Summary

- How can one explain Vincent’s posthumous fame? He owes it all to a woman named Jo van Gogh-Bonger. This is how it all happened…

This is a story of several moving parts, several plots, and several characters intertwining. It is a story about Vincent van Gogh, yes, but it is more. It is about the power of creativity and art to move and heal the human spirit. It is about learning to see, about learning to find beauty where others would see only imperfection. It is a story about what a single person can do when they refuse to give up.

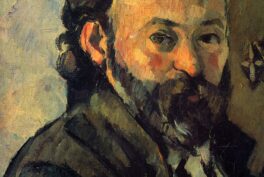

The Painter

Only known photographic portrait of Vincent van Gogh, aged 19, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s website.

Vincent van Gogh was the second-born child in a household that would eventually include six children. He became the namesake of a stillborn son his parents had lost just a year prior to his own birth in 1853. The surviving accounts reveal a young man with a great zest for life, but also a difficult personality, which made it hard for him to keep friends for very long. His family became his source of support and strength.

Vincent was many things throughout his life. He was an apprentice art dealer, a jilted lover, an English teacher, a preacher, a theology student, a missionary… It was not until he was almost 30 that he began to seriously pursue art. He wrote in a letter to his brother:

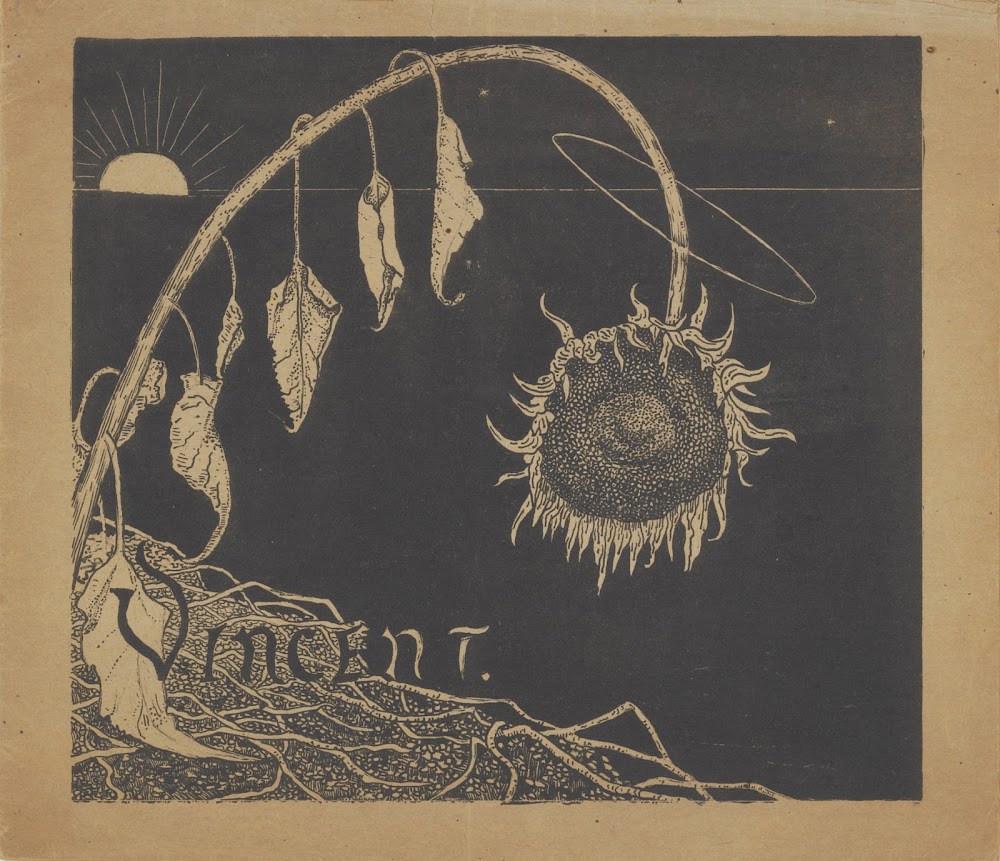

I want to give the wretched a brotherly message. When I sign “Vincent” it is as one of them.

At this point, Vincent was penniless and struggling through a crisis of faith, which must have been deeply distressing for the son of a preacher who had entertained hopes of becoming a preacher himself. However, Vincent had something that a lot of struggling artists do not have.

Vincent had Theo.

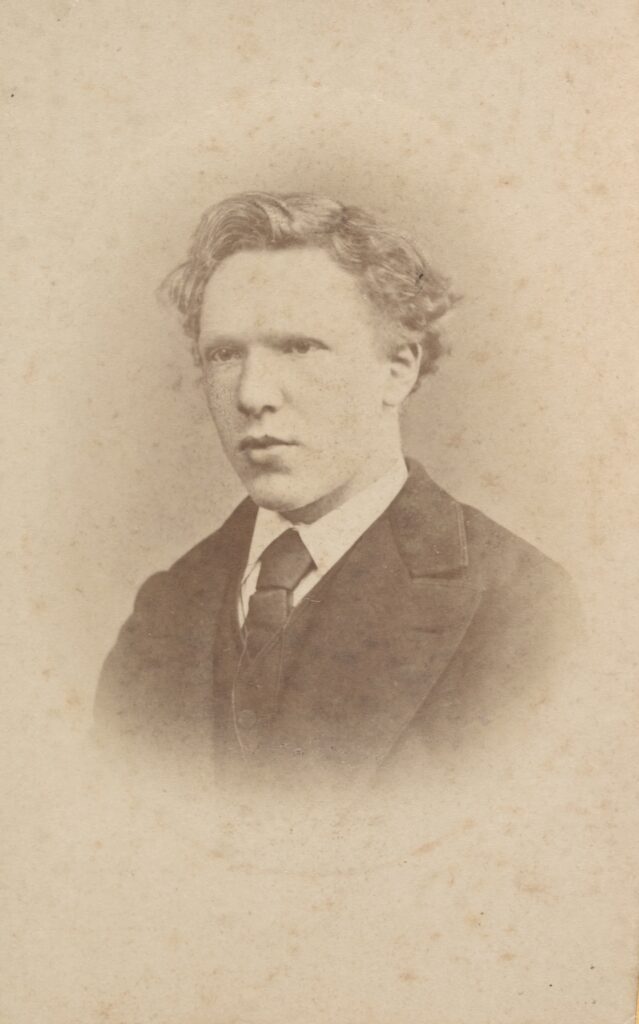

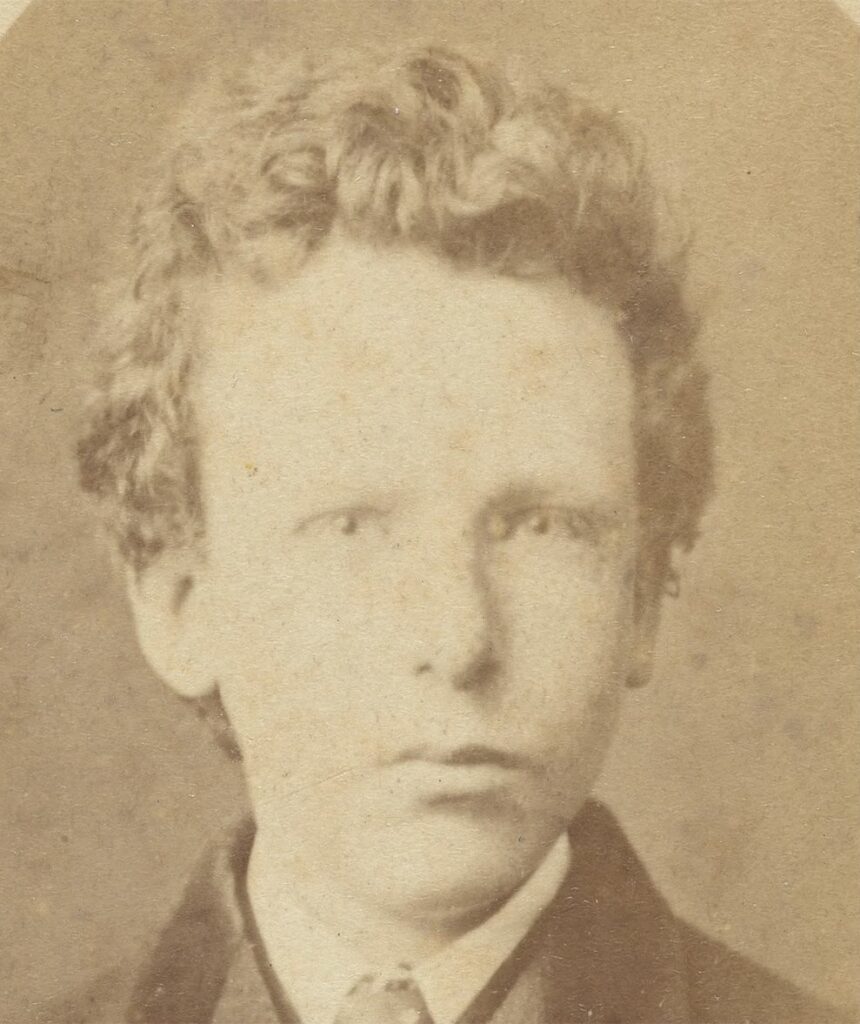

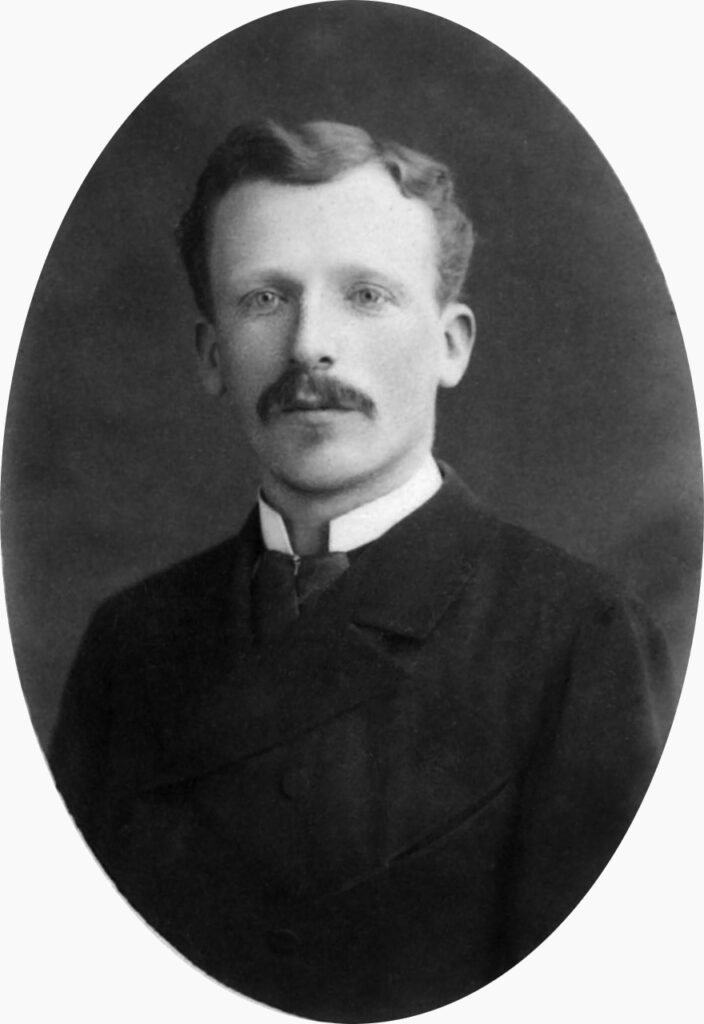

The Painter’s Brother

Theo van Gogh, aged 15, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Photograph by B. Schwarz.

Theo van Gogh was the third oldest surviving child in the Van Gogh family, as well as Vincent’s closest friend and confidante. Theo absolutely idolized his older brother, maybe in part because their temperaments seemed to have been quite dissimilar. Surviving descriptions of Vincent give us a vibrant personality with an impulsive streak. Theo, instead, was soulful, conscientious, and steady.

When he was only 16 years old, he became the youngest employee for art dealers Goupil & Cie. His bosses must have liked his work because they transferred him to the London office, then to the office at Le Hague. By the time he was 27, Theo took charge of the main office in Paris. Through his work, he was instrumental in introducing Dutch art to the rest of the European public. He tried to do the same for his brother’s work, without success. However, when he failed to sell Vincent’s paintings or to help them garner appreciation amongst art critics, he supported him in every other way. Theo sent money, art supplies, and arranged for Vincent’s housing… Vincent did not keep Theo’s letters, though Theo kept every letter he received from his brother—all 651 letters in total.

Perhaps the most important thing that happened to Theo in Paris is that he met Andries Bonger, a fellow Dutch, an employee in a trading firm, the librarian of the Hollandsche Club, and the brother of Johanna Bonger.

The Protagonist

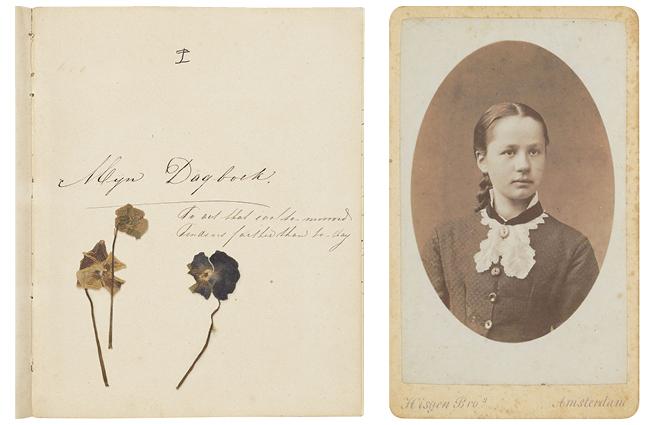

Jo Bonger Diary n.1, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Doppiozero.

Johanna Bonger, Jo to her friends, Net to her family, was a steady, smart, practical girl. She was the fifth of ten children and, by all accounts, she was cheerful, committed, and tender. Her parents could send her to school, though they could not afford the expense of university education. So, Jo learned to play the piano, and entered a Girl’s High School in Amsterdam, continuing her training in Haarlem, where she became an English teacher. For a short while, she worked as a translator in London and then went on to work at a Girls’ Academy back home.

From her diaries, we learn that Jo was also an idealist, not afraid to work for what she wanted. She speaks of “all my ambitious dreams, all my illusions of being and doing something in the world…” She was very upright and even rejected a marriage proposal because she could not bring herself to love her suitor, calmly waiting to see what the future would bring.

The Story Proper Begins

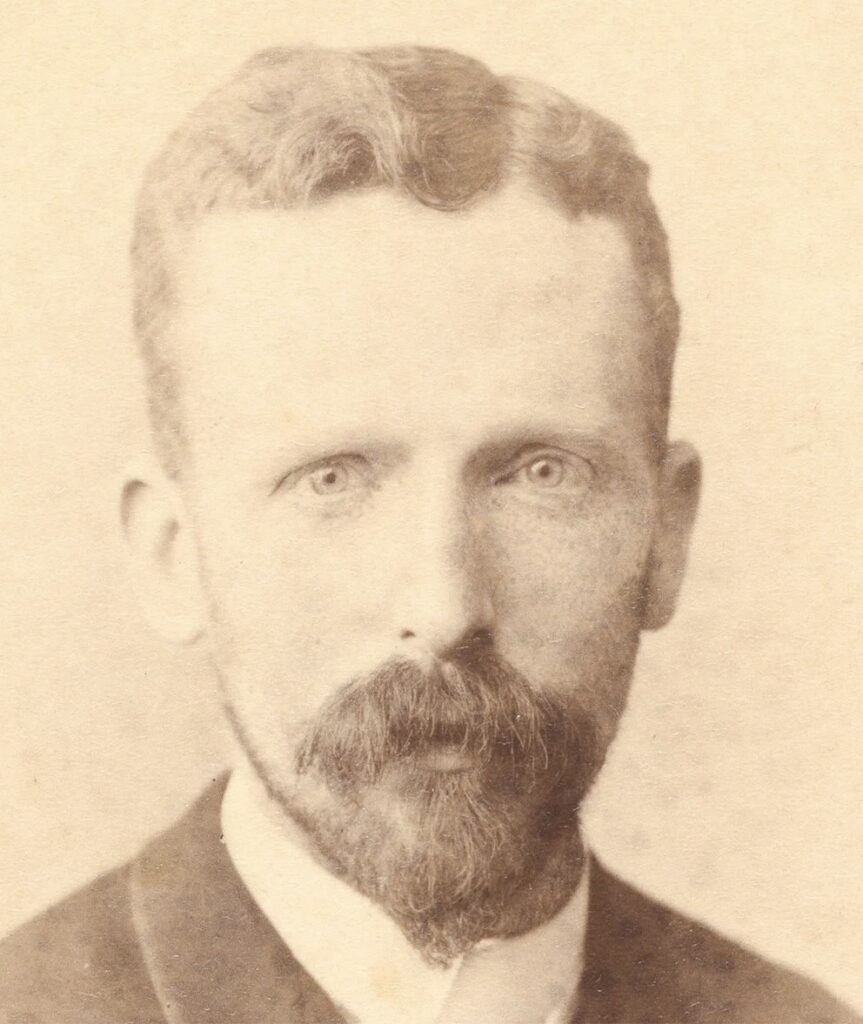

Andries Bonger in his house, c. 1908, Dutch private collection. Van Gogh Museum. Detail.

It was through her brother, Andries, that Jo met Theo van Gogh, in July of 1885.

Andries wrote to his family about Theo. In the letter, he mentioned his membership at the Hollandsche Club and his disappointment that most members:

…fritter away their time without a thought in their heads… With the exception of Mr. Van Gogh, a preacher’s son from Dordrecht. —He is cultivated and amusing. In fact, it was thanks to him that I became a member…

Andries had urged Theo to visit him in Amsterdam, and we have Theo’s reply to that request:

It will for the present give me very great pleasure that we shall have got to know one another’s families, methinks that such a visit will have the same importance for us as e.g. two painters who come to visit one another’s studios, for if the world is the greatest school, family life as we have known it since we were children was the a.b.c. for it.

The Meeting

Pierre Cuypers, Rijksmuseum, c. 1895, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The meeting came about and, for a couple of days, the friends visited together at the Bongers’ home, took rides, and visited the Rijksmuseum, which had just opened. Jo loved her brother very much, the one who came immediately before her in age, and missed him dearly when he was away. Of this visit, she wrote:

And on Friday evening we met Van Gogh and on Saturday the three of us saw the Museum again. How I enjoyed the paintings! And now gone, gone, and everything in me is cold and lonely and in my thoughts I follow them to Paris. Oh, why couldn’t I go too?

Jo may have been thinking of her brother when she wrote those lines, but Theo had other things on his mind. He urged his sister, Lies, to make Jo’s acquaintance because he had fallen hopelessly in love with her.

Theo Makes His Case

Theo van Gogh, 1888. Photo by Materialscientist via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

For a year, Theo worked and waited and hoped for the opportunity to return to Jo in Amsterdam. We have Jo’s record of this meeting when it finally happened:

“Friday was a day full of emotions. At two o’clock in the afternoon the doorbell rang: it was Van Gogh from Paris. I was pleased that he had come, I saw myself talking to him about art and literature. I received him very amicably – and then he suddenly started to make me a declaration. It would sound improbable in a novel – yet it really happened; after being in my company for 3 days at most, he wants to spend his whole life with me, he wants to put all his happiness in my hands. How can it be? And I’m desperately sorry that I had to cause him distress. For the whole year he’s been longing to come here, and he had high hopes, and now this is how it ends.”

In her journal entry, Jo seems genuinely confused about her own feelings and upset that she had to cause him any pain but unwilling to enter into such a commitment with a person she barely knew, and who barely knew her.

“What he conjured up for me was the ideal that I’ve always dreamed of; a rich life full of variety, full of food for the mind, a circle of people around us who wish us well, who want to do something in the world, my vague searching and longing changed into an obligation that’s ready and waiting for me: to make him happy! Oh, if only I could…”

Waiting and Waiting…

Jo Bonger, at about 21. The New York Times.

Theo returned to Paris following Jo’s refusal, but he did not give up right away. He wrote to her as soon as he got home. He mentioned that they had points of mutual sympathy and, curiously, he told her at length about his brother Vincent and the close bond between them. Around this time, Vincent moved to Paris to live with Theo. Vincent was such a force that, pretty soon, Theo had absorbed much of his habits, adopting the “bohemian lifestyle” that Andries so disapproved of and their friendship cooled down.

For her part, Jo developed unrequited feelings for somebody else entirely, in a relationship that never progressed, and that she herself had never been truly sure of to start. This uncertainty about the direction her life should take plunged her into melancholy and, for many months, she even suffered ill health as a consequence. Meanwhile, Andries had married, but his married life had turned out to be very different from all his hopes.

It was to cheer up her brother and to give herself a change of scenery, that Jo traveled to Paris at the end of 1888.

A Reunion

Theo van Gogh, aged 32, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Van Gogh Museum.

When Jo realized that Andries and Theo had not seen each other in almost a year, she decided to do what she could to help them mend their friendship. Theo wrote to his mother that he had bumped into Jo Bonger:

We chatted to one another & she asked if she could speak to me. She first wanted to know whether it was her fault that I no longer socialized with André. One subject led to another and we were on such informal terms I thought I could treat her amicably, and I became good friends with her & her brother once again.

In a letter that Theo sent to his sister, he wrote:

“She [Jo] had been staying at her brother’s for about a month when I met her, & was in fact just about to leave. We saw one another more than once & I soon realized that I still loved her just as much as before. We understood one another better this time & I do not think that this past year with all its love & sorrow has been bad for us at all. She is a noble, sweet girl in whom I have the greatest trust. Can I make her happy like she expects me to? I shall do my level best.”

Brief Happiness*

Jo van Gogh-Bonger with her son Vincent Willem, 1890. Photo by Binho24 via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Jo and Theo were together for just about two years. They got married in 1889 and left for Paris. Jo wrote to her sister enthusiastically about her new life:

Theo is so kind and good to me – and we are getting on so well together, we were used to each other from the very first moment, nothing forced – nothing strange – he is so simple and natural, that makes it so easy and he says the same: I didn’t think it would be so good.

Jo absorbed her first lessons in becoming an art dealer from Theo himself. What makes art? And, what makes art beautiful? She must have thought about these questions as she helped her husband do his work at the gallery and cared for their son, Vincent Willem. She sensed that Theo was in the middle of something new, supporting new artists, and helping the world wake up to a different kind of beauty, a kind they had not yet seen and that they did not know they were going to like.

But it was not to last.

* Brief Happiness is the title of the compilation of the letters exchanged between Theo and Jo from 1888 through to shortly before Theo’s death in 1891.

The End?

Graves of Vincent and Theo van Gogh at Auvers-sur-Oise Cemetery, Auvers-sur-Oise, France. Photo by Ellebel, via FindaGrave.

Vincent died in Auvers-sur-Oise in July of 1890 and Theo managed to arrive just in time to see him pass. It was a terrible season for them both and Theo never fully recovered. Jo’s letter to Theo on the event of Vincent’s death is poignant in its grief and her worry over her husband:

I am so sad, so profoundly sad, and I can’t even put my arms around you and share in your grief. If only I had stayed there so I could at least be with you in these sad hours of your life . . .

All I want is to be with you now, to put my arms around you and show you how much I share in your grief and how dearly I love you. Goodbye, my dearest love, my thoughts are always with you—

However, by the end of the following January 1891, Theo was also dead, leaving Jo a son, and an apartment full to the brim with Vincent’s work — work that nobody wanted, that same work that Theo had failed to show and to sell. And there was so much of it: over 400 paintings and several hundred drawings.

A New Beginning

Villa Helma, the guesthouse that Jo opened in Bussum, Netherlands. Van Gogh Museum.

After Theo’s death, Jo returned to the Netherlands where she opened a boarding house to support herself and little Vincent. Once there, she began to ponder what to do with the legacy Theo had left her, his mission to put Vincent’s art out into the world.

Records tell us that she spent months trying to decide where to hang all of Vincent’s paintings. She hung The Potato Eaters above the fireplace. In her own room, she kept three renditions of Orchards in Blossom. These were her companions as she thought, wrote, read, and tried to decide what to do next. From Theo, she had learned the beginnings of an art education but she recognized that she now needed knowledge of art criticism. Only then could she figure out how to present Vincent’s work in a way that people would appreciate it.

With the same zeal she showed in everything else, she began to read art journals, books on criticism, biographies… Also, in what became a turning point for her, she began to read from the stash of Vincent’s letters that Theo had saved—all 651 of them.

The Key to the Puzzle

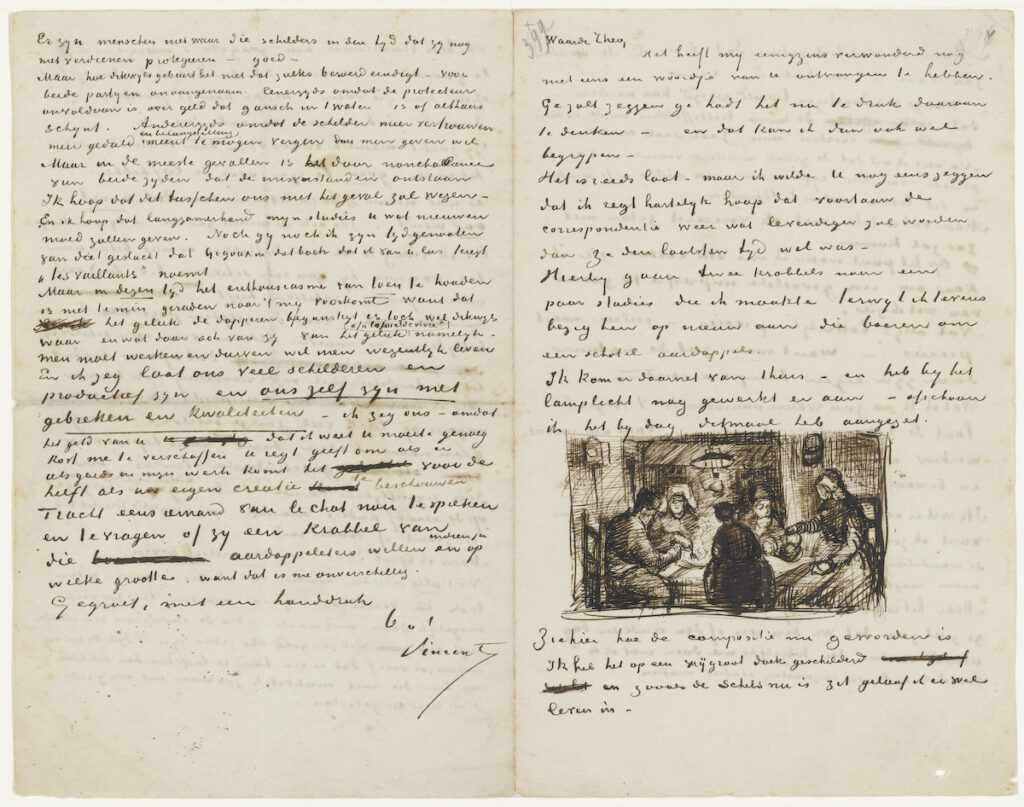

A letter from Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, Thursday, 9 April 1885. Photo by P. S. Burton via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Vincent’s letters were full of life and full of details. He wrote about the intense colors that surrounded him everywhere and that he sought to recreate in his paintings. He wrote about techniques he experimented with, about his inspirations and about what he was trying to say with each work of art he began.

Jo read on, fascinated, moved by her brother-in-law’s words. She felt so close to him, for the first time understanding what he must have felt, almost living what he must have lived. It was then that something extraordinary happened. Jo could finally see what everybody else had missed before; the key to appreciating—to understanding—Vincent’s art was in the letters. One could not simply look at the paintings and understand all the depth of feeling that lay behind them. Paintings and letters both had to go together. It was the letters, in the knowledge of the intense, tragic, and beautiful life that originated the paintings, that would illuminate their beauty and meaning.

This was a momentous step in the story of art and one for which we must all be grateful. Until this point, the art that was shown at the salons and galleries, the art that people commissioned and bought, had a purpose only outside of the artist’s own life. Artists did not paint or sketch or sculpted to show their inner world. The measures by which a viewer could judge the merits of a work of art were mostly based on the painters’ technical skills.

That was all about to change. Now that Jo understood this, she could finally see the way forward.

Step by Step

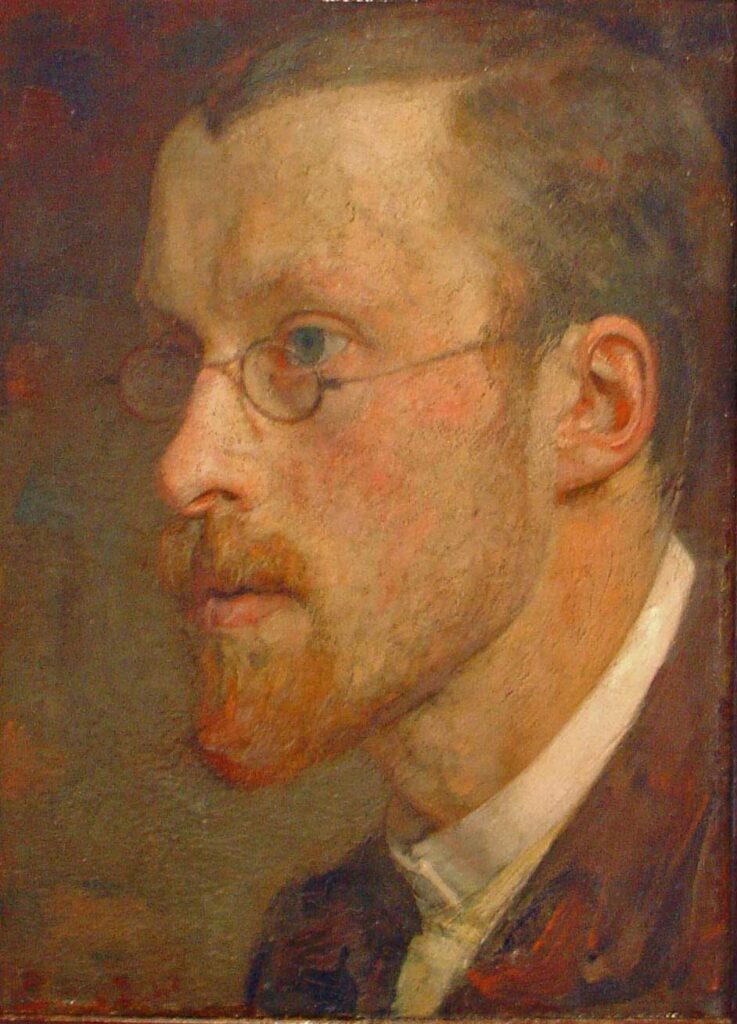

Jan Veth, Self-portrait, 19th century, Drents Museum, Assen, Drenthe, Netherlands. Photo by Gouwenaar via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Her first step was to enlist the help of art critic Jan Veth, who was a friend, and who believed that individual expression in art was more important than following academic guidelines. It took some work to convince Veth to even take a good look at the paintings. He could not see the value of the work and he was not very keen to let a woman with no experience tell him what made good art.

But, Jo persisted. She decided she would not rest until Veth liked the paintings. So, instead of pestering or annoying, she simply brought him the letters and asked him to read them.

Needless to say, Veth was reluctant. Why did one need to know about a person’s life to appreciate their art? That was not how art criticism was done. Jo kept on urging him, however; telling him that at first, she had read the letters because they brought her closer to her dear husband, Theo. After a while, she had begun to understand Vincent himself—what had moved him, what had inspired him, what had prompted his work. This connection had so profoundly changed her that she had found serenity. All she asked of him is to give it a try, as she had.

With such a plea to encourage him, Jan Veth took the letters and, half-heartedly, read them.

Nobody could have imagined what would happen next.

A Change Begins

Catalogue of the Van Gogh exhibition in the Kunstzaal Panorama Amsterdam, December 1892. Van Gogh Museum.

Veth wrote one of the first appreciations of Vincent van Gogh’s work, declaring that he could now understand that what Vincent had been seeking was the raw roots of things, to see the world exactly as it was, portraying it and everything within it in its full, imperfect beauty.

After Veth’s favorable criticism, many more followed. Soon, Jo was showing Vincent’s work in galleries. People were wanting to buy it all over Europe. She sent Vincent’s paintings to over 100 shows and learned, by doing, the best ways to encourage people to buy art. For example, she would send works on loan, hanging them next to works on sale at any given show. This increased their appeal because viewers (and potential customers) knew they were there, yet could not buy them. Or, she would send many works but stipulate that a quarter of them were not for sale, to increase their value in people’s eyes.

Jo did this for a while as she learned and watched what worked, and observed people’s reactions to what she was showing them. It was now time for Jo’s big statement.

The Test

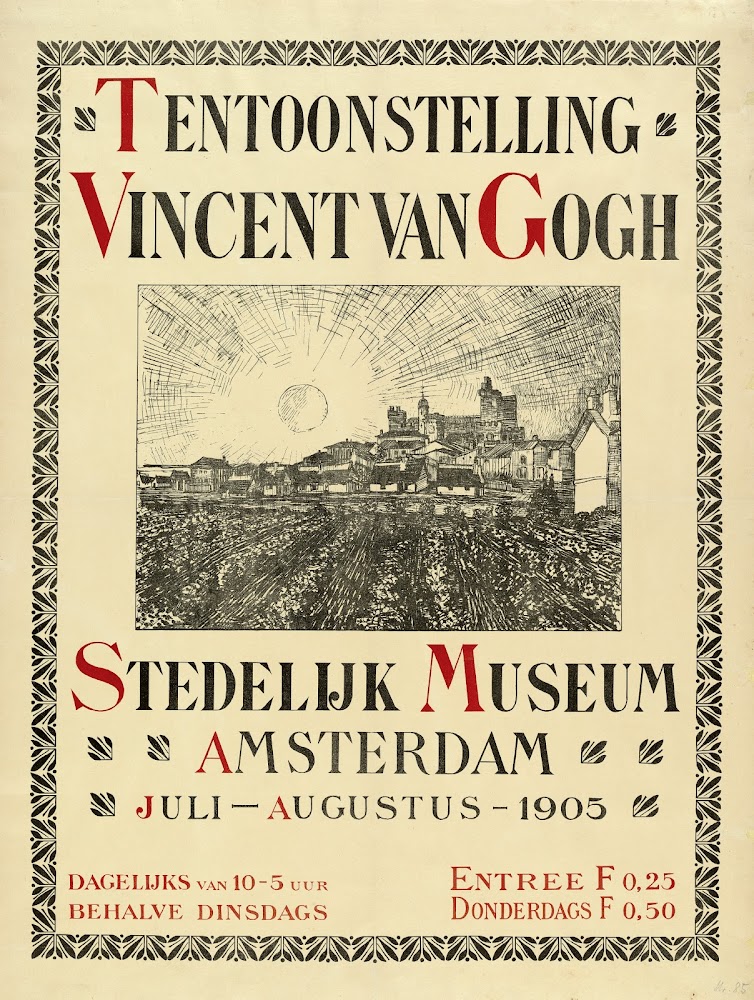

Poster of the Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, 1905, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam,Netherlands. Van Gogh Museum.

15 years after Vincent van Gogh’s death, Jo van Gogh-Bonger organized the largest-ever exhibition on the work of the artist, with 484 works on display, at the Stedelijk Museum—Amsterdam’s biggest showcase of modern art. She insisted on doing everything herself. She rented the galleries, organized the space, decided what works would be on display, and where they would be hung, printed posters and made lists of important people to invite. Little Vincent, now 15 years old, wrote the invitations. The question was—would people come?

Oh, yes. People came.

People came from all over Europe. After this exhibition, the prices for Vincent’s paintings started to rise two to three times in the following months. A while later, everybody felt like they knew Vincent intimately, and his struggle to bring beauty and meaning to the world.

A Legacy

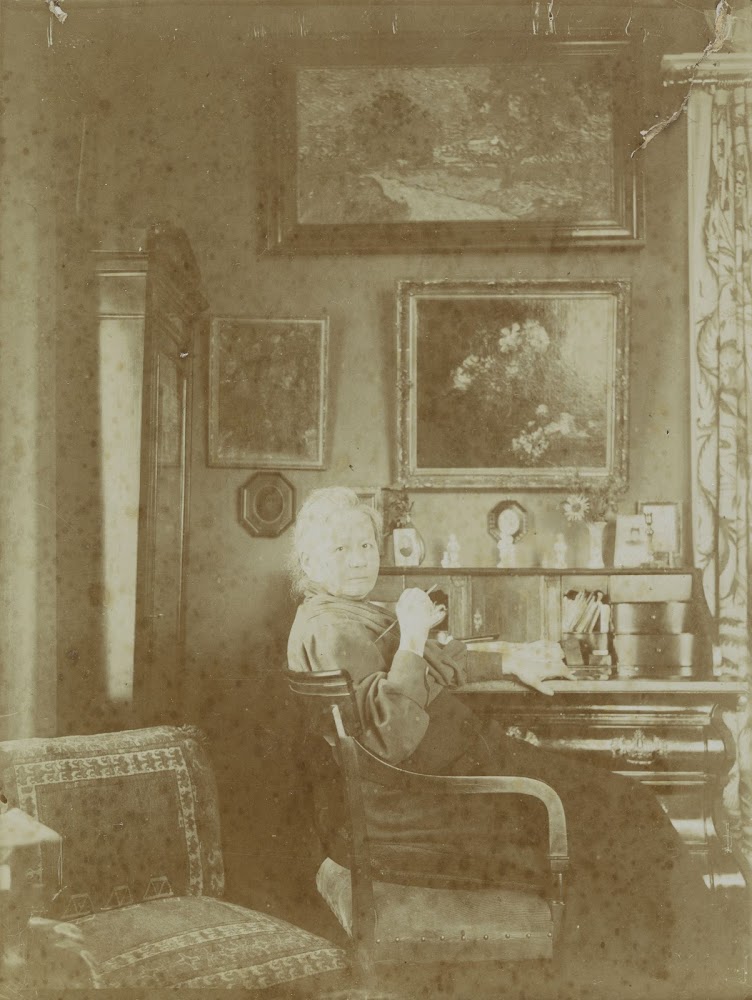

Jo van Gogh-Bonger in the living room of the house on the Koninginneweg 77, Amsterdam, 1914-1915. Van Gogh Museum.

Jo worked tirelessly throughout her life to uphold the Van Gogh legacy. Once Vincent was well-known in Europe, she took it upon herself to make him known throughout the whole world. So, she moved to New York for a while, bringing her letters with her. The last great task of her life was to have the letters translated into English and to prepare them for publication.

Little Vincent grew up to become an engineer. After Jo’s death, as custodian of all the art that his father and uncle had left him, he founded the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where all of the art that Jo couldn’t bear to part with is on display for everyone to see and enjoy, just like Vincent and Theo had wanted. The family still helped build upon what Jo started in that small room in Bussum, as she read Vincent’s letters.

And art?

Art was changed forever by an intense painter and his devoted brother, and the brother’s determined wife. Without Jo, there would be no Vincent. And without Vincent, the world would have been so much poorer.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger with her son and second husband, Johan Cohen Gosschalk. Photo by Thomon via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).