Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

On December 19, 1930, in Muskogee, Oklahoma, Joan Hill was born into an influential family of Creek and Cherokee descent. After dabbling in art during college and some thoughtful advice from a teacher, Joan Hill dove into her ancestry and began creating paintings that communicate her heritage. Today, we delve into her journey of following in her family’s footsteps while carving her own path as one of the most renowned female Native American artists of the 20th century.

Photograph of Joan Hill standing with one of her paintings of a 19th-century Muskogee leader. First American Art Magazine.

From a young age, Hill loved art. In an interview with First American Art Magazine, Hill recounts how some of the earliest art she made was drawn on the walls at home. To keep her from doing this her father bought paint and paper for her. As it would turn out both her parents were artistic. Her father drew quite a bit in school. When it was cold, he would draw figures in the frost on the window or in the dirt when they were outside waiting on someone. Hill’s mother was an artist as well as an accomplished pianist and vocalist. As a child, Hill recalls her mother’s continued love for music. She frequently listened to the opera on Saturday afternoons.

Hill received her education in Muskogee public schools before attending Muskogee Junior College and Northeastern State University. During this time she dabbled in art with Frederick Taubes and Dick West and took classes at the Philbrook Art Center. Hill earned her degree in education and taught in Tulsa public schools from 1952 to 1956. At that point she changed paths, choosing to pursue a career as a painter. She also spent eight years working as a director of the Muskogee Art Guild.

Although most know her as Joan Hill, she also took a name in her ancestral language, Chea-se-Quah. The name means “red bird,” which suits Hill’s use of vibrant colors. The name stems from her maternal grandfather and great-grandfather, Redbird Harris, who was a full brother to the Chief of the Cherokee from 1891–1895 Her paternal grandfather was also Chief of the Creek from from 1992 until his death in 1928. The land her family lived on had been their home for many generations; several of her family members played important roles in establishing and developing the land. One person in the town frequently joked with Hill, saying too many things were named for her family.

Despite her ancestry, Hill was not raised in the traditions of her tribe. When she decided to become a painter, she hadn’t studied the legends or history of the tribes and felt unqualified to be a serious artist. After she quit teaching Hill moved home and enrolled in a portraiture course at Bacone under Dick West. This is when she and West had a conversation that would shape her career. He said: “With your family’s background, it’s a shame that you don’t do Indian painting.”

West encouraged her to research her heritage and that is just what she did. Her father, who was also descended from the Creek and Cherokee, had many connections and took Joan and her mother to many ceremonies. Hill began taking photographs that she later made paintings of. Hill’s father also passed on the legends that his father had shared with him and his grandfather before him. In time, Hill had all the tools she needed.

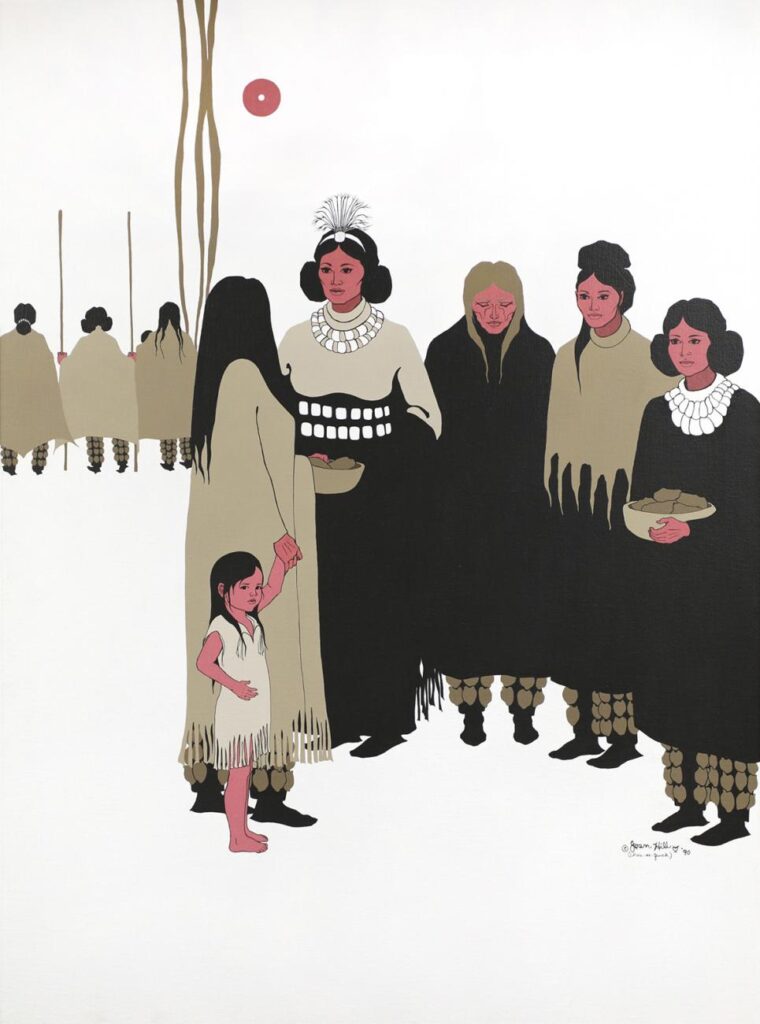

Joan Hill, Women’s Voices at the Council, 1990. Gift of the artist on behalf of the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women, 1990, Oklahoma State Art Collection, courtesy of the Oklahoma Arts Council, Oklahoma City, OK, USA, © Joan Hill.

Throughout her career, Hill experimented with many mediums and styles, ranging from Realism to Expressionism, and Abstract Expressionism. She also combined the traditional Native American two-dimensional style with various contemporary styles. However, she admittedly never had a preferred style; she found unique qualities in precise work as well as the abstract pieces she created.

She experimented with many different techniques and was open to how her work could morph from style to style. In her interview with First American Art Magazine, she states:

They just evolve. Sometimes I start one type of painting and it will turn into another type. Sometimes I start a painting, and I don’t quite know what to do with it. So I don’t bother with it. Two or three months later, I look at it, and then I know what to do. I dream paintings. But when I try to paint what I dream, it doesn’t reach [what I’ve dreamed]. Sometimes it turns out to be a good painting, but it’s hard to reach that.

What never wavered about her work were the themes she found rooted in her ancestry. Women’s Voices at the Council is part of a series she started in 1971 during the Vietnam War. In it, we see several generations of women and their power to decide between war and peace. The flat, graphic style of this painting highlights Hill’s attention to detail in the women’s clothing, like turtle shell leggings, headdresses, and jewelry. She also juxtaposes cultural symbols; the white background stands for peace while the red disk could represent the looming threat of war.

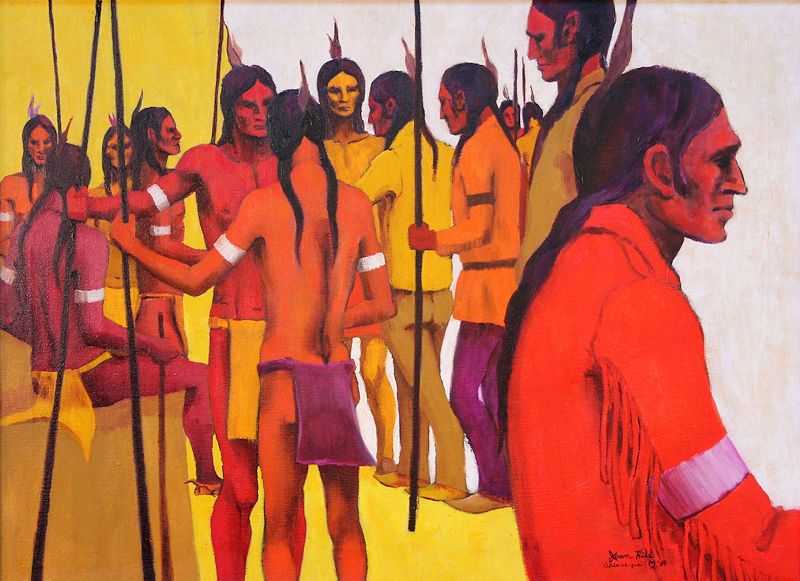

Joan Hill, Creek Ribbon Dance, 1964, Bureau of Indian Affairs Museum Programs, Reston, VA, USA.

In 1959, Hill had her first exhibition at the Philbrook Art Center in Tulsa. She also sold her first painting in the 1950s. Upon receiving a letter from the groundskeeper and the Gilcrease Museum, she opened it and three $5 bills fell out. Hill exclaimed, “Mother, I sold a painting. I sold a painting.” While she didn’t win the first show she entered at the Philbrook, the painting also sold for $100, which was a lot of money to Hill at the time.

As she continued entering various shows, she gained even more traction. Hill became the first female Native American artist to attract serious attention from art collectors and museums around the world. Her work began fetching prices upwards of $3,000. Years later, a cultural art specialist with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington valued one of her paintings at $20,000.

High prices were not Hill’s only marker of success. She was frequently sought out for various teaching opportunities. Hill’s teacher, Mr. West, spoke highly of Hill’s artistry and teaching to Lloyd Kiva New, founder of the Institute of American Indian Art. Mr. New traveled to New Mexico to offer Hill a job teaching classes in experimental painting but Hill declined. While she continued to receive various teaching offers, she turned them all down. She was once told that teaching would drain her and leave her with little time or energy to paint. Hill clearly devoted herself to her painting and her hard work paid off. In 1974, the Five Civilized Tribes Museum named her a Master Artist, making her the first woman to achieve this honor.

By 2001, Hill had accumulated more than 270 awards, making her the most recognized female Native American artist in the United States. Among some of her highest honors are the Philbrook Art Center’s Waite Phillips Special Artist Trophy for lifetime achievement, being named among the Smithsonian Institute’s People of the Century, and the Academia Italia’s (Cremona) Oscar D’Italia Award. Hill also served on the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women in 1990 and on the U.S. Indian Arts and Crafts Board in 2001.

Joan Hill, Moon Of The Pheasant Dance, 1975, The Wigwam Gallery, Oklahoma City, OK, USA.

Today Joan Hill is still recognized as a painter who beautifully and truthfully depicted her heritage. Her paintings honor her ancestors and serve as visual reminders of a rapidly fading style of traditional Native American art. Her paintings are mostly held in public collections, including several of the most prestigious collections in the United States. Among the institutions that conserve her work are: the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, the National Museum of the American Indian, the Smithsonian Institute in New York, the George Gustav Heye Center, and the Philbrook Museum of Art.

In her artist statement, she said:

All of my work, whether traditional or contemporary, owes a debt to my Creek-Cherokee heritage for the teachings of my beloved parents and grandparents give a base or sustenance to my work. I was also taught to have a deep, spiritual faith in God, a love and respect for the land, nature, the elements and the powers of creation, with a feeling for the eternal and the monumental. Consequently, I am inexorably drawn to the beauty, illusion and mystery of Native American legends and history, which serve as inspiration for the images I use to create a world, not as it is “seen,” but as it is “felt”…

During her lifetime, Hill was able to travel to numerous countries and learn about their own cultures. However, she always maintained a home on her family’s land in Oklahoma until her death in June 2020.

Joan Hill, Council of the Confederacy. Pinterest.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!