal to get ahead, in others you will enjoy a magnificent panoramic view under water.

In his own words, he made inventions based on the definition that existed until the middle of the 19th century. Nowadays, an invention is always associated with a pragmatic application. An inventor seeks and finds solutions to specific problems and the final work leads to a useful result. But when we go back in time, up until the middle of the 19th century, we discover a more versatile definition of the concept, where invention was strongly linked to imagination.

It is no surprise that Panamarenko’s concept of invention is similar to the old one. For him, invention is an adventure, a process of exploration. That is why he is often seduced by his imagination and the airships he builds in his studio become uncontrollable. “I built them all to fly, sail or drive,” he claims. Yet none of his vehicles do what they promise, and that is because he always adds complexity to them. At the end of the day, the work loses the original purpose. “My objects are becoming too beautiful to really function”, he explains.

Panamarenko began his artistic career in the 1960s. This was an extremely exciting period for the aerospace industry. In 1962 the Russian Yuri Gagarin completed the first spaceflight and 7 years later the American astronaut Neil Armstrong made the first steps on the Moon. That same year the French-British Concorde aircraft made its first supersonic flight.

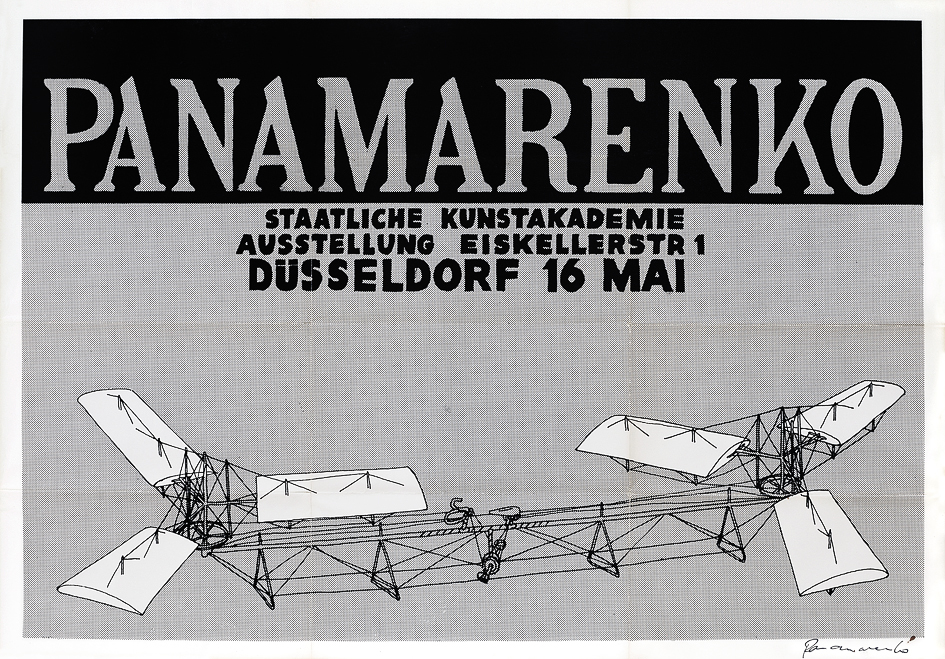

In 1967 he met Joseph Beuys in Düsseldorf, where Beuys was a teacher at the art academy. Beuys encouraged him to create his first flying machine, Das Flugzeug. After some designs on paper, Panamarenko started building his work. In this construction, an aviator sits on a saddle and rotates the blades on either side of the plane by pedaling like on a bicycle. His creation proved to be imaginative and beautiful, but it did not fly. The construction turned out to be too weak and the mechanism did not work.

The Aeromodeler

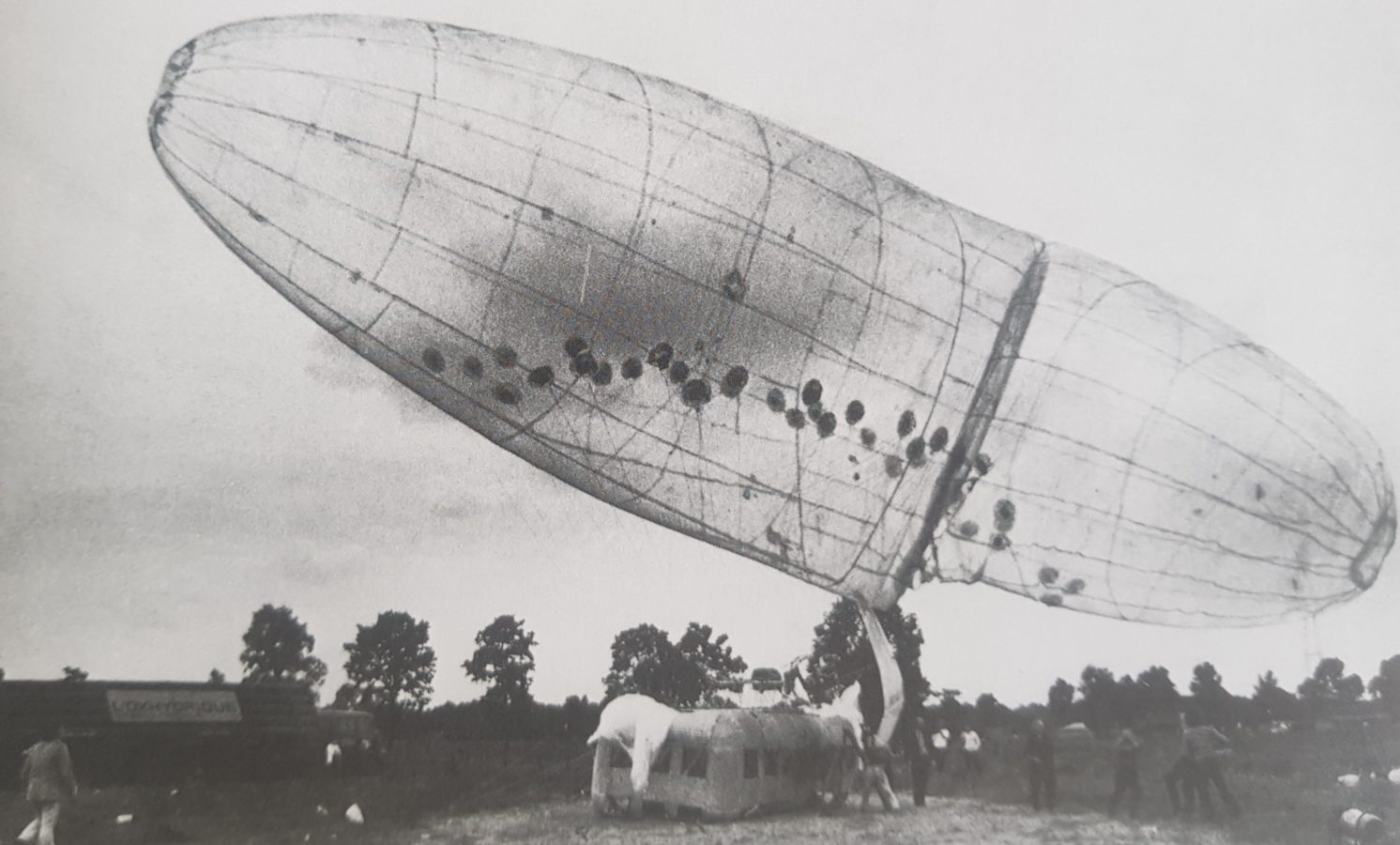

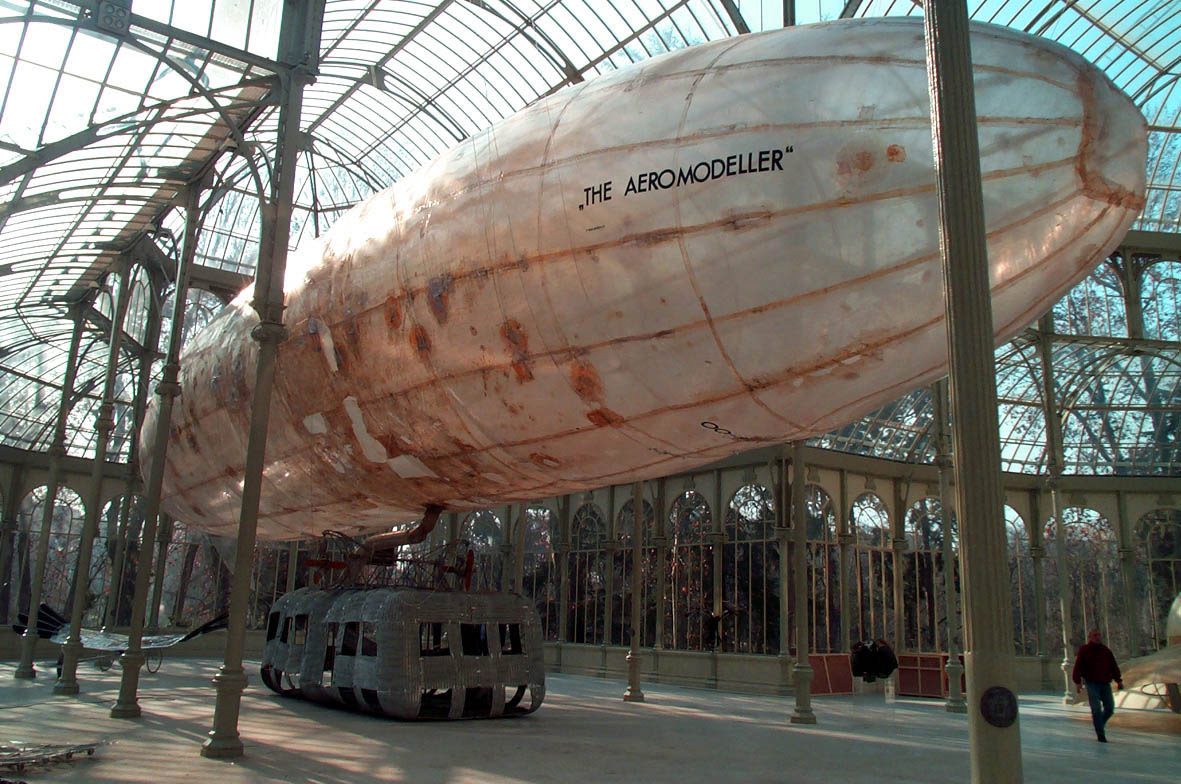

With Das Flugzeug in mind, Panamarenko started building one of his most impressive works and after 2 years, the zeppelin The Aeromodeller was presented to the public in 1971. The 28-metre-long zeppelin is made of glued strips of PVC film and the cabin underneath is a construction of rattan palm sprayed in silver. On top of the cabin there are two aircraft engines to control the impressive airship.

The airship embodies the artist’s dream of being able to move freely through the sky, which is why he designed the cabin as a private home. He planned to live there permanently in the air, preferably together with the French actress Brigitte Bardot. That never happened, and I strongly believe that having Brigitte Bardot on board was only a trick of his mind…

In 1971 Panamarenko tried to test the airworthiness of the zeppelin on the meadow of his friend-artist Jef Geys in Balen (near Antwerp). Its destination was the art event ‘Sonsbeek buiten de perken’ (Sonsbeek Beyond Its Bounds) in Arnhem, the Netherlands, about 120 km away. However, the crossing was forbidden by the Dutch aviation police, who informed Panamarenko of this by telegram. Being a rebel, he ignored the interdiction and made an attempt to take off. But this was in vain, for a storm above the meadow caused the attempted take-off to fail.

The Aeromodeller became however the icon of Panamarenko’s oeuvre. In the decades that followed, he built numerous variant models and prototypes for airships, each with different shapes, colors and proportions.

In 1980, the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art (S.M.A.K.) in Ghent, Belgium purchased the work. The reconstruction of The Aeromodeller took 2 days to assemble the cabin, to inflate the balloon and to hoist it above the cabin by means of pulleys and ropes. It took 18 people, each of whom had to pull ropes on each side to exhibit the zeppelin in all its grandeur.

Panamarenko’s desire to live as a nomad is also expressed in the flying boat Scotch Gambit. The first designs date from 1966, but it would take until 1990 before he made a full-scale model. Only in 1999 was the work finally finished.

007, Take a Seat Please

It seems to have come straight from the set of a James Bond movie: Scotch Gambit is an armoured vessel made of stainless-steel plates. The final aircraft is 16 metres long, 6 metres high and 9 metres wide. According to Panamarenko’s calculations it reaches a speed of 100 km/h and is equipped with two air-cooled 370-hp Lycoming aircraft engines and six cylinders.

At the back of the hull (which again serves as a lodging place) there is an opening with two large swing doors that give access to the ship. Inside, the walls are covered with duvets (he seems not to have been very sure about the aerodynamics of the ship) and there is a steering system that must be operated in an upright position. Q couldn’t have done a better job, wouldn’t you say?

On His Way to the North Pole

Panamarenko didn’t get very far by air, so he must have thought, “Why not try by sea?”. With this in mind, he designed the 6.5-metre-long steel submarine Nova Zembla. He wanted to use it to sail to the Russian archipelago carrying the same name in the Arctic Ocean. With the 20-kW diesel engine he should have been able to sail at a speed of 8 knots in 2 weeks from his hometown Antwerp to Nova Zembla.

The artist managed to create a submarine rich in poetry: The vessel has fins like a fish and blades like an insect. Fantasy, nature and science meet each other in this work and it is this kind of creation that makes him a unique artist.

The submarine is comfortably furnished with two couches and a small compartment for smoking a cigarette (according to Panamarenko, who was always ready for a joke). At the front you have an unobstructed view of life under water through the large window in plexiglass. In bright red Cyrillic letters, he signed his work “панама” (Panama).

Restoration Needed

The fragile construction of most of the works means that Panamarenko’s works have to be restored on time. For example, Airo Pedalo n°9 (1999) has already been restored because the work started to tilt. Such a restoration is carried out in collaboration with the artist or an assistant, but because Panamarenko did not work in a structured way during the construction process, it was not clear from which materials the work consists of and why it was collapsing. Therefore, in this case, X-rays were made of the mannequin that holds the parachute. When it appeared that the shoes of the mannequin were empty, the reason for the tilting was clear and the solution turned out to be a filling with cork resin. This is a malleable material which takes on the shape of shoes and breathes so that no rotting can take place. Furthermore, the plastic PVC, from which the parachute was made, was cleaned.

At a first sight, Panamarenko’s works of art seem to operate, but the artist’s imagination leads to vehicles that do not really function and moreover need to be restored in time. His art serves the ideal of beauty and the unlimited mind, not the useful, which would detract from these fine works.