5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

He started out a couch-surfing throwaway. One day, a painting of his would sell for the highest price ever for an American artist at a public auction–over $110 million. He was also a genius. Discover Jean-Michel Basquiat in 5 paintings.

The more that fiscally strapped 1970s New York government retreated from providing city services, the more rebellious its graffiti artists became. They stained the darkened buildings, fettered subways, and gritty streetscapes with loud, accusatory, colorful, illegal, boisterous work. Theirs was the technicolor anger of kids emotionally adrift, coming of age into…what?

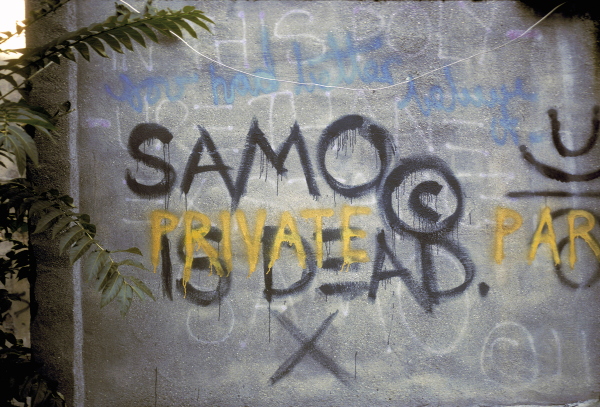

A young, disaffected African-American dropout of Haitian descent created the tag “SAMO©” with his friends and used it to sign his particular spray-paint snark. It meant, “Same Ol’ Shit.”1 Graffiti was texting before texting. His was provoking and barbed, an early sign of the genius within.

Private money would rebuild NYC. Greed made everything glitter. Punk street taggers of the 1970s had opportunities to become collectible artists in the electric 1980s. It would be in graffiti (of course) that “SAMO©” let the world know he was Jean-Michel Basquiat, and that he had crossed over. Fab 5 Freddy Brathwaite, the hip-hop innovator, remembered it this way: “In 1981… [Jean] declared on a SoHo wall that ‘SAMO© is dead’ and began to get very serious about making art.”2

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, “SAMO©” graffiti. Photograph by Martha Cooper, New York, 1982. Art in the Streets.

In the graff game, Jean-Michel Basquait was more author than artist: his street graffiti was monochrome and text-based. When he exploded into art, he brought the best aspects of defacement with him. The simultaneity of palimpsest. The found surfaces. The large formats. The mix of symbols and text. The copyright sign used in the SAMO© tag presupposed today’s hashtag and @ signs. They all declare, “I am relevant!” Like no Western artist before him, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art tells about the American Black man, his central subject.

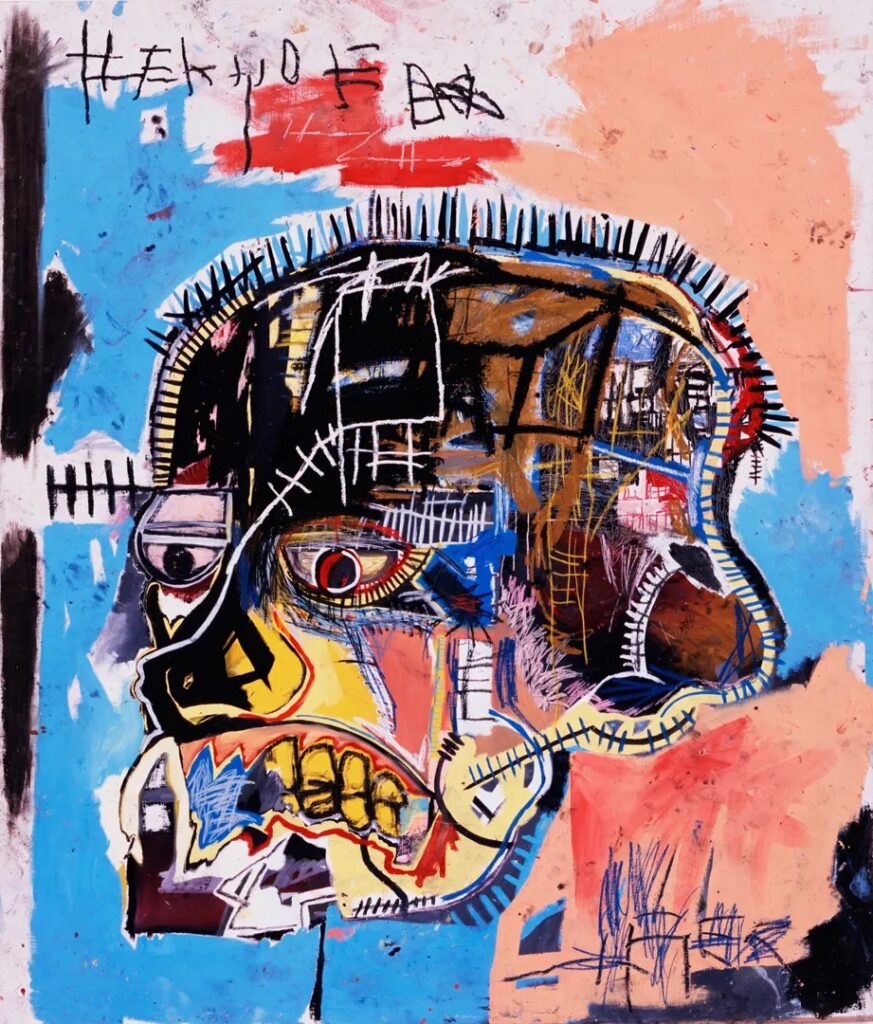

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Skull), 1981, acrylic and oilstick on canvas. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York, Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles. The Broad.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art burned in a cosmology of dualism. Life and death are superimposed in this skull/mask, where black and brown inner rooms may be bustling or empty. Its mouth and eyes bulge as if to speak, but the proto-writing in the upper left and bottom right on the map-like background cannot be comprehended. The skull is the shape of the borough of Brooklyn; the Black man both confronts the city and is of it. The hair is a skyline that becomes surgical stitches, subway tracks, the Canarsie piers, and the Verrazano Narrows bridge. Mining his history against a pure, youthful palette is core to the Basquiat aesthetic.

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Irony of Negro Policeman, 1981, acrylic and oilstick on wood, private collection. Phillips.

Basquiat’s art accused and questioned, but it also hoped. In this work, Jean-Michel Basquiat scratched out his ambivalence about the Black Man as “The Man.” American society continues today to harrow this question—what is the role of Black lives in policing, and of police in Black lives? In yin and yang, a white pair-of-pants shape both overpaints and intersects with the central Black man dressed in blue. But inside the figure, the man’s outline is white. The word “pawn” is in red, and “irony” appears twice.

Basquiat revisited this topic again and again. For example, 1983’s Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), memorializes a young man’s death during an arrest for allegedly marking an L-train with graffiti. The police in the painting are painted bright pink—a skin tone like boiled ham. Stewart is a smaller black shadow with a crooked halo spinning about his head. The title Defacement crowns the painting—it simultaneously references the never-proven crime, the dehumanizing vulnerability of Black men in the gaze of police, and the loss of a young soul from this earth. “It could have been me,”3 he was known to dismay.

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Fallen Angel), 1981, acrylic and oil stick on canvas, private collection. Phillips.

Here is the thing about Jean-Michel Basquiat: He created through destruction. This was both an artistic method (crossing out, defacing, painting over) and a compulsion—he challenged every image with its opposite, destroying boundaries between meanings, exposing hypocrisy, and simply because he experienced the world as contradictions.

Spiritual systems were a natural subject, both because he studied art history and because he was raised Catholic by Caribbean parents in the city of churches. This untitled work depicts an angel with thrown-open white-yellow wings and a broad red mouth. It also has genitalia, being corporeal, not divine. Perhaps this is a mere man on the precipice of choosing a fate. Is he wearing a halo or a crown of thorns? Is his right arm a pitchfork amongst the pinion? Is one foot black and one white? Is the figure floating or falling?

There is a gold crown lurking at arm’s length from the figure’s left. It is both fading and emerging. The crown was an important symbol to Jean-Michel Basquiat. It might mean leadership, heritage, celebrity, ambition. Was Basquait exploring free will in this work? We can spend our mortal time grasping either for the precious metal crown or for our eternal state. This theme repeats in the notebook sketch, Untitled (God/Law) (1981) where judicial scales lay out the Edenic choice.

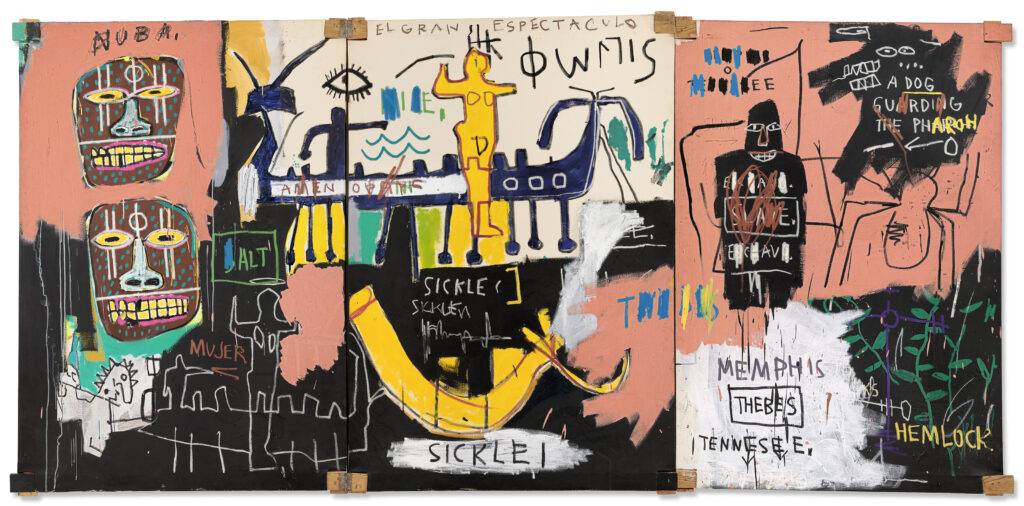

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, El Gran Espectaculo (The Nile), 1983, acrylic and oilstick on canvas, private collection. Christie’s.

Often, simultaneity didn’t hold enough narrative for Jean-Michel Basquiat. He told longer stories in panel form. El Gran Espectaculo is a triptych that is, by and large, a landscape painting, where roughly the bottom half is black water, possibly representing the Red Sea, the Nile, and the Mississippi. Against this is the odyssey of Nuba tribes and people from Egypt, from Africa to the Americas, and an exploration of the dualist tension between bondage and dynasty. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s choice of support is consistent with his telling of an Egyptian narrative since Ancient Egyptian tomb art was also panelized through the use of register lines between scenes.

The story starts joyfully with the face-painting art of Nuba. It moves to a river-boat scene, where the images and word “Sickle” simultaneously refer to the papyrus boats of Egyptian ingenuity, the hand-farming tool of American enslavement, and possibly also the debilitating blood genetics in some African lineage. In the last panel, the river is blotted over with a white landmass inscribed with two river cities of Egypt and Tennessee, USA. These bracket the name Thebes, which itself stands for an ancient Egyptian capital and the Oedipus kingship setting of mythic Greek tragedies.

Many letters are crossed out, one by one, with different marks, making an ominous counting-down of the passage of time and rulers. The last panel features danger—a spider and poison hemlock surround a bound man and a shadowy animal labeled “a dog guarding a pharaoh.”

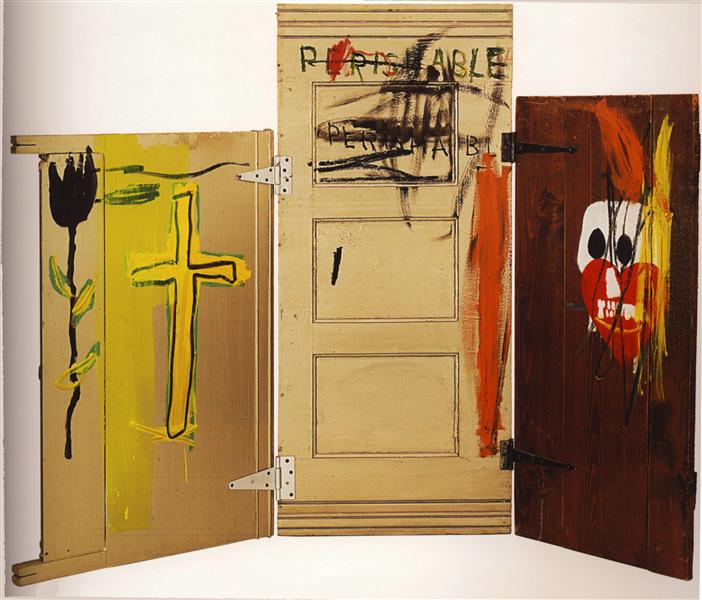

Basquiat in 5 Paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gravestone, 1987, private collection. WikiArt.

Andy Warhol became acquainted with Jean-Michel Basquiat through “SAMO©,” when Basquiat was selling hand-painted T-shirts and postcards on the street. They met formally in 1982. Afterward, the pop artist befriended and mentored him in the commercial art world. Warhol’s untimely death five years later was a blow to the younger disrupter. Consumed by grief, Jean-Michel Basquiat again reinvented the artist triptych, now a self-supporting monument made of discarded but rescued doors. These found objects became a “canvas” for his painting. He tolled the word “perishable” on the center door, then crossed it out. Is death a doorway, or do we perish? The work seems to ask. Unfortunately, later that year, Basquiat would learn the answer.

Just 27 years old in 1987, the millionaire/street kid/genius/disrupter was found in the loft he rented from Andy Warhol, dead of a mixed-drug overdose. Perhaps Jean-Michel Basquiat would consider it wry that, with other lost members of “the 27 Club”—Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Amy Winehouse—he was later commemorated by John Kiss in a graffiti mural. “Same Ol’ Shit,” he might have said.

His colleague, innovator, and former 1970s street artist, Fab 5 Freddy Brathwaite, remembered him in 1988:

Jean-Michel lived like a flame. He burned really bright. Then the fire went out. But the embers are still hot.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jean-Louis Prat, Richard Marshall, Galerie Enrico Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1996, Galerie Enrico Navarra.

That heat is a prolific backlog of artwork, from which we can’t look away, because of the hard questions asked in Basquiat’s extraordinary and hopeful style.

Ingrid Sischy: “Jean-Michel as told by Fred Brathwaite a.k.a. Fab 5 Freddy”, Interview Magazine, October 1992, Excerpt from StanPeskett.com, Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Fab 5 Freddy: Jean-Michel Basquiat – RIP, Art in the. Street. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Dream McClinton: “Defacement: The Tragic Story of Basquiat’s Most Personal Painting,” The Guardian. June 28, 2019. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!