5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Jan Matejko (1838–1893) is one of the most famous Polish painters. When he was in his twenties, he was twice awarded the gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris, where his paintings hung alongside the works of Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme. He is known to be the main painter of Polish history.

Matejko lived all his life in Krakow, where he studied at the School of Fine Arts (1852–1858) and where he chose historical painting as his specialization. In 1859, Matejko also received a scholarship from the School of Fine Arts in Munich. After returning to Krakow, he continued painting scenes depicting Polish history. His works were so important because in the nineteenth century Poland was partitioned, so reminding his compatriots of scenes from their national history served the purpose of “cheering the hearts” and it also fits into the pan-European fashion of historical painting.

Matejko’s first well-known work which he accomplished at school was The Shuysky Princes before King Sigismond III. This work, painted under the visible influence of the classicizing manner of his teachers, was to remind viewers of the tribute paid by the leaders of the Muscovite troops to the Polish king, Sigismond III, in 1611.

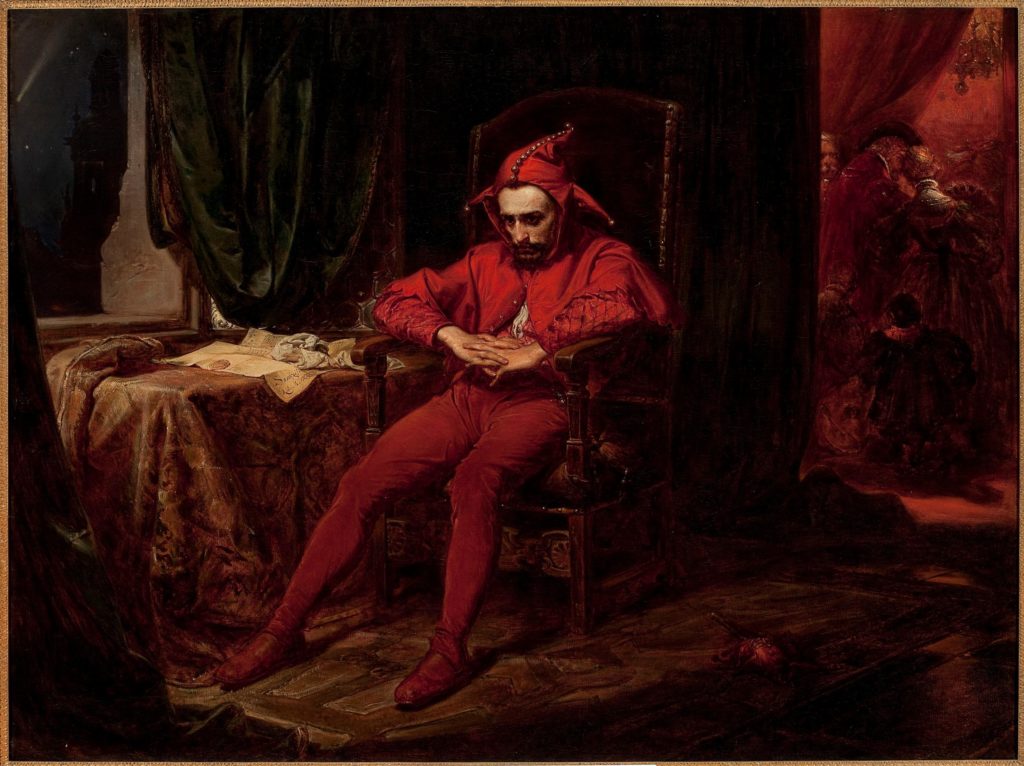

Another important painting is Stańczyk (1862). This was the name given to the court jester in Poland in the Renaissance era, during the reign of King Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548). At that time, Stańczyk not only performed the function of making the king laugh, but he could also afford to unofficially suggest advice to him.

On this painting we see a surprising moment – a jester is not saying jokes, but is sitting all alone clearly worried, while behind the curtain there is a company having a ball. He is sad because at exactly that time (in 1514) Poland was losing the city of Smolensk. The jester, therefore, seems paradoxically the only person who can afford seriousness in the face of the military defeat.

Rejtan, or the Fall of Poland (1866) depicts a protest against the first partition of Poland of Tadeusz Rejtan, a deputy in the Sejm (lower house of parliament) of 1773, known as the Partition Sejm, which was forced by the Russian army to accept it. There were three partitions altogether – in 1772, 1793 and 1795 – made by Russia, Prussia and Austria, as a result of which Poland disappeared from the maps of Europe until the end of World War I in 1918.

The tragedy of the scene depicted is deepened by the knowledge that it was only a prelude to the next partitions that followed.

Have a look at the woman in the portrait in the centre of the scene. This is the Russian Tsarina Catherine II.

Astronomer Copernicus or Conversations with God is the next canvas which again refers to the time of the Renaissance and presents the Polish contribution to the development of astrology. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), the author of the heliocentric theory, was the first man to discover that the Earth revolves around the Sun, not the reverse as previously thought. In the painting we see Copernicus observing the heavens from a balcony by a tower near the cathedral in Frombork (in the back) – the city where he lived.

Probably the most famous painting of Matejko is Battle of Grunwald (1878) depicting another event from Polish history, this time from 1410. It is the victory of the Polish-Lithuanian army over the Teutonic Knights. The painter placed historical figures on the painting. So, in the centre of the composition we see, among others, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Witold, and on the left the great master of the Order, Ulrich von Jungingen. The picture presents the moment victory is secured by the Polish-Lithuanian troops. Matejko placed the Polish king, Władysław Jagiełło, in the background on the hill.

Prussian Homage is another picture that deals with the subject of Polish-Teutonic relations. This time, we see the event from 10 April 1525, during which the last grand master of the order, Albrecht Hohenzollern, swore fealty to the aforementioned king, Sigismund I the Old. Then the state of the Teutonic Order changed its name to Prussia and the order itself was secularized. The tribute was the result of the dependence of this newly created state on the Polish-Lithuanian State. Interestingly, here we can see the figure of Stańczyk, who again does not share the generally prevailing enthusiasm, and we know why. The following historical events proved that the consent of King Sigismund to create a separate Prussian state was to have significant consequences. Prussia at the end of the 18th century became one of the invaders of Poland.

In the background on the left, we can see the Cloth Hall – a building located on the Market Square in Krakow, where this tribute took place over five centuries ago. The painting is now placed in a museum in the Cloth Hall.

Another image connected directly with the partitions was the Constitution of May 3rd, 1791. The creation of the constitution (the first in Europe and the second in the world after the American) by the Polish Sejm was the last attempt to prevent the partition. In the picture we see an enthusiastic crowd running into the cathedral of St. John in Warsaw, carrying on their shoulders the Sejm Marshal who holds the constitution high. The king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, dressed in a coronation dress, climbs the stairs to the church.

For Matejko’s viewers today, this scene was both joyous and tragic at the same time. The adoption of the constitution did not save Poland from being partitioned, and the king presented here was the last Polish king in history elected by Polish society.

A year before his death, Matejko painted for the second time Tsars Szuyski in the Warsaw Seym. In it, the painter returned to the subject of homage paid to the king of Poland by the then rulers of Moscow. After the victorious battle of Kłuszyn in Poland in 1610, the commander-in-chief, Stanisław Żółkiewski, was invited to the Kremlin, and the Russian boyars (aristocrats)wanted to pay homage to him. It was the only moment in history when Poland could take power in Moscow and King Sigismund III’s son Władysław could become king of Russia. The Polish king, however, did not agree to Władysław’s transition to Orthodoxy. In this way, the opportunity was lost and Russia, as well as Prussia, became one of the partitioning powers at the end of the eighteenth century.

Apart from the historical value of Matejko’s paintings, their style is also important. As you can see, from the first image of the Szuyski canvas to the second one, his style evolved from classicist to almost impressionistic. His shots are nearly cinematic, the emotionality of the scenes being just about striking.

Interestingly, although Matejko’s paintings are populated with real historical figures, some of them are placed there against the historical truth. Matejko did it on purpose, in order to emphasize the work’s message and include as many contexts as possible.

Matejko’s paintings are extremely important for Polish culture, and his Gallery of Kings and Princes of Poland determined the iconography of Polish rulers. His paintings have become an iconic reflection on historical events and helped shape the imagination of subsequent generations of Poles.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!