Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

12 May 2024 min Read

Whistler’s 1871 painting Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1 might not sound familiar. As Whistler’s Mother, on the other hand, it has entered popular culture. The focus of a Mr. Bean film, the lyrics in a Cole Porter song, and a symbol of America and American art despite being permanently housed in Paris. Let’s look at its lasting appeal.

James McNeill Whistler, Whistler’s Mother (drypoint), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA.

Anna Matilda McNeill (1804–1881) grew up in North Carolina. At twenty-seven she married a friend of her father, widower and retired army officer, George Washington Whistler, who already had three children. Anna McNeill Whistler gave birth to five children, of whom only two survived into adulthood. In 1842, she and her three young sons, including James, accompanied her husband to Russia where he worked as a railway engineer.

After her husband died of cholera in 1849, Anna returned to America, living in much-reduced circumstances. At the suggestion of her stepdaughter, who was married to a British surgeon, Anna moved to Britain. For nine years from 1863, Whistler’s mother lived around the corner from the artist’s London studio.

She worked tirelessly to support her son’s artistic career and was proud of his achievements. A conservative and deeply religious woman, she seemed ignorant of, or deliberately blind to, his increasingly Bohemian lifestyle.

James McNeill Whistler, Self Portrait with Hat, 1858, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) was clearly close to his mother: he signed his letters to her ‘your fond though faulty son’. However, he never intended to paint her. A letter from Anna to her sister in November 1871, describes how she was a last-minute replacement for a model who had fallen ill. Whistler apparently greeted her with the words: ‘Mother, I want you to stand for me!’ And, of course, she was happy to do anything to help her son’s career.

Originally, it was a standing pose, but the elderly Anna found it too tiring. Everyone who knew her thought the final result was an excellent likeness, with the exception of the oversized feet.1 She firmly believed the portrait was a tribute to her, always referring to it as ‘my painting’. The irony is that this is opposite of Whistler’s intention.

James McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1862, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Whistler started giving his works musical titles from the late 1860s: symphonies, harmonies, variations, and a whole series of landscape nocturnes. He also started renaming earlier works, for example, The White Girl (1862), his portrait of Joanna Hiffernan, became Symphony in White No. 1. The portrait of his mother was the first of two ‘arrangements’ in grey and black. In 1873, he painted a very similarly composed portrait of writer Thomas Carlyle, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No 2.

Whistler wanted to distinguish his art from the narrative and symbolic content of much of Victorian painting, and from the detailed copying of nature championed by John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites. He wanted to create works which spoke directly to the viewer through emotion. If music did this in an abstract way through chords and melody, art could do the same through color and form.

James McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No 2: Portrait of Thomas Carlyle, 1873, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, UK.

In one sense, Whistler was looking forward to early 20th-century abstract artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky. In 1943, Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, described Whistler’s Mother as “a composition of rectangles”. Without the figure, he thought it ‘not very different from the abstract Composition in White, Black, and Red painted by Mondrian’.

However, for an artist in the 1870s, the final leap towards abstraction was inconceivable. Whistler came closest in his Nocturne in Black and Gold: the Falling Rocket. The work was so radical, and so vilified by art critic, John Ruskin, that it led to a libel trial in 1878. Ruskin had accused Whistler of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Whistler sued and the case helped to bankrupt him, effectively forcing him to pawn the portrait of his mother.

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, c.1875, Detroit Institute of Arts, MI, USA.

Whistler was not the only artist in the late 19th century to explore ideas of pure art. Art for Art’s Sake or Aestheticism was a movement that opposed the contemporary emphasis on narrative or moralizing paintings. For aesthetic painters, art was about beauty, emotion, and giving pleasure to the viewer. They wanted to break down barriers between art and design, and between the different art forms.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote poetry to accompany his paintings, creating ‘double works of art’. Whistler himself designed every aspect of the Peacock dining room at the house of his friend and patron Frederick Leyland. Synesthesia – the idea that the senses were interconnected – was an important part of Art for Art’s Sake. By using musical titles, Whistler was establishing his aesthetic credentials.

James McNeill Whistler, At the Piano, 1858-1859, The Taft Museum, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

One of the ways in which Whistler challenged traditional ideas of art was through composition. By using horizontal lines and a shallow picture space he moved away from conventional perspective. Whistler creates a very shallow foreground in which his mother sits, against a plain wall on which are placed two framed pictures.

His early 1858-1859 portrait of his half-sister, At the Piano, employs the same principles but less strictly. Here there are more interior details, like the gilt frames and the round table on the left. There is also a strong reflection in the righthand picture glass and a shadow under the piano.

In contrast, the portrait of his mother is almost entirely restricted to straight horizontal and vertical lines which create a two-dimensional grid against which the figure sits. We know that Whistler made precise compositional changes during painting, shifting the print to the left and lowering the sitter’s head and position of her knees. The balanced calm of the finished painting was not achieved by accident.

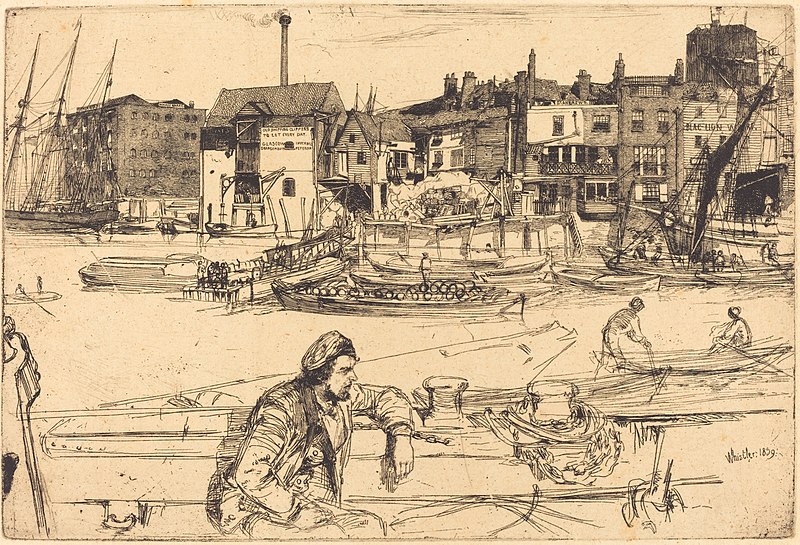

James McNeill Whistler, Black Lion Wharf, 1859, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Whistler’s limited palette was unusual. He began his career as a printmaker working in monochrome. His own 1859 etching, Black Lion Wharf, hangs on the wall by his mother. Equally, his early Realist works were often based on strong line and contrast.

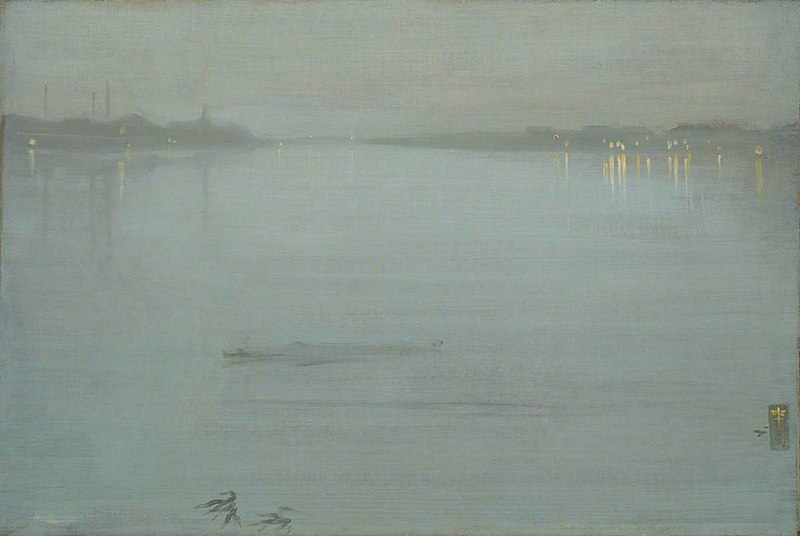

Increasingly, however, he was drawn in the opposite direction, experimenting with subtle tonal shifts in a limited palette. Whistler’s Mother combines strong contrasts between the figure’s dress, the black line of skirting, and the wall, with a softer mood generated by the varying greys of the floor, drapery, and background.

Whistler worked on an unprimed canvas which soaked up his paint. He used heavily diluted oils to build up semi-translucent layers of color and allow the canvas weave to show through. The result is fuzzy lines and blurred edges, which project an emotional softness.

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights, 1872, Tate Gallery, London, UK.

Japanese art and design were very popular in late-19th-century Europe. Whistler collected prints, textiles, and porcelain from Japan and China and featured them in many of his artworks. The drapery on the left of Whistler’s Mother has been identified as a kimono, the floor covering is Chinese matting and the chair is an English-made version of Japanese black lacquer furniture.

Japanese prints had only been widespread in Europe since the 1860s. They showed artists an alternative to Western traditions of perspective and chiaroscuro modeling. By including references to Far Eastern culture in his portrait Whistler emphasizes his status as a leading member of the Aesthetic avant-garde.

James McNeill Whistler, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, 1863-1865, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 was controversially accepted by the Royal Academy and exhibited in the 1872 exhibition. The Times reviewer’s reaction was typical: “An artist who could deal with large masses so grandly might have shown a little less severity, and thrown in a few details of interest without offense.”

It was shown in Paris later that year and Whistler sold it to the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, in 1891. It was the first painting by an American artist to enter the French public collection. In 1933 Whistler’s Mother returned to the USA, going on a nationwide tour by train. It was praised by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who saw it accompanied by his own mother when it was shown at MOMA.

James McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1871, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1 exemplifies Whistler’s ideas about art and Aestheticism. However, the enduring popularity of the painting lies more in the tenderness with which the frail but clearly strong-willed elderly woman is portrayed.

Despite the artist’s best intentions, the mother-son bond is subliminally conveyed through the canvas. As Rowan Atkinson cruelly put it in the film Mr. Bean: “It’s a picture of a mad old cow who he thought the world of”. That is the reason everyone remembers Whistler’s Mother.

Kathryn Hughes: “Whistler’s Mother review – a painting that’s not what it seems”, The Guardian, 12 May 2018.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!