The National Gallery in London: Where to Start?

Having lived in London for the past three years as an art lover, I have had more than my fair share of questions about where to “start” at the...

Sophie Pell 3 February 2025

12 January 2022 min Read

John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal opened at The Morgan Library & Museum in New York in October 2019. It was the first-ever museum exhibition to focus exclusively on Sargent’s charcoal portrait drawings. It was a terrific show that made me admire Sargent even more than I did before.

Art lovers know Italian-born American artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) for his gorgeous, large-scale portraits of American and European elites such as Madame X, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, and Lady Agnew of Locknaw. He also painted many beautiful watercolors. Oil portraits made Sargent’s career, and he’s still famous for them today. However, in 1907, he decided that he’d had enough of the demanding job of painting the rich and famous, and he abruptly stopped taking portrait commissions.

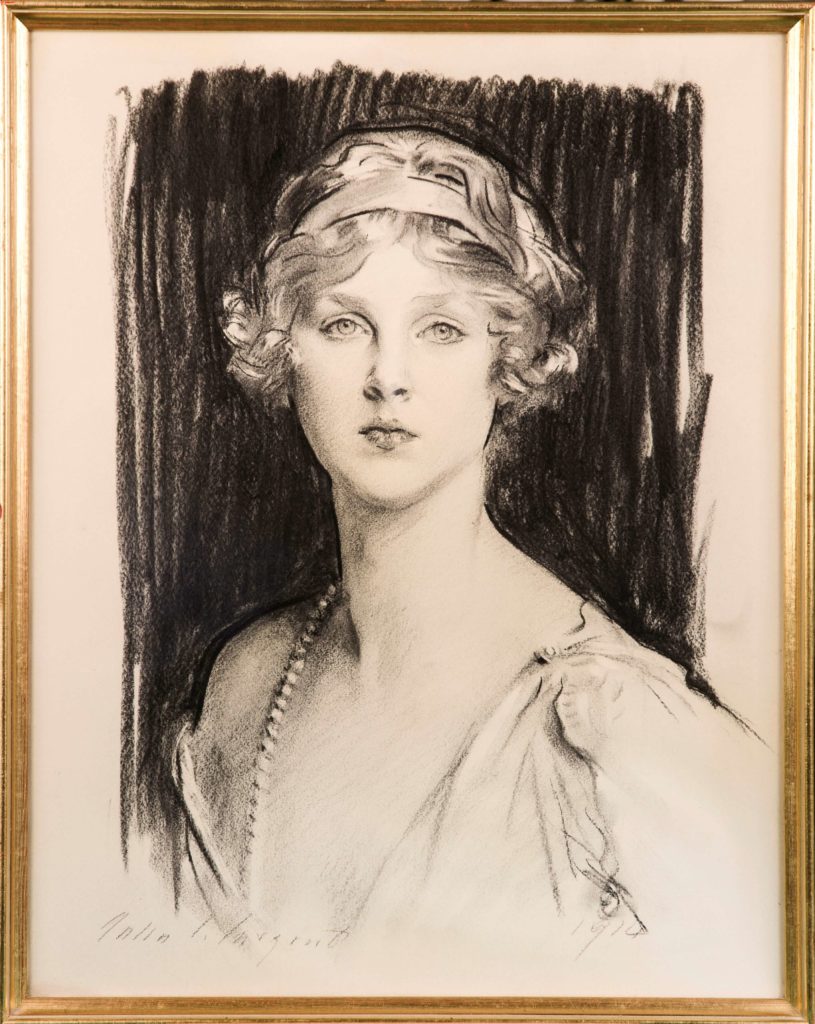

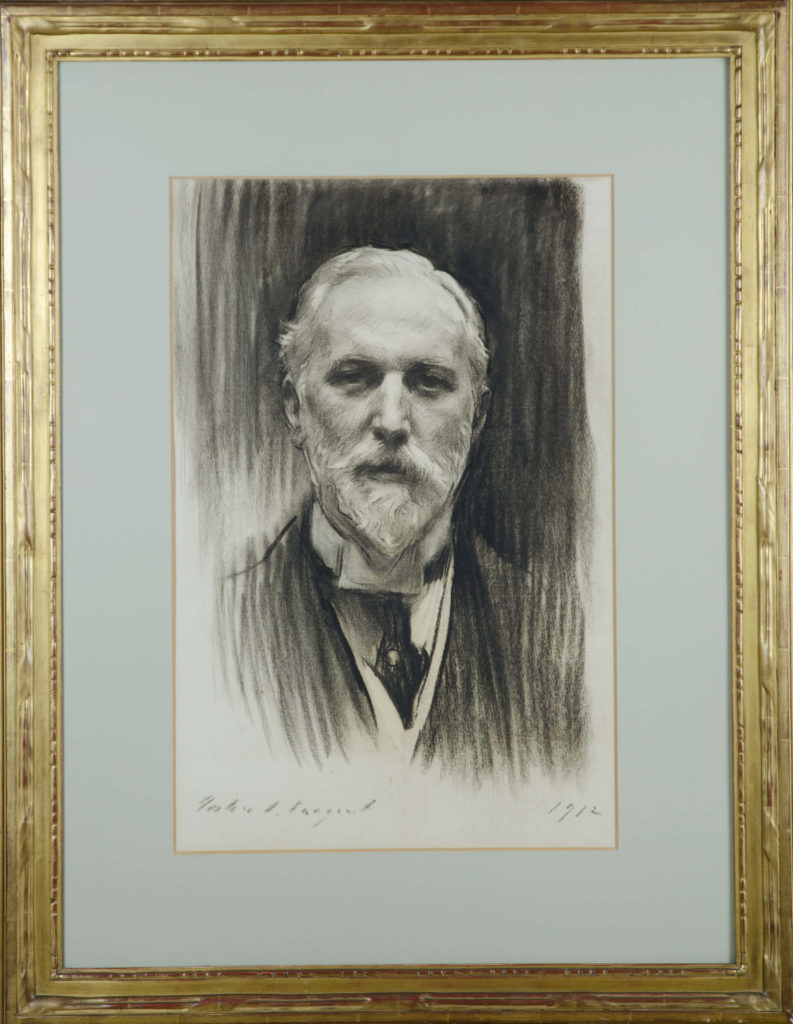

Or at least he tried to. Sargent had become a sought-after portrait painter, and potential customers wouldn’t take no for an answer. So, Sargent came up with a solution to satisfy everyone – charcoal portrait drawings. Such drawings were quicker and easier to create; one took only about three hours to complete instead of the thirteen or more hours necessary for an oil portrait. They are smaller and simpler than oil portraits, but still relatively large and full of Sargent’s characteristic vitality. Sargent made over 750 charcoal portraits in his career. Many were commissions, while others were done as gifts to the sitters.

John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal was curated by Sargent expert Richard Ormond, who is also the artist’s grand-nephew. The show included about 50 works from public and private collections in England and America. They depict men and women from late teens or early 20s through old age. Sitters include aristocrats, artists, writers, performers, politicians, and social luminaries. Most belonged to Sargent’s large social circle, and many were his friends.

Some portraits, like those of Winston Churchill, Henry James, and William Butler Yeats, were immediately recognizable by name or by face. The portrait of American actress Ethel Barrymore was an audience favorite. However, I most enjoyed some of the unfamiliar sitters. My favorite was a lively portrait of composer Ethel Smyth with her mouth open in mid-song. Each Sargent portrait is unique, though impossible to mistake for the work of any other artist. I suspect that every visitor to this exhibition had no trouble coming up with a few favorites.

Sargent’s charcoal portraits are generously sized. They’re smaller than his oil portraits, but they’re certainly not tiny sketches. Most show the sitter’s head and shoulders against a plain background of either bare white paper or dark charcoal. These light and dark backgrounds produce very different effects, and a few darkly-rendered figures on dark backgrounds are particularly spectacular.

Sargent’s charcoal portraits have the same delicate balance of detail and simplification that’s so compelling in his oil paintings. Faces – the most important part of any portrait – are always tightly rendered. Many works highlight fabulous hats, dramatic shawls, and sweeping hairstyles, while the rest of the body and clothing dissolve into the background.

Before visiting the exhibition, I wondered what to expect from Sargent’s charcoal portraits. Since he is celebrated for his bold brushwork and gorgeous colors, I was curious about how effective his greyscale portraits would be. I was delighted, but not surprised, to find that everything great about John Singer Sargent seems extra-concentrated in his charcoal drawings. Without color, I found my attention more fully drawn to Sargent’s unique ability to infuse life and personality into every portrait. In fact, I’m starting to think that Sargent might have been at his most brilliant in his charcoal drawings.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!