5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

During the mid-19th and 20th centuries, Western art saw the birth of Japonisme. The term was coined by Philippe Burty in 1872 and refers to the craze of Japanese culture in Europe. At a time when artists started to reject traditional art-making, Japanese aesthetics seemed like a breath of fresh air. They loved its flatness, vibrant colors, depiction of nature, and stylization. It inspired them to try new techniques, compositions, and themes. Now, let’s take a trip through art history and see how Japanese art influenced Western art.

The year 1867 was the start of a new era for Japan. During the Tokugawa or Edo period (1603-1867), their authorities feared any sort of foreign influence. Therefore, they isolated themselves. However, the stability started to crumble and Western pressure to open commerce, especially from the United States, grew. Furthermore, the samurai’s economy weakened and they orchestrated a coup. As a result, the emperor regained his power and changed the way of administrating the country. Consequently, the fears of the former regime became true and the country suffered Westernization. However, the West did not remain immune to Japanese influence either.

In 1854, the Japanese ports reopened for Western ships. As a result, objects and artworks traveled to Europe, fascinating everyone. For example, fashion came up with the “pagoda” dress, inspired by the architectural form of some Asian cultures. Moreover, interior design introduced Japanese elements into people’s homes. And, who can forget the famous Madame Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini which premiered in 1904 in La Scala? The opera was based on works of literature. The sources were the novel Madame Chrysantheme by Pierre Loti and the short story Madame Butterfly by John Luther Long.

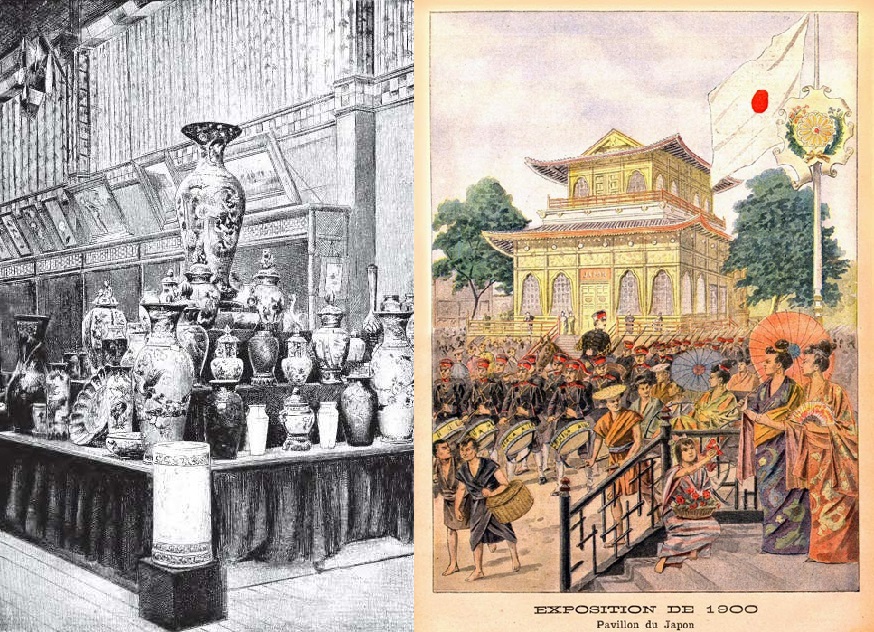

Some objects appeared in large exhibitions such as the World’s Fair in Paris and Vienna. However, others arrived with much less pomp and circumstance. For example, James McNeill Whistler discovered prints in a Chinese tea room on London Bridge. Regardless, Japanese art and culture influenced both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism and beyond.

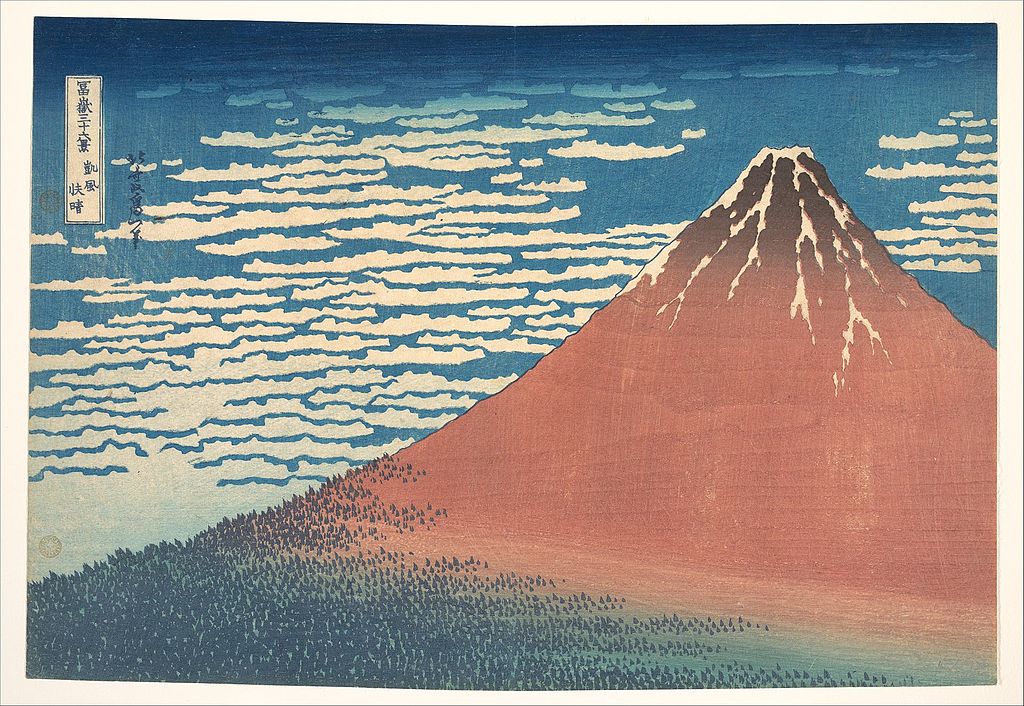

One of the most influential styles was ukiyo-e, meaning images from the floating world. This was a traditional form of woodblock print from the Edo period. It depicts hedonistic scenes from urban society. For example, among the various themes are courtesans, Kabuki actors, and romantic landscapes.

Claude Monet was one of the Impressionists most visibly inspired by Japanese art. Apparently, he saw ukiyo-e prints for the first time as wrapping paper in Holland. In fact, he painted his wife as a woman wearing a kimono and surrounded by Japanese fans. Of course, his famous garden reflects his love for that culture. Furthermore, he collected dozens of prints that still decorate his house in Giverny, France today.

Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas also represented Japonisme. Rather than depicting Japanese subjects, both friends adopted Japanese techniques to their works. Subsequently, Cassatt moved away from tridimensionality and used flat colors to represent scenes of women’s lives instead.

Meanwhile, Edgar Degas exposed his Japonisme through his famous dancers. In Japan, there was a fear of fullness, which contrasted with the Western fear of emptiness in art. Therefore we can see big spaces with nothing but flat colors. Additionally, he incorporated asymmetry into his compositions. Just take a look at the painting below. In the academic tradition, the dancers would have been placed at the center of the canvas, the perspective would have been perfect and we wouldn’t be seeing those flat colors.

Without a doubt, one of the Post-Impressionist painters most representative of Japonisme was Vincent van Gogh. Actually, he wouldn’t stop talking about it in his letters to his brother, Théo.

All my work is a little based on japoniserie, (…) Japanese art in decline in its homeland takes root in French impressionist artists.

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Théo van Gogh, Arles, 1888. Art d’histoire.

Indeed we can see the influence in his paintings. For example, in this portrait below of Julian-Francois Tanguy (1825-1894). Tanguy owned an art supply shop in Paris and helped many artists by showing their works, including Van Gogh. Furthermore, it was in this city where van Gogh met Japanese art as well as Impressionism. The background in this portrait consists of various Japanese prints.

In fact, he was a great admirer of Hokusai and Hiroshige. Sometimes he even made copies of Japanese artworks.

Van Gogh’s friend Henri Toulouse-Lautrec was another follower of Japonisme. Later on, his famous posters drew from Japanese techniques, silhouettes, flat colors, diagonal compositions, and cut-off images.

It’s no surprise that Art Nouveau and Japonisme went hand in hand. Siegfried Bing, the owner of the art gallery Maison de l’Art Nouveau, was an important promoter of Japanese art. He not only exhibited paintings but everyday objects taken from Japanese aesthetics. Moreover, Bing commissioned works from the Nabis artists such as Ker-Xavier Roussel, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis.

What we are trying to do is what the Japanese have always done and no one can imagine machine-made arts and crafts in Japan.

Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, The Work-Program of the Wiener Werkstätte, 1905. Coursehero.

For the artists of the Viennese Secession, Japanese craftmanship contrasted with Western industrialization. They wanted to return to a time when everything was made with care and dedication, not modern mass production. In this way, they shared with Art Nouveau the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, meaning the total work of art. For this, nature is the ultimate example. Furthermore, they were drawn to the elongated forms, the verticality of the compositions, the flatness, and the abstraction of Japanese works.

No one was crazier for Japanese art than Gustav Klimt. He not only applied those elements to his works but even dressed in a sort of kimono and collected prints. Certainly, his paintings do feel like floating worlds.

So, this is how Japan took over Western art. It started with academic paintings of women wearing kimonos surrounded by Japanese objects. Later the artists reached an internalization of Japanese aesthetics in the Viennese Secession.

Japanese art is important as a teacher. From it, we once again learn to feel clearly how far we have strayed from nature’s true designs through the persistent imitation of fixed models; we learn how necessary it is to draw from the source; how the human spirit is able to absorb a wealth of magnificent, naive beauty from the organic forms of nature in place of pedantic, decrepit rigidity of form.

Julius Lessing, report from the Paris Exposition Universelle, 1878. Art Nouveau Club.

Colta, Ives. “Japonisme“, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved on July 19th, 2021.

Dr. Cramer Charles and Dr. Grant Kim, “Japonisme“, Khan Academy, Retrieved on July 19th, 2021.

Eschmann Marie-Joelle, “Japonism: This Is What Claude Monet’s Art Has in Common with Japanese Art“, The Collector. Retrieved on July 21st, 2021.

“Floating Worlds: Klimt X Japan.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved on July 24th, 2021.

Martin Matthew, “From Japonisme to Art Nouveau.” The Art Nouveau Club. Retrieved on July 21st, 2021.

Martinot Lise, “Japonisme 1/2 Histoire d’un plagiat?“, Art d’histoire. Retrieved on July 20th, 2021.

Martinot Lise, “Japonisme 2/2, van Gogh, Degas et Lautrec“, Art d’histoire. Retrieved on July 20th, 2021.

“Meiji Restoration“, Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved on July 19th, 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!