5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Jean-François Millet is the artist who could plow a field all morning, paint in the afternoon, then recite Shakespeare at night. A friend to the working classes and also to the intellectuals of the artists’ colony. A man of contradictions who painted some of the world’s best-known artworks of peasants toiling in rural landscapes. Inspiring artists to this very day, and even changing the law on artists’ rights: say hello to Jean-François Millet.

.

Jean-François Millet, Potato Planters, 1861, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

Firstly, let’s not confuse Jean-François Millet with the British Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais. Our Millet was born in 1814 in Grucy in Normandy, France to a farming family. He lived the life of a rural peasant, and he knew the dignity of the working family. He believed that rural labor was fundamental to life. His father instilled in him a love of nature, showing him the beauty in a blade of grass. After local schooling, Millet studied with the artists Paul Dumouchel and later with Lucien-Théophile Langlois. Studies at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts with Paul Delarouche in Paris ended badly when Delarouche contemptuously called Millet “the wild man of the woods.”

Jean-François Millet, Going To Work, 1863, New Art Gallery Walsall, Walsall, UK.

Millet depicted contemporary social conditions, but this was not the time in French politics to be celebrating the lower classes. The monarchy had been toppled in the 1848 February Revolution. Rebellion and unrest continued and the bourgeoisie did not want to see vulgar, dirty, working bodies in their salons and galleries. But Millet had great respect for the people of his community, and he fervently believed an artist must paint what he knows. He fled a cholera-ravaged Paris in 1849 for a more settled life in the Fontainebleau Forest in Barbizon, Northern France.

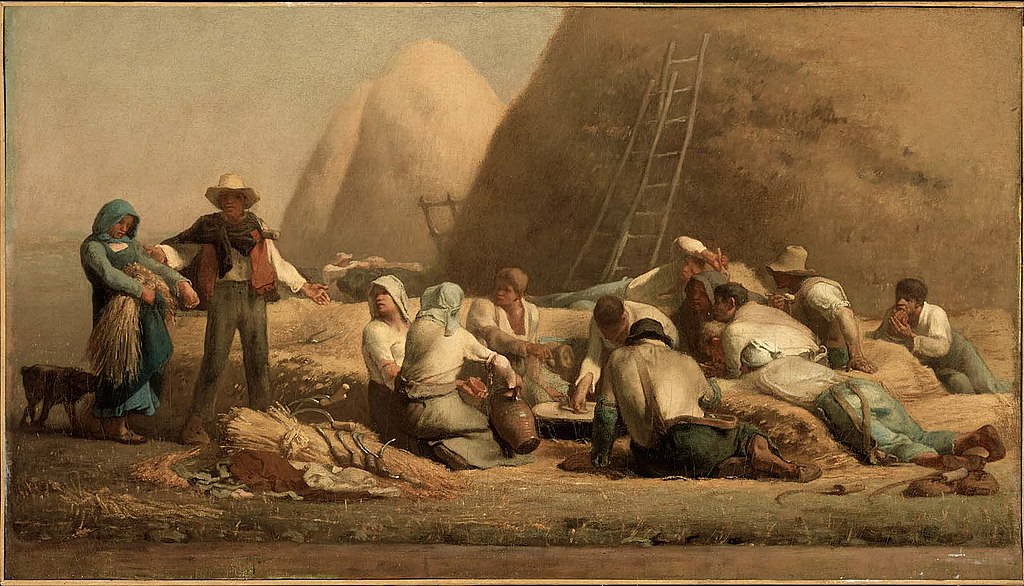

Jean-François Millet, Harvesters Resting, 1851–53, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

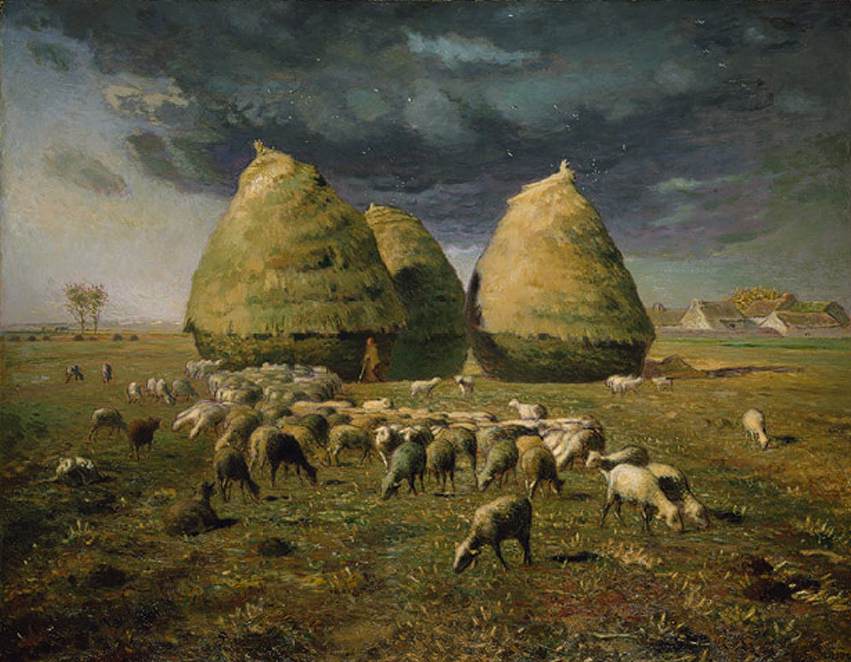

A group of artists gathered in Barbizon, pursuing realist landscape painting, often outdoors. Like his fellow Barbizon school members, Millet knew and loved the landscape. But he also felt the deep urge to include the human figure in his painting. For him the land and the worker of the land were inseparable. The human form is almost always placed in the foreground, but is always dwarfed by the vast landscape.

Jean-François Millet, Shepherd Tending His Flock, c. 1860, Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Millet married Pauline Virginie Ono in 1841, but she died of tuberculosis just three years later. Millet then met Catherine Lemaire, and they had nine children together, who Millet adored. In contrast to his loving home life, Millet struggled for acceptance of the art world and lived in poverty, for a time painting in a moldy, damp cellar. But a handful of friends and patrons helped by buying and publicizing his work.

Jean-François Millet, The Sheepfold, Moonlight, 1856–60, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Theodore Rousseau was one of the first artists to assist and understand his fellow painter. He purchased works by Millet, and they were great friends. Although the Parisian art world still criticized his depictions of genuine rural life, he found American buyers more sympathetic. And even in his native France, by 1867 he was seeing some success and was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1868. Millet struggled with migraines, rheumatism, and sciatica, but he continued to paint throughout his life and died peacefully at home aged 61 in 1875.

Jean-François Millet, The Potato Harvest, 1855, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, USA.

There are common themes throughout Millet’s work. The dignity of manual labor that fed the nation. The fortitude of the field workers, despite back-breaking fatigue. The solemn interaction of landscape and humans. The nobility of the creative human urge to dig, sow, and harvest. His upbringing meant that there was often a spiritual, even Biblical, theme attached to a work. But the central message is the common laborer, an essential part of both life and scripture.

Jean-François Millet, Haystacks, Autumn, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Van Gogh was inspired by Millet, loving his simple rural subject matter. His painting The Potato Eaters of 1885 was directly influenced by Millet’s The Angelus (previously called Prayers for the Potato Crop). It seems both artists loved to paint potatoes! Impressionists Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, and Frederic Bazille all visited the Barbizon School and from there they developed their plein air outdoor painting method. Post-Impressionist Georges Seurat greatly admired Millet’s ability to depict light and Paul Cezanne said that Millet had revolutionized painting by rediscovering nature.

Jean-François Millet, The Angelus, 1857–59, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dali became obsessed with Millet’s The Angelus (shown above). Dali recreated the scene himself, many times (one shown below). And he even wrote a book about Millet called The Tragic Myth of the Angelus of Millet, where he claimed the couple was praying over a tiny coffin. Modern x-rays revealed Dali may have been right!

Walt Whitman commented that his 1855 Leaves of Grass book was Millet’s artwork translated into words—a celebration of nature and the individual within it. Photographer Henri Cartier Bresson studied Millet’s work intensely, looking for inspiration.

Writer and philosopher John Berger felt that Millet told a truth totally without sentimentality. A truth about both the sadness and the dignity of real life.

Salvador Dali, Archeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus, 1934. The Dali Archive.

Millet married Catherine just before his death, to ensure she was legally entitled to inherit. But sadly there wasn’t much to inherit. When The Angelus sold for a half million francs in 1889, it raised awareness that Millet’s family were themselves living in poverty. This led to droit de suite laws (Artists Resale Rights) that allow an artist, or their heirs, to receive part of later resale prices. The work of Jean-François Millet, highlighting the plight of poverty (whether in rural communities or amongst artists) continues to reverberate to this day.

Jean-François Millet, Noonday Rest, 1866, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!