Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Her career lasted barely 20 years but Joan Eardley (1921–1963) left behind a huge cache of monumental seascapes and poignant portraits which are loved across Scotland. But why isn’t this passionate and prolific artist more well known across the world? Despite her short career, Eardley produced thousands of sketches, pastels, and oil paintings. Let’s take a look at this prolific painter.

There are those who may look at her tender portraits of children with a sentimental eye. Ah, the poor wee kids, in their mismatched clothes and grimy faces – how sweet! I suspect Eardley would have no truck with that. She painted what she saw, without sentimentality. She painted with respect and genuine affection.

The reality of life for the working classes can be savage and chaotic. But also vital and energetic. And Eardley somehow managed to capture that. How we represent deprivation matters – in art, in literature, in the media. Eardley’s children are a far cry from the nostalgic and maudlin depictions of the poor by the Romantics or the Victorians – all angelic faces and torn gowns. These children are real and gritty, and Eardley lived alongside them. She was neither tourist nor voyeur.

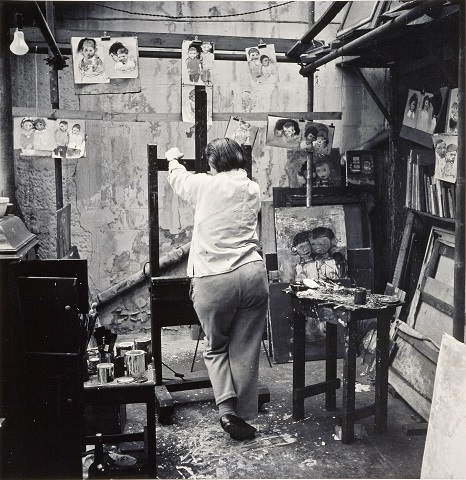

There are artists who tour the grimy cityscapes, looking for “authentic” poverty to photograph and paint. The Poverty Safari and the structural inequality that produces poverty has been eloquently written about by Scottish writer and rapper Darren McGarvey, aka Loki. But Eardley lived in the heart of the city of Glasgow, in a crumbling tenement block. Her studio was a small room packed with her art materials and a narrow bed. Everything she needed or wanted was right there.

For Eardley a truly successful painting had to go deeper than a mere visual record, no matter how accurate… Her success lay in her ability to combine the acute, uncompromising painter’s eye with a warm human sympathy and understanding.

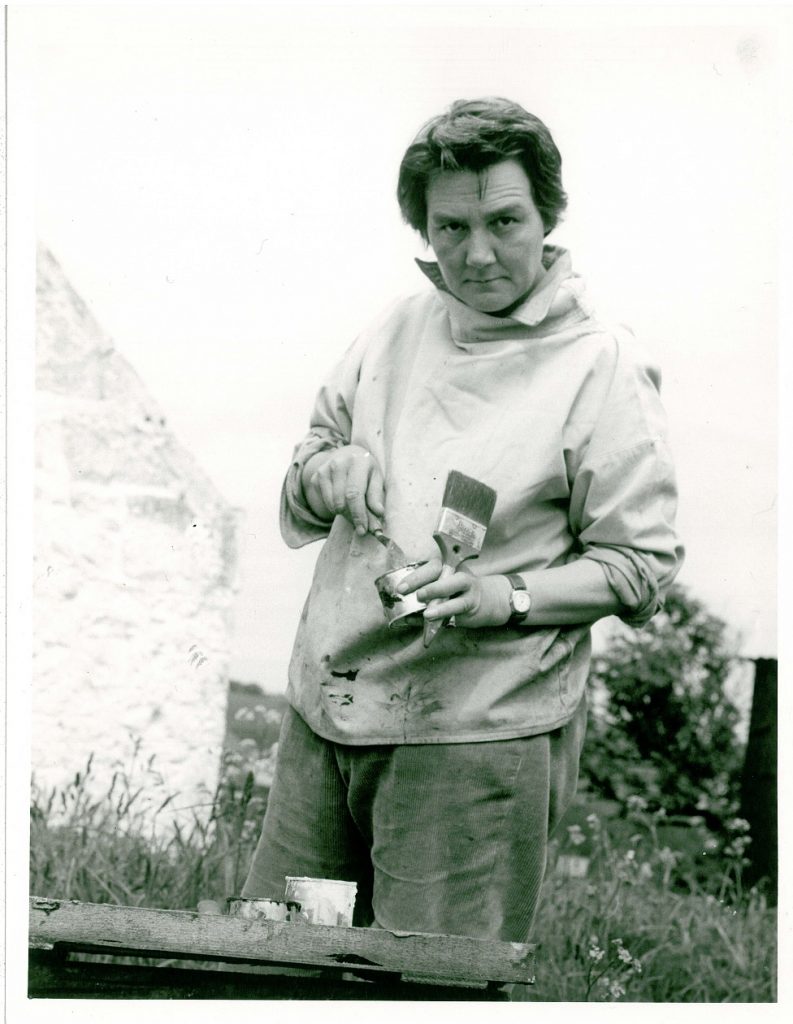

Artist Cordelia Oliver.

Often referred to as “painfully shy” (which is true) Eardley nevertheless maintained deep friendships and passionate relationships throughout her life. Although she lived in a time when being a lesbian was unacceptable to the majority of the society, she was unapologetic about her sexuality. She was self-aware and unashamed. However, she did live with depression for most of her life. Her father William Eardley returned from World War I traumatized by what he had seen. He never recovered and killed himself when she was just 8 years old, though the truth was hidden from the Eardley children until they were adults.

Joan Eardley’s closest friends included Margot Sandeman, Audrey Walker, Cordelia Oliver, Bet Low, Angus Neil, Lil Neilson and Dorothy Steel. All were accomplished artists. Audrey Walker documented lots of Eardley’s work and the places she painted with amazing photography. Josef Herman was another fellow student from Glasgow School of Art.

Joan Eardley was born on a dairy farm in Suffolk, England, in 1921, but her mother moved the family to London at an early age. Eardley grew up in a strong all-female household – her mother Irene, sister Pat, grandmother Ellen, and aunt Sybil. In fact, aunt Sybil was a well-known suffragist, who fought for women’s rights.

When the war came in 1939, the family evacuated to Scotland, and Eardley joined the Glasgow School of Art in 1940. A wartime-enforced reduced student intake made for a close-knit group of students, mainly women, who founded life-long relationships and support networks. Eardley’s talent was recognized early on, and she won traveling scholarships which allowed her to visit both Italy and France.

In 1942, Eardley visited the village of Corrie on the isle of Arran for the first time and fell in love with the landscape. Taken there by friend Margot Sandeman, she met islanders and sketched them – especially Jeanie Kelso, who fed her hearty soup and bread. Eardley later traveled northeast, up into the wilds of Aberdeenshire with her friend Annette Soper. Here she found Catterline, on the far northeast coast of Scotland. From that moment, she shared her time between Glasgow and Catterline. Wearing a wartime flying suit, old coat and huge boots, she would lug her materials around with her in an old pram, or tied to her little moped, moving between the two communities that would inspire and entrance her for the rest of her life.

Catterline was a working fishing village, where the tide times ruled the day. Eardley lived in a tiny cottage with a leaking roof, a dirt floor and no plumbing. She worked outside, loving the rough wind and rain most of all. Two years working as an apprentice joiner during the war years even taught her how to patch and fix the roof! Her quiet determination, sheer physical strength, and tenacity to be out in all weathers, drew respect from her village neighbors.

The change from the crowded inner city to the desolate and remote coast may seem strange at first, but Eardley found common ground between the two. In both communities, we see resilience in the face of extreme hardship. We see real, full lives being lived out regardless of difficult circumstances. The beauty of every day, the ordinary. Eardley was drawn to the vital life force of the tenement dwellers and the fishing folk. People who are inseparable from their time and place. When asked directly about the difference, Eardley said:

The children seem to be no more aware that I’m painting them than the sea and the cliffs are aware of me.

Interview with Conrad Wilson in The Scotsman (25.05.1963) in: Patrick Elliott, Joan Eardley, A Sense of Place, 2016.

On the coast, Eardley is consumed by the most elemental force of all – the sea! When she first painted in Catterline, Eardley turned her back on the water and painted the landscape: the tiny cottages clinging to the cliffs, the fishermen’s nets drying, the change of seasons across the fields. But in the 1950s she finally turned to the sea. And what a moment that was. Eardley became a storm chaser, her paintings became more abstract, full of power and pounding waves. Now she painted on hard boards – canvas would be taken by the wind like tissue paper. She tied down her easel with blocks, even using an old anchor she found. She faced the seething, roaring, foaming sea as if it were a living, breathing thing, and created its likeness in paint.

If Eardley received a call in Glasgow that a storm was approaching Catterline, she would drag her trusty moped on the train and head for the coast. She added sand, gravel, grasses, and boat paint to her paintings, endlessly experimenting. She would prepare boards with plaster, harshly gouging the surface. A humorous tale describes her sending work to her London gallerist Gustav Delbanco, who was horrified to see this experimentation. In fact, he scraped and picked off the collage effect! Suffice to say, Eardley was not amused.

As well as a treasure trove of incredible art, Eardley also offers us a slice of social history that would otherwise have gone unrecorded. In Glasgow, she chronicled the end of an era. The tenements she painted were soon to be razed to the ground, replaced with tower blocks and a motorway. In Catterline, she saw the end of the fishing industry and the depopulation of working coastal villages. Her creations are astonishing. Tommy Zyw, Scottish Gallery Director, calls it “a realness of place.”

Comparisons between artists are the bread and butter of art history. And Joan Eardley does not escape, although she is in fine company! Her seascapes are compared to Turner; her landscapes are compared with Constable and McTaggert; painting only what she can see brings comparison to Gustav Courbet; the use of graffiti and collage compares her to Basquiat (although she predates him by two decades). All male artists of course. I eagerly await the day when a male artist’s work is described as “like an Eardley.”

A comparison that jars most painfully is when Eardley is described as having a “Ruskin-like gaze.” I cannot think of a more inappropriate or offensive comparison, especially with regard to children. Eardley had an easy and affectionate attitude to the children she painted. She admired their verve and their energy, without wanting anything from them other than to sit still long enough to be sketched. She offered them pennies and sweets and drawing materials while they sat around the heater in her studio. She had a genuine kinship with the communities she painted. John Ruskin, on the other hand, had obsessive and inappropriate relationships with his young female sitters and was a predatory, sentimental man. The two versions of “innocence” presented by these two painters are poles apart.

Trying to shoe-horn Eardley into a pigeon-hole or into an art movement has proved quite thorny. She was not quite a social-realist, not quite an Abstract Expressionist, not part of the English Kitchen Sink school, and not a Scottish Colourist for sure, as her palette of color was often quite limited to the natural earthy tones of the landscape.

Although she often adds a splash of bright color in a key position, confirming her confident eye for balance and vitality. Her Scottish contemporaries included Eduardo Paolozzi, Robert Colquhoun, and Robert MacBryde. These peers from the Glasgow School of Art moved quickly on to London to make names for themselves amongst the art set, but that held no appeal for Eardley. She loved Glasgow and Catterline, and that was enough. She said:

I think you’ve got to know something before you paint it.

Extract from a tape recording in the Joan Eardley Archive, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland: GMA/09.

Although painting was her lifeblood, Eardley was also a voracious reader and loved music. She has been described as a “thinking painter” – her Expressionist style of art was fed by great intelligence and incredibly careful, well-planned use of line and color. Contemporaries spoke of her incredible physical energy and the brutal force with which paint flew from her brush to the canvas.

Joan Eardley died of breast cancer aged just 42 in 1963, at the peak of her artistic powers. We have no idea what she might have done next. Her ashes were scattered on the beach at Catterline.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!