Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

16 February 2025 min Read

Although representations of Black people were overlooked in European art for a long time, current social and political movements participate to reanimate the interest in some of these artworks. The Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley is one of them. However, this painting is not just one of the rare portraits of Black people in the Western art tradition. Behind its apparent simple composition, it turns out to be much more complex than it looks, similar to the historical period it illustrates. Let’s (re)discover it!

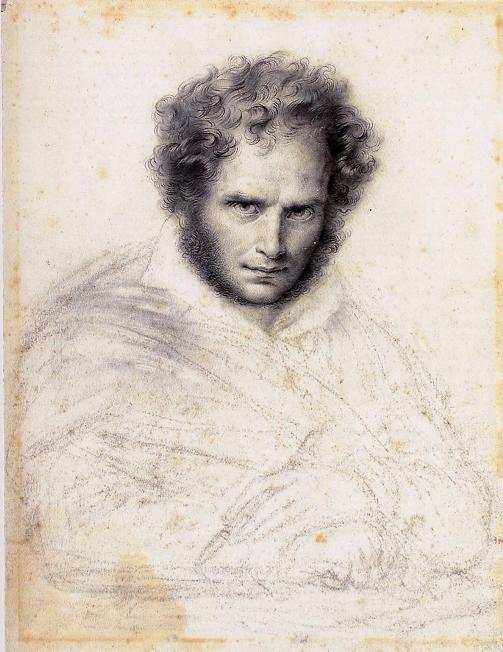

Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson was a French painter during the 18th and 19th centuries. He was certainly the best pupil of Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, who himself embodied artistic perfection for a long time.

In 1789, Girodet-Trioson won the Prix de Rome – a prestigious distinction in which the winner got to study in the Eternal City – by presenting Joseph Recognized by His Brothers. The biblical theme of the painting, its theatricality, its reference to antiquity as well as its mathematically balanced composition made it a Neoclassical Davidian creation.

However, after he returned from his trip to Italy, Girodet-Trioson broke with the cold seriousness of Neoclassicism. He started to develop a more intimate and sensual style, making him one of the pioneers of Romanticism. The portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley was made during the painter’s transition from the Davidian style to Romanticism.

Another important detail of Girodet-Trioson’s life is that he received a savant education, strongly influenced by the Enlightenment and its ideals such as liberty and equality for all. This may be why he portrayed Jean-Baptiste Belley. The truly romantic journey of this man, who literally fought for his freedom and the abolition of slavery may have inspired the humanist artist.

Jean-Baptiste Belley was the first Black man to hold a government position in French history. Born around 1746 in Gorée, the infamous slave trade island just off the coast of mainland Senegal, he was separated from his family and sold as a slave while he was still a baby. Deported to Saint-Dominque, modern-day Haiti, Belley regained his freedom in 1764. Living as a free man, he owned a wig business, but he is mostly remembered for being an incredible soldier.

Like a lot of former slaves, Jean-Baptiste Belley fought in the French army during the American War of Independence. Belley actively took part in the Haitian Slave Revolt led by François-Dominique Toussaint-Louverture where all Black people, free men or slaves, demanded their hard-earned independence, being the first of its kind in history.

Though the concept of Black excellence didn’t exist yet, Jean-Baptiste Belley strived to gain his freedom and that of all of the other Black people from the French colony. It is a natural consequence then that he was elected deputy to represent the French colonies in Paris regarding the abolition of slavery.

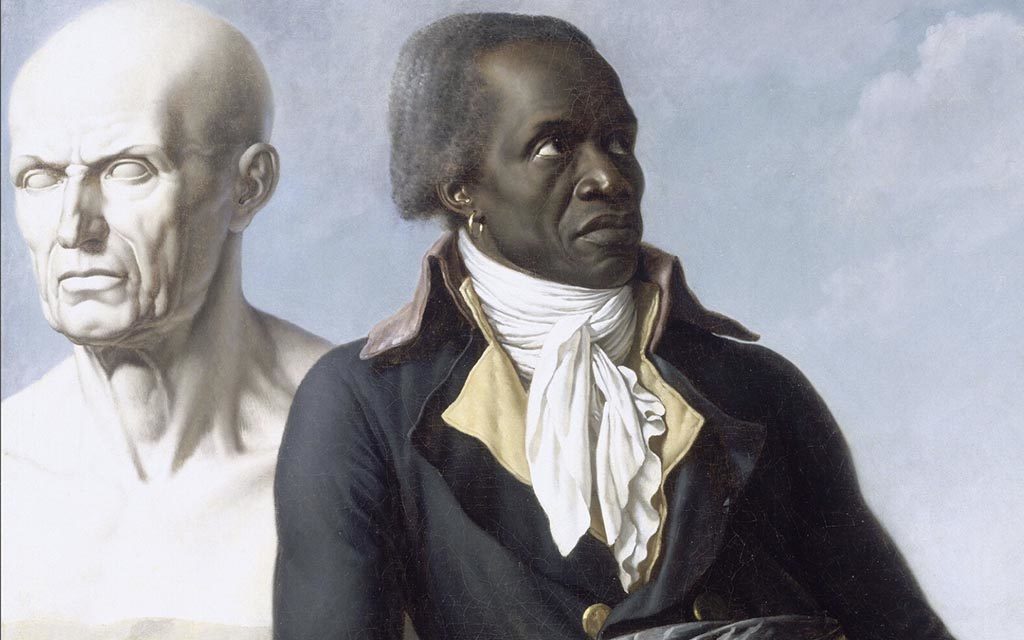

In this painting, Jean-Baptiste Belley is standing, his face slightly turned to his left. On his right lies a sculpted bust of a man. The bust is an homage to the French philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, who actively fought against the slave trade.

Although both men fought toward the same goal, their representation is contrasted. To begin with, Raynal’s figure is oriented toward the left of the painting, thus the past, while Belley is looking up to the right side, toward a better future ahead.

Raynal is represented as an immaculate marble statue, which emphasizes the dark skin of the deputy. Some elements of the image somehow imply that Raynal is somehow greater than Belley both socially and intellectually. This is all the more accentuated by the fact that he is portrayed as a Roman Emperor. Moreover, Raynal’s name is engraved on the sculpture, while the initial title of the painting didn’t even mention Belley’s name.

Jean-Baptiste Belley still remains the main character of the painting. He is in the foreground, leaning nonchalantly on the column supporting the bust. He is represented as a soldier, dressed in an official uniform, holding a hat in his left hand.

As with the tricolor belt, the hat holds a blue, white and red feather to represent the French flag’s colors. It is also acknowledging Belley’s importance to the French Nation. Only his earring reminds us of his past as a slave. Yet, his damaged hands and his white hair entail the things he had to accomplish in order to be equal to any other white free man, such as Raynal.

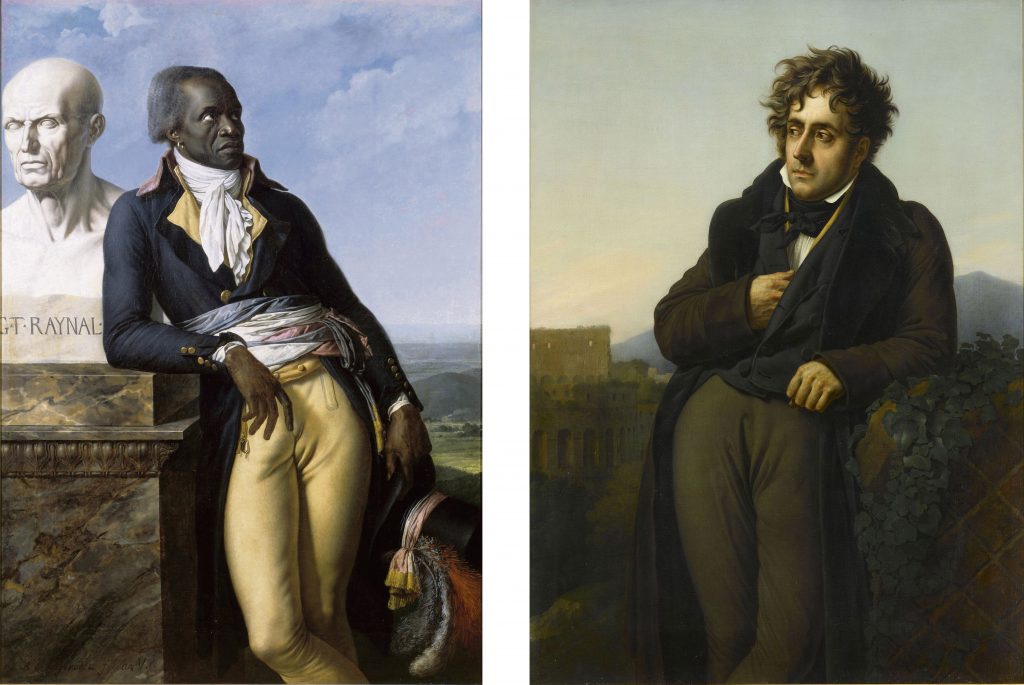

The painting adheres to the conventions of portraiture: the physical representation and the symbolic personality of the character presented against a landscape background. What matters in this genre of painting is who is represented, and for what purpose. Other than that, the compositions vary very little. Or sometimes don’t even vary at all. Ten years after painting The Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, Girodet realized a portrait of French writer Chateaubriand that is almost identical.

Chateaubriand had commissioned his portrait from Girdoet, as is the tradition. Indeed, when a painter realizes the portrait of someone, it is usually on request. Yet, there is not any archival trace of Jean-Baptiste Belley asking Anne-Louis Girodet for his portrait. Moreover, the two men probably never met.

And despite the historical appeal of Belley’s portrait, it cannot be considered a historical painting either. Indeed, the scene depicted echoes neither historical nor personal moments in Belley’s life. The landscape of Saint-Dominque in the background is the only detail partially suggesting the exploits of the soldier. Yet, instead of a battle scene, Girodet painted an exotic, peaceful nature.

All the elements pictured in the painting serve its symbolism. Belley was not a soldier by choice. He did it to access freedom and peace.

Mixing the portraiture and historical genres, Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley is an allegory. Girodet decided to immortalize his time by painting Belley, who symbolizes the abolition of slavery.

Only five years after Girodet’s work was presented to the Salon, Napoleon I reinstated slavery. Despite being a high-ranking soldier, and a legal representative of the French citizen, Belley was arrested. Ruined and isolated, he died in prison in 1805. Despite this tragic end, Jean-Baptiste Belley’s journey is no less important and breaks with an overly idealistic vision of the abolition of slavery.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!